|

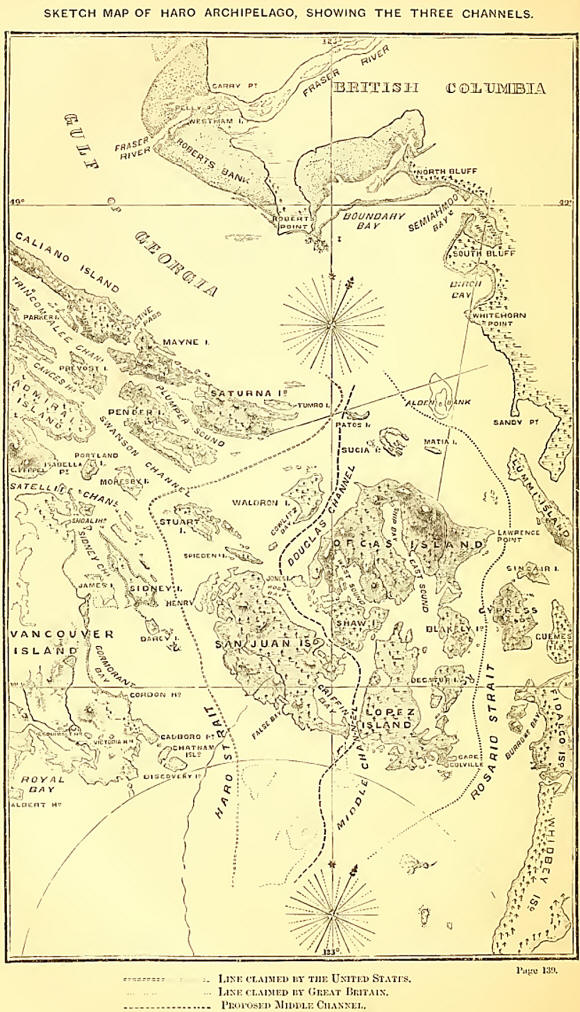

July, 1859. — The

Boundary Commissioners had been all this while working to little effect.

The treaty concluded in 1844 between the English and American

Governments was, as I have before said, somewhat vague. It set forth

clearly enough that the boundary-line should follow the parallel of 49°

north latitude, to the centre of the Gulf of Georgia; but it was at this

point, as the reader may remember, that the difficulties attending its

interpretation began. Thence the treaty stipulated that the line should

pass southward through the channel which separates the continent from

Vancouver Island to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The channel. But there

were three. Were the most eastward of these meant, such a construction

would give possession of all the islands of the Gulf to Great Britain.

On the other hand, should the line, as the American Commissioners

contended, be taken to pass down the Haro Strait, these islands would

pertain to them. Reasons, which I have previously given, exist which

prevent my making any remarks upon the merits of the matters in dispute

between the Commissioners of Great Britain and the United States, or the

results which followed them. I may only say, that it was at this time,

while the question had been referred by the Commissioners to their

respective Governments, that General Harney, who had lately been

appointed to the command of the United States troops in the territories

of Oregon and Washington, without any notice, landed soldiers upon the

island of San Juna, who still remain there.

The same reasons which keep me silent upon this proceeding of the

American General prevent my doing more than allude to the angry

excitement which it caused in the colonies and at home. The events of

that period will still he fresh in their memory of my readers. It will,

therefore, be remembered how nearly war between the two countries was

approached, and by what judicious and timely arrangements it

was-averted. I will merely remark, in conclusion, that, during the

present domestic troubles of the American people, this dispute is

temporarily shelved. San Juan is at present held by equal bodies of

troops of Great Britain and America, and the question remains open for

settlement at some future period.

August 5th.—The flagship arrived, with divers on board, who, upon

examining the ‘Plumper,’ found that she had received so much damage that

it was determined, so soon as the coming winter-work was finished, to

proceed to San Francisco, where the necessary repairs could be made.

August 19th.—A report reaching the Governor of some settlers in Burrard

Inlet having been seized and detained by the Indians, wo were despatched

thither to investigate this matter, but, upon our arrival, we found the

report untrue.

I will take the present opportunity of giving a short and general

description of the more important of those long arms of the sea, or

inlets, which, as a glance at the map will show the reader, stretch at

comparatively small intervals inland along the coast of British

Columbia. Some of these were not surveyed until a period considerably

later than the time of which I am now writing, while others are still

unexplored. It must be many years before these shores can be of any

value to the new colony; and it is mainly with the hope of discovering,

from the head of one of them, a more direct route or routes to the

gold-fields on the Upper Fraser than that afforded by the river, that

exploring parties have been, and still are, busy examining them.

All these inlets possess certain general characteristics. They run up

between steep mountains three or four thousand feet in height; the water

is deep, and anchorages far from plentiful; while they terminate, almost

without exception, in valleys,—occasionally large and wide, at other

times mere gorges,—through which one or more rivers struggle into the

sea. They may be said, indeed, to resemble large fissures in the coast

more than anything else. In the days of Vancouver these arms of the sea

were diligently searched in the hope of discovering through one of them

the long looked-for passage that should connect the Pacific and Atlantic

Oceans. It was not indeed until after many successive disappointments

that Vancouver seems to have relinquished this hope; and although of

course some inaccuracies have been found in his charts of these parts,

their general correctness, together with the amount of labour they must

have cost him, and the patience and perseverance with which he forced

his vessels through intricate passages difficult and dangerous even to

steamers, deserve more credit than he ever obtained.

