|

We began the year 1861

by joining our new ship, and immediately commenced such alterations as

the ‘Hecate’s’ fittings required for the work before her. We had hardly

got on board, however, and had not half “shaken down,” when the

non-appearance of the ‘Forward’ caused so much anxiety that Captain

Richards decided upon going out to look for her. Accordingly on the 4th

we were under weigh in our new ship, and steaming out of the Strait of

Fuca. The ‘Forward’ had at this time been absent quite a fortnight

longer than she ought to have been, and as we knew that heavy gales had

been prevalent outside the Straits, it was natural some anxiety should

be felt for her, although most of us as yet trusted in the general luck

of her commander, Robson (who, poor fellow! has since been killed), for

picking himself up somewhere. Browning, too, who had accompanied the

‘Forward,’ knew the coast thoroughly; and we, therefore, as yet

attributed her absence to some accident in her machinery. Subsequently,

however, we began to feel seriously alarmed for her safety.

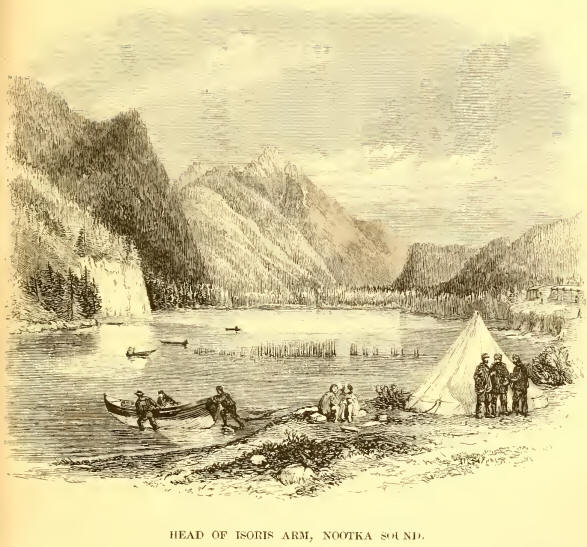

We reached Nootka Sound in the afternoon of the following day, and,

passing Friendly Cove, steamed up to the Boca del Infierno, and anchored

in a small place called Island Harbour. Here we communicated with the

natives, but could only hear that a steamer had been there and left some

time ago. Xext day (6th) we left Island Harbour, and went to the Tasis

village, but without learning anything more. On our way out we

despatched a boat-party to Friendly Cove, and there found a board with a

broad arrow cut upon it, but no notice. This we afterwards learned had

been put up by a Mr. Lennard, who was cruising about the west coast on

the look-out for furs, in his cutter, the 'Templar.’ We remained outside

all night, jogging slowly down the coast towards Barclay Sound, which we

entered next morning, and proceeded to the settlement at the head of the

Alberni Canal. Here we remained all night, but got no further

information, and next morning steamed to Uclulet at the north entrance

of the Sound, where we found five men of the ‘Florentia,’ the vessel

which the ‘Forward’ had been despatched to look for, and which had been

wrecked 12 miles north of this point, together with several of the crew

of the American brig ‘ Consort,’ which had also been lost on the coast

90 miles beyond Nootka. From these, whom we took on board, we learned

that the ‘Forward’ had arrived at Friendly Cove on the 19th of December,

and hearing there of the wreck of the ‘Consort,’ had gone to rescue her

crew; that she returned to Friendly Cove, having-eighteen of the

‘Consort’s ’ crew on board, and, taking the ‘Florentia’ in tow, had

started with her for the Strait of Fuca. Outside Nootka Sound it

appeared that they experienced a considerable swell, and twice parted

the chain by which the ‘Florentia’ was towed, but succeeded each time in

getting it on board again. About 5 in the evening, however, the

‘Forward’ dropped close to the ‘Florentia,’ and Hobson (her commander)

hailed to say he could not tow her any longer, and immediately cast her

off,—or the chain parted again,—they were not sure which. The ‘Forward’

then ran across the ‘Florentia’s’ stem, steering for Nootka, and was

lost sight of in ten minutes, since which they had neither seen nor

heard anything of her. The ‘Florentia’ had afterwards drifted ashore

again, and been totally lost.

