|

False Report.-Souzie's

farewell. - St. Albert Mission.-Bishop Grandin.- Small pox.-Great

Mortality. — Indian Orphans. — The Sisters of Charity. — Road to Lake St.

Ann's.—Luxuriant Vegetation.—Pelican.—Early frosts.—Paok horses—Leaving

St. Ann's. — Indians. — Vapour Booths. — Thick woods. — Pembina River. —

Coal.— Lobstick Camp.—Condemned dogs.—Beaver dams.—Murder.—Horse lost.—A

Birthday.—No trail.—Muskegs.—Windfalls.—Beavers.—Traces of old travellers.—Cooking

pemmican. — Crossing the McLeod. — Wretched Road. — Iroquois Indians. —

Slow progress.—Merits of pemmican.—Bad Muskegs.—Un beau chemin.—A mile an

hour. —Plum-pudding Camp. — Ten hours in the saddle. — Athabasca

River.—The Rooky Mountains.—Bayonet Camp.

August 28th.—It is

proverbially difficult to get away in a hurry from an Hudson's Bay Fort,

especially if outfit is required; but, we were furthered, not only by the

genuine kindness of Mr. Hardisty but by a false alarm that quickened every

one's movements, and so we got off early in the afternoon.

A foolish report reached

Edmonton in the forenoon, that the Crees and Blackfeet were fighting on

the other side of the river, a report based, as we afterwards learned, on

no other ground than that 'some one' had heard shots fired, at wild duck

probably enough. Where there are no newspapers to ferret out and

communicate the truth to every one, it is extraordinary what wild stories

are circulated; and how readily they are believed, though similar 'on dits'

have been found to be lies time and again. As we would be detained with

long pow-wows, if either party crossed the river, every one helped us to

hurry off. We had to say "good bye" not only to the Indians who had come

from Fort Pitt, and to Mr. McDougal and the gentlemen of the Fort; but

also to Horetsky and to our Botanist, as the Chief had decided to send

these two on a separate expedition to Peace River, by Fort Dunvegan, to

report on the flora of that country, and on the nature of the northern

passes through the Rocky Mountains. We parted with regret, for men get

better acquainted with each other on shipboard, or in a month's travel in

a lone-land, than they would under ordinary circumstances in a year.

Souzie was more sorry to part with Frank than with any of the rest of us.

He had been teaching him Cree, and Frank had got the length of twenty-four

words which he aired on every possible occasion, to his tutor's unbounded

delight. Souzie mounted his horse and waited patiently at the gate of the

Fort for two hours, without our knowledge. When Frank came out he rode on

with him for a mile to the height of a long slope; then he drew up and

putting one hand on his heart, with a sorrowful look, held out the other;

and, without a word, turned his horse and rode slowly away.

Our number was now reduced to four. We were to

drive out fifty miles to Lake St. Ann's, and "pack" our travelling stores

and baggage on horses there ; taking with us the faithful Terry as cook,

and three new men; a guide and two packers. Mr. Hardisty kindly

accompanied us ten miles out, to the guard at Lake St. Albert, to see that

we got good horses. The road is an excellent one, and passes through a

rolling prairie, dotted with a great number of dried marshes on each side,

from which immense quantities of natural hay could be cut.

Crossing the same Sturgeon River that we had

crossed yesterday morning on our way to Edmonton, a hill rose before us

crowned with the Cathedral Church of the Mission, the house of the Bishop,

and the house of the Sisters of Charity ; while, up and down the river

extended the little houses and farms of the settlers. We called on Bishop

Grandin and found him at home, with six or seven of his clergy who

fortunately happened to be in from various missions. The Bishop is from

old France. The majority of the priests, and all the sisters, are French

Canadians. The Bishop and his staff received us with a hearty welcome,

showed us round the church, the school, the garden, and introduced us to

the sisters. The church represents an extraordinary amount of labour and

ingenuity, when it is considered that there is not a saw mill in the

country and that every plank had to be made with a whip or hand saw. The

altar is a beautiful piece of wood-work in the early Norman style,

executed as a labour of love by two of the fathers. The sacristy behind,

was the original log church and is still used for service in the winter.

This St. Albert mission was formed about nine

years ago, by a number of settlers removing from Lake St. Ann's in hope of

escaping the frosts which had several times cut down their grain there. It

grew rapidly, chiefly from St. Ann's and Red River, till two years ago,

when it numbered nearly one thousand, all French half-breeds. Then came

the small-pox that raged in every Indian camp, and, wherever men were

assembled, all up and down the Saskatchewan. Three hundred died at St.

Albert. Men and women fled from their nearest and dearest. The priests and

the sisters toiled with that devotedness that is a matter of course with

them; nursed the sick, shrived the dying, and gathered many of the orphans

into their house. The scourge passed away, but the infant settlement had

received a severe blow from which it is only beginning to recover. Many

are the discouragements, material and moral, of the fathers in their

labours, as they frankly confessed. Their congregation is migratory,

spends half the year at home and the other half on the plains. The

children are only sent to school when there are no buffalo to hunt, no

pemmican to make, or no work of greater importance than education to set

them at. The half-breed is religious, but he must indulge his passions. It

is a singular fact that not one of them has ever become a priest, though

several, Louis Riel among the number, have been educated at different

missions, with a view to the sacred office. The yoke of celibacy is too

heavy; and fiddling, dancing, hunting, and a wild roving life have too

many charms. The

settlement now numbers seven hundred souls. The land is good, but, on

account of its elevation, and other local causes, subject to summer

frosts; in spite of these, cereals, as well as root crops, succeed when

any care is taken. Last year they reaped on the mission farm twenty

returns of wheat, eighteen of barley, sixteen of potatoes. Turnips, beets,

carrots and such like vegetables, grow to an enormous size. A serious

drawback to the people is that they have no grist mill; the Fathers could

not get them to give up the buffalo for a summer and build one on the

Sturgeon. They would begin it in the fall and finish it in the spring; but

the floods swept it away half-finished, and the Fathers have no funds to

try anything on a solid and extensive scale.

The sisters took us to see their orphanage.

They have twenty-four children in it, chiefly girls; two-thirds of the

number half-breeds, the rest Blackfeet or Crees who have been picked up in

tents beside their dead parents, abandoned by the tribe when stricken with

small-pox. The hair of the Indian boys and girls was brown as often as

black, and their complexions were as light as those of the half-breeds.

This would be the case with the men and women also, if they adopted

civilized habits. Sleeping in the open air, with face often turned upward

to a blazing sun, would soon blacken the skin of the fairest European.

Last Sunday we noticed, in the congregation at Victoria, that while some

of the old Indians had skins almost as black as negroes, the young men and

women were comparatively fair. The simple explanation is that the young

Crees are taking now to civilized ways. People at Fort Garry told us that

when the troops arrived under Colonel Wolsely, some of them, who had slept

or rowed the boats bare-headed under the blazing sun, were quite as

dark-complexioned as average Indians. The gentle Christian courtesy and

lady-like manners of the sisters at the mission charmed us, while the

knowledge of the devoted lives they lead must impress, with profound

respect, Protestant and Roman Catholic alike. Each one would have adorned

a home of her own, but she had given up all for the sake of her Lord and

His little ones. After being entertained by the bishop to an excellent

supper, and hearing the orphans sing, we were obliged to hurry away in

order to camp before dark. The Doctor, however, remained behind for an

hour to visit three or four who were sick in their rooms, and arrange

their dispensary. Taking leave of Mr. Hardisty also, we drove on three

miles farther and camped. Five of us occupied one tent; our own party of

four and Mr. Adams, the H. B. agent at Lake St. Ann's who was returning

from Edmonton to his post.

August 29th.—Some of the horses were missing

this morning, but an hour after sunrise all were found except Mr. Adams'

and another, whose tracks were seen going in the St. Ann's or homeward

direction. Knowing that we would overtake them the start was made. After a

third and fourth crossing of the Sturgeon river, we halted for breakfast.