The southernmost, and as yet the most important, of the inlets of

British Columbia was named, by Vancouver, “Burrard,” after a friend of

that name in the Royal Navy. This inlet differs from most of the others

in possessing several good anchorages. It is divided into three distinct

harbours, which are separated from each other by narrows, through which

the tide rushes, with such velocity as to render them impassable by any

but powerful steamers except, at slack-water or with the tide.

The entrance of Burrard Inlet lies 14 miles from the sand-heads of the

Fraser River. English Bay is the anchorage immediately inside the

entrance on the south side and is of considerable importance to vessels

entering at night, or when the tide is running out through the narrows,

affording them an anchorage where they can wait comfortably until

morning or turn of tide, instead of drifting about the place. Two miles

inside the first narrows is Coal Harbour, where coal has been found in

considerable quantities and of good quality, although the demand is not

yet sufficient to induce speculators to work it in opposition to the

already established mines at Nanaimo. Six miles above Coal Harbour, the

inlet divides again into two arms; one of which runs inland about ten

miles, the other opening into Port Moody, which forms the head of the

southern arm. Port Moody is a very snug harbour, three miles long, and

averaging half-a-mile wide, though only 400 yards across at the

entrance. It is the possession of this port, with its proximity by land

to New Westminster upon the Fraser River, from which place it is distant

but five miles, which gives to Burrard Inlet its present importance.

During the winter the Lower Fraser is sometimes frozen up, and the only

access to British Columbia then open is by the way of Burrard Inlet and

Port Moody. Hither the steamers have to take their passengers, mails,

and cargo; whence, by a short, good road, they are conveyed to New

Westminster. During last winter (1861-62), winch was unusually severe,

the Fraser was entirely blocked up; and this way, and an out-of-the-way,

inconvenient trail of seven miles from Mud Bay, inside Point Roberts,

were the only routes by which the interior of British Columbia could for

some considerable time be reached.

Immediately north of Burrard Inlet is Howe Sound, the north point of the

former forming the south shore of the latter. This sound runs inland for

about 20 miles, and is wider than the other inlets, having a breadth at

its entrance of six miles. At its head is a wide, extensive valley, the

soil of which is very good, and through which several rivers run into

the inlet: the largest of these, the Squawmisht, is navigable for 20

miles for canoes. From this point, which, however— so tortuous is the

river — is only distant ten miles from the head of the sound, a road

might, with no great difficulty, be cut to Port Pemberton, on the north

end of the Lilloett Lake, the distance being only 40 or 50 miles. I

examined this route in 1860, and found it perfectly practicable; but as

a road between Port Douglas, at the head of Harrison Lake, and the south

end of the Lilloett Lake had already been constructed, it was not

thought advisable to make another so near it. Had this route met the

Fraser above instead of below Cayoosh, it would have been worth cutting

at any expense; but coming out where it does, its construction would not

have been of sufficient benefit to the colony to have justified the

great outlay which must have been incurred in making it.

Next to Howe Sound is Jervis Inlet, a narrow arm running inland 45

miles. Vancouver appears to have thought this the most promising of all

the inlets he had explored for the great object of his search ; and

experienced great disappointment when, after sailing up it for several

days, he reached its head. It seems strange that such an experienced

explorer should have expected that so narrow a passage—its greatest

breadth after the first ten miles being but two— would be found to

divide the American continent from shore to shore.

It was for some time thought that a highway to British Columbia would be

found to exist up this inlet; and, with the view of ascertaining its

practicability, I was instructed to start from the head of Jervis Inlet,

and make my way to the Fraser Kiver. An account of this journey and its

unsuccessful issue will follow in its place. Whilst making it, I

constantly interrogated the Indians who accompanied me as to the

probability of a way existing from the head of Toba or Bute Inlets,

which run up from Desolation Sound, and arc the two next inlets

northward of Jervis. From their answers,

I was for some time under the impression that Bute Inlet was the place

whence a start might be made for the Fraser with every prospect of

success. But upon returning to Victoria, and submitting the accounts of

my informants to the scrutiny of an interpreter, and making them map out

in their own way the route that they suggested, I came to the conclusion

that the route they spoke of led, not to the Fraser Fiver, but to Lake

Anderson.

It may seem strange that Indians living at Jervis Inlet should know the

country about Desolation Sound so well, seeing that the two arms of the

sea are distant from each other 60 miles, and that the inhabitants of

each inlet are constantly at war. The tribe, however, to which my guides

belonged, although in the summer dwelling by the coast, were settled

really at Lake Anderson, from which neighbourhood they migrated to Howe

Sound, Jervis, Bute, and Toba Inlets, to fish, and were, therefore,

likely to be well acquainted with the country through which at such

times they must pass on their way to the coast. They were called

Loquilts, the proper Indians of Jervis Inlet being named Sechelts.