Captain Richards, upon a consideration of these facts, came to the

conclusion that if the ‘Forward’ had entered any of the Sounds, the

Indians would have known of it, and that she had probably by this time

got back to Esquimalt. We, therefore, returned thither, reaching it on

the 10th, but to our surprise and alarm, we found nothing had been heard

of her. It was at once determined that the ‘Plumper’ should start in

search of her, this time examining the whole of the west coast, and

communicating with Fort Rupert upon the chance of her having gone round

the island. On the 11th, therefore, the ‘Plumper’ left, and as day after

day passed without our obtaining any news of the missing gunboat from

her or any other source, we, waiting anxiously at Esquimalt, began to

give up all hope.

On the afternoon of the 15th, however, when sitting in my cabin, I was

told that an officer was coming alongside, and on going up the ladder,

great was my surprise to find Browning standing at the top of it! I have

said he had gone as pilot in the ‘Forward,’ and had he delayed making

his appearance for a few days later, it is not unlikely that he would

have found his kit sold as “dead and run men’s effects.” There he was,

however, and he told us he had come in from the ‘Forward,’ which was

outside the harbour, and would arrive in an hour. He explained that they

had parted company with the ‘Florentia,’ on account of the crown of one

of the furnaces coming down, and, returning to Friendly Cove, had

patched this up as M7ell as they could, and started for Esquimalt.

Outside they met strong easterly gales, which blew without intermission,

and so hard that they could make no head against them. After several

days’ struggle, Robson having 20 shipwrecked men on board in addition to

his own crew, began to fear that they might fall short of provisions,

and at last determined to bear up and go round the north end of the

island, knowing that they could get supplies of some sort at Rupert,

which place they reached finally with no worse mishaps on the way than

running short of provisions and coal.

On the 18th the ‘Plumper’ returned from her search, having learned at

Rupert that the gunboat had passed down the Strait, and on the 28th our

old ship sailed for England amid most vociferous cheering from those she

left behind. Our winter work in the office, which I have before made

mention of, went on much as usual; while, on board, the boats were being

fitted up, and other preparations made for the coming summer. The

‘Shark' which had before been only half-decked, was now completely

decked over, and turned into a regular schooner, capable of navigating

the west coast of the island. On the 23rd of February we had official

news of Sir T. Maitland’s assuming command of the station, and changed

our flag for the third admiral since we came out.

By the middle of March everything was ready for a start, the ship

caulked, chart-room fitted, our pinnace converted into a schooner, and

all the boats ready, and on the 22nd we left Esquimalt for the Fraser

River to lay down our second set of buoys at its entrance. The ‘Forward’

went with us to assist in this operation, and we both anchored that

night off Port Roberts. Next day we entered the Fraser and steamed up to

New Westminster, without any let or hindrance. This was subject of great

rejoicing to the people of Westminster, as no steamer of the ‘Hecate’s

size (850 tons) had before ascended the river, and it showed

unmistakeably that it was practicable for large vessels to do so. So

delighted were the people of Westminster, indeed, that they wanted to

entertain Captain Richards at a public banquet, a deputation of citizens

waiting on him with that object. This, however, he steadfastly declined,

representing that all he had done was his duty, and that he had come to

buoy the mouth of their river, not to feast. So they contented

themselves with presenting him with a complimentary address. From the

25th to the 29 th the surveying officers were employed in the ‘Forward’

placing the buoys. The difficulty of keeping these buoys in their

places, which is very great, arises from the number of large trees which

are floated off the banks of the river when the water is high, and come

down the stream carrying everything before them. The buoys now put down

were large spars fitted with a running chain through the heel, and

moored to heavy weights in such a way that anything on a line with them

would only dip them under water and pass over. The bottoms of the

"weights were hollowed out so that they might work themselves down into

the sand, and so keep in their places. Considerable difference of

opinion still exists as to whether these sands drift and change their

position. My opinion is that they do, although not to the extent that

some affirm. In thick weather the leading marks upon them are not of

course visible, and the masters of ships losing their course and

grounding are likely enough to lay their mishap to the shifting of the

sands rather than to the right cause. On the 29tli we crossed to Nanaimo

and filled up with coal, and on the 5th April went to Esquimalt, where

we found that the ‘Bacchante,’ with the new admiral, Sir T. Maitland, on

board, had arrived, together with the ‘Topaze’ and ‘Tartar.’ The spring

weather had now fairly set in, and we felt that working time had

commenced. This winter (1860-1) had been by far the finest and mildest

we had experienced since we came to the island, there being but a few

days’ frost in the month of January, while even then the thermometer

sank only a few degrees below zero. We knew, however, that the season on

the west coast, to which we were going, was later than that inside the

island, and so we waited until the 17th before we started.