We then crossed it for the fifth and last time, caught up to the two

horses quietly feeding near the wayside, dined at mid-day, and rode on in

advance with Mr. Adams to St. Ann's, leaving the two carts to follow more

leisurely. We reached the post an hour before sunset, having ridden nearly

forty miles, though, as we had presented the odometer to Mr. McDougal, our

calculations of distances were now necessarily only guess work. The carts

got in an hour after, and the tent was pitched and the carts emptied for

the last time. From St. Ann's the road is only a horse-trail through the

woods, so often lost in marshes or hidden by windfalls that a guide is

required. Tents, for the sake of carrying as little weight as possible,

were discarded for the simple "lean to"; and wheels had to be discarded

for pack horses. Our guide was Valad, a three-quarters-Indian, and our

packers—Brown a Scotchman, and Beaupré a French Canadian ; both old

packers and miners and first rate men. They said that the whole of next

day would be required to arrange the pack-saddles, but they were told that

we must get away from the post immediately after dinner, so that one

"spell" might be made on the 30th, and a long day on the 31st. The road

travelled over to-day was through a beautiful country, hilly and wooded,

creeks winding round narrow valleys and others that beaver dams had

converted into marshes, on which were growing great masses of natural hay,

that there was no one to cut. The vegetation on the hill-sides was most

luxuriant. The grass reached to the horses' necks, and the vetches, which

the horses snatched at greedily as they trotted past, were from four to

six feet high. The last twelve miles of the day's journey resembled a

pleasure drive; the first half amid tall woods through which the sunlight

glimmered, with rich green underbrush of wild currant, mooseberry, and

Indian pear, the ripe fruit of which we plucked from our saddles. Through

these our road led down to the very brink of Lake St. Ann's, a beautiful

sheet of water, stretching away before us for miles, enlivened with flocks

of wild duck and pelican on the islets and promontories that fringed it;

and then round the south west-side of the lake, for the last six miles, to

Mr. Adams' house. Mrs. Adams had a grand supper ready for us in half an

hour, and we did full justice to the cream and butter, and the delicious

white-fish of Lake St. Ann's. This fish (albus coregonus) is in size and

shape and even taste very like the shad of the Bay of Fundy; but very

unlike it in the number and intricacy of its bones. It is an infinite toil

to eat shad ; and with all possible care little prickly bones escape

notice and insinuate themselves into the throat; but with white-fish a man

may abandon himself to the simple pleasure of eating. Lake St. Ann's is

the great storehouse of white-fish for supplying this part of the country.

It provides for all demands up to Edmonton, Last year thirty thousand,

averaging over three pounds each, were taken out and frozen for winter

use. This was the

worst place for summer frosts that we had yet seen. A field of potatoes

belonging to the priest was cut down to the ground, and Mr. Adams pointed

out barley that had been nipped two or three times, but from which he

still expected half a crop.

August 30th.—"Packing" the horses was the

order of the day till two o'clock, and Brown and Beaupré showed themselves

experts at the work. A pack-saddle looks something like a miniature wooden

"horse" such as we have all seen used in our backyards for sawing sticks

of cordwood. Wooden pads suited to the shape of the horse's back, with two

or three plies of buffalo robe or blanket underneath, prevent the cross

legs and packs from hurting the horse. All the baggage, blankets,

provisions, and utensils are made up into portable bundles as nearly equal

in size and weight as possible. Each of the packers seizing a bundle

places it on the side of the saddle, another bundle is put on the top

between the two, where the log of wood to be sawed would be placed, and

then the triangular shaped load is bound in one by folds of shaganappi

twisted firmly but without a knot, after a regular fashion called the

"diamond hitch." The

articles which experience had shown to be not indispensable or not

required for the mountains, were now discarded, and other things of

exactly the right sort obtained in their stead; the object being to give

as light loads as possible to the horses, that they might travel the

faster. A horse with a hundred weight on his back can trot without racking

himself: when he has from one hundred and sixty to two hundred pounds he

can only walk, not only because of the weight but because the load catches

in the bushes and between trees and rocks, and jars him constantly. If the

horse is at all restive and breaks from the path, he crashes through dead

wood and twists through dry till he destroys the load, or is brought up

all standing by trees that there is no getting through.

In the Mexican and United States Rocky

Mountains, where a great deal of business has long been done with

pack-horses, the saddles are of a much superior kind, called appara-hoes.

With those the horses carry over three hundred pounds, and a day's journey

is from twelve to fifteen miles. As our object was speed we dispensed with

tent, extra clothing, tinned meat, books etc., and thus reduced the loads

at the outset to a hundred or a hundred and thirty pounds per horse. That

weight included food for thirty days for eight men, and everything else

that was absolutely necessary.

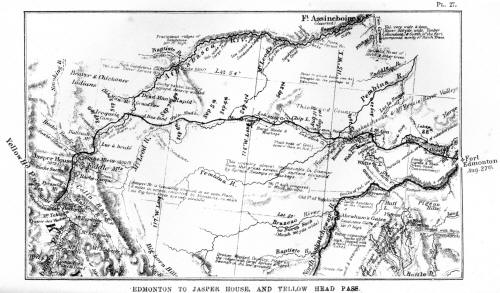

There was now before us a journey of about six

hundred miles, through woods and marshes, torrents, and mountain passes;

for we could not depend on getting supplies of any kind or fresh horses on

this side of Kamloops; though there were probabilities of our meeting with

parties of engineers between Jasper House and Yellow Head Pass.

Mr. Adams was of infinite service in all these

arrangements. The luxuries of white-fish, fresh eggs, cream, butter and

young pig bountifully served up for us at his table, were duly appreciated

at breakfast and dinner, but we valued still more highly the personal

exertions, made as earnestly and with as much simplicity and

thoughtfulness as if he had been preparing for his own journey. He was the

last of the Hudson's Bay officers that we would be indebted to till we got

to the Pacific slope, and parting from his post was like parting from the

Company that has long been the mainstay of travellers, the only possible

medium of communication, and the great representative of civilization in

the vast regions of the North and North-west. From our meeting with the

chief Commissioner at Silver Heights until our departure from St. Ann's we

had experienced the hospitality of its agents, and had seen the same

extended to all who claimed it, to the hungry Indian, and the unfortunate

miner, as well as to those who bore letters of recommendation. It was on

such a scale as befitted a great English corporation, the old monarchs and

still the greatest power in the country.

At two P. M. all was ready; eight horses

packed, eight others saddled for riding, and a spare horse to follow. Mr.

Adams accompanied us a short distance ; but, as the line of march had to

be Indian file, we soon exchanged the undemonstrative "good-bye" with him,

and plunged into the forest. For the first five miles the trail was so

good that the horses kept at their accustomed jog-trot, though some of

them were evidently unused to, and uneasy under their pack-saddles. Valad

rode first, two pack-horses followed, Brown next, and so on till the Chief

or some other of the party brought up the rear of the long line on the

seventeenth horse. If any of the pack-horses deviated from the road into

the bush, the man immediately behind had to bring him back. The loud calls

to the obstinately lazy or straying "Rouge," "Brun," "Sangri," "Billy," "Bischo,"

varied with whacks almost as loud on their backs, were the only sounds

that broke the stillness of the forest; for conversation is impossible

with a man on horse-back in front of or behind you, and there is little

game in these woods except an occasional partridge. After the first day,

the horses gave little trouble as they all got accustomed to the style of

travelling, and recognized the wisdom of keeping to the road. Two or three

old hands at the work always aimed at getting one of their companions

between them and a driver, so that their companions might receive all the

occasional whacks, and they share the benefit only of the loud calls and

objurgations; but the new ones soon got up to the trick, and their

contentions for precedence and place were as keen as between a number of

old dowagers before going in to dinner. These old hands carried their

burdens with a swinging, waddling motion that eased their backs, and saved

them many a rude jar.