From these Indians I ascertained that the Bridge River, one—the

north—branch of the Lilloett, together with the Sqiiawmisht and the

Clahoose Kivers, which empty into Desolation Sound, all take their rise

in three or four small lakes lying in a mountain basin some 50 or 60

miles from the coast due north of Jervis Inlet. Mr. Downie, when

exploring Bute Inlet with a view to a way from the coast inland, went

four or five miles up the Clahoose River, which he described as large

and broad, running in a north-east direction. “The Indians,” he wrote,

“told me it would take five days to get to the head of it. Judging from

the way a canoe goes up such rivers, the distance would be about sixty

miles, and it must be a long way above the Quamish (Squawmisht), and not

far from the Lilloett. The Indians have gone this route to the head of

Bridge River, and it may prove to be the best route to try. It is very

evident there is a pass in the coast-range here that will make it

preferable to Jarvis Inlet or Howe Sound. If a route can be got through,

it will lead direct to Bridge River.”

It is now three years since Mr. Downie made the above statement; and I

think it is probable that he has long since changed the opinion he then

expressed as to the route to the Bridge River being the most practicable

and best of those proposed to the Upper Fraser. So little, however, is

known of this valley—and that little comes from Indian information —that

the route advocated by Mr. Downie may yet be found to equal his

expectations of it. Since my return from the colony it has been again

examined and adopted by a company, who propose at once to open it up. It

is asserted by them that this way is nearly twenty miles shorter than

the Bentinck Arm route to Alexandria, and that no serious obstacles

intervene to prevent striking the Fraser at a point where steamers can

be put on to ply on the Upper River. The right to construct this route,

and to collect tolls on the pack-trail for five years, at 1J cents per

lb., and 50 cents for animals—with, should a waggon-road be constructed,

5 cents per lb. toll—has been conceded to them. In their prospectus the

distance of the route proposed is set down as 241 miles, of which 83

miles are river and lake navigation, and 158 land-carriage, offering an

advantage over the rival route by Bentinck Arm, which has a longer

land-carriage. Before this summer is out, the question of superiority

will in all probability be settled. '

The next inlet, north of Bute, is Loughborough. Beyond are Knight Inlet

and Fife Sound, of which comparatively little is known. In 1861 Mr.

Downie went up Knight Inlet and discovered plumbago, which, when tested,

did not prove to be so rich as he at first sight thought it.

The entrance to Fife Sound is marked by a magnificent mountain on its

north side, which Vancouver named “Stephens,” after the then First Lord

of the Admiralty.

Above this point up to our coast boundary, in 54° 40' north latitude, is

a succession of inlets known only to the Indians who inhabit them, and

some of the Hudson Bay Company’s employes. One of these, through which

it is thought by many that the much-desired road to the interior of the

country will be found to lie, “ Deans Canal,” has recently attracted

considerable notice. The entrance to this inlet is about 80 miles from

the north end of Vancouver Island; it runs inland some 50 miles, under

the name of Burke Channel, and then divides into three arms: one, Deans

Canal, running nearly north for 25 miles; the others, called the North

and South Bentinck Arms, pursuing north-easterly and southeasterly

directions. By one or other of these channels it is pretty confidently

expected that a good available route to the interior will be found to

exist. No doubt attention was drawn to this spot not a little from the

fact, that years ago Sir Alexander McKenzie did actually penetrate from

the interior to the sea here. Subsequently it was known that a Mr.

McDonald had found his way from Fort Fraser to the coast, coming out at

Deans Canal, and, it was said, making the journey with ease and

expedition; while later, letters were conveyed more than once by some

such route, by Indian messengers, from the Hudson Bay Company’s steamer

'Beaver,’ lying in the Bentinck Arm, to the officer in charge of Fort

Alexandria, high up the Fraser River.

When Sir Alexander McKenzie explored this part of the country, he

appears to have ascended the West-road River from the Fraser, and then,

crossing the ridge forming the watershed, to have descended to the sea.

His route has never been exactly followed; but in 1860 Mr. Colin

McKenzie crossed from Alexandria to the same place on the coast, viz.,

Baseals’ Village, or Bell-houla Bay, in thirteen days by way of

Chilcotin Lake. His party travelled the greater portion of the way on

horseback: Mr. McKenzie told me that they might have taken their animals

all the way by changing the route a little. On their way back, indeed,

they did so. The ascent to the watershed was, he said, so gradual, that

they only knew they had passed the summit by finding that the streams

ran west, instead of east. Since that time another gentleman, Mr.