We left Esquimalt on the night of the 17th, and anchored in Port San

Juan on the morning of the 18th. I have before mentioned this harbour,

which lies at the entrance of the Strait of Fuca on the north. Some gold

had recently been found in Gordon River which runs into its head, and a

party had started to work it; but although the precious mineral

undoubtedly existed there, it was not found in quantities sufficiently

remunerative to induce them to remain.

On the 19th we reached the head of the Alberni Canal, and anchored about

a mile off the saw-mills. Although we had visited this place before in

the 'Plumper,’ I have as yet given no description of it. As it is

already a considerable settlement, and likely to become of some

importance, it claims, I think, some passing notice.

Barclay Sound, as it is now spelt, at the head of which the Alberni

settlement is placed, should properly, I believe, be “Berkely,” as it

was named by Captain Berkely of the ship ‘Imperial Eagle,’ who in 1787

discovered, or rather rediscovered, the Strait of Fuca. Its eastern

entrance is a little more than 30 miles north-west of Cape Flattery, and

the whole length of the sound is 35 miles. The entrance, which is six or

eight miles across, is filled with small islands and low rocks, many

under water, over which the sea breaks with great violence during the

prevalence of southerly winds, giving to the entrance a greater

appearance of danger than really exists. Into this sound there are

passages from the west and the east, of which the latter, although the

narrower, is to be preferred, from the fact that there are no sunken

rocks in the channel. It is proposed to erect a light on Cape Beale, the

southern cape of Barclay Sound, which will no doubt be of great use to

navigators making the Strait of Fuca. In the winter time, when the

weather is so often thick and foggy, it frequently happens that

observations cannot be obtained for two or three days before making the

land, and the navigator does not like to keep in for Cape Flattery, for

fear of getting under the American coast, where there is a perfect nest

of rocks. A light on Cape Beale would enable him to make the island

shore with considerably less anxiety than at present, and he could find

shelter in Barclay Sound if he preferred waiting for clear weather

before making the Strait, as the winds winch most endanger ships here

blow on to Vancouver shore, and are consequently far into the Sound.

Like all the sounds of the west coast of Vancouver Island, Barclay is

subdivided into several smaller sounds or arms, running five or six, or

sometimes more, miles inland. Of these the Uclulet arm is just within

the west entrance, and inside this, as you coast round the west shore,

is the Toquart, Effingham, Ouchucklesit, and several others, almost all

containing good anchorage. In Ouchucklesit coal has been found, which

will probably be of great value to the settlement. The scarcely less

valuable commodity of limestone of very good quality has been discovered

here. At the mills they used large quantities of it. Previously to its

discovery they were entirely dependant on the clam-shells which the

Indians leave in very large quantities on the beaches where they dig up

the fish. Some of these arms are very curious, running in a straight

line, or very nearly so, 5 or 6 miles between mountains 3000 or 4000

feet high, with a breadth in many places of not more than 50 yards, and

yet 30 or 40 fathoms deep up to the head, which is invariably flat with

a river running through it. Fifteen miles above the entrance, the sound

narrows to half a mile, and the Alberni Canal commences. This continues

at about the same width for 20 miles, where it opens out into a large

harbour, on the east side of which is the Alberni Settlement. Extending

north-west from the settlement is an extensive valley, which terminates

in a large lake 5 or 6 miles from the head of the canal or inlet, and

above this is another large lake, separated from the lower one by a

mountain-ridge. These lakes were each estimated by Captain Stamp, wlio

examined them, to be 30 miles long and 1 to 2 miles broad.

From the southern of these lakes runs the Somass River, which, being

joined-by another river having its rise in the upper lake, flows into

the Alberni Canal. A very great volume of water comes down by this

river, so much indeed that at the end of the ebb-tide the water

alongside the ship was quite fresh, though we lay a mile from its mouth.

On both banks of the Somass, and indeed all over the valley, the soil is

very rich, and the timber magnificent — the Douglas pine (Abies

Douglasii), growing to an enormous size, and the white pine, oak, and

yellow cypress also abounding. Of these, however, more will be said when

I come to speak of the timber of the country generally. This tract of

country has been granted upon lease to the Saw Mill Company, who have a

farm upon it under cultivation, and are commencing a brisk trade in

spars and lumber. It was here that the flagstaff which is erected in Kew

Gardens was cut. As these mills are by far the largest and most

important in the colony, a short description of them may interest the

reader.