In the course of the afternoon we passed one

or two deserted tents, and "sweating booths," but no Indians. Three

miserable starved looking "Stonies" or Wood Indians had entered Mr. Adams'

house while we were there, and, in accordance with invariable Indian

etiquette, shook hands all round, before squatting on the kitchen floor

and waiting for something to eat; but, with the exception of the few

scattered round each of the Company's posts, who as a rule are invalids or

idlers, we had not seen an Indian since leaving the Assiniboine, except

the small camp near Moose-Creek and the Crees at Victoria. That they were

buffalo hunting or that their principal settlements are off the line of

the main road, does not give the whole truth. The Indians are evidently

decreasing; "dying out" before the white man. Now that the Hudson's Bay

monopoly is gone, "free traders," chiefly from the south, are coming in,

plentifully supplied with a poisonous stuff, rum in name, but in reality a

compound of tobacco, vitriol, bluestone and water. This is completing the

work that scrofula and epidemics and the causes that bring about scrofula

and epidemics were already doing too surely: for an Indian will part with

horse and gun, blanket and wife for rum. There is law in abundance

forbidding the sale of intoxicating liquor to Indians, but law, without

force to execute law, is laughed at by rowdies from Belly River and

elsewhere. The

"sweating booths" referred to should have been explained before. They are

the great Indian natural luxury, and are to be found all along the road,

or wherever Indians live even for a week. There was scarcely a day this

month that we did not pass the rude slight frames. At first we mistook

them for small tents. They are made in a few minutes of willow wands or

branches, bent so as to form a circular enclosure, with room for one or

two inside; the buffalo robe is spread over the frame work so as to

exclude the air as much as possible, and whoever wants a Russian bath

crawls into the round dark hole. A friend outside then heats some large

stones to the highest point attainable, and passes them and a bucket of

water in. The "insides" pour the water on the stones, steam is generated,

and, on they go pouring water and enjoying the delight of a vapor bath,

till they are almost insensible. Doctor Hector thought the practice an

excellent one, as regards cleanliness, health and pleasure; but the

Indians carry it to an extreme that utterly enervates them. Their

medicine-men enlist it in aid of their superstitions. It is when under the

influence of the bath, that they become inspired; and they take one or two

laymen in with them, that they may hear their oracular sayings, and be

able to announce to the tribe where there is a chance of stealing horses

or of doing some other notable deed with good prospect of success. It is

easy to see, too, what a capital opportunity the medicineman has, when

thus inspired to gratify his private malice or vengeance, or any desire.

Many a raid and many a deed of darkness has been started in the sweating

booth. The first five

miles of the road, this afternoon, was a broad easy trail, through open

woods which showed fine timber of spruce, aspen, and poplar, some of the

spruce being over two feet in diameter ; but had we formed from it any

conclusion as to our probable rate of speed, the next four miles would

have undeceived us. Crashing through windfalls or steering amid thick

woods round them, leading our horses across yielding morasses or stumbling

over roots, and into holes, with all our freshness we scarcely made two

miles an hour, and that with an expenditure of wind and limb that would

soon have exhausted horse and man. But the road again improved a little,

and by 6.30 P.M., we had accomplished about twelve miles, and reached a

lake called "Chain of lakes" or "Lac des Iles," out of which the Sturgeon

river flows before it runs into Lake St. Ann's. In an open ground near the

lake, covered thick with vetches, a simple 'lean to' or screen for the

whole company was constructed. In the morning all decided that the ' lean

to' was a preferable home to the round or closed tents we had hitherto

used. You require for the former only a large cotton sheet in addition to

what the forest supplies at any time. Two pairs of cross-poles are stuck

in the ground, as far apart as you wish your lodging place for the night

to be long; a ridge pole connects these, and then half-a-dozen or more

poles are placed slanting against the ridge pole. Cover the sloping frame

with your cotton sheet, or in its absence, birch bark, and your house is

made. The ends are open and so is the front, but the back is covered, and

that, of course, is where the wind comes from. The ventilation is perfect,

and as your fire is made immediately in front, there is no lack of warmth.

From this date the whole party had one tent of

this description to sleep under, and one table to eat from. The days were

getting shorter, the horses could not go fast, and time therefore had to

be economised in every possible way.

August 31st.—As packing eight horses takes

twice as long as harnessing twice the number, it was 6.30 P.M., before we

started. Hereafter, and for the same reason—the time needed to unpack and

pack,—only one halt and two "spells " per day were to be made.

Six hours' continual travel at an average rate

of three miles an hour, brought us to the Pembina river, where we halted

for two-and-a-half hours. The road was through thick woods and along the

"Chain of lakes," with an upward incline until we came to the watershed

between the Saskatchewan and the rivers running north-east which fall into

the McKenzie, and through it into the Arctic sea. The country then opened,

and we could see before us four or five miles to a ridge, on the other

side of which the guide said was the Pembina. The timber in the morning

was not as large as that nearer St. Ann's; and it became smaller as we

advanced, till in the open it was poor and scrubby, and the land here and

all over the drive to the Pembina looked cold and hungry, with occasional

good spots. In the neighbourhood of coal the land is usually poor, and we

had been told that the banks of the rivers showed abundant indication of

coal for sixty miles up and down from where the trail struck it. After

passing the "Chain of lakes" the road led along a small round lake that

empties on the other side; and, soon after, over a ridge from which a fine

amphitheatre of hills, formed by a bend of the river beneath, opened out

before us, in the valley of which we saw the broad shallow Pembina flowing

away to the north. The underbrush on the hill-sides had decided autumn

tints, the red and yellow showing early frosts, although there would be

nearly three months yet before winter. The top of the opposite bank was a

bold face of sandstone, with what looked like enormous clusters of

swallow's nests running along the upper part; underneath the sandstone,

clay that had been burnt by the spontaneous combustion of the coal

beneath, ash and burnt pieces of shale like red and white pottery on the

surface, half hidden by vegetation; and down at the water's edge a

horizontal bed of coal. We forded the river which is about a hundred yards

wide, and looking back saw on the east side a seam of coal about ten feet

thick, whereas on the west side to which we had crossed only about four

feet showed above the water. Pick in hand the Chief made for the coal, and

finding a large square lump that had been carried down by the river, he

broke some pieces from it to make a fire. In appearance it was much

superior to the Edmonton seam; instead of the dull half-burnt look, it had

a clean glassy fracture like cannel coal. Carrying a number of pieces in

our hands we proceeded to make a fire and had the satisfaction of seeing

them burn, and of cooking our pemmican with the mineral fuel. It was

evidently coal, equal for fuel, we considered, to the inferior Cape Breton

kinds, burning sluggishly, and leaving a considerable quantity of grey and

reddish ash, but giving out a good heat. Beaupré, who all this while had

been washing sand from the river in his shovel for gold, and finding at

the rate of half a cent's worth per shovel full, was amazed at our

eagerness, or that there should have been any doubt about its being coal.

He and his mates when mining on different rivers, had been in the habit of

making fires with it whenever they wished the fire to remain in all night;

and he and Brown both said, that the exposure of coal on Pembina was a

mere nothing compared to that on the Brazeau or North Fork of the North

Saskatchewan; that there were seams eighteen feet thick there; that in one

canyon was a wall of seam on seam as perpendicular as if it had been

plumbed, and so hard that the weather had no effect on it; and that on all

the rivers, for some distance east of Edmonton, and west to the Rocky

Mountains, are abundant showings of coal. This is perhaps the proper place

to mention that on our return to the east, Ex-Governor Archibald presented

the Secretary with a little box full that had been sent him as a sample

from Edmonton ; the sample was exactly like what we picked up in the

Pembina and tried with the results just stated.

