|

How the convocation and

arrest of the Acadians succeeded in other places.—A few vessels arrive

at Grand Pre.—Winslow decides to put all young men on board—They resist

but finally obey. —Scenes of woe and distress—Correspondence between

Murray, Winslow and Prebble showing their state of mind—Seven more

vessels arrive four weeks later—Departure of the fleet on the 31st of

October—Other incidents—Computations about the cattle of the Acadians.

I now go back to Grand

I’r<S and other Acadian settlements to resume my narrative in connection

with the proceedings to carry out the deportation. Whether it was that

the details had not been conceived and executed with so much skill, or

that the people were more suspicious, the success of the conspiracy in

the other places was not so remarkable as at. Grand Pr<5. Handheld

complained to Winslow that several families had taken refuge in the

woods: there had even been resistance and some men had been killed.

At Beausjour, where

Monckton was commandant, the failure was more striking. The proclamation

which convoked all the inhabitants, was generally disobeyed; and

Monckton could get together on his transports only about twelve hundred

persons. This was about one third of the population. Major Frye, whom he

had sent to the settlements of Cliipody, Peticodiac and Memrancook, with

orders to bum all the houses and carry off with him the women and

children, could execute only the first part of his instructions. At his

approach, the entire population, having learnt the fate of those who had

obeyed the proclamation, bad fled to the woods. After burning 120 houses

at Chipody, the church included, he entered the Peticodiac River and

ascended it some distance, burning all the buildings on both sides of

the stream. Reaching the principal village, he cast anchor and ordered

Captain Adams, with sixty men, to join the detachments of Lieutenants

Endicott and Billings, which were inarching up the river along its

banks. “Two hundred and fifty houses,” says Haliburton, “were on fire at

one time, in which a great quantity of wheat and flax were consumed. The

miserable inhabitants beheld, from the adjoining woods, the destruction

of their buildings and household goods with horror and dismay; nor did

they venture to offer any resistance, until the wanton attempt was made

to burn their chapel. This they considered as adding insult to injury,

and rushing upon the party, who were too intent on the execution of

their orders to observe the necessary precautions to prevent a surprise,

they killed and wounded twenty-nine rank and file, and then retreated

again to the cover of the forest.”

Major Frye, feeling

unable to do any more, withdrew, carrying off with him twenty-five

infirm or invalid women found in the houses that were burned.

Abbe Le Guerne, who was

in the neighborhood of Beausejour before and after the deportation,

related these events n detail at the very time in a letter to the

commandant of Louisburg.

“After the taking of

Beausejour,” says he, “I thought I perceived that the officers of the

Fort were hiding sinister designs, while seeming to be interested in

improving the settlements. An order came that all should go to the Fort,

to make arrangements, it was said, about the lands. I felt tempted to

advise disobedience to this order which, to my mind, boded ill; but,

apart from the fact that I had promised the authorities not to meddle in

temporal affairs, I feared that the Acadians would not listen to me. For

they regarded the English as their masters; they thought themselves

secure under the solemn pledge of the capitulation; they thought

themselves bound to obedience. For these reasons I could not. dissuade

them therefrom without running the risk of bearing the responsibility of

all the misfortunes that have befallen them, for this disobedience of

some would have been a specious and solitary pretext for severity

against all.

“As soon as those that

went to the Fort were made prisoners, I saw clearly that concessions

became useless. The English commandant, by his tempting promises, by

captious offers, and even by presents, thought he had won me over to his

interest. Thinking himself sure of me, he sent me word that he wished to

see me. I took good care not to fall into the snare he had got ready for

me; 1 replied that I did not mistrust him, but that he might receive

orders against the missionaries, which he would be obliged to execute

against me, and, since he was ordered to deport the Acadians, the only

course left for me to adopt was to withdraw; but that 1 should gladly

remain if he received contrary orders. To a letter in which he urged me

again to banish all distrust, I answered that Mr. Maillard had been put

on board ship in spite of the positive assurance of a governor, and that

I deemed it better to withdraw than to expose myself in any way.”