Barnston, has travelled by much the same route. His journey is described

in a letter which he wrote to Mr. P. Nind, Gold Commissioner at Cariboo,

in July, 1861, and which, as illustrating the character of the country

and the obstacles met with in the construction of trails, I am enabled,

by the kind permission of that gentleman, to give to the reader:—

“We left Alexandria on the 24th May last, and after the loss of several

days from accidental causes, such as missing trail, &c., arrived at Lake

Anawhim on the 8th June. We left this place on the 10th. On the 12th we

camped in the Coast Range. On the 13th we descended into the valley of

Atanaioh, or Bell-houla River, and camped a few miles down. Here we left

our horses with Pearson and Ritchie. On the evening of the 17th McDonald

and I, accompanied by Tomkins, started on foot for the coast. We arrived

at the Bell-houla village, Nout-chaoff, early on the morning of the

19th. Here we obtained a canoe and descended to Kougotis, the head of

the Bell-houla (North Bentinck Arm), in six hours. The cause of our

horses being left behind was the swollen state of the mountain-torrents

running into the Bell-houla River. These streams are, however, quite

small and narrow, and could be bridged at little expense. On the 24th we

left Kous-otis to return in the same canoe, and arrived at Nout-chaoff

on the 25th. The trail between the two villages is good. From

Nout-chaoff to camp it took us two days, a distance usually travelled by

Indians with packs in one. On the 30th we broke up camp on Bell-houla

River, and arrived in Alexandria on the 10th, travelling moderately with

packed animals. The Bell-houla River could be made navigable for

light-draught steamers as far up as Nout-chaoff, and perhaps above. From

thence pack-trains could make Alexandria, or the mouth of Canal River,

if a trail were made there, easily in 14 or 15 days. The trail to Canal

River would probably have to diverge from the Alexandria trail at

Chisikut Lake about 75 miles from Alexandria. The trail runs the whole

distance from Alexandria to Coast Range on a kind of table-land, which

is studded in every direction with lakes and meadows: feed is plentiful.

The streams are numerous, but small and shallow; in fact, mere creeks.

There are some swamps, which require corduroying. There is plenty of

fallen timber; but it is light and could easily be cleared. There is

also a kind of red earth, which is in places very miry; the cause of

this is I think, want of drainage. This miry ground and the swamps are

the greatest objections that can be urged against the road. The swamps,

however, have one advantage over such places generally,—that is, in

their foundation, which is rocky and strong. The trail might be

shortened in some places, but not a great deal. We made the distance

from our camp on Bell-houla River to Alexandria easily enough in 11 days

with packed horses. The trail is, with the exception of the descent of

the Coast Range, comparatively level, and could easily be made a good

practicable road. The descent on to the Bell-houla River is not by any

means steep, with the exception of a slide, down which we, however, took

our horses. This slide might be avoided, or could be easily overcome by

a zigzag trail. The trail would have to be considerably improved before

pack-trains could pass over it. When the Coast Range is passed there is

no perceptible ascent.

“From the place where you first strike the Bell-houla River in the Coast

Range, the trail runs along its bank through a deep gorge or pass in the

mountains the whole way to the coast. There is, however, another road

from Lake Anawhim, which strikes the river at Nout-chaoff, which the

Indians informed Us was the better road. They also told us that if we

had taken this road we could have reached Nout-chaoff with our horses,

as we should have thereby avoided the worst part of the other road and

the torrents. Kougotis, the head of the inlet, would be the head of

navigation for sea-going vessels.

“We think that if a road were made from the Bell-houla Inlet, to strike

the Fraser somewhere about the mouth of the Quesnelle River, and from

thence into the Cariboo, &c., a considerable saving in the cost of

transportation would be effected. We can hardly make an approximate

estimate even of what it would cost to make the trail passable; but it

would not cost much considering the distance and style of country, and

could easily be made available for next summer’s operations.”

If The reader will follow on the map the line between the Bentinck Arm

(Bell-houla) and Alexandria, he will see that it runs straight east and

west between the two places for 160 miles. This is the route to the

gold-fields, south of that taken by Sir A. McKenzie, which is proposed

to be adopted, and to open up which another company, in opposition to

the Bute Inlet scheme, has been organised. It is affirmed that the road

becomes open and practicable for animals in the beginning of April, and

that the snow at Bell-houla and the main plateau above it disappears

early in the year. At present and for some time to come no accommodation

for travellers can be expected along this route; but in reply to this

objection it is urged that the journey is comparatively short, and may

be walked without a pack in seven days; and that the Indians of the

various tribes through which it will be necessary to pass are not only

friendly but seem anxious for white settlers to come, inquiring

constantly when the Boston and King George men may be expected, and

looking forward to remunerative employment in packing to the mines.

The following account of this route has also been given by one of its

projectors, who assumes to speak from personal experience:—“My

suggestion would be, let a man take up sufficient provisions for the

road; or if he wishes to avoid the heavy outlay which a poor miner must

experience before he has struck a claim, let him take sufficient to last

him three or four weeks, and pack one, two, or three Indians, as the

case may be. I assure him he will find no difficulty in procuring

Indians. Nootlioch (an Indian lodge) is 30 miles up the river; for 15

miles above this goods can be taken in small canoes. Narcoontloon is 30

miles; a good road with the exception of one bad hill. Here there is

another Indian lodge, from which it is 50 miles to Chilcotin; good

trail, perfectly level. From there it is 60 miles to Alexandria, or

about 70 to the mouth of Quesnelle River. The trail from the top of the

Nootlioch hill is for foot-passengers as good the whole way as any part

of the Brigade Trail, with the exception of one or two places, where

there is a little fallen timber. The trail follows a chain of lakes, and

could consequently, if taken straight, be made much shorter, and also

avoid much soft ground. Game and fish are abundant on the road: I caught

several trout with a string and a small hook and a grasshopper on my way

down. The Aunghim and Chilcotin Indians have a good many horses, which

might be turned to use for packing.”

