|

WE had spent two Sabbaths and

seventeen travelling days between Forts Canton and Pitt —days and nights of

extreme hardship. This was a bridal tour by no means lacking in the elements

of romance. Here we were now in a Hudson's Bay fort and among friends, the

gentleman in charge, Mr. McKay, and his two assistants, Philip Tait and John

Sinclair, all old friends of mine, giving us a right hearty welcome.

Moreover, they despatched two dog- trains to bring in our stuff from the

cart, and then helped me rearrange my travelling equipment. I decided to

leave my carts and waggon and take take in their place two horse toboggans

or flat-sleds. On the front of one of these we made a carry-all for Mrs.

McDougall. My friends also supplied me with a pair of snow-shoes, a most

welcome gift; and in addition Mr. Tait lent me two fresh horses, as two of

mine were nearly used up. The only difficulty was to find a man to accompany

us to Victoria, for Neche could not go with us farther than this point. He

had done his duty splendidly, and after settling with him we reluctantly

bade him good-bye.

In the meantime Sunday came

on, and I had the opportunity of holding two services with the people of the

fort and some Indians in camp near by. On Sunday who should come in but Jack

Norris and young Sandy, and here was our chance. Sandy wanted to go on, and

Jack was willing that I should have him with me. Jack reported a "terrible

time"; he had left. his party some sixty or seventy miles back, and had come

on to obtain flat-sleds, having decided to abandon his carts until spring.

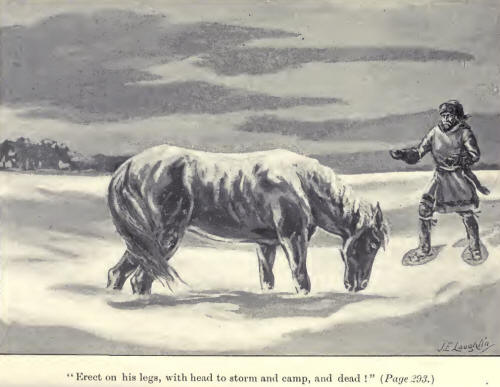

He told us of a most pathetic incident that had happened on the way. One of

their horses had played out, and, as I had done with Little Bob, they had

turned him loose to follow. The faithful animal had done this up to the

measure of his ability, but when he failed to come into the camp one night

they went back in the morning to look for him, and found him actually

standing with head to camp, frozen dead. I have seen and known of many a

horse, worn out with hardship and hunger, lying down to die, but here was a

case unique so far as I know—the poor beast erect on his legs, with head to

storm and camp, and dead!

Such was Archie's condition

that I had to leave him at the fort. One of the Hudson's Bay employees,

knowing him by repute, offered me a good price for him, and I let him go;

but Little Bob I could not leave, and I was fortunate in securing a keg of

wheat from Mr. McKay to keep him alive. My old Brown and new Fort Pitt Brown

were still to the front, fresh and strong, and with the two colts lent Inc

by Mr. Tait, and with flat-sleds and snow-shoes and Sandy, I was quite

hopeful as to the rest of the journey.

Bidding the hospitable

friends at Fort Pitt a grateful adieu, we started for Victoria, our next

objective point. Our line of march now was: Myself ahead on snow-shoes; Fort

Pitt Brown following, pulling a long toboggan with Mrs. McDougall carefully

wrapped in the coffin-like carry-all and a couple of trunks strapped on

behind her; then Old Brown in another sleigh with our travelling kit and

everything else lashed on to it, and Sandy and the two spare horses

following, with Little Bob bringing up the rear. Thus we began our trackless

journey through the deepening snow and strengthening winter. Of necessity

our progress was slow. I went straight from point to point, making as few

curves as possible. Sometimes after forging ahead a bit I retraced my steps

and met Brown, and then doubled back, thus giving him the benefit for miles

every day of my three tracks. Often as in the vigor of health and strength I

took a run on the snow-shoes I heartily wished that my party could keep up

with me for a few days and we would soon cover a long distance. But this was

impossible at the time; there was nothing for it but heavy and continuous

plodding. And Bob, brave fellow that he was, proved himself clear grit.

Sometimes it would be nine o'clock when he would herald his approach with a

neigh, and I would run out and give him a pat and a welcome, and feed him

some of the wheat. Then at our noon spell, if he had not come up, I would

hollow a small basin in the snow and put a few handfuls of grain in the

track for him. Thus we journeyed on through storm and drift and bleak cold.

All the while I could not resist the feeling of shame at my act in bringing

that brave little woman from the east on such a journey; but never by hint

or act did my good wife indicate that she regretted the sacrifice she had

made.