They have been erected in a most solid fashion, and at a heavy outlay,

by English labourers, and with English machinery. They contain two gangs

of saws capable of cutting about 18,000 feet of lumber (plank) daily,

and in the best way, as is proved by the high price obtained for it at

Melbourne. Seventy white men are employed at and about the premises, so

that the place has all the appearance of a flourishing little

settlement. Two schooners and two steamers are also employed by the

Company here, the former trading with Victoria and bringing the

necessary supplies to the place. One of the steamers, the ‘Diana,’ a

little tug, also trades to Victoria, and is used besides for towing

vessels up to and away from the mills. The second steamer, the ‘ Thames

’ has not yet reached the colony, but is on her way out from England. In

addition to these, several ships are employed in the spar trade between

the colony and Europe, but the desire of the company is to sell on the

spot.

The Alberni Mills possess several advantages over similar rival

undertakings in Puget Sound, which are now beginning to be appreciated

by merchants, and still more by the masters of ships. One of the chief

of these lies in its accessibility, for Alberni being situated on the

outside coast of the island, the navigator avoids all the journey in and

out of the Straits of Juan de Fuca and Admiralty Inlet, which occupies

ordinarily a week: so that a vessel bound to Alberni, making Gape

Flattery at the same time with one bound for Puget Sound, would be

half-loaded by the time the other reached its destination. Again, when

loaded, the tug takes him to the entrance of Barclay Sound, where he can

wait for a fair wind, while the other, in consequence of the more

prevalent winds blowing into the Strait, has to beat for two or three

days to get outside. In winter this is by no means a desirable spot to

beat about in, for the squalls from the Olympian Mountains are sudden

and heavy, and fogs come on very rapidly. Another consideration, which

carries much weight with the skipper, is that there are no opportunities

for men to desert at Alberni. Of course, when the trade becomes greater

and the country more opened up, this advantage will cease to exist, but

for some time to come men will be very safe there.

There are no port charges whatever at Alberni, and it is a port of

entry, so that vessels can clear from the mills; whereas in Puget Sound

they cannot, and have to call at Port Townshend or some other port to

get their clearance. The scarcity of white pine in the American

territory will probably enable the Alberni mills to compete with their

Puget Sound rivals successfully even in the San Francisco market, and

they are admirably placed for the supply of America, China, and

Australia, with the latter of which countries a remunerative trade has

already been opened. Several foreign Governments have entered into

contracts for these spars, and our own has ordered two cargoes of

topmasts to be supplied. I will now, however, quit this subject, having

to speak more particularly of the qualities of the different woods

growing on this coast, when treating of the resources of the island.

On the 29th I started by land for Nanaimo—a description of which journey

has been already given—returning on the 12th of May. I found that the

‘Hecate’ had gone to Ouchucklesit, and proceeded thither in a canoe the

same afternoon, overtaking the ship at 7 p.m. The boat-surveying parties

were busily engaged by this time at the entrance of the Sound, and the

ship had moved down to Ouchucklesit on the 9th to be nearer them. The

boat parties had returned to the ship once during my absence. Upon their

next visit on the 27th, I joined them for* a week. From this time until

the 9th of June we were all hard at work about the various inlets and

islands of Barclay Sound. On the 3rd the ship moved down to Island

Harbour in the entrance, and on the 9th we went out to sound off the

Straits of Fuca, leaving-two boats behind to finish Uclulet.

We spent a week running lines of soundings backwards and forwards over

an area of 400 square miles, to determine the limits of the bank which

runs off from the island shore for upwards of 20 miles; and a most

unpleasant week it was, and very glad we were when it was over. These

soundings proved, however, of great use, as we found the edge of the

bank to be so steep that a ship may always find her approximate position

by the soundings as she approaches the shore— the depth changing quite

suddenly from 200 fathoms or thereabouts to 40 or 50. Our task being

completed by the 14th, we went right up to the head of the Alberni again

for sights, and commenced painting the ship. On Monday, the 21th, this

necessary although unpleasant job was finished, and wo started for

Esquimalt, having in tow a main topmast for the ‘ Bacchante,’ which Mr.