Alexandria, however, which is the proposed terminus in this route from

Bell-houla, is some 50 or 60 miles south of those diggings, which are

now the most profitable in the country, and which, under the general

name of the Cariboo gold-fields, extend from the lake of that name to

Bear River, and are likely to extend still farther north, should the

opinion of many of the miners that the richest diggings still remain to

be found on the Peace River, northward of that spur of the Rocky

Mountains, which turns the course of the Fraser southward, prove

correct. It seems, therefore, likely that the line of route proposed by

other adventurers, running from Dean’s Canal, in a north-easterly

direction, to the Nachuten Lakes, and along the river of the same name

to Fort Fraser, may bear off the palm, particularly if, as is very

probable, Stuart River be found navigable for steamers from that place

to Fort George, where it meets the Fraser.

In the summer of 1859 Mr. Downie explored a still more northward route

from Fort Essington, by a river called by him the Skena, but which must

be the same as that known inland as the Simpson or Babine, and which

flows from Lake Babine. This route is less direct than any of the

others, and is so far north as to be unavailable for the greater part of

the year. Mr. Downie’s interesting account of this journey will be found

in the Appendix. It will be seen that he reports the country through

which he travelled to be auriferous, that ho found evidence of most

extensive deposits of coal of a quality superior to any specimen of that

mineral which he had previously seen in British Columbia and Vancouver

Island, and that the land generally seemed excellent and well adapted

for agricultural purposes.

Forty miles north of Port Essington, and 240 from the north end of

Vancouver Island, Fort Simpson is reached, which is situated as nearly

as possible upon the line of boundary between Great Britain and Russia.

This post has been established for many years, and is surrounded

somewhat thickly by Indians, among whom Mr. Duncan; the missionary

teacher, of whose self-denying life and valuable labours I shall

hereafter have occasion to speak at greater length, works with such

singular success.

From the 25th August to the 30th September we were employed among the

inner channels between Nanaimo and Victoria, and in putting down a set

of buoys on the sands at the entrance of the Fraser River. On the

islands in these inner channels there are now several agricultural

settlements, the principal one being on Admiral Island, an island

fourteen miles long by four or five wide, having two or three excellent

harbours, and containing much good land. On this island there are

saltsprings.

Admiral Island is next to Vancouver, from which it is separated by a

narrow strait, called Sausum Narrows, which at its narrowest part is

little more than half-a-mile Avide.

Four miles west of the south part of Admiral Island, Cape Keppel, is

Cowitchin Harbour. As a harbour this is not worth much; but it will be

of importance when the Cowitchin Valley, which runs back from it,

becomes settled. This valley is the most extensive yet discovered on the

island, and is reported by the colonial officers who surveyed it to

contain 30,000 or 40,000 acres of good land. It is peopled by the

Cowitchin tribe of Indians, who, as I have mentioned, are considered a

badly-disposed set, and have shown no favour to those settlers who have

visited them valley. Although it has been surveyed it cannot yet be

settled, as the Indians are unwilling to sell, still less to be ousted

from their land. Through this valley runs the Cowitchin River, which

comes from a large lake of the same name, and 24 miles inland, and

empties itself into the head of Cowitchin Harbour. It is navigable for

several miles for canoes. Between Cowitchin and Nanaimo there is a

considerable quantity of good land, Avhicli has been surveyed and is

called the Chemanos district.

Immediately south of Cowitchin Harbour is the Saanich Inlet, a deep

indentation running 14 miles in a south-south-east direction, carrying

deep water to 'its head, and terminating in a narrow creek within four

miles of Esquimalt Harbour. This inlet forms a peninsula of the

south-east portion of Vancouver Island of about 20 miles in a

north-north-wesl and south-south-east direction, and varying in breadth

from eight miles at its southern part to three at its northern. On the

southern coast of this peninsula are the harbours of Esquimalt and

Victoria, in the neighbourhood of which for some five miles the country

is pretty thickly wooded—its prevailing features lake and mountain—with,

however, some considerable tracts of clear and fertile land. The

northern portion for about ten miles contains some of the best

agricultural land in Vancouver Island. The coast here, as everywhere

else, is fringed with pine; but in the centre it is clear prairie or

oak-land, most of it now under cultivation. Seams of coal have also been

found here. On the eastern or peninsular side of the inlet are some good

anchorages, the centre being for the most part deep. A mile and a half

from the head of the inlet is a large lake, called Langford Lake, which

is very likely to be called into requisition some day to supply the

ships in Esquimalt Harbour, from which it is two miles and a half

distant, with water. Outside the Saanich peninsula is Cordova Channel,

extending to Discovery Island, seven miles from Victoria. Like all these

inner passages, this one is quite safe for steamers, but, from the

varying currents, dangerous for sailing vessels. As several farms have

been established along the shore of the island here, looking out on the

Haro Strait, and the land is much more clear than usual, this is one of

the prettiest parts of the island.

On the 30th September the Admiral (Sir R. L. Baynes, K.C.B.), came on

board, and we took him to Nanaimo and Burrard Inlet, returning to

Esquimalt on the 4th October. From this time until the 28th we continued

working northward from Nanaimo, when, having been drenched to the skin

nearly every day for a month, the captain determined to close the

season’s operations, and we made for Nanaimo. Here we found—what was not

unfrequently the case—that the Indians were all more or less drunk,

owing to a grand feast which had been given by the chief of the tribe a

few days before, and that they would not get the coal out of the pit for

us: we had, therefore, to help ourselves.

