|

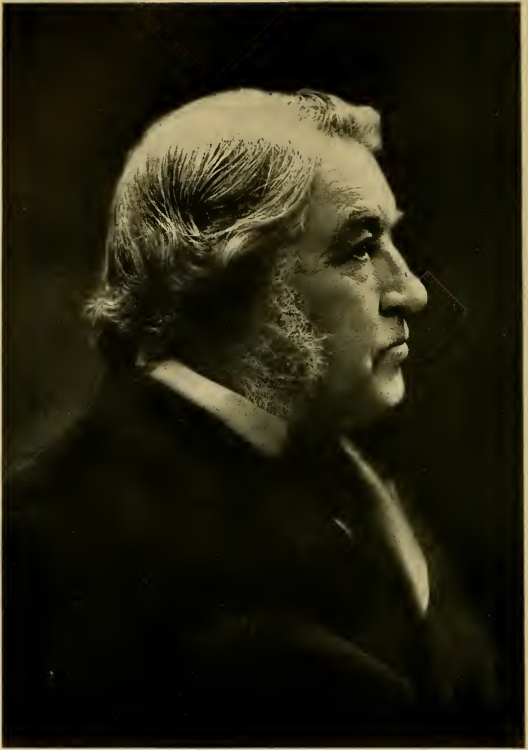

(1821-1915)

SIR CHARLES TUPPER was

a statesman of vision and a party general of audacity. His name recalls

thunder on the hustings, strength to wavering Cabinet Ministers, and a

will to see-it-through in any cause he undertook. He initiated and

carried Confederation in a rebellious Nova Scotia, he promoted the

National Policy in the Dominion, he fathered and defended the Canadian

Pacific Railway through perilous years of obstruction. No Canadian

politician has had more hard, disagreeable tasks, but to each he brought

a dashing courage which usually swept all before it. For fifty years he

was a storm-centre in politics, and no matter how threatening the gale,

he braced his feet, like a fisherman bound for the Grand Banks, and

faced the danger without flinching. No speaker could still him, no

audience terrify this veteran of a hundred battles. Now he used a stream

of invective, again he tripped an enemy with fox-like cunning. He lived

and thrived in an age of strong words. Nova Scotians were wearying of

ornate orators, and his energy and bluster were as invigorating as a

northwest wind. His deadly earnestness carried weight, his fighting

manner roused friends and cowed his more meek opponents.

“I have been defeated by the future leader of the Conservative party,”

said Joseph Howe in 1855, when the young country doctor carried

Cumberland for the Assembly. From then until his death, sixty years

later, Charles Tupper was never long from sight. Conservatives linked

him with Macdonald for his capacity and his achievements. Liberals hated

and denounced him for his egotism and his political methods, but they

never ignored him. As party feeling subsides, his foresight and

resolution, his devotion to national and Imperial causes, win praise

from every party.

“In my judgment,” said Sir Wilfrid Laurier in 1916, “the chief

characteristic of Tupper was courage; courage which no obstacle could

down, which rushed to the assault, and which, if repulsed, came back to

the combat again and again; courage which battered and hammered, perhaps

not always judiciously, but always effectively; courage which never

admitted defeat, and which in the midst of overwhelming disaster ever

maintained the proud carriage of unconquerable defiance.”

J. A. Macdonald and Charles Tupper first met at the Confederation

Conferences in 1864. They became firm friends, and until the former’s

death constantly co-operated and supplemented each other. When Nova

Scotia refused the Quebec resolutions it was Tupper’s duty to win over

his Province. It was a three years’ task, but he never hesitated. When

the Macdonald Government staggered under the Pacific Scandal charges in

1873, Tupper rushed to the defence in a lengthy speech, and persuaded

Macdonald not to resign the leadership. In 1880 he joined in negotiating

the Canadian Pacific contract, and when its prodigality was attacked he

was its most unreserved defender. In December, 1883, Sir John cabled Sir

Charles, who was then in London: “Pacific in trouble: you should be

here.” Next morning came the reply: “Sailing on Thursday.” In 1886 Sir

John heard unfavorable news of the political outlook in Nova Scotia, and

wrote: “I cannot too strongly urge upon you the absolute necessity of

your coming out at once, and do not like to contemplate the evil

consequences of your failing to do so.” Sir John’s last Macedonian cry

was in January, 1891, when he cabled: “Your presence during election

contest in Maritime Provinces essential to encourage our friends. Please

come. Answer.” The war horse promptly responded, and in a few days

“walked down the gangplank at New York with his usual springy step.”