The Secretary submitted it to Professor Lawson

of Dalhousie College, Halifax, for analysis, and received a letter of

which the following is an extract, and may be regarded as settling the

question more favourably than we could even have hoped for:

"My analysis of your coal is by no means

discouraging:—

Combustible matter...........97.835 p. c.

Inorganic Ash.............2.165 p.c.

Total 100.000 "The

proportion of sulphur, chlorine, and other obnoxious impurities,

"is quite small. The coal burns with a flame, and also forms a red cinder,

"but is a slow burner; and, although the absolute amount of ash is so

"small, yet a much larger amount of apparent ash will be left in the grate

"from imperfect combustion. Yet, if we view this as a surface sample—

"and such are invariably of inferior quality,—I think it offers great en-

"couragement, for the percentage of ash is less than the average of the

"best marketable coals in Britain. Of course this analysis of a very small

"sample can only be regarded as a probable indication, not a demonstra-

"tion, of the nature of the extensive beds of coal or bituminous shale

"described in your letter."

The simple fact is that the coal deposits of

the North-west are so enormous in quantity that people were unwilling to

believe that the quality could be good.

Here then is fuel for the future inhabitants

of the plains, near water communication for forwarding it in different

directions. Captain

Palliser also reports the existence of iron ore near several coal seams.

After dinner we rode on for three and a half

hours to a good camping ground on the Lobstick river, about eleven miles

from the Pembina; and had the horses watered and everything made snug for

Sunday before sunset.

On the way several creeks had to be crossed,

or valleys where creeks had run till beavers dammed them up, and, as all

had high steep banks, the work was heavy on the horses. But the road so

far had agreeably disappointed us. It was not at all so bad as travellers'

tales had represented. True, it is better at this season of the year and

for the next six weeks, than at any time except in the winter; but we felt

confident that in another week Jasper House would not be far off, unless

the roads became very much worse, instead of fifteen days being required

as every one at Edmonton and St. Ann's had said. So, after a talk with

Brown and Beaupré about their mining and Blackfeet experiences, we threw

ourselves down on a fragrant grassy bed, a little tired, but in good

spirits and glad enough that we were not to be called early in the

morning. September

1st.—When we looked out at our wide open door, between six and seven

o'clock, a good fire was blazing, and by it sat Valad smoking. He might

have been sitting there for centuries, so perfect was the repose of form

and feature. Brown

enquired if he had seen the horses and the answer was a wave of the hand,

first in one direction and then in another, not only enough to say that he

had, but also where they were, without disturbing any of us who might be

asleep. He looked

more like a dignified Italian gentleman than an obscure Indian guide. With

the lazy movements peculiar to Sunday morning in a camp, one after another

of his bed-fellows shook himself out of his blanket. We had now time to

look around, and see what kind of a place we were camping on. A bluff had

stopped the course of the stream on its way east, and made it swing round

to the south. On the bluff, just at the elbow, our tent was pitched. A

rich grassy intervale along the river, and vetches in a little valley on

the other side of our camp, gave good feed for the horses. On the opposite

bank of the stream, and a little ahead, stood three "lobstick" spruce

trees in a clump. From these probably the stream gets its name. A lobstick

is the Indian or half-breed monument to a friend or to a man he delights

to honour. Selecting a tall spruce or some other conspicuous tree, he cuts

off all the middle branches leaving the head and feet of the tree clothed

and the body naked, and then writes your name or initials at the root.

That is your lobstick and you are expected to feel highly flattered, and

to make a handsome present in return to the noble fellow or fellows who

have erected such a pillar in your honour.

There is an old superstition that your health

and length of days will correspond to your lobstick's. As this belief

proved inconvenient in some cases it has been quietly dropped, but the

custom still flourishes and is greatly favoured by the half-breeds.

Whether such a simple way of getting up a

monument is not preferable to piling brick upon brick to the height of a

tree, to show how highly you honour a hero, is a question that might bear

discussion. At

morning service the whole party attended. We did not ask any of the men

"what denomination he was of," but took it for granted that he could join

in common prayer, and hear with profit the simplest truths of

Christianity. With none of our former crews had we been on such friendly

terms as with this one. All the men were up to their work, prompt and

respectful, but the relation seemed more like that of a family than simply

master and servant.

The weather was beautiful as usual. Last night it clouded up and in the

early morning there was a light drizzle of rain, but not enough to wet the

grass as much if there had been the ordinary heavy dew of a clear night.

The forenoon was cool enough to keep the black flies away, but they came

out with the sun and the mosquitoes in the afternoon. At sunset the black

flies vanish, but the mosquitoes keep buzzing round till the night is

sufficiently cold to drive them off to the woods; this usually happens

about nine o'clock. Warm as the days now were the nights were so cold,

though there was no actual frost, that we usually kept our clothes on, in

addition to the double blanket. Our bag or boots served for pillow, and

none of us were ever troubled with wakefulness, or complained in the

morning that there had been a crumpled rose leaf under blanket or pillow.

There was little to mark this Sunday except

the pleasant peaceful enjoyment of it. The murmuring of the river over its

pebbly bed was the only sound that broke the Sabbath stillness. The rest

was peculiarly grateful after the week's hurry and changes; and the horses

looked as well pleased with it as we. They ate till they could eat no

more: and then they affectionately switched or licked the flies off one

another, or strolled up to the camp to get into the smoke of the fire. Had

they been able to speak, they would certainly have given thanks for the

institution of a day of rest for beast as well as man.

We had one source of annoyance however. Two

stray dogs had joined our party uninvited, a brown one at Edmonton, and a

black at St. Ann's. They had been hooted, pelted and driven back, but

after going on a mile or two further we would see them slinking after us

again. Pemmican could not be spared, as we bought sufficient for our own

wants only, and to-day they looked particularly hungry. What was to be

done with them? Go back they would not. To take them to Kamloops was out

of the question. To let them die of starvation would be inhuman. There

seemed nothing for it but to shoot or drown them, and though each and all

of us promptly declined the part of executioner, their prospects looked so

gloomy that Frank, who had pleaded for them all along, resolved to try and

provide for them outside of our regular supplies. Getting permission to do

what he could, on the plea that it was both necessity and mercy, he rigged

a fishing line, and persuaded Brown and Valad to take a gun and try for

beaver or duck. While all three were away, the brown was caught in the act

of stealing pemmican. This aggravated their case, but, though all

condemned, none would shoot. The hunters too came back empty handed,

except with a pan-full of cranberries that Brown had picked, and that he

stewed in a few minutes into a delicious jam. The dogs puzzled us, so we

postponed further consideration of the problem till next day.

Instead of the usual three meals of pemmican,

bread and tea, we had only two to-day, and a simple lunch at one o'clock.

At six, dinner was served with all the delicacies we could muster,

Berry-pemmican, pork and cranberry jam made a feast so delicious that no

one thought of the dogs.

September 2nd.—Up at four and away at

half-past five, or twenty minutes after sunrise. Another bright and sunny

day, though the woods were so thick in some places that, at one o'clock

the dew was still on the grass.

Our first spell was six hours long. We crossed

the Lobstick a little above our camp, and followed up its course without

once seeing it again, to Chip Lake, from which it flows. The road ran

through a fertile undulating country at first, then through inferior land

which forest fires had desolated. There were few flowers or berries and no

large trees. The dogs roused a great many partridges, but no one felt

disposed to follow them into the bush. Brown shot a fine fat one from the

saddle with his revolver and divided it between the dogs, so that they had

a meal and therefore a respite for another day.

Our progress was so slow, averaging only two

miles an hour, that we were all dreadfully tired. The trail was not bad in

itself, with the exception of a few small morasses, some of black muck,

and others of a tenacious clay, but at every four or five yards a tree, or

two or three branches were lying across, as firmly set by having been

trodden on as if placed in position, and they prevented the horses from

getting into a trot. These obstacles were not recent windfalls. They had

evidently been there for years, and an expenditure of five or ten dollars

a mile would clear most of them away. But the H. B. Company could hardly

be expected to make a road for free-traders to Jasper House, and it is

everybody's business, not a hand is put to the work. Our dining place was

at a small creek that runs into Chip Lake, a lake half as big as St.