On the 10th of February, 1860, having brought our winter duties to an

end, we started for San Francisco, and anchored that night in Neali Bay,

of which I have spoken in describing the Strait of Fuca. Next morning we

proceeded out of the Strait, passing several vessels on their way in.

The sight of these vessels could scarcely fail to remind us of the

colony which had sprung into existence since we had rounded Cape

Flattery and entered that Strait three years before, when we might have

steamed up and down it for a week without meeting more than a few

vessels, and those bound to American ports. In the passage between San

Francisco and Vancouver Island there is nothing worthy of particular

notice, except the change from the everlasting pine-trees which friDge

all our shore, to the almost treeless coast of California. One cannot

help feeling that Nature has been unfair in its distribution of timber

in these regions. California, comparatively speaking, may be said to

have none, all their plank being supplied from the saw-mills before

spoken of as being at work in Puget Sound and Admiralty Inlet. It was

with considerable difficulty and at great expense that they managed to

get sufficient wood to build a small steamer, ordered by the Federal

Government to be constructed at Mare Island, the dockyard of San

Francisco. The coast all the way down is well lighted, but there are no

good harbours; San Francisco, indeed, is the only good one between the

Strait of Fuca and Acapulco, which is 1500 miles below it, on the coast

of Mexico, although there are several open anchorages. The distance from

Cape Flattery to the Golden Gate, as the entrance of San Francisco

harbour is called, is 700 miles, and the mail-steamers make the passage

generally in three days and a half to five days. We, however, were under

sail much of our time, and did not make it until seven days after

leaving Esquimalt. On the morning of the 17th we sighted the noble head,

the name of which has been changed from “Punta de Los Reyes”—the grand

name the old Spaniards had given it—to “Point Reyes”—and crossing the

bar, entered the harbour at four in the afternoon. .

Nothing can be finer than the entrance to this magnificent harbour; and,

considering also the country of which it is the only port, its name of

“Golden Gate” is very appropriate, although the name was given to it

long before the discovery of gold in California. It had reference, no

doubt, to the beauty of the country generally, and to the golden

appearance it wears in spring, before the parching summer sun has

scorched its verdure.

Fifteen miles off the harbour is a group of rocky islands, called the

Farrallones, on the southern of which is a lighthouse. Off the entrance

of the harbour is the “Bar,” on which the surf is generally rough. This

bar, however, serves to let the mariner know he is off the entrance if

he is trying to make the harbour in a fog; which, as they prevail

constantly from May till October, he is very likely to do. The current

in the entrance varies from two to five knots. There are two lighthouses

at the mouth of the harbour, and on the hill above, on each side, is a

telegraph-station. The constant fogs make this of little use, as ships

are always slipping in and out without their arrival or departure being

known. When we went in H.M.S. ‘ Hecate/ in October, 1861, nobody knew

anything of our arrival till some of the officers appeared at the club.

Generally speaking, however, vessels arriving are seen as they pass

Alcatraz Island, which lies in the middle of the harbour, and is a

military station. Although some attempt has been made to fortify San

Francisco, it is still very imperfect in this respect. The only

defensive works as yet existing are, a brick fort on the south side of

the entrance, intended to carry 140 guns, in three tiers of casemates,

and one tier en barbette. A battery, intended to mount eleven heavy

guns, is being constructed on the hill above this fort. Alcatraz Island,

in the middle of the harbour, is partially fortified; and as the guns on

this island are 150 feet above the sea, it would be an awkward place to

attack with ships. This island is about three miles and a half from Fort

Point; it is a small place, about 550 yards long, by 150 yards wide.

Their guns are all en barbette, and number about 100. There is no water

on the island, and they have to supply it from Saucehto Bay, five or six

miles distant, and keep it in a large tank, said to hold 50,000 gallons.

I had last visited San Francisco in 1849, when the gold-fever was at its

height, and there were only a dozen houses in the place, the 5000 or

6000 inhabitants being scattered about in tents. At that time the site

of the present magnificent city was a bare sand-hill. In those days the

harbour was filled with merchant-ships, as now; but although they

entered in great numbers, few went out, both officers and men deserting

the ships for the diggings as soon as the anchors were let go, and

leaving their cargoes to be unloaded by others. Where these vessels used

then to be anchored fine streets have been erected, for all the lower

part of San Francisco is built out over the harbour. Many accidents are

constantly occurring from the insecure way in which these streets are

left. It is dangerous to go down to the wharves after dark, from the

large holes left exposed, through which many poor fellows have fallen

and been killed. Constant actions are being brought against the Town

Council on this account. Greenhow, the American historian, was killed by

falling through one of these places, and his widow brought an action

against the Town Council, recovering the sum of 10,000 dollars for her

loss.

San Francisco has been twice burnt down in the twelve years during which

it has been in existence. These fires have been most beneficial to the

town, as most of the wooden buildings which were destroyed have been

replaced by very fine brick ones. Montgomery Street, the principal

thoroughfare in the town, is now almost as fine a street as any European

capital can boast of; equal, indeed, in the size of the buildings and

magnificence of the shops, to the best thoroughfares of London. No city

in the world has, I imagine, a history so short and wonderful as San

Francisco. In February, 1849, the population was about 2000: in the

middle of the same year it had risen to 5000; while it is stated that

from April, 1849, to January, 1850, nearly 40,000 emigrants arrived, of

which only 1500 were women. By the year 1860, the population had risen

to 66,000. In addition to these, thousands went to the mines direct,

many crossing the continent and the Sierra Nevada, where hundreds left

their bones to bleach among the mountains.