“After me the deluge,” Sir John Macdonald had said, and despite a

pervading feeling for years that at his death Tupper would take the

leadership, this was not the case. His hour came in the crisis of his

party in 1896, when the Orangemen rose against the Remedial Bill of Sir

Mackenzie Bowell’s Government, for the benefit of the Roman Catholics of

Manitoba. Tupper, summoned from England to take the Premiership at

seventy-five, dashed into the fray like a regiment of cavalry. He faced

a frightened Cabinet just recovering from wholesale resignations, and

met storms of “boos” from audiences of once subservient Conservatives.

In Toronto, he fought for hours with a turbulent crowd who refused a

hearing in that party stronghold. The Government was defeated by the

Liberals under Wilfrid Laurier. Tupper lingered four years as Opposition

leader, when, after another defeat, he sought the repose he had well

earned.

It is significant that a political career so marked by stress should

have begun in storm. Most of us can recall some red-headed boy who was

always in a fight if there was one. Charles Tupper had a genius for

either finding or making a political squabble. In March, 1852, he

entered the campaign in Cumberland in support of T. A. De Wolfe. His

first speech, at a little rural meeting, was so impressive that he was

persuaded to make De Wolfe’s nomination speech the next day. Here a

dispute took place as to who should speak first, the nominators or the

candidates. An unseemly row followed, lasting for an hour, in which

young Tupper took his full part. Joseph Howe was one of the opposing

candidates, and the warfare which then began lasted for nearly twenty

years.

It is a matter of surprise that when Tupper entered the political arena,

and for twenty years afterwards, he was exceedingly nervous before

rising to speak, though his timidity soon left him once he was on his

feet. “I did not sleep much that night,” he wrote of the hours preceding

that first nomination speech, “and was so nervous the next morning that

I threw up my breakfast on the way to the corner where the nomination

was to take place.”

Tupper and Howe had met just previously under peculiar circumstances.

Dr. George Johnson, afterwards Dominion Statistician, related in the

Halifax Herald in 1909 that the future rivals both happened in his

father’s house one night. When nine o’clock arrived the elder Johnson,

as was his custom, conducted family worship. The visitors knelt with the

household and heard the devout host invoke “the blessing of heaven upon

the two strangers within the gate, and ask that they might be animated

with a strong sense of duty in their public life.”

Tupper at this time was a busy and prosperous country doctor, with a

decided aptitude for politics. He had been born in Amherst, July 2,

1821, of Puritan stock which emigrated from England to America in 1635,

and from Connecticut to Cornwallis, N.S., in 1763, taking possession of

land vacated by Acadians expelled in 1755. Charles was a precocious

youth, and relates of his own childhood: “I do not remember when I

commenced the study of Latin, but when I was seven years old I had read

the whole Bible aloud to my father.” He had the same self-confidence and

pugnacity that marked his later years, and in his journal describes a

combat with the mate of a schooner who smoked to the windward of the

youth. The mate was laid up for three days.

Young Tupper’s medical education in Edinburgh was thorough, and he was

soon firmly established as a local practitioner. “In person,” says

Edward Manning Saunders, “he was of medium height, straight, muscular,

wiry and had intense nervous energy, which gave him quickness of

movement and ceaseless mental activity. ... In his sleigh, carriage or

saddle, he went from place to place, sometimes in deep and drifted snow,

and at other times in mud more difficult than the worst snow drifts. In

twelve years of practice before he was called into the sphere of

politics, mountainous obstacles became a level plain and toil and

exposure the highest enjoyment.”

Fortune decreed that the practice of medicine, for which the young

doctor was so well fitted, was to play a small part in his life. After

1855 he was in politics to stay, and save a few years in Toronto, when

in Opposition in the ’seventies, he gave little time to his profession.