Ann's, that the thick woods prevented our seeing. The ground was

plentifully covered with creepers that yielded blueberries smaller and

more pungent than those in the Eastern Provinces.

A little after two P.M., we crossed the creek,

and wound up the opposite hill-side into a broken well-wooded country, the

hollows in which were furrowed with beaver dams. After an hour of this we

reached a hill-top, from which a great extent of thickly-wooded country

opened out, first level and then with an undulating upward slope to the

watershed of the McLeod. The horizon far beyond this slope in a due

westernly direction was bounded by dim mountains, that we hailed with a

shout as the long sought Rocky Mountains, but Beaupré checked the cheer by

calling back that they were only the "foot hills" between the McLeod and

the Athabasca. At any rate they were the outliers of the Rocky Mountains,

and in exactly a month from our saying goodbye to Governor Archibald at

Silver Heights we had our first glimpse of them.

The road now descended to lower ground, and

passed over the beds of old creeks destroyed by beavers. Had it not been

for half-decayed logs lying across the path, the horses could have trotted

the whole way. As it was, they made fully four miles an hour, in the

afternoon spell of three-and-a-quarter hours. Before five o'clock we came

to a beautiful, clear, cold stream and Valad advised camping, but the

Chief, learning that there was a suitable place with good water and feed

four miles farther on, gave the word to continue the march. This ground

like much that we had gone over in the morning, consisted either of old

willows and alders, dry marsh, or sandy and gravelly ridges covered with

scrub pine. It was part of the level region we had seen from the hill-top,

and had a decidedly poverty-stricken look. In an hour we had reached the

camping place and prepared our lodging for the night, well pleased with

the progress that had been made during the day. The spare horse, however,

which as usual had been left to himself to follow in his own way, was

missing. Terry, who had brought up the rear, had seen him lounging and

looking back when within a mile of the camp. Beaupré at once started in

pursuit bridle in hand, but returned at dusk without him. He had seen him

near the creek we had crossed at five o'clock, evidently on his way home

or in a state of bewilderment, not knowing where he was going. Beaupré had

tried to drive him into camp, but he plunged into the woods and refused to

be driven back; so Beaupré, afraid of losing the trail in the darkness,

returned. As the horse could not well be spared, Valad was asked to go

after him early next morning, try his luck and catch up to us before dark,

while we went on under the guidance of Beaupré for the day.

The evenings were getting long now and, after

our slow and tedious journeying, it was pleasant to sit in the open tent

before a great pine fire and talk about the work of the day, the prospects

of to-morrow, and hear some story of wild western life from the men. Brown

gave us the particulars of the horrible massacre of the Peigan Indians by

Colonel Baker, the kindly views of it taken by the Montana citizens, and

their memorial to Washington in his favour when he was threatened with

court-martial. Brown and Beaupré themselves judged the massacre from a

miner's stand point.

But none of their stories of lawless and cruel deeds roused in us such

indignation as what they told concerning villanies done recently in our

own North-west. Perhaps the worst had happened only three weeks before our

arrival at Edmonton, within one hundred yards of the Fort. A young Metis

of eighteen summers, son of a well known hunter called Kiskowassis (or

"day child," born in the day) had murdered his wife, to whom he had been

married only a few months and who was enceinte. Last year he had slashed a

woman with his knife in the wrist and made her a cripple for life. That

was a small affair. But, having gone to the plains and formed an intimacy

with another girl, he wanted to get rid of his wife. Luring her down to

the river side, so that suspicion might fall on a party of Blackfeet

camped on the other side, he stabbed but only wounded her, and she fled up

the hill, he chasing and striking at her. Some of the Blackfeet on the

opposite bank cried manoyo, manoyo, (murder), but there was no one near to

help the poor creature, and soon a surer blow stretched her dead. This was

too serious to be altogether passed over, so her brothers promptly called

on Kiskowassis about it. Charley—the murderer—was not at home, but

Kiskowassis acknowledged that he had gone too far, and proffered two

horses that he extolled highly, the one as "a hunter" and the other as "a

carter," in atonement. The elder brother went out and came back in a few

minutes, saying: "They're pretty good horses, I guess we'd better take

them." And thus the affair was amicably settled; and, at the same price,

as far as law on the Saskatchewan is concerned, Charley may go on and have

his six wives more easily than Henry the eighth. An uncle of Charley, on

the plains two months ago, shot a man who had offended him; and Beaupré

extolled the whole family as "very brave." Charley had tried to enlist

Beaupré last year in a promising enterprise of killing some Sursees who

owned good horses: but Beaupreé was not "brave" enough. There is a young

brother, aged fourteen, who Beaupré says is sure to beat even Charley: "he

is bound to steal a horse this very summer from the Black-feet."

We asked Brown why at any rate the miners did

not lynch Charley, since no one else acted. He said that there was such a

proposal, but it was decided that as they were strangers enjoying the

"protection" of the country, it would not be seemly for them to interfere.

September 3rd. — Awoke at four A.M., and found

the fire burning brightly and Valad away in pursuit of the missing horse.

Partly owing to his absence the start was an hour later than yesterday's.

Leaving his saddle and some bread and pemmican on a tree we moved on. The

trail was a continuation of the willow and alder marsh of last evening,

but instead of being dry it was swampy, and the travelling heavy. The

brown dog caught a musk-rat that made a meal for the two, and gave them

another day's respite.

For the first eight or ten miles the road was

almost wholly swamp, till a creek was crossed that runs into Chip or

Buffalo Lake, and from it by the Lobstick into the Pembina. The watershed

of the McLeod then rose in a long broken richly-clothed slope. In five

hours from camp, at an average rate of three miles an hour, Root River

that runs into the McLeod was reached. The trail, which at no time was

better than a bridle path, was so heavily encumbered in places with fallen

timber that no trace of it could be seen. A rough path had to be broken

round the obstacle, and sometimes Beaupré had difficulty in finding the

trail again. Indian pears and moose-berries—the largest we had seen—grew

along the hill-side, in such quantities that you could often fill your

hand by leaning from the saddle, as the horse brushed past the bushes. We

halted two hours and a half at Root River, and, as there was a birth-day

at home, slap-jacks, mixed with berry pemmican were made as a substitute

for plumpudding, and, at dinner, the Chief produced a pint bottle of

Noyeau, which had been stored for some great occasion, and Minnie's health

was drunk in three table-spoonfulls a piece. Just as dinner was over,

Valad made his appearance. He had had a hard day of it following the track

of the horse, but came up to him at our yesterday's dining place, moving

quietly home-wards. Three times he turned him, but the horse always got

away by dashing into the brush. Valad then went ahead and set a wooden

trap on the road, but the horse avoided it, and Valad gave up the chase.

On his way back—he found that the squirrels had eaten his breakfast.

Shouldering his saddle, he followed our trail, and rejoined us at two

P.M., having walked forty-one miles and eaten nothing. His moccasins had

been cut with the stumps and thorns; but, though footsore in consequence,

he made light of it and went to work with his usual promptness. Beaupré

had been looking for half an hour, but quite in vain, among the long grass

and shrubs, for a bit that had dropped off one of the bridles. "We're all

right now" was his judicious remark, when Valad appeared, "the old man

will smell it if he can't see it."

Our afternoon spell was heavy work; crossing a

branch of the Root River, we came on a barren swamp, burned over so

thoroughly that there was not a trace of water nor of the trail for two

miles; the once heavily-timbered slopes all round had been devastated. On

our right a forest of bare poles, looking in the distance like a white

cloud, clung to the hill-side. Dead logs, poles, branches, strewed the

ground so abundantly that the horses could pick their steps but slowly.