Murray, at Pigiguit,

fulfilled his task with a success fairly equal to that of Winslow at

Grand Pre. The inhabitants did not submit to the proclamation with the

same unanimity; yet they all finally yielded without making any

resistance. On the very evening of the convocation, lie thus reported

his success to Winslow:

“I have succeeded

finely, and have got one hundred and eighty-three men in my possession.

I believe there are but very few left, except their sick. I am hopeful

yon have had equally as good luck; should be glad you would send me

Transports as soon as possible. I should also esteem it a favor, if you

could also send me an officer and thirty men more, as I shall be obliged

to send to some distant rivers, where they are not all come yet.”

The day after the

arrest, the prisoners of Grand Pr6 begged Winslow to allow a certain

number of them to visit their families in order to acquaint them with

what had occurred and to console them. After consulting with his

officers, Winslow consented to let twenty prisoners, of whom ten were

from Riviere aux Canards and ten from Grand Pro, go every day, by turns,

to visit their families, on condition that the others be responsible for

their return.

Patrols scoured the

country in every direction to seize on such as had not responded to the

call. With the exception of some who were killed while trying to run

away, and of some others who succeeded in escaping, all those who had

held back gave themselves up as prisoners. In a few days the number of

prisoners was over five hundred.

Winslow's Journal

contains a petition that was addressed to him by the captives a few days

after their arrest. It is eloquent in its simplicity, touching by the

sentiments it expresses. Strong as was their attachment to their

property, to their country; great as were their woes and griefs, what

they were most anxious about was their spiritual welfare. In this

overwhelming disaster, when it would seem that nature stifles every

feeling except the sense of present evil, the last and only favor they

begged of their tormentors, who refused it, referred to their religious

interests.

“At the sight,” wrote

they, “of the evils that seem to threaten us on every side, we are

obliged to implore your protection and to beg of you to intercede with

His Majesty, that he may have a care for those amongst us who have

inviolably kept the fidelity and submission promised to His Majesty ;

and, as you have given us to understand that the King lias ordered us to

be transported out of this Province, we beg of you that, if we must

forsake our lands, we may at least be allowed to go to places where we

shall find fellow-countrymen, all expenses being defrayed by ourselves;

and that we may be granted a suitable length of time therefor; and all

the more because, by this means, we shall be able to preserve our

religion, which we have deeply at heart, and for which we are content to

sacrifice our property.”

Did Winslow understand

the sublimity of the sentiments expressed in this petition ? His Journal

does not tell us. He moves on without a word of comment.' He was engaged

upon a job that allowed him neither to turn back nor to open his heart

to pity. He had orders to arrest the men and lads above ten years, to

put them on board the ships and to send them away. He had successfully

performed the first part of his task; there now remained the

embarkation, which was to be the greatest wrench of all. Lawrence’s

pitiless edict willed it so; everything must be sacrificed to ensure the

safe accomplishment of his plan.

As indignation was

openly expressed at his hardheartedness, he took advantage of the

arrival of five vessels to proceed immediately with the embarkation. In

the forenoon of September 10th, he sent word to the prisoners by Pere

Landry, who acted as interpreter, that two hundred and fifty of them,

beginning by the young men. would be put on board ship directly; that

they hud but one hour to get ready, seeing that the tide was on the

point of ebbing. “Landry was extremely surprised,” says Winslow, “but I

told him that the thing must be done, and that I was going to give my

orders.” As I have not; access to Winslow’s Journal, I will let Casgrain

relate the episode of this embarkation.

“The prisoners were

brought before the garrison and drawn up in column, six abreast. Then

the officers ordered all the unmarried men, to the number of a hundred

and fifty-one, to step out of the ranks ; and, after having put these

latter in order of march, they flanked them on all sides with eighty

soldiers of the garrison under command of Captain Adams.