Stamp sent as a present and specimen to the Admiral. We generally went

about these channels with a good string of things of some kind towing

after us, usually boats which were to be dropped at different places on

our road; and this time was no exception to the rule, for we passed down

the canal towing the topmast, with the 'Shark,’ and one of the

whale-boats, which we cast off at the entrance, they being bound for

Clayoquot to prepare, by sounding the entrance, for our arrival there as

soon as we returned from Esquimalt.

One of the whale-boats, under the charge of Mr. Browning, had been away

since we started on our sounding cruise, and we now went to pick her up

off Port San Juan. We usually took these opportunities for exercising at

gun-drill, as when we were on surveying ground we had other fish to fry;

so that on this occasion the pivot-gun was ready loaded when we opened

San Juan Harbour, and saw Browning’s tent comfortably pitched on the

shore. There is a certain amount of pleasure, I suppose, in disturbing

an unsuspecting fellow-mortal; and although we all knew, from frequent

experience, the annoyance of seeing the ship gliding round some point,

and hearing the boom of a signal-gun when it seemed reasonably certain

that a quiet, undisturbed night might be enjoyed, it was not with much

commiseration for our shipmate that we watched, through our glasses, the

figures rushing out as the boom of the pivot-gun reached them, and the

tent’s sudden disappearance. Browning, who, with the rest of us, was

pretty used by this time to decisive action in packing and shifting his

quarters, lost no time; and in 20 minutes after our signal, his boat was

cleared and hoisted up, and we were flying down the Strait with all sail

set to a fair wind.

On the 26th the mail steamer arrived, but with no mail.

Mr. Booker, our consul at San Francisco, sending instead the pleasant

news that the Americans had refused to carry the colonial mails without

payment any longer. We did not think that the Company were in the least

to blame, hut it was hard upon us, who had had nothing to do one way or

the other with the postal arrangements. The American Company had been

allowed to bring and take our mails for years without any offer of

remuneration being made, and had the colonists alone suffered, none of

us would have felt disposed to pity them. Without any reference to

politics, we could not help wishing sincerely at the time that the Derby

ministry had remained in office, as it was understood that it was their

intention to grant a mail subsidy for the colony. The Company that owns

the saw-mills at Alberni had made proposals for carrying the mails, and

their agent told me that a subsidy of 20,000?. for conveying them

between San Francisco and the colony had been promised them, and that

nothing but the formal confirmation of the contract was wanting when the

Government went out.

The agent also represented to me that the refusal of the incoming

authorities to ratify the contract arose from the fact that so few

letters left England addressed to British Columbia. The reason of this

wag, he said, that all men of business at home gave instructions that

their letters should be directed under cover to their agents at San

Francisco, on account of the uncertainty of the conveyance of the

ordinary mails beyond that place. Correspondence, indeed, with the

colony was at this time most uncertain— the majority of letters intended

for settlers there being directed, “Post Office, Steilacoom, Washington

territory.” This mode of direction used often to puzzle the post

officials and amuse us. It was printed upon all the official envelopes,

but the cause of its origin and continuance was a mystery which no one

could explain.

Steilacoom never was the post-office of Washington territory while we

were there; and even if it had been, why letters should he directed to

that place, which is 60 miles up Admiralty Inlet, when there was a

post-office at Port Towns-hend, in its entrance, was most unaccountable.

To make the matter still worse, some people took to having “Oregon”

printed or written also in a conspicuous place on the envelope —no doubt

wholly unaware of the fact that Oregon and Washington are two distinct

territories, each somewhat larger than France.

On the 2nd of July, at 9 p.m., we again left Esquimalt, having on board

five-and-twenty of the pillars which had been sent out from England to

mark the 49th parallel boundary-line. We took them to Semiahmoo Bay, and

landed them on the parallel; and, it being low-water when we arrived,

they had to be carried about a mile across the sand. Twenty-two only

wore landed at the boundary, and the other three taken to Port Roberts,

where we left them the same afternoon, and proceeded to Nanaimo. These

periodical visits to the boundary-line gave us some idea of the rapid

growth of the bush in this country, and showed us how completely futile

the mere cutting down of trees to mark a boundary in such a country is.