After the barren, came the last ascent, and so gradual was it that we did

not know when we were at the top, and then instead of a rapid descent to

the McLeod, stiff marsh succeeded that got stiffer every mile. The sun set

before we got through half of the marsh, but at one spot, a dry ridge

intervening with good water near, Valad advised camping. In answer to our

question, 'how far off is the McLeod still?' he pointed to the sky saying

'the sun will be over more than half of that again before we see it.' This

settled the question, though in a disappointing way, as it put an end to

the hope of getting to Jasper's this week. Three of the horses, too, wore

a little lame, and things did not look quite as bright as when we started

in the morning.

September 4th.—The three lame horses were looked at immediately after

breakfast. The cause of lameness in all three cases was, that sharp strong

stobs or splinters had run into or just above their unshod hoofs; we half

wondered that some of them had not pulled their hoofs off, in struggling

to extricate them from tough and sharp fibrous roots. The splinters were

easily extracted from two, and, the third horse, allowing no one near his

hind leg, was managed dexterously by Valad. Passing one end of his

shaganappi lasso twice round his neck, he made two turns of the other end

round his body, and gradually slipped those turns down over his hind legs,

and tightened them. Tightening the rope at his neck now, the horse

resisted, but his legs being tied, his own struggles with a little shove

threw him, and when thrown he lay quiet as a lamb.

It had rained during the night, and the

morning was cloudy and threatening. At 9 A.M., the rain came on again,

after we had been two hours on the road, if the expression is allowable

when there was no road. The rain made travelling across the muskeg still

more difficult and uncomfortable. In six hours and a quarter we fought

through ten miles, six or seven of them being simply over a continuous

muskeg covered with windfalls. The horses stumbled over roots and timber

to sink into thick layers of quaking moss, and sometimes through these to

the springs underneath. The greater part of the ground bore tall

beautifully shaped spruce and poplar, chiefly spruce, from one to three

feet in diameter.

After crossing a little creek, the trail improved somewhat till it led to

the ancient bank of the McLeod, at the foot of which yawned a deep pool

with a bottom of tenacious clay, that had to be struggled through somehow.

The horses sinking almost to their bellies, floundered in the mud at a

fearful rate, with such effects on our clothes as may be conceived;

fortunately by this time we were quite indifferent on the subject of

appearances. The river was only a hundred yards from this, but the trail

led for half a mile up through a wooded intervale to "the crossing." A

little creek seamed the intervale, and the first open spot was strewed

with as many chips as would furnish a carpenter's shop, beside several

logs, two of them stripped of their bark and others cut into junks for

transportation. We had disturbed a colony of beavers, in their work of

building a dam across the creek and of laying in their winter supplies.

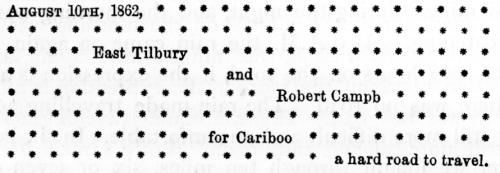

The sight of the McLeod was

a relief, for we had found the way to it "a hard road to travel," as the

Canadians who preceeded Milton and Cheadle evidently had also. The Chief

came upon their testimony chalked with red keil on a large spruce tree in

the swamp, five or six miles to the east of the river. Only the following

words and half-words could be made out:—

Poor fellows! some of them found the North

Thompson a harder road.

The McLeod heads inside of the first range of

the Rocky Mountains. Where we crossed, it is a beautiful stream about 110

yards wide, running north-easterly with a rapid current over a pebbly bed.

Its breadth is not much greater than the Pembina, but it has three times

the volume of water. At this season of the year, it can be forded at

almost any point where there is a little rapid, the water in such places,

not coming up to the horses' necks. Crossing, we came upon a few acres of

prairie, to the rich vetches on which the horses abandoned themselves as

eagerly as our party did to the richaud and tea that Terry hurried up.

Fortunately too, the rain ceased, though the sky did not clear, and Valad

made a big fire at which we dried ourselves partially. Brown advised that,

as this was a good place, some provisions should be cachèd for those of

the party who were to return from Jasper's; and Valad, selecting a site in

the green wood, he and Beaupré went off to it from the opposite direction,

with about twenty-five pounds of pemmican and flour tied up, first in

canvass and then in oil-skin, as the wolverine—most dreaded plunderer of

caches—dislikes the smell of oil. Selecting two suitable pine trees in the

thick wood, they "skinned" (barked) them to prevent animals from climbing;

then placing a pole between the two, some eighteen feet from the ground,

they hung a "St. Andrew's Cross" of two small sticks from the pole, and

suspended their bag from the end of one, that the least movement or even

puff of wind would set it swinging. Such a cache Valad guaranteed against

bird and beast of whatever kind. "And now,"' Beaupré summed up, "if no one

finds that, we will be in good luck ; but if somebody finds it, we will be

in bad luck; that's all."'

Our course from this point was to be up the

McLeod for nearly seventy miles of very bad road. As we had had enough of

that for one day, we listened eagerly to Beaupré saying that it was

possible to dodge the first eight miles by creeping along the shore of the

river, and crossing and recrossing wherever the banks came down too close

to permit travelling. Though Valad didn't know this way and Beaupré

himself had not tried the crossings, having on a former occasion made the

trip up the river in a canoe, and not by the shore, it was decided to try.

A very pleasant change on the forenoon's journey it proved to be, and

quite a success; for we arrived at the proposed camping ground, after four

crossings, before sunset. The river was low and the shore wide, consisting

of rough pebbly stretches or sand bars, covered, near the bank, with wild

onions, sand grasses, and creepers. Beaupré said that the sand would yield

gold at the rate of a cent a shovelful, but that would give only $2 or $3

per day. Where the banks came near the river in bold bluffs, they staged

sections chiefly of different kinds of clay and sandstone separated by

black slate. No coal beds appeared except a four-inch seam that looked

like coal, but may have been only a roof of shale to the coal beneath.

At the camp a roaring fire of pine logs was

soon kindled, and a line hung along one side for our wet clothes; but the

steady drizzling rain recommenced and continued all night. We warmed

ourselves at any rate, and 'turned in' as comfortably as the circumstances

permitted. September

5th.—It rained steadily through the night and was drizzling in the

morning. Though it hurts the horses' backs to saddle them when wet, there

was no alternative, and so after getting ready with great deliberation, in

hopes that it would clear up, we moved away at 7.30 A.M.

Our first "spell" was the hardest work of the

journey, so far, with the least to show for it. We made about five miles,

and it took as many hours to make the distance. The road followed the

upward course of the McLeod, crossing the necks of land formed by the

doublings of the river. These so-called, 'portages' were the worst part of

the road, though it was all so bad that it is invidious to make

comparisons. The country was either bog or barren—both bad,—for the whole

had recently been burned over, and every wind had blown down its share of

the burnt trees. There was no regular trail. Each successive party that

travelled this way, seemed to have tried to make a new one in vain efforts

to escape the difficulties. Valad went ahead, axe in hand, and between

natural selection and a judicious use of the axe, made a passage; but it

looked so tangled and beset, that the horses often thought they could do

better; off they would go, with a swing, among the bare poles, for about

two yards before their packs got interlaced with the tough spruce. Then

came the tug; if the trees would not give, the packs had to, and there was

a delay of half an hour to tie them on again. We often wondered that the

packs came off so seldom; but Brown understood his business; besides the

trees had been burnt, and some of them were uprooted or broken with

comparative ease. Of course the recent rains had not improved the going.

Beaupré said that it had not been worse last summer, after the spring

frosts had come out and the spring rains gone in. Take it all in all, the

road was hopelessly bad,—deserving all the hard things that had been said

of it,—and called for a large stock of the Mark Tapley spirit, especially

when, by wandering from the trail, the horses got mired in muskegs or

stuck between trees, or when the blackened, hard, tough spruce branches,

bent forward by a pack horse, swung back viciously in the face of the

unfortunate driver.