“Up to this moment all

these unfortunate men had submitted without resistance; but, when they

were told to march towards the shore and be there put on board ship,

they protested and refused to obey. It was no use commanding and

threatening them ; all were obstinate in their revolt, with cries and

extreme excitement, saying truly that, by this barbarous measure, sons

were-separated from their fathers, brothers from their brothers. This

was the beginning of that inexcusable dismemberment of families which

has' stained with an indelible blot the name of its authors.

“When one knows that

some of these young people were mere lads from ten to twelve years old,

and therefore much less to he feared than married men in the vigor of

manhood, who had greater interests to protect, it is impossible to

understand this refinement of cruelty.”

Let Winslow himself

relate this part of the incident:

“I ordered ye prisoners

to march. They all answered they would not go without their fathers. I

told them that was a word I did not understand, for that the King’s

command was to me absolute and ' should be absolutely obeyed and that I

did not love harsh means, but that the time did not admit of parlies or

delays, and then ordered the whole troops to fix their bayonets aud

advance towards the Acadians, and bid the 4 right hand files of the

prisoners, consisting of 24 men, which I told off myself to divide from

the rest, one of whom I took hold of who opposed the marching, and bid

march; he obeyed and the rest followed, though slowly, and wTent off

praying, singing, and crying, being met by the women and children all

the way (which is mile) with great lamentations upon their knees,

praying, etc., etc.”

“Another squad,”

Casgrain continues, “composed of a hundred married men, was embarked

directly after the first amid similar scenes. Fathers inquired of their

wives on the shore where their sons were, brothers asked about their

brothers, who had just been led into the ships; and they begged the

officers to put them together. By way of answer the soldiers thrust

their bayonets forward and pushed the captives into the boats.”

Two days before this

lirst embarkation Murray wrote to Winslow:

“I received your favor,

and am extremely pleased that things are so clever at Grand Pre, and

thaf the poor devils are so resigned; here they are more patient than I

could have expected for persons so circumstanced, and, what still

surprises me, quite unconcerned. When I think of those at Annapolis, I

appear over thoughtful of summoning them in; I am afraid there will be

some difficulty in getting them together ; you know our soldiers hate

them, and if they can but find a pretext to kill them they will. I am

really glad to think your camp is so well secured—as the French said, at

least a good prison for inhabitants. I long much to see the poor

wretches embarked, and our affairs a little settled, and then I will do

myself the pleasure of meeting you and drinking their good voyage."

The vessels that were

to bring provisions and transport the captives were very late in

arriving. Murray and Winslow were getting impatient; the pressing

letters written by the latter to the Commissary, Saul, remained

unanswered. After <i long delay a ship laden with provisions appeared

before Grand Pr6: but the transports for the Acadians and the ships that

were to convoy them did not come till much later. Winslow, writing to a

friend at Halifax, thus describes his impressions: “I know they deserve

all and more than they feel; yet, it hurts me to hear their weepings and

wailings and gnashing of teeth. I am in hopes our affairs will soon put

on another face, and we get transports, and I rid of the worst piece of

service that ever I was in.”

At last, after four

interminable weeks, seven vessels hove in sight, three of which were

sent to Murray, who could not contain his joy: “Thank God! ” says he,

“the transports are come at last. So soon as I have shipped oil my

rascals, I will come down and settle matters with you, and enjoy

ourselves a little".

In fairness to Winslow

I choose in preference those parts of his Journal which exhibit him in

the most favorable light. Where facts that are positively horrible fill

so large a space, one eagerly greets a semblance of humane feelings.

These are so rare that one need not be squeamish. Such as they are,

however, they refresh the soul and cheer the sight like a green oasis

after the burning sands of the desert. One longs for them as the diver

rising to the surface longs for a breath of air. Nevertheless it is

expedient to show what a vile fellow was that Murray who, for many years

past, had been in charge of this district, the most populous in Acadia.