We knew the position of the boundary-line, but could not find the stump

which had been driven in to mark the spot; and when I tried to penetrate

along the line which could be distinguished from above easily enough by

the gap in the larger trees which, of course, had not yet grown again, I

found the undergrowth so thick as to be what people unused to that

country would consider quite impenetrable. Upon another occasion we

witnessed a still more speedy obliteration of such a trail by the

undergrowth of timber. When we were at Port Roberts about a year after

the trail had been cut, it was necessary for some purpose to pass

through it. But, although we hunted for an hour or more among the bush,

no entrance to the trail could he found.

We remained at Nanaimo coasting until the 12th; the ‘Grappler’ taking

the rest of the beacons to Smess River, and there depositing them. I

should have said that these beacons or pillars were constructed of

cast-iron, pyramidshaped, and having the words “American Boundary” on

one side, and “Treaty, 1844,” on the other. They were hollow, and fitted

to screw or bolt on to a stone or block of wood, the weight of each

being about 100 lbs.

On the 13th we left Nanaimo, reaching Cormorant Bay at nine that night;

and next day we went on to Fort Rupert (Beaver Harbour).

We occupied our time at Rupert till the 17th, getting sights, &c., and

cutting and dragging out of the bush five trees of the yellow cypress

for repairing our boats, &c., for which and similar purposes, as I have

before said, this wood is the best I have ever seen. On the 17th we went

on to Shucartie Bay, and spent the 18th there, while the cutter and one

whaler sounded on theNewittee Bar. We tried the seine (net) in Shucartie

Bay, but only caught about thirty salmon.

On the 19th we steamed through the Goletas Channel towards the north end

of the island, but the fog came on so thick that we anchored on the edge

of the Newittee Bar. We must have been nearer the edge indeed than we

thought, for we soon found ourselves drifting off it, and the ship

cruising about with 50 fathoms of chain hanging from her bows.

Fortunately, it cleared about this time, so we hove the anchor up and

proceeded out. At noon we reached Cape Scott, and then went out to look

at the Triangle Islands, which lie off it, and at dark shaped our course

for Woody Point, or Cape Cook, halfway between the north end of the

island and Nootka Sound. We passed this spot next morning at daybreak,

and by three in the afternoon were off Nootka.

We were bound, however,

for Clayoquot Sound, which lies between Nootka and Barclay Sounds; so on

we went, and reached the entrance at 8 p.m. It being then too dark to

enter, we had to do what seamen are proverbially fond of— “ stand off

and on ” for the night. At daybreak we found ourselves off Port Cos—so

named by Meares, and described by him in terms which were calculated to

lead us to suppose that, had we wanted it, safe anchorage might be found

there. When, however, the spot he had thus described was surveyed, it

was found that a sand-bar completely blocked up its entrance. The

whale-boat we had to take up was inside, and at six she came on board;

and we went back again to the northern entrance of Clayoquot Sound, and

in to an anchorage which she had found for us, where we moored,

intending to remain till we had surveyed all the Sound— little thinking

what was in store for us, and what mishap would befal us before we

should again reach Esquimalt.

We all set to work surveying the various arms of the Sound, and the

weather continuing fine our task progressed satisfactorily. We found

sundry arms and passages hitherto unknown, and discovered that one

previously marked upon the charts as Brazo de Topino was inaccurately

described— its extent proving to be not more than half that laid down by

former explorers.

On the 7th of August I returned to the ship, after a ten-days’ surveying

cruise, and walking as usual into the chart-room, was told that the

Indians had brought a mail across from Alberni, and that my letters were

in my cabin. I was going down for them, when the Captain came on deck

with a service-letter in his hand, and said, “Here is something that

concerns you as First Lieutenant of the ship.” I instantly apprehended

some question of minor punishments, and was preparing to defend my

conduct, when he read out: “I have to inform you that Lieutenant B. C.

Mayne has been promoted to the rank of Commander,” &c. This intelligence

was so sudden and wholly unexpected, that it was not until I had read

the document that I fully realised it. Only the night before my return

to the ship, as I lay by my watch-fire smoking and thinking of the

future, I had come to the conclusion that I should remain with the

‘Hecate’ until she was paid off; and now I knew that this sudden change

in my prospects would lead, upon our reaching Esquimalt, to my being

ordered to return to England. As it happened, however, my connection

with the ‘Hecate’ did not terminate so abruptly as I then expected, and

I remained with her for three months from this date.