On steadily we forged our way

by Frog Lake and Moose Creek and the Dog Rump and Egg Lake. Poor horses, how

their legs bled as the snow crusted. New Brown led the way all the time.

Faithfully following behind my lead on snow-shoes, he climbed the drifts,

broke them down and pulled his load, failing not either in flesh or spirit.

A most wonderful horse was New Brown. The night before we reached Victoria

we camped with a French half-breed family by the name of McGillis. This was

a pleasant break in the journey, for their hospitality was genuine and

natural. The women were all greatly interested in Mrs. McDougall; they

thought she was a plucky girl to undertake such a journey, and made her

blush by telling her she must have loved her husband very much to leave her

people and come so far to this big, strange country. However, they said,

"John was a good fellow." At any rate their shanty was warm, and it was no

small relief not to have to make camp, nor to perform the pivotal act of

turning around to the fire or from it every few minutes. Really it was a

pleasant change, and we made up our beds on the floor and slept in

peace—that is, it would have been peace if I could have forgotten my horses,

bleeding and sore with the almost constant crust we had come through for

days, and which had been especially bad to-day. Poor Bob was the worst. Thus

far he had kept up, though sometimes coming in late, and always had

announced his arrival with a cheerful neigh which said, "Still alive and

hopeful!" But we had yet a long day under these conditions before we would

reach Victoria, and I felt anxious as to how Bob would stand it. From my

horses I fell to thinking about these people under whose humble roof we were

camped. These were not settlers; no, no, only wintering. The head of the

colony, Cuthbert McGillis, was a genuine type of the mingling of the two

races, the careless, happy, plutocratic habitant with the nomadic Indian,

the truly aboriginal man; a mixture of semi-civilization and absolute

barbarism. A gigantic, curly-headed, splendid specimen of physical humanity

he was, ever ready to fight anybody, but the friend of everybody. A

life-long plainsman, a genuine buffalo eater, he is now away with the men of

his party looking for meat one hundred and fifty miles west of here. We have

been friends ever since we first met. His big, hearty ' John, my friend,"

rings in my ear as I write, and I often wonder that such men should ever

have come to take the stand some of them did in 1870 and later. Certainly

the trouble did not originate with themselves; of this my years of kindly

intercourse and interdependence make me very sure. These are not the

material out of which disloyalty comes as indigenous to the soil.

Early the next morning, with

a hearty handshake all around from these native women and children, and a

sincere "bon voyage," we are off to again take up our slow and solemn

procession over the Snake Hills and through the Vermilion valley and across

the White Mud Heights. The day is short, and it is dark ere we cross the

White Mud River. My wife is beginning to think this road interminable and

the North- West without end. In the latter thought she is about right so far

as things terrestrial go, and the generations to come will still be turning

up fresh resources and endless wealth in this wonderful land. On through the

sombre, pine- shadowed trail leading by the Smoking Creek, and we strike the

beautiful valley north of Victoria. Little Bob is on his last strength.

Presently he comes to a stop, utterly fagged, and I gently coax and push him

up the hill a little farther. But I see that it is no use; we must go on and

then come back to his relief, and about 9 p.m. we bring up at my brother's

house, where we are welcomed most heartily. Here I found my eldest little

daughter, Flora, but was pained to find my good sister-in-law in terrible

distress with an ulcerated breast. Within the last few weeks their

first-born, a fine little girl, had come upon the scene, and now the young

mother was undergoing one of those great sacrifices which ever and anon come

to the motherhood of our humanity. David had been away on the plains hunting

buffalo and grisly bears, and was caught in the same early storm we had been

struggling through; but he was with a strong party and much nearer home, and

he had but recently returned to find himself a father. A fonder or more

attentive one I had never seen. The little tot had but to move or whimper

and David was all alive, be it day or night. To him the responsibility of

parenthood had come in full force, and I was proud to witness such affection

and true manhood in my brother. After asking about us, the next question was

as to our horses, and when I mentioned Bob standing on the trail about two

miles back, David at once exclaimed, "We must go for him right off." But I

said, "No, we will take him a bundle of hay and a little barley, and let him

eat and gather strength, and he will come in himself." Sandy immediately

volunteered to take the hay and barley back to Bob, and though wearied with

the long day's tramp this willing fellow got out one of David's horses,

hitched him to a sleigh, threw on a bundle of hay and some barley, and drove

back to find Bob just where we had left him. Leaving him the feed he

returned, and we anxiously awaited developments, meanwhile seeking to do

what we could for our sick sister, who was delighted to have another sister

come into her home for a time. While at breakfast the next morning we heard

a loud neigh, as much as to say, "I am upon the scene once more," and there

was Little Bob, head up and proud at having survived all the hardships and

loss of blood and the cold and starvation he had come through. It is

needless to say he was taken into a warm stable and looked after with all

care; our whole family had an interest in that faithful little horse.