His letters invariably end with a fervent wish to drink and make merry.

Prebble, at least, though he never forgets the enjoyment he hopes to

secure, “ the good things of this world,” does not forget spiritual

things either, albeit he makes them a text for mockery of the Acadians’

belief. Murray’s mind grovels in gross pleasures alone. He is always

thirsty; he is always ready to start the nunc est bihendum, and this

thought haunts him ever. Such is the man after his own heart whom

Lawrence chose to rule and exasperate this people, to prepare and

execute the dark designs he had long been meditating. Think how the

oppression of such a sensualist must have weighed on the Acadians, and

then wonder at their unvaryingly peaceful submission to the caprices of

this despot.

Winslow prepared

everything for the embarkation and gave notice to the prisoners to be

ready for October 8th: “Even after this warning,” says he, “I could not

persuade them I was in earnest.”

I cannot attempt to

describe the scenes that marked the embarking of the rest of the people.

Winslow thus reports them in his Journal: “Began to embark the

inhabitants, who went off very solentarily (sic) and unwillingly ; the

women in great distress, carrying off their children in their arms;

others carrying their decrepit parents in their carts with all their

goods, moving in great confusion, and appeared a scene of woe and

distress.”

The four vessels with

their human cargo lingered in the roadstead until the 29tli of the same

month (October). Meanwhile there remained yet upon the shore more than

half the population who had not been able to find place on board.

Some were still hiding

in the woods. In order to force them to surrender, Winslow issued the

following order, which needs no comment: “If within-days the absent ones

were not delivered up, military execution would be immediately visited

upon the next of kin.”

“In short,” says

Haliburton, “so operative were the terrors that surrounded them, that,

of twenty-four young men who deserted from a Transport, twenty-two were

glad to return of themselves, the others being shot by sentinels; and

one of their friends, Francois Hubert, believed to have been an

accessory to their escape, was carried on shore to behold the

destruction of his house and effects, which were burned in his presence,

as a punishment for his temerity and his perfidious aid to his

comrades.”

We have no written

proof that acts of cruelty other than those necessitated by the very

nature of the enterprise were committed by the soldiers ; but, when we

take into account Lawrence’s instructions “to distress them as much as

possible,” and the hatred entertained against everything French and

Catholic, when the soldiers had about full scope to act as they pleased,

the experience of history is there to prove that there must have

occurred scenes of cruelty more revolting than those which have been

chronicled in Winslow’s Journal.

It must have been to

put an end to abuses of this sort that he ordered the soldiers and

sailors, under pain of severe chastisements, not to absent themselves

any more without leave from their quarters, “that an end may be put to

distressing this distressed people.”

Haliburton has supposed

that the first vessels which received on October 10th their shipment of

young and married men, were sent off directly. This was, indeed

according to Lawrence’s orders; but, for want of provisions, and perhaps

also because it was thought more prudent to have the vessels accompanied

by convoys, they did not set sail till the bulk of the fleet did, at the

end of October. Parkman has rightly pointed out this mistake, which

tended to demonstrate that the separation of families was general and

intentional. True, this evil intention can be demonstrated, whatever may

be the time at which the ships set sail: for I have reason to believe

that the prisoners remained exactly as they were distributed on board

the ships on the 10th of October and that no change was made between

that date and the departure. I will give, further on, some instances

referring to members of my own family, which seem to settle the

question. However, I wish to correct Haliburton’s mistake and to give

the reader an opportunity of doubting, if he thinks he honestly can, the

correctness of my opinion. There are enough, horrors m this story

without exaggerating the reality.

In Winslow’s

instructions as to the destination of the Acadians of the Mines

District, we read:

To North Carolina, so

many.

To Virginia id.

To Maryland such a

number of vessels as will transport 500 per-pons, or in proportion, if

the number to be shipped off should exceed 2,000.