On the 15th August we started for Alberni, to get sights again, reaching

it the same night. On the 17th we again left, intending to pick up

Gowland, who was away on surveying service off Nootka Sound, and then

going round the north end of the island, to finish some work at Cape

Scott, and return inside the island to Nanaimo and Esquimalt. The next

morning at 10 we were off Point Estevan (Nootka Sound), and Gowland

joined us. A fresh north-wester was then blowing, and during the

afternoon it increased into a gale. This put a stop, of course, to

sounding, and as the Captain knew that he would not be able to land on

the north end of the island for some days after a gale, he determined on

giving Tip work for the present, and going in by the Strait of Fuca. At

8 p.m. we were “ fixed ” and steering for the Strait, and at 10 we ran

into a thick fog. This was nothing at all unusual, and as we knew our

ground, or water—indeed I may say both—by heart, we jogged along about

seven knots, sounding every half-hour.

About 3 o’clock, as we approached the Strait, the speed was eased to

five knots, and the course altered a little; and at 4 o’clock we got a

cast of 19 fathoms. This puzzled every one. We knew the water was much

deeper than this on the south side of the Strait, and it was agreed by

all that we must have got rather far on to the north shore. The ship was

accordingly kept south a mile and a half, and then up the Strait again,

going four knots an hour, the fog continuing as thick as “pea-soup,” to

use a nautical simile. At 8.30, when I relieved the captain who had been

all night on deck, he said “Three or four hours more and you will be

packing up your traps,” and went down to his breakfast. He had hardly

reached his cabin, when he heard the orders, “Hard a port!”—“Stop her!”

—“Reverse the engines!”—shouted from the bridge, and rushed on deck just

in time to find the ship landed on a nest of rocks, over which the surf

was sullenly breaking in that heavy, dead way which it does when it has

a long drift of ocean open to it but no wind to lash it into foam. I had

jumped on to the bridge, and seeing her head fly round in answer to the

helm, thought we were going clear, but no such luck was in store for us,

and up she went. Nothing but rocks were to be seen all around us, and we

were all equally puzzled to know where we were, how we got there, and

how we should get the ship off. That we were close to the shore we soon

found, for high up over our foretopmast-head, as it appeared from aft,

the summit of a cliff, with a few pine-trees upon it, showed itself.

Fortunately for us, the noise of the steam escaping was heard by the

master of a small schooner, which we afterwards found was lying close to

us, and we soon saw two white men, in their usual costume of red flannel

and long boots, paddling to us in a small canoe. Getting them on board

we discovered that we were two miles inside Cape Flattery, that the

cliff we saw was a small island close to the main, and that about 50

yards from us lay two small schooners in a little basin formed by the

rocks. While this information was being gathered, both paddlebox boats

had been got out, the small boats lowered, and the waist anchor placed

in the paddler and laid out astern. During the time that this was being

done, the ship swung broadside to the rocks and began to bump

fearfully,—the masts springing like whips,—and we began to think it was

all up with the poor ‘Hecate.’ Presently as tlie tide, which was rising,

came in and then receded, she gave two tremendous crashes, sending us

all flying about in different directions. At the second crash the chief

engineer ran up from below with the report that the cross-sleepers had

started and the bottom of the bunker fallen in, and that another such

bump would send the engines through her bottom. This was cheerful

intelligence, and everything was got ready for a sudden departure in the

boats. Our friends in the schooner had previously informed us that if

she held together till the tide rose a few inches, she could get in

between the rocks to where his vessel lay. The stern cable had been

hauled on for this purpose, but with no effect, when suddenly she

slipped a little off the rock and then forged ahead. Instantly the stern

cable was let go, and she glided quietly in between the rocks and

alongside the schooner. Ko mortal could have put her there on the

calmest, smoothest day, but there she was, and right thankful for our

most merciful escape were wre, who a few minutes before, could see no

possible chance of saving her. We let go an anchor to hold her until the

sleepers of the engines could be cut away to enable them to move, and,

sounding the well, found she was making water at the rate of six inches

an hour. This was quite an agreeable surprise, for, from the hammering

she had received, we thought the bottom must have been half-knocked out.