I concluded to leave my wife

and horses at Victoria, take a train of dogs, and go on to Edmonton and

Pigeon Lake. Mrs. McDougall required the rest, and she was needed in the

home of my brother. Certainly, too, my horses needed a chance to mend and

heal, for we still had another hundred and fifty miles ahead of us ere we

should reach home. That afternoon I was off on the jump with a train of

borrowed dogs, and camping alone for part of the night reached Edmonton

early the next day. Father was well pleased but not wholly surprised to see

me. "I knew you would come," were his words of greeting; others had given me

up, but he had not. I spent a delightful evening and night between the

Mission and the fort, where my brother-in-law, Richard Hardisty, was in

charge, and went on to Pigeon Lake next day, where I found Donald with

everything in order. I was welcomed most heartily by all the Indians and

half-breeds in the vicinity, and held a number of services. Arranging with

Donald for some changes in the little home, I returned to Edmonton, whence I

was accompanied back to Victoria by my sister Libby. I was grieved to find

my sister-in-law worse, and suggested that we at once send for father. This

was agreed to, and a smart man and a train of first-class dogs were

despatched to Edmonton for him. In an incredibly short time father was on

the scene, and, I am glad to say, was instrumental in relieving and helping

our patient.

After a day or so in company

with father, we continued our journey westward, leaving Little Bob to

David's skilled care, and with Fort Pitt Brown still fresh and fat and

pulling his new mistress, we made good time to Edmonton. The weather

continued cold and the snow was deepening all the while. There had been no

such winter on the Saskatchewan in all my experience. At Edmonton we met

some new arrivals, notably Donald Ross, who had come in by way of the Peace

River, and being quite a singer and amateur elocutionist, was a great help

in the social life of the place. We spent Christmas with the Edmonton folk,

and thoroughly enjoyed the rest and fun of the holiday season in this

far-away upland centre. Here was a small world in itself, isolated and

alone. No mail, no telegraphs, only a few Hudson's Bay Company traders and

missionaries and adventurers, and yet the Sabbath services and week-night

entertainments of the winter of 1872-3 would do credit to many a larger

place. Indeed, had these hardy pioneers not strained to keep up in those

things which appeal to the mental and spiritual, there would have been a

terrible lapsing into barbarism. Lectures and literary entertainments and

concerts, as also a growing interest in church work, kept these men and

women shoulder to shoulder with the best in any country. In all this father

took the lead, and was much respected and reverenced by both the white and

the red men.

Between Christmas and the New

Year we pushed on to our own home, taking with us my two older girls, Flora

and Ruth. Again we were facing the deep snow and extreme cold, and still

Fort Pitt Brown was to the front, as strong and faithful as ever. Reaching

Pigeon Lake without further adventure, we were at the end of our long

journey. Two months and a half had elapsed since we left Portage la Prairie,

and considerably over three months from our leaving eastern Canada. Long

weary miles we had journeyed, with cold camps, deep snows, intense frosts

and blinding snow-storms as accompaniments; but here we were at last, well

and strong and thankful. And our people at the lake were also thankful.

Donald and all the rest of the natives welcomed our coming, and soon the

chimneys of our two-roomed shanty were belching forth sparks and smoke, and

by New Year's eve we were comfortably domiciled. My wife had undergone great

hardships. Perhaps there never had been just such another bridal trip as

this we had come safely through. To start thoroughly prepared for a winter

trip such as ours would be hard enough in all truth, but to be caught as we

were, almost wholly unprepared, while yet six hundred miles intervened

between us and our destination, added tenfold to the dangers and

difficulties. Truly my little wife, who bravely endured all this without a

murmur, deserves to be ranked among the heroines of frontier life.

And now the time has come to

close my present narrative. In these pages the reader has accompanied me in

my wanderings from the autumn of 1868 down to the eve of New Year's day,

1873. We have travelled together over new and strange fields, have witnessed

many scenes in the wild life that in those days prevailed throughout our

great western domain, and now for the time being I will say farewell,

trusting ere long to resume the story of my early experiences on the mission

fields of the Canadian West.

Yours faithfully,

JOHN MCDOUGALL. |