Among the thousands who hurried to California from every part of the

world, it may be imagined there were many of the very dregs of society.

Convicted felons from our penal colonies—every one, indeed, whose own

country was too hot for him, hastened hither. Murders, incendiarisms,

and every kind of crime were being daily perpetrated; no decent man

dared to walk the streets after dark, and no property was safe. Law

there was not; and where two-thirds of the population were scoundrels,

it may be imagined what class of public officials would be elected under

the system of universal suffrage. What, therefore, between the weakness

or partiality of the judges, the technicalities of the law, the

dishonesty of the juries, and the dread of witnesses to tender their

evidence, San Francisco, in 1851, was suffering from anarchy

unparalleled in modern history. It was this social condition of the city

that caused the organisation of that most remarkable society, the

“Vigilance Committee,” to which I have had occasion to allude in a

former chapter.

This association was formed in June, 1851, “for the protection of the

lives and property of citizens resident in the city of San Francisco.” A

council was appointed and a place of meeting fixed, while the tolling of

the bell of the Monumental Fire Engine Company was the signal for

assembly. Although the “Vigilance Committee” has for several years now

allowed the law of the land to take its course, it still exists, and is

ready to assemble whenever the signal may be given. “What has become of

your Vigilance Committee,” I asked one of them when I was in San

Francisco in October last. “Toll the bell, Sir, and you will see,” was

the reply. “Oh, then you are still under orders?” “Always ready at the

signal, Sir. If it were now given, you would see thousands at the

meeting-place before the bell had ceased to sound.”

There is no doubt that this strange organisation exercised, and still

exercises, a most wholesome restraint over a society that, but a few

years since, elected a miner to be chief judge of the State, and whose

two principal judges now go by the significant sobriquets of “Mammon”

and “Gammon.” The first proceeding of the committee in the summer of

1851 was to arrest, try, and hang four men, three of whom confessed

their crimes, while the fourth was, I believe, undoubtedly guilty. The

moral effect of this proceeding was wonderful. All the other towns,

which were rising all over the State, formed Vigilance Committees of

their own. Many known ruffians, whose crimes could not be brought home

to them, were ordered to leave the State; while others were kept in

surveillance, and reported from Committee to Committee as they traversed

the country. For years after this California was almost free of crime.

Although by the greater number of the people the Vigilance Committee was

held in favour, the officials and some others denounced it, and to this

day stigmatise its existence as a disgrace to California. These termed

themselves the “Law and Order ” party; but upon many occasions their

weakness to restrain the mixed and dangerous population of San Francisco

was made apparent.

I have entered more fully into the history of San Francisco than I

otherwise should have done, since I think a valuable and fair comparison

may be drawn between these scenes and the peaceable course of British

Columbia since the discovery of gold there five years ago. The reader

unacquainted with the past history of California, would scarcely credit

the fearful scenes through which she has reached her present growth.

If San Francisco were

the only city in California, its dimensions would not, perhaps, be so

surprising; but it is only one of many, almost as large and equally

beautiful, in the State. Sacramento, the seat of government, Stockton,

and others, vie with it in size, while Marysville, Benicia, Los Angelos,

&c., are far more beautifully situated.

After a few days’ stay off San Francisco, we proceeded to Mare Island,

where the Government dockyard is established. Mare Island is 23 miles

from San Francisco, across San Pablo Bay, and at the mouth of the

Sacramento. Here we were received by the American naval officers, and

immediately put on the dock.

It may be interesting to some of my readers if I here say something of a

Sectional Dock, such as that we were now placed upon, and which, though

generally used in America, is very little known, and still less liked,

in this country. In a new country where there is plenty of timber, this

kind of dock has one great advantage, in its cheapness and facility of

construction, compared with the ordinary stone docks. But in California,

where, as I have before said, there is very little timber, a stone dock

might have been constructed almost as cheaply. The dock of which I am

speaking had to be built at Pensacola, and then taken to pieces, and

sent out to California at an expense, I was there told, of about 70,000

dollars (15,000l.)

The Sectional Dock is composed of a series of sections, or iron tanks,

each being fitted with a complete pumping-apparatus, elevated on a

framework 60 or 80 feet above the top of the tank. These tanks are

fitted with gates, like the caissons used in English docks, so that they

can be filled, sunk, or again puruped out at pleasure. A number of these

sections, varying according to the weight and length of the ship to be

lifted, are securely chained together, and the whole is moored in water

sufficiently deep to allow of their being sunk beneath the vessel’s

keel. They are generally kept level with the water’s edge; but when a

vessel is to be docked, they are sunk low enough to allow her to come

over the blocks which are placed along the centre. The vessel is then

hauled over the blocks, the pumps started, and, as she rises, shores

from the sides of the tanks, and from the frames of the pump-houses, are

placed under her and against her sides, and she is gradually raised till

her keel is out of the water. If proper care is taken, these docks are

quite safe, but the ship must be placed cautiously on the blocks, or an

accident is very likely to happen. In 1860 H.M.S. ‘Termagant’ was

allowed to fall over in this dock, and was for some time in great

danger. Her stern was allowed to rest on the edge of one of the

sections, which, as her weight came upon it, rose up and turned over.