Finding the engines would soon be in working condition, it was

determined to push on for Esquimalt. It was quite necessary that we

should go somewhere without delay, for had a breeze sprung up we should

have been as badly off’ where we now were as on the rocks. Here again

the master of the Yankee schooner, was of service. The passage by which

we must pass out was very little more than the ship’s breadth across,

and lay between two sunken rocks. He took two of our whale-boats,

anchoring them over the rocks between which our channel lay, and then,

assisted by an Indian, whom he brought with him, took ns out. All this

time the fog was as thick as ever, but when we got two or three miles up

the Strait we passed out of the fog-bank as suddenly as we had entered

it; all ahead being perfectly clear. This fog had, the master of the

schooner told us, hung at the entrance of the Strait for five days; and

he said it frequently occurred that a local fog of the sort kept about

there for weeks. This man showed all the readiness and nerve of his

countrymen, and was certainly of great service to us. When we were

fairly outside, he said, “Now, there is plenty of water round the ship,

and I’m almighty dry! if you’ll give me a chart, Captin, and a bottle of

rum, I’ll think of you often.” I need hardly say he was abundantly

supplied, and expressed himself very thankful. The Admiralty afterwards

sent him a spy-glass for his services, but he, falling, I fancy, into

some lawyer’s hands, sent in an exorbitant claim for salvage which has

not yet, I believe, been settled. We reached Esquimalt that evening

without further damage or accident, the leakage continuing at the same

rate,— and anchored the ship in Constance Cove, after as narrow an

escape from total loss as any ship ever had. We were altogether 35

minutes beating on the rocks, and nearly an hour from the time of

striking till we were quite clear again; our fate depending upon whether

the tide would rise, as it did, sufficiently to float her before she

gave another bump, which "would in all probability have finished her. I

should perhaps have said, the ship’s fate,—for calm as it was, and close

to shore, we should probably have got all the men to land; although an

operation of this sort, which appears quite easy as long as you have a

few planks to stand on, becomes rather difficult with a ship breaking up

under you.

Next morning, Tuesday, 21st August, an examination was commenced by the

diver and flag-ship’s carpenter. The former after two days’ examination

reported about 25 sheets of copper off under the starboard wheel, and

three heavy crushes in the ship’s side; several sheets of copper off

under the port quarter, 16 under the port wheel, and another heavy crush

there; part of the fore-foot and false keel forward gone, with several

other sheets of copper off in various places. Inside the carpenter

reported 14 floors damaged more or less, four binding-streaks requiring

shifting, one butt of binding-streak on port side leaking badly, with

the first futtocks probably started. Upon this state of affairs being

made known, it was decided by the Admiral that we must go to San

Francisco to be docked, and that before we started the diver should

patch up as well as he could, by stuffing tarred and greased oakum into

the holes, nailing over that the tarred blanket or felt supplied for

that purpose, and sheet lead above it. This took him six days, and most

capitally he did his work: I never saw a man work so long at a time as

he did, sometimes remaining down more than an hour without resting. I

may here mention, for the information of nautical readers, that we found

tarred blanket answer much better than the felt supplied by the service

for such a purpose. The felt was too thick to suck into the cracks; and

when it became saturated it swelled so much the diver could not work it,

and being pressed together, and having no weft or thread through it, the

action of the water separated it and wore it away while he was preparing

the lead to cover it. Having a great deal of lead to put on, we found it

much more convenient also to make nails for the purpose, longer than

copper (2J inch) and with flat heads, one inch in diameter. Where the

wood was much bruised the service nails proved too short, and the heads

so small that the diver could not see to hit them, and was constantly

dropping them and hitting his fingers.

On Thursday (29th) the damages were so well stopped that we were only

leaking one inch an hour; and we took in our coal and got ready for sea.

A survey was then ordered to be held, to report whether or not it was

safe for us to go to

San Francisco alone. It was decided that we ought to be attended by

another ship; for although while in harbour we appeared right enough, no

one could say what the ‘Hecate’ could or could not bear if she got into

a gale of wind. Accordingly the Admiral ordered the ‘Mutine’ to

accompany us as far as Captain Richards thought necessary.

Upon our arrival at Esquimalt, I went on board the flagship for my

commission, expecting at the same time to be told to return home. To my

surprise, however, I was informed that no orders to supersede me had

been received; and that I must remain till my relief came. This did not

disappoint me so much as it would have done had nothing happened to the

ships, for I did not like to leave her in her present dilapidated

condition, and I had determined to go to San Francisco in her even if I

were ordered home.

I will pause ere I take the reader with me on this cruise, which for me,

terminated in Southampton Docks, to give a slight summary of the

resources and capabilities of the country, and of the habits and customs

of the natives. |