Tupper’s rise in Nova Scotia politics was of that rapid character that

marks a strong personality of a fresh cast of mind. His defeat of Howe

in Cumberland in 1855 astounded the Province, and cast the first shadow

over the future of that popular idol, the man whom Sir Wilfrid Laurier

has described as “the most potent influence in Nova Scotia, and perhaps

the brightest impersonation of intellect that ever adorned the halls of

the Canadian Legislature.” The Conservative leader, J. W. Johnstone,!

was advancing in years and wished to retire. He was ready to give Tupper

his post, but to this the young doctor would not listen. They

compromised by Johnstone remaining leader and Tupper doing most of the

work. In his first session at Halifax in 1856, Tupper spoke out boldly

and declared:

“I did not come here to play the game of follow my leader. I did not

come here the representative of any particular party, bound to vote

contrary to my own convictions, but to perform honestly and fearlessly,

to the best of my ability, my duty to my country.”

In his first month in the Assembly the Opposition strength rose from 15

to 22. Thenceforward he was in the muddy stream of Nova Scotia

politics,- with its perplexing local issues, until the Confederation

movement loomed up, largely at his own bidding, to overshadow all other

topics. From this party’s defeat in 1859 to their return to office in

1863 Tupper maintained a running fire of attack on the Government. On

his return to office he introduced and passed in 1864 a measure of

permanent value, providing for compulsory education in Nova Scotia.

Confederation was too large and complicated a movement to be the

creation of any one man. It was the result of a combination of men and

circumstances. In its accomplishment, Tupper ranks with Brown, Macdonald

and Cartier, and in giving it its first concrete impetus he stands

alone. Premier Johnstone of Nova Scotia, with his fellow delegates, had

discussed the subject with Lord Durham at Quebec in 1838. Johnstone had

submitted a scheme for union to the Nova Scotia Assembly in 1854.

Charles Tupper, lecturing at St. John in 1860, had favored a union of

the British North American Provinces, even going so far as to include

the Red River and Saskatchewan country. Tupper’s opportunity for action

came in 1864, when, as Premier of Nova Scotia, he put through the

Assembly a resolution favoring a conference at Charlottetown regarding a

union of the Maritime Provinces, a policy he had also advocated in his

St. John lecture. This was adopted a few weeks before George Brown’s

committee had reported at Quebec in favor of a federative system, either

for Canada or all the colonies. It was followed in August by a visit to

the Maritime Provinces by a party of Canadian legislators, invited by

Dr. Tupper on the suggestion of Sandford Fleming, engineer for the

Intercolonial Railway.

Looking back at this trickling brook of national consciousness, it is

interesting to recall the vision and sense of difficulties felt by so

potent a Father of Confederation.

“I do not rise,” said Tupper, in moving for the Charlottetown

Conference, “for the purpose of bringing before you the subject of the

union of the Maritime Provinces, but rather to propose to you their

reunion.

. . . Whilst I believe that the union of the Maritime Provinces and

Canada, of all British America, under one government would be desirable

if it were practicable—I believe that to be a question which far

transcends in its difficulties .the power of any human advocacy to

accomplish—I am not insensible to the feeling that the time may not be

far distant when events which are far more powerful than any human

advocacy may place British America in a position to render a union into

one compact whole, may not only render 250 -such a union practicable,

but absolutely necessary. I need hardly tell you that contiguous to this

there is a great Power, with whom the prevailing sentiment has long

been—

“‘No pent-up Utica contracts our powers,

For the whole boundless continent is ours.’

This has long been the fundamental principle which has animated the

Republic of America.”

Dr. Tupper then raised a point which had an increasing influence in

solidifying opinion for Confederation, and that was the danger from the

disbanding armies in the United States as the Civil War closed.

“I am satisfied,” he concluded, “that looking to emigration, to the

elevation of public credit, to the elevation of public sentiment which

must arise from enlarging the sphere of action, the interests of these

Provinces require that they should be united under one government and

legislature. It would tend to decrease the personal element in our

political discussions, and to rest the claims of our public men more

upon the advocacy of public questions than it is possible at the present

moment whilst these colonies are so limited in extent.” Canada, too, had

caught the infection of national consciousness and sent her delegates to

the conference at Charlottetown. The air was charged with a feeling of

national change. The Civil War was near its end, the reciprocity treaty

with the United States was unlikely to be renewed, and the British

American Provinces looked toward each other with yearning and

dependence. The Charlottetown Conference adjourned to Quebec to consider

a larger union, pausing on the way for several public meetings. At

Halifax, Tupper, presiding at a banquet to the visiting delegates, said

he was “perhaps safe in saying that no more momentous gathering of

public men has ever taken place in these Provinces.”