The road could only have been worse by the trees being larger; but then it

would have been simply impassable, for the windfalls would have barricaded

it completely. The prospect, too, was dismal and desolate looking enough

for Avernus or the richest coal fields: nothing but a forest, apparently

endless, of blackened poles on all sides. Only when an angle or bend of

the river came into view, was there any relief for the eye.

Towards midday, when every one's thoughts were

on pemmi-can, 'ho,' 'ho,' was heard ahead, and two Indians appeared

holding out hands to Valad. They had left Jasper's four days ago, and were

bound for Edmonton, trusting to their guns or the berries to supply them

with food on the way. The offer of a pemmican dinner turned them back with

us for quarter of a mile, to a little creek where the halt had to be

called, though there was but poor feed for the horses among the blackened

trees. The Indians had no dog, and were glad to take the black—as he would

be useful in treeing partridges—back to Mr. Adam's, to whom the Doctor

thought he belonged. They promised also to drive home the spare horse if

they could track him. We wrote a note by them to Mr. Adams, telling him

what commissions we had entrusted them with. These Indians had straighter

features and a manlier cast of countenance than the ordinary wood-Indians.

On inquiry, we learned that they were Iroquois from Smoking River, to the

north of Jasper's, where a small colony has been settled for fifty years

back. Their ancesters had been in the employment of the North-west Fur

Company, and on its amalgamation with the Hudson's Bay, had settled on

Smoking River, on account of the abundance of fur-bearing animals and of

large game such as buffalo, elk, brown and grizzly bears, then in that

quarter. After

dinner, the march was resumed at the mile per hour rate. More discouraging

was the fact that scarcely two-thirds of that modest speed was progress ;

for the trail twisted like a ship tacking, so that at times we were

actually progressing backwards. In struggling across creeks the difference

between the Lowland Scot and the Frenchman came out amusingly. Brown

continued imperturbable no matter how the horses went. Beaupré, the

mildest mannered man living when things went smoothly, could not stand the

sight of a horse floundering in the mud. Down into the gully he would rush

to lift him out by the tail. Of course he got spattered and perhaps kicked

for his pains. This made him worse, and he had to let out his excitement

on the horse. Gripping the tail with his left hand, as the brute struggled

up the opposite hill swaying him from side to side as if he had been tied

to it, he whipped with his right; sacré-ing furiously, till he reached the

top. Then feeling that he had done his part, he would let go and subside

again into his mildest manners.

Towards evening the road improved so that the

luxury of a smart walk was indulged in—with occasional breaks—for an hour

or two. When we camped, the tally for the day was twelve miles,

representing perhaps an air line of six or eight, for ten hours, hard

work. A bath in the McLeod, and a change of socks followed by supper, put

us all right, although the hope of seeing Jasper's before next Wednesday

had completely vanished.

September 6th.—It rained last night, but the

morning gave signs of a fair day. Renewed the march at 6.45 A.M.

Yesterday's experiences were also renewed, except that the road, as well

as the day, was better—enabling us to make two miles an hour,—and kept

closer to the river, revealing many a beautiful bend or long reach. The

timber was larger and less of it burnt. Poplar, cottonwood, and spruce,

chiefly the latter, predominated. The opposite bank had escaped fires.

Before noon, we got a glimpse of the mountains away to the south, and soon

after reached a lovely bit of open prairie covered with vetches,

honey-suckle, and rose-bushes out of flower. Here, the McLeod sweeps away

to the south and then back to the north, and the trail instead of

following its long circuit cuts across the loop. This 'portage' is twenty

miles long, and a muskeg in the middle—on one or the other side of which

we would have to camp to-night—is the worst on the road to Jasper's.

Halted for dinner at the bend of the river, having travelled nine or ten

miles, Frank promising us some fish, from a trouty looking stream hard by,

as a change from the everlasting pemmican. Not that any one was tired of

pemmican. All joined in its praises as the right food for a journey, and

wondered why the Government had never used it in war time. It must be

equal or superior to the famous Prussian sausage, judging of the latter,

as we needs must, without having lived on it for a month. As an army

'marches on its stomach condensed food is an important object for the

commissariat to consider, especially when as in the case of the British

Army, long expeditions are frequently necessary. Pemmican is good and

palatable uncooked and cooked, though most prefer it in the richaud form.

It has numerous other recommendations for campaign diet. It keeps sound

for twenty or thirty years, is wholesome and strengthening, portable, and

needs no medicine to correct a tri-daily use of it. Two pounds weight with

bread and tea, we found enough for the dinner of eight hungry men. A bag

weighing a hundred pounds is only the size of an ordinary pillow, two feet

long, one and a half wide, and six inches thick. Such a bag then would

supply three good meals to a hundred and thirty men. Could the same be

said of equal bulk of pork? But as Terry—an old soldier too—indignantly

remarked "the British Gauvirmint wont drame of pimmican till the

Prooshians find it out."

Frank came back to dinner

with one small trout, though Beaupré said that he and his mate last summer

had caught an hundred in two hours, some of them ten pounds in weight.

Perforce we dined on pemmican and liked it better than ever.

The sun now shone out, making the day warm and

pleasant, as all September usually is in America. At 2 P. M. got into line

again to cross the long portage. The course was westerly, by the banks of

the stream called the Medicine, at the mouth of which we had dined. A

great part of the road was comparatively free from fallen timber, so that

we enjoyed the novelty of a trot, and, except near two creeks that ran

into the Medicine,—free from the still worse obstruction of muskegs. An

hour before sunset, the Medicine itself had to be crossed, and on the

other side of it was the bad muskeg. Beaupré drew a long face when he saw

the river, for the recent rains had made it turbid and swollen to an

unusual height, and this augured ill for the state of the ground on the

other side. For the first mile, however, we got on well enough, as the

road took advantage of a ridge for two-thirds of that distance; but, then

came the dreaded spot. It looked no worse than the rest, but the danger

was unseen. Deep holes formed by springs abounded underneath the soft

thick moss, in which horses would sink to their necks. The task was to

find a line of sure ground, and by avoiding Scylla not to fall into

Charybdis. As Valad with Indian, and Brown with Scotch caution were trying

the ground all round, Beaupré leading his horse by the bridle dashed in

close to the swollen river, at a most unlikely spot, exclaiming "I'll

chance it any way." The words were only out of his lips when he fell into

a pool up to his middle; but, undismayed he scrambled out and keeping

close to beds of willows and alder, actually found a way so good that all

the rest followed him. Only one pack-horse sank so hopelessly deep, into a

hole, that he had to be unpacked and lifted out, Beaupré hoisting by the

tail with a mighty hoist—for the man had the strength of a giant. An hour

after sunset, we arrived at an ascent where it was possible to camp,

though the bare blackened half-burnt poles all round gave a cheerless

aspect to the scene. All were too tired to be critical; thankful besides

that the worst was over, and that to-morrow, according to Valad there

would be 'un beau chemin.'

To-day we had travelled twenty miles,

representing probably fourteen on the map. As more could not have been

done, no one grumbled, though all devoutly longed for a more modern rate

of speed. Crossing muskegs, it is impossible to hurry horses, and when

fallen timber cannot be jumped or scrambled over, a single tree on the

path may necessitate a detour of fifty yards to make five. How the heavily

laden pack-horses of the Hudson's Bay Company get along such a road, is

rather a puzzle?