Now, the total number,

from Pigiguit and Grand Pro, exceeded 3,000, and perhaps 3,600. Other

vessels followed the first, and the embarkation took place as they

arrived, amid the same scenes of desolation and despair. Then, on

October 29th, the fleet set sail.

All that vast bay,

around which but lately an industrious people worked like a swarm of

bees, was now deserted. In the silent villages, where the doors swung

idly in the wind, nothing was heard but the tramp of soldiery and the

lowing of cattle wandering anxiously around the stables as if looking

for their masters.

Lawrence’s orders were

that all buildings be destroyed. The last ships that carried off the

exiles had not yet passed the entrance to the Mines Basin, when these

poor people, casting a farewell glance on their dear native land,

perceived clouds of smoke rising from their own roofs. In a few moments

all the shore, from Cape Blomedon to Gaspereau was in flames. This was

truly an eternal farewell, the utter annihilation of whatever illusions

might still have haunted their minds.2

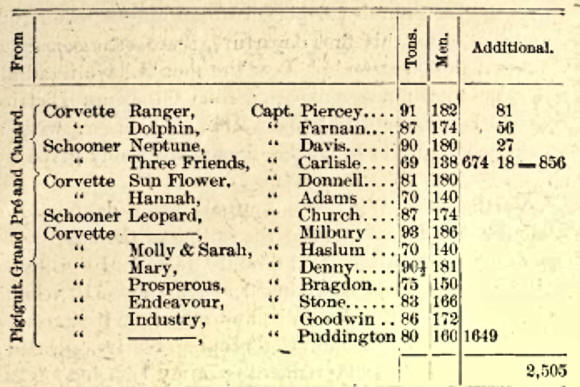

The convoys of the

fleet were : the Nightingale, Captain Diggs; the Snow (Halifax), Captain

Taggert; the armed schooner, JVarron, Captain Adams, with the following

transports:—

that the total number

deported from Pigiguit was 1,100, and that, after this first departure,

there still remained more than 600 at Grand Pre, we should have to admit

that the total number deported from the Hines District would be nearer

4,000 than 2,921, which is, with a variation of units only, the figure

invariably given by historians.

Furthermore, Winslow’s

Journal, under date of November 3rd, four days after the sailing of the

fleet, gives the number deported from Grand Pr<5 as 1,510 in 9 vessels;

whereas the list produced above shows 10 vessels instead of 9. Besides,

Winslow adds: “ I put more than two to a ton, and the people greatly

crowded; there is more than 600 remaining i:i my District.”

If this figure, 1,510,

is correct, then there would not be quite two persons to a ton.

It is not easy to

account for these discrepancies; still, as we know, from a memorial of

Abbe de l’lsle-Dieu, that the population of Mines Basin was, two years

before, about 4,500, we may, with more likelihood, I think, estimate the

total number deported from this district as between 3,600, and 4,000,

and very likely nearer the former than the latter figure. The remainder

must either have quitted the country during Lawrence’s administration,

or have run away at the time of the deportation.

According to Winslow’s

Journal, Murray completed his task about the end of October, having sent

off 1.100 persons “in four frightfully crowded Transports." This is

strikingly at variance with Bulkeley’s estimate, which gives the number

contained in these four vessels as 674, and with my correction raising

it to 856. There would still be at least 244 persons to be accounted

for, so as to equal Winslow’s eleven hundred. I am inclined to think

that, after the sailing of his four1 ships, Murray decided to add his

prisoners to the shipment from Grand Pie. The two places were near each

other; the departure of so many people had made the doubling of

garrisons useless; and it was now more convenient to operate from one

point. This would explain how it happened that his task was ended, when

we know for a certainty that he still had between two and three hundred

prisoners to dispose of. Murray was gasping with thirst; he was burning

with desire to join Winslow and enjoy himself.

Though Winslow and

Bulkeley’s reports do not agree in the details, they do in the total of

the first departure, which they state, respectively, as 2,921 and 2,923.