The same sense of great impending events marked the utterances at

Quebec. “From the time,” said Dr. Tupper, replying to a toast to the

Nova Scotia delegates, “when the immortal Wolfe decided on the Plains of

Abraham the destiny of British America, to the present, no event has

exceeded in importance or magnitude the one which is now taking place in

this ancient and famous city.”

Going on, he discussed the necessity for Canada to have all year round

access to the sea. “Why is it,” he asked, “that the Intercolonial

Railway is not a fact? It is because, being divided, that which is the

common interest of these colonies has been neglected; and when it is

understood that the construction of the work is going to give Canada

that which is so essential to her, its importance will be understood,

not only in connection with your political greatness, but also in

connection with your commercial interests, as affording increased means

of communication with the Lower Provinces. For the inexhaustible

resources of the great West will flow down the St. Lawrence to Quebec,

and from there to the magnificent harbors of Halifax and St. John, open

at all seasons of the year.”

These were brave prophetic words, but it was not until 1876 that the

Intercolonial was opened. It has since borne avalanches of criticism for

its burden of political place-hunters, its easy-going management, and

its deficits, but it cemented national sentiment, and in the great war

opening in 1914 its usefulness as the only winter outlet for overseas

troops abundantly justified its construction as a national enterprise.

It was an easy matter to agree to the union scheme at Quebec, but the

testing of Tupper and his colleagues came on their return to Nova

Scotia. No torch-light processions awaited them; only sullen politicians

and people, who were soon to be inflamed to the verge of rebellion by

Howe, Annand and others. It was a long, stubborn battle, and its

complete success for union was a matter of years. Tupper was cunning

enough to devote his energies in the Legislature to other topics, and on

union, like Bre’r Fox, he “lay low.” Not until 1866 was there

opportunity to press for a vote. Then, on the defection of William

Miller from the antis, he made bold to move for a conference with the

Imperial authorities on a scheme more favorable to Nova Scotia than that

framed at Quebec. New Brunswick, which had been faltering, came over to

the union cause. Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland had definitely

withdrawn, but Canada joined the two Maritime Provinces in the

Conference in London, when the Confederation Act was drafted. Tupper was

one of the delegates, but he returned to find opposition to union

unabated among the people.

The campaign in the summer of 1867 was marked on June 4 by a historic

joint debate at Truro between Howe and Tupper. Their utterances were

recorded in shorthand by arrangement, and the record of this battle of

giants recalls the great Lincoln-Douglas debate across the border a few

years earlier. Howe and Tupper spoke at length, and crystalized the

arguments on both sides. Howe, speaking first, engaged in good-natured

banter, and though he may have pleased his hearers, his words were not

strong, as a set of arguments for his side. He was on his defence for

his own advocacy of union, but with a light hand he brushed this aside:

“A man might discuss the question whether he would marry a girl or not,

but that would not subject him to an action for breach of promise if he

had never actually promised to marry her.”

Tupper was more serious and more logical. He met his opponent largely by

quoting Howe’s earlier declarations. He illuminated his rival’s

opposition to Confederation when he said:

“Mr. Howe is possessed of an eloquence second to no man, but it is his

misfortune that he can follow nobody, however wise or judicious a

measure may be. He cannot give his assistance to any great question

unless he is at the head promoting it. Day after day he had pledged

himself not only to the principles but to the details of union; but when

he saw it was to be accomplished by his opponents, he is found in the

foremost ranks of its opponents.”

Confederation Day came, even in Nova Scotia, and there, despite the

opposition of the majority of the people, such a motto as this appeared

in a window of St. Mary’s Globe House: “Yesterday a provincial town;

to-day a continental city.” Sir John A. Macdonald had announced his

Cabinet, after a most trying experience in reconciling all Provinces and

races, and almost giving up and advising that George Brown be called on.

Dr. Tupper was not in the Cabinet, and he made his own explanation that

day in Halifax:

“In order to form a strong union Government, combining the Reformers and

Conservatives of Ontario, the Catholics and Protestants of Quebec, and

the Liberals and Conservatives of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, my

friend, Mr. McGee, and I requested that the Hon. Edward Kenny, the

President of the Legislative Council, should be substituted in our

stead, and had the pleasure of seeing that arrangement effected.”