September 7th.—We got away from camp at 6.45 A.M.; and in less than two

hours came again in view of the McLeod;—narrower and much more like the

child of the mountains than at the first crossing. Instead of sand bars as

there, ridges and masses of rounded stones and boulders are strewn along

its shores, or piled up with drifted trees and rubbish in the shallower

parts of its bed. The trail led up stream near the bank, descending

headlong to the river two or three times, and then ascending precipitous

bluffs that tested the horses' wind severely. From these summits, views of

a section of the Rocky Mountains, sixty or seventy miles away to the

south-west, rewarded our exertions, and were the only thing that justified

Valad's phrase of 'beau chemin.' The deep sides of the mountains and two

or three of the summits were white with snow, and under the rays of the

sun one part looked green and glacier-like. We should have crossed and

then recrossed the McLeod hereabouts to escape the worst part of the road,

but Valad, to his own intense mortification, missed the point where the

trail led oft to the ford. There was nothing left, therefore, but to keep

pegging away at the rate of a mile an hour, up and down hill, through

thick underbrush of willows and aspens that had sprung up round the burnt

spruce and cotton-wood, which still reared aloft their tall blackened

shafts. At I o'clock,

we dined beside the river on the usual breakfast and supper fare, having

travelled twelve or thirteen miles in six hours and a quarter. Muskegs and

windfalls delayed us most, the former being always near creeks, and worse

than the latter. The only hard ground was on the sandy or gravelly ridges

separating the intervening valleys, and on these, windfalls had

accumulated from year to year, so that the trail in many places was buried

out of sight. While at dinner, clouds gathered in the west and quickly

overspread the whole sky. This hurried our movements, but the rain was

on—with thunder and lightning— in ten minutes. After the first smart

shower, a lull followed which the men took advantage of to pack the

horses, drying their backs as well as possible before putting on the

saddles. A little

after 3 P.M., we were on the march and on rather a better road, though of

the same general character as in the morning. Heavy thunder showers broken

by gleams of sunlight dispelling the leaden clouds from time to time, gave

a sky of wonderful grandeur and colour. The river and the finely wooded

hilly country beyond, for hereabouts too the opposite banks had escaped

the ravages of fire—probably because there was no trail and no travelling

on that side, displayed themselves in magnificent panoramic views from

every bluff we climbed, while far to the west and south-west beyond the

hills, masses of clouds concealing the mountains but assuming the forms

and almost the solidity of the mountains, made an horizon worthy of the

whole sky and of the foreground. At sunset we descended for the last time

to the river, and skirting it for two miles or crossing to long islets

where the current divided itself, reached a beautiful prairie and camped

under the shade of a group of spruce and poplars. This was the point Valad

had aimed for, as a good place for the Sunday rest, chiefly because of the

feed; and here we were to take leave of the McLeod, and cross to the

Athabasca— 'No more by

thee our steps shall be

For ever and for ever,'

or at least until there is a better road, was

gladly chorussed, for we were all heartily sick of the McLeod. From its

watershed to this point was less than eighty miles, and to get over that

distance had occupied four and a half days of the hardest travelling. The

tally of the week was 120 miles, and every one was satisfied with it

because more could not have been done. And when, on the only occasion in

the week on which spirits were used, the whole party gathered round the

camp-fire after supper to have the Saturday night toasts of ' wives and

sweethearts' and 'the Dominion and the Railroad, 'immediately after ' the

Queen,' the universal feeling was of thankful content that we had got on

without casualties, and that to-morrow was Sunday. The men being without

waterproofs had not an inch of dry clothing on them, but they dried

themselves at the big fire as if it was the jolliest thing in the world to

be wet. Valad, under the influence of a glass of the mildest toddy,

relaxed from his Indian gravity and taciturnity, and smiled and talked

benignantly. 'When with gentlemen' he was pleased to inform us, 'he was

treated like a gentleman; but when with others he had a hard time of it'

Poor Valad! what a lonely joyless life he lived, yet he did his duty like

a man, and bore himself with the dignity of a man who lived close to and

learned the lessons of nature. Some will blame us for giving toddy to an

Indian, or for taking it ourselves, and perhaps more severely for not

suppressing all mention of the fact. Our only answer is that a little did

us good and we were thankful for the good, and that the one merit this

diary aspires to is to be a frank and truthful narrative. It would have

been mean to have left Valad out; and to show an Indian that it was

possible to be temperate in all things, possible to use a stimulant

without abusing it, seemed to us on the whole a better lesson to enforce

practically, than to have preached an abstinence that he would have

misunderstood.

September 8th.—Another Day of rest, with nothing to chronicle save our

ordinary Sunday routine. But no,—this is doing great injustice to the

Doctor who eclipsed all his former efforts, in the way of providing

medical comforts, by concocting a plum-pudding for dinner. The Doctor's

prescriptions smelled of the pharmacopoeia as little as possible. Was an

old woman that he met on the way complaining of 'a wakeness?' Send her a

pannikin of hot soup. Were Valad's legs inflamed by rubbing all day

against his coarse trowsers in the saddle? Make him a present of a pair of

soft flannel drawers. Was a good 'Father' at the mission in failing

health? Fatten him up with rich diet, even on fast days. And finally were

we all desirous of celebrating a birth-day, and did the thought make us a

little homesick, the only sickness that our own party ever suffered from?

Get up a plum-pudding for dinner.

But how? We had neither bag, suet, nor plums.

But we had berry pemmican, and pemmican in its own line is equal to

sha-ganappi. It contained buffalo fat that would do for suet, and berries

that would do for plums. Only genius could have united plum-pudding and

berry pemmican in one mental act. Terry contributed a bag, and, when the

contribution was inspected rather daintily, he explained that it was the

sugar bag, which might be used as there was very little sugar left for it

to hold. Pemmican, flour and water, baking soda, sugar and salt were

surely sufficient ingredients; as a last touch the Doctor searched the

medicine-chest, but in vain, for tincture of ginger to give a flavour, and

in default of that, suggested chlorodyne, but the Chief promptly negatived

the suggestion, on the ground that if we ate the pudding the chlorodyne

might be required a few hours after.

At 3 P.M. the bag was put in the pot, and

dinner was ordered to be at 5. At the appointed hour everything else was

ready the usual piece de resistance of pemmican, flanked for Sunday

garnishing, by two reindeer tongues. But as we gathered round, it was

announced that the pudding was a failure ; that it would not unite; that

buffalo fat was not equal in cohesive power to suet, and thar instead of a

pudding it would be only boiled pemmican. The Doctor might have been

knocked down with a feather; Frank was loud and savage in his lamentations

; but the Chief advised 'more boiling,' as an infallible specific in such

cases, and that dinner be proceeded with. The additional half hour acted

like a charm. With fear and trembling the Doctor went to the pot; anxious

heads bent down with his; tenderly was the bag lifted out and slit; and a

joyous shout conveyed the intelligence that it was a success, that at any

rate it had the shape of a pudding. Brown, who had been scoffing, was

silenced; and the Doctor conquered him completely by helping him to a

double portion. How good that pudding was! A teaspoonful of brandy on a

sprinkling of sugar made sauce; and there was not one of the party who did

not hold out his plate for "more," though, as the Doctor belonged to the

orthodox school of medicine, the first helping had been no homoeopathic

dose. To have been perfect the pudding should have had more boiling; but

no one dared hint a fault, for was not the dish empty? We at once named

the place Plum-Pudding Camp, and Brown was engaged on the spot to make a

better if he could at the Yellow Head Pass Camp.

In all respects save weather the day was as

pleasant as our former Sundays; but gusts of wind blew the smoke of the

fire into the tent, and the grass was too thoroughly soaked with rain for

pleasant walking. The sun struggled to come out but scarcely succeeded,

and towards evening a cold rain, that would be snow on the mountains, set

in. Valad had pitched a separate camp for himself under a grove of pines,

that sheltered him beautifully from the wind and rain. So cozy was it that

during the day one after another resorted thither, for a pipe or a quiet

read, when eyes could no longer endure the big tent's smoke.

The usual morning and evening services were

attended by all. Without them the day would have been a rest, but