This canted the ship, and she fell with her masts against the

pump-houses. Fortunately she had only been raised a little way; had she

been further out of the water, she would probably have broken down the

pump-houses, and very likely sunk. One advantage possessed by these

docks is, that the ship being, as it were, raised into the air, there is

better light for working at her bottom than in a stone dock.

While at San Francisco we had, of course, many opportunities of

remarking those peculiar habits of manner and phraseology indulged in by

the Americans. At Victoria, peopled as it is by Americans, we had been

made familiar with them; but here they were more commonly and glaringly

used. Certainly, they justify anything that Mr. Dickens or other English

satirists have written of them. Americans all say—not, however, with

perfect truth—that these eccentricities belong only to the lower orders

of society. I have the pleasure of knowing both American gentlemen and

ladies quite free from their use; but still I have met many others,

holding good positions in society, thoroughly “Yankee” in tone and

expression. These Americanisms must lose much of their ludicrous effect

by being written, as it is impossible to give the tone and peculiar

emphasis of the speaker. Words are often used by them to convey a sense

entirely different to that which we apply to them. Thus, “I’ll happen in

directly” is considered rather a good expression for a contemplated

visit. So, “clever” does not imply any talent in the individual of whom

it is spoken, but is said of a good-natured, gentlemanly man generally;

while “smart” answers for our “clever.” Speaking to an American naval

officer, just before leaving Victoria for San Francisco, he said, “Well,

sir, I guess you’ll have quite an elegant time down there. Elegant

place, sir, San Francisco.” A very pretty young lady, living in Puget

Sound, and happening to be on board the ‘Plumper,’ said to one of the

officers: “Well, sir, if you come over to Steilacoom, I guess you shall

have a tall horseback rideby which form of expression she meant to

imply, not that the horse should be longer in the legs than is usual,

but that care should be taken that the ride should be more than

ordinarily agreeable. In a book on Americanisms, published last year, a

Baltimore young lady is represented as jumping up from her seat on being

asked to dance, and saying, “Yes, sirree; for I have sot, and sot, and

sot, till I’ve nigh tuk root!” I cannot say I have heard anything quite

equal to this; but I very well remember that at a party given on board

one of the ships at Esquimalt, a young lady declined to dance a “fancy”

dance, upon the plea, “I’d rather not, sir; I guess I’m not fixed up for

waltzing—an expression the particular meaning of which must be left to

readers of her own sex to decide. An English young lady, who was staying

at one of the houses at Mare Island, when we were there, happened one

evening, when we were visiting her friends, to be confined to her room

with a headache. Upon our arrival, the young daughter of our host—a girl

of about twelve—went lip to her to try to persuade her to come down.

“Well,” she said, “I’m real sorry you’re so poorly. You’d better come,

for there are some almighty swells down there!” A lady, speaking of the

same person, said, “Her hair, sir, took my fancy right away.” Again,

several of us were one day talking to a tall, slight young lady about

the then new-fashioned crinoline which she was wearing. After a little

banter, she said, “I guess, Captain, if you were to take my hoops off,

you might draw me through the eye of a needle!”

Perhaps one of the most whimsical of these curiosities of expression,

combining freedom of manner with that of speech, was made use of to

Captain Richards by a master-caulker. He had been vainly endeavouring to

persuade the Captain that the ship required caulking, and at last he

said in disgust, “You may be liberal as a private citizen, Captain, but

you’re mean to an almighty pump-tack! ”—in his official capacity, of

course. Again, an American gentleman on board one of our mail packets

was trying to recall to the recollection of the mail agent a lady who

had been fellow-passenger with them on a former occasion. “ She sat

opposite you at table all the voyage,” he said. “Oh, I think I remember

her; she ate a great deal, did she not?” “Eat, sir!” was the reply, “she

was a perfect gastronomic filibuster!” One more example, and I have done

with a subject upon which I might enlarge for pages. The boys at the

school at Victoria were being-examined in Scripture, and the question

was asked, “In what way did Hiram assist Solomon in the building of the

Temple?” It passed two or three boys, when at last one sharp little

fellow triumphantly exclaimed, “Please, sir, he donated him the lumber.”

Hardly less remarkable than their peculiarities of language is their

habit of taking drinks with remarkable names from morning till night. No

bargain can be made, no friendship cemented—in fact, no meeting can take

place—without “liquoring up.” The morning is commenced with a brandy, or

champagne, cocktail, not infrequently taken in bed. This is continued,

at short intervals, until bedtime again, and no excuse will avail you

unless you can say you are a “dashaway,” which is their name for a total

abstainer. This habit, I must say, does not extend so high in the social

scale as the other; it is, however, the great social failing of the

Western States.

The repairs of the ship were finished, and on the 9th March we left San

Francisco to return to our work; little thinking that in scarcely more

than a year we should revisit it again with another ship in a worse

state than we had brought the ‘Plumper.’ |