There was no room for doubt as to Nova Scotia sentiment when the

Dominion elections in September, 1867, resulted in the return of only

one union candidate in the Province. This was Tupper himself, who

defeated William Annand, Howe’s chief lieutenant. The battle was renewed

at Ottawa early in 1868 when Howe and Tupper presented their case to the

House of Commons. Suddenly Howe joined Annand and other Nova Scotians in

a mission to London to press for the repeal of union. Tupper followed,

resigning the Chairmanship of the Intercolonial Board in order to be

free from obligation to Ottawa, and faced Howe in London. His argument

that the Imperial authorities were for the union, that the agitation

could not succeed, that Nova Scotia could not get along without Federal

assistance, weakened Howe’s resolution. Howe and Tupper returned

together, and played shuffle-board, amiably, with Howe’s associates

looking on anxiously. Once in Canada, Tupper enlisted the hand of Sir

John Macdonald, master diplomat, and in a few weeks Howe was won over by

the promise of better terms, and early in 1869 joined the Dominion

Cabinet. Tupper piloted Howe, broken in health, through the Hants

by-election. Three years later Howe and Tupper, working together at

last, swept Nova Scotia completely, not an opponent of the Ottawa

Government being returned. On the surface the union cause had its

ultimate triumph.

“It is not too much to say,” says Sir Robert L. Borden of Tupper, “that

if he had been a man of less invincible courage and determination, the

project of Confederation might have been postponed for many years.”

Nova Scotia’s “little Napoleon” was not long in Federal politics before

his influence was felt. His natural pugnacity and initiative carried him

along in the House, while Sir John Macdonald soon learned to lean

heavily upon him, though he was not yet in the Cabinet. In 1870 he

launched the idea of the National Policy, which was later adopted by the

Conservative party, and which with variations has remained in effect to

this day. He asked the House if it was advantageous for Canada to long

remain in its present humiliating attitude with regard to trade

relations with the United States.

“Should we allow the best interests of the country to be sacrificed,” he

said, “or uphold a bold national policy which would promote the best

interests of all classes and fill our treasury? . . . Whoever read the

discussions of Congress would see that all we had to do was to assume a

manly attitude on that great question in order to obtain free trade with

the United States. But suppose they resented that retaliatory policy?

The result would be hardly less satisfactory than a reciprocity treaty.

It would increase the trade between the Provinces, stimulate intercourse

between the different sections of our people, and promote the prosperity

of the whole Dominion. Such a question should be fully considered, for

it affected the most important interests of the country, and, properly

dealt with, would diffuse wealth and prosperity throughout the

Dominion.”

So impressed was Sir John Macdonald that he at once took Tupper into the

Cabinet as President of the Council.

But the National Policy was not to be adopted by the country for eight

years. In 1873 the Macdonald Government fell, as a result of the Pacific

Scandal exposure, and were out of office until 1878. Tupper, who was not

compromised in any way by the charges, was a valiant defender of the

Ministry, and when Lord Dufferin, then Governor-General, asked Sir John

Macdonald to resign, Tupper, in a characteristic interview, secured a

reversal of that request. His own version of this meeting is as follows:

“I called upon Lord Dufferin, who said: ‘I suppose, Doctor, Sir John has

told you what I have said to him,’ and was answered in the affirmative.

Lord Dufferin said: ‘Well, what do you think about it?’ I said, ‘I think

your Lordship has made the mistake of your life. To-day you enjoy the

confidence of all parties as the representative of the Queen. To-morrow

you will be denounced as the head of a party by the Conservative press

all over Canada for having intervened during a discussion in Parliament

and thrown your weight against your Government. Nor will you be able to

point to any precedent for such action under British parliamentary

practice.’

“Lord Dufferin said: ‘What would you advise?’ I replied: ‘That you

should at once cable the position to the Colonial Office and ask

advice.’ That was done. Lord Dufferin sent for Sir John Macdonald at two

o’clock that night, and withdrew his demand for the resignation of the

Government.”

The period which followed was one of low fortunes for the Conservative

party. Sir John Macdonald, flung from the heights reached by his success

in the Washington treaty in 1872, was overwhelmed and eager to resign

from the leadership. It was the buoyancy of Tupper that revived him and

induced him to remain head of the party. Both men removed to Toronto,

Macdonald to take up law, living in the “Premier’s house” in St. George

Street,—afterwards successively the home of Oliver Mowat and A. S.

Hardy, Premiers of Ontario— and Tupper to give attention to his

neglected profession of medicine. Between whiles they “mended their

political fences,” and were soon in more cheerful mood.