Winslow says he still had 600 to deport; Bulkeley declares he knows

nothing of the number embarked later on. The only doubtful point

apparently is, whether or not the 600 still with Winslow comprised the

244 needed to complete Murray’s 1,100. Winslow’s task was not done till

December 20th, when two vessels laden with 232 persons carried off the

remnant of the population.

The total of deported

persons at Annapolis, generally estimated at 1,654, seems to agree with

what we know of the total population minus the number of those who

escaped the deportation. At Cobequid (Truro) the people had been alarmed

in time and had taken refuge in Prince Edward Island.

We have seen how, at

Chipody and Peticodiac, Major Frye had been able only to burn the houses

and arrest a few women. In: the district of Beaubassin those who fell

into the hands of the authorities were the inhabitants who dwelt in the

immediate neighborhood of Beausejour. Monckton vaguely estimates their

number at more than a thousand. This district contained at least 4,000

souls. The total number of Acadians deported at this time may be put

down as, at least, 6,500 and, at the utmost, 7,500. We shall see later

that this number was ultimately doubled, and that the deportations did

not cease till after the peace of 1763.

Six hundred and

eighty-six buildings, not including eleven mills and two churches, were

burned at Grand Pre and at Riviere aux Canards. The families carried off

from these two parishes owned, according to Winslow’s estimate, 7,833

head of cattleyj493 horses, 8,690 sheep and 4,197 pigs. The total amount

of live stock owned by the Acadians at the time of the deportation has

been variously estimated by different historians, or, to speak more

correctly, very few have paid any attention to this subject. Raynal, who

cannot be considered a safe guide in this matter, goes as high as

200,000. This figure is altogether too large. Rameau, who has made a

much deeper study than any other historian of the domestic history of

the Acadians, sets the total at 130,000, comprising horned cattle,

horses, sheep and pigs. Whoever will take the trouble to follow this

author in tlie patient researches to which he has devoted himself for

nearly forty years, cannot help assigning to his opinion on these

statistical questions considerable authority. Leaving out of our

calculation the few thousand Acadians who then lived in Prince Edward

Island, there were, in the Peninsula and in the Beaubassin district,

about 13,000 souls. Now, taking Winslow’s figures, both for the

population and the live stock at Grand Prd, and applying the same

proportion to the entire population of Acadia, we get the following

result:

2,300 inhabitants at

Grand Pre owned—

Horned cattle 7,838

Sheep 8,690

Pigs 4,197

Horses 493

21,213

Therefore, we may not

unreasonably suppose, taking as a basis Winslow’s estimate at Grand Pr6,

that the Acadians residing in English territory at the time of the

deportation, viz. :

13,000 inhabitants,

owned—

Horned cattle 43,500

Sheep 48,500

Pigs 23,500

Horses 2,800

118,300

Rosalie Boure (Bourg),

my great-grandmother, wife of Jean Le Prince and mother of Jean Charles

Prince, bishop of St. Hyacinthe, P. Q., was then five years old. The

impression caused' by the burning of their habitations, when the fleet

was going out of the Basin remained always vivid in her mind. She died

in 1846 at the age of ninety-six. An oil portrait of her is in my

possession.

This report, as well as

those of other places, had disappeared from the Archives at the time

when Dr. Brown was writing; this one was given him by the Secretary of

the Council under Lawrence, Richard Bulkeley, who was still living in

1790. At the bottom of his report he adds :

“N. B. I have made some

blunder by the loss of the principal list of those who embarked, but the

number of souls that embarked on board the Transports were 2,921. How

many embarked afterwards I know not. The remainder of the Neutrals

remained until more Transports arrived.”

By some researches I

have succeeded in rectifying the list furnished by Bulkeley, with regard

to the vessels that sailed from Pigiguit. I have added 182 for this

place; my additions are to be found in the extreme right hand column of

the list. To equal Bulkeley’s total, 416 would have also to be added for

Grand Pre But, as, on the other hand, we know from Winslow’s Journal. |