According to James Young, who was then in the House of Commons, a

remarkable incident occurred in 1876. When the Liberal Budget was

presented, the Conservatives expected a higher tariff, and were prepared

in their criticism to take the opposite policy. Mr. Mackenzie’s version,

as quoted by Mr. Young, that night, after the Premier had been over

chaffing Tupper, was as follows:

“‘I went over to banter him a little on his speech, which I jokingly

alleged was a capital one considering that he had been loaded up on the

other side. He regarded this as a good joke and frankly admitted to me

that he had entered the House under the belief that the Government

intended to raise the tariff, and fully prepared to take up the opposite

line of attack!’”

Tupper was equal to the emergency, and in the remaining years of

Opposition was a merciless critic of Sir Richard Cartwright, then

Finance Minister. The Conservatives gradually gained ground, through the

widespread financial depression, the poor generalship of the Government,

and the hope the high tariff aroused among the people. Sir John

Macdonald was not long in power before the Canadian Pacific Railway

project took a new and definite form. Sir Charles Tupper (who had been

knighted in 1879), as Minister of Railways, recommended a definite plan

in June, 1880, following which Macdonald, J. H. Pope and himself visited

England and arranged with a syndicate for the construction of the

transcontinental line on payment of $25,000,000 and 25,000,000 acres of

land. In presenting the agreement to the House for ratification late

that year, Tupper said:

“We should be traitors to ourselves and to our children if we should

hesitate to secure, on terms such as we have the pleasure of submitting

to Parliament, the construction of this work, which is going to develop

all the enormous resources of the Northwest, and to pour into that

country a tide of population which will be a tower of strength to every

part of Canada, a tide of industrious and intelligent men who will not

only produce national as well as individual wealth in that section of

the Dominion, but will create such a demand for the supplies which must

come from the older Provinces as will give new life and vitality to

every industry in which those Provinces are engaged.”

It fell now to the Liberals to play the role of Faintheart. Edward Blake

said the project was “not only fraught with great danger but certain to

prove disastrous to the future of this country,” while Sir Richard

Cartwright considered the bill “simply as a monument of folly.” Meetings

were held in the country, Tupper following Blake from place to place a

night later, but the bill passed, and the railway was completed by 1885,

but not without mountainous financial difficulties, which at times

threatened disaster.

Sir Charles Tupper’s later public services were as Canadian High

Commissioner in England, where he served almost continuously from 1884

to 1896. His aggressive and energetic temperament found play in

uncounted avenues of usefulness. He returned to Canada in 1891, while

still High Commissioner, to speak against the Liberal policy of

reciprocity with the; United States, and for his partisanship was

severely criticized by his opponents. He was not chosen to succeed Sir

John Macdonald in 1891, and he has declared that he would not take the

position. Writing to his son, C. H. Tupper, from Vienna, on June 4,

1891, on hearing Sir John was dying, he said:

“You know I told you long ago, and repeated to you when last in Ottawa,

that nothing could induce me to accept the position in case the

Premiership became vacant. I told you that Sir John looked up wearily

from his papers, and.said to me: ‘I wish to God you were in my place,’

and that I answered: ‘Thank God I am not.’ He afterwards, well knowing

my determination, said he thought Thompson, as matters now stood, was

the only available man.”

When Tupper responded to the call of the Premiership in 1896, in his

party’s extremity, he was an old but still a courageous man. He placed

his party under one more debt for his unhesitating service. Even in

1900, in his last campaign, at the age of 79, he dashed from meeting to

meeting with the constancy of a beginner. Defeat doubtless came to him

as a relief, for on election night he bade his circle of friends in

Halifax to be of good cheer: “Do not let a trifling matter like this

interfere with the pleasures of a social evening.” The last entry in his

journal for that day said significantly: “I went to bed and slept

soundly.”

Sir Charles lived until October 30, 1915. The sunset of his life in

England was brightened by the tributes and allegiance of friends in both

parties. He had fought valiantly in the days of Canada’s builders. His

loyalty to his country was only equalled by his loyalty to his party.

His last years were varied by occasional visits to Canada. In 1912 he

laid at rest, in Nova Scotia, Lady Tupper, formerly Florence Morse of

Amherst, his, happy helpmeet during sixty-six years of struggle. The

world had entered the crucible of a vast war, and the Dominion saw ahead

a new era for which the Confederation period was but the foundation,

when a battleship bore his remains to his native land. |