|

OUR stay at Alderville was

not a long one. Within a year my father was commissioned by the Church to

open a mission somewhere in the north country, among the needy tribes who

frequented the shores of lakes Huron and Superior.

After prospecting, he

determined to locate near the confluence of the "Soo" and Garden rivers.

Behold us, then, moving out

by wagon, on to Cobourg, and taking steamboat from there to Toronto; from

thence staging across to Holland Landing. Then going aboard the steamer

Beaver, we landed one evening at Orillia, took stage at once, and pounded

across many corduroy bridges to Coldwater, where, in the early morning, we

went aboard the little side-wheeler Gore, and then out to Owen Sound, where

my brother David joined us, and we sailed across Georgian Bay, up through

the islands into the majestic river which connects these great lakes, and

landed at the Indian village of Garden River.

I am now in my ninth year,

and, as father says, quite a help.

We rented a small one-roomed

house from an Indian, and into this we moved from the steamboat. Whiskey was

king here. Nearly all the Indians were drunk the first night of our arrival.

Such noise and din! We children were frightened, and very glad when morning

dawned.

Things became more quiet, and

now we went to work to build a mission house, a church, and a school-house.

Father was everywhere—in the

bush chopping logs, among the Indians preaching the Gospel, and fighting the

whiskey traffic. I drove the oxen and hauled the timber to its place. I

interpreted for father in the home and by the wayside. My brother and myself

fished, picked berries, did anything to supplement our scanty fare, for

father's salary was only $320, and prices were very high. In our wanderings

after berries I had to be responsible for my brother. The Indian boys would

go with us. Every little while I would shout, "David, come on!" They would

take it up, "Dape-tic-o-mon!" This was how the sounds came to their ears.

This they would shout; and this they named my brother, and the name still

sticks to him in that country.

My Indian name was "Pa-ke-noh-ka"

("the Winner"). I earned this by leaving all boys of my age in foot-races.

After some months of hard work we got the home up, and moved into it. Then

the school-house was erected.

A wonderful change was going

on in the meantime. The people became sober. To see any drunk became the

exception. A strong temperance feeling took hold of the Indians. Many of

them were converted. Though but a boy, I could not help but see and note all

the changes. What meetings I attended with father in the houses, and camps,

and sugar-bushes of the people!

Our means of transport were,

in summer, by boat and canoe, and in winter, by sleigh and snow-shoes.

Many a long trip I had with father in sail or Mackinaw boat, away up into

Lake Superior, then down to the Bruce Mines, calling en route and preaching

to a few Indians who lived at Punkin Point. We sailed where the wind would

let us. Then father would pull and I would steer, on into the night, across

long stretches and along what seemed to me interminable shores.

How sleepy I used to be 1 How

often I wondered if father over became tired. He would preach, and pray, and

sing, and then pull, as if he was fresh all the time.

Then, in winter, with our

little white pony and jumper, which my father had made, we would take the

same trips. Sometimes the ice would be very dangerous, and father would take

the reins out of the rings and give them to me straight from the horse's

mouth, saying, "If she breaks, through, John, keep her head above water if

you can." And then father would take the axe he carried and run ahead,

trying the ice as he ran. And thus we would reach those early settlements

and Indian camps, where father was always welcome.

In summer, in coming to or

from Lake Superior, we always portaged at the "Soo," on the American side.

Coming down father would put

me ashore at the head of the rapids, and he would run them.

While we were in that country

the Americans built their canal.

Father was chaplain for the

Canal Company for a time.

I saw a big "side-wheeler"

being portaged across for service on Lake Superior. It took months to do

this. By and by I saw great vessels locking through the canal.

Our Indians got out timber

for the canal. Some of my first earnings I made in taking out timber to

floor the canal.

Father became well acquainted

with the Canal Company. Once a number of the directors with the

superintendent came to Garden River in one of their tugs, and prevailed on

father to join the party. He took me along.

Away we flew down the river,

and when near the mouth on the American side, we met a yawl pulling up

stream. Who should this be but the Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, Sir

George Simpson. He stood up in his boat and hailed us, and told us that a

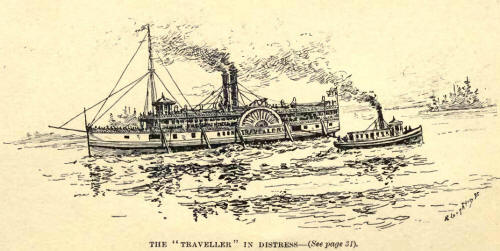

big steamer named the Traveller, was aground over between the islands. She

had started to cross over to the Bruce Mines and come up the other channel.

He said you will confer a great favor if you go over and give her all the

help you can. She is loaded with passengers, and they are running great

risks should a storm come on before she is got off.

Accordingly we went to the rescue, and as a messenger from Providence were

we welcomed by the great ship. We launched a nice little log canoe that

father had taken along, and he got into it and felt and sounded a way for

us, for our small vessel drew almost as much water as the big one; but

father piloted our tug close to the great vessel. Soon we had a big hawser

hitched to the stern of the steamer.

I well remember the time, for I was in the cabin at supper when our tug,

with all steam on and with a jump, gathered in all the slack.

What a jerk! and then snap

went the big rope as though it had been so much thread, and away I went to

the other end of the small cabin. Crockery, cutlery, and boy brought up in a

promiscuous heap. Then we broke another big rope in vain, and it was

concluded that the most of our passengers should go on to the steamer, and

father should pilot the tug over to the Canadian side, where there was a big

scow or lighter, and bring the latter, and thus lighten the ship.

Darkness was now on the

scene, and the big ship, all lit up, presented a weird sight stuck on a bar

and in great danger if the wind should come off the lake, which fortunately

it did not.

Father started with the tug

at first peep of day, and about two o'clock in the afternoon came back to us

with the big barge in tow. This was placed alongside the steamer, and all

hands went to work to lighten her.

In the meantime two anchors

were got out astern. One of these was to be pulled upon by the windlass, and

the other by the passengers—for there were some three hundred on board.

Everybody worked with a will, and soon all was ready. Steam up on the

steamer, our tug hitched to her ready to pull, the passengers ranged along

the rope from one anchor away astern, the other rope from another anchor on

the windlass. Some of the crew rolled the ballast barrels to and fro, to

cause the ship to roll, if possible. When all was ready the whistle blew,

and all steam was put on both big and little ships, the passengers pulled as

for life, the capstan turned, the big vessel seemed to quiver arid

straighten, and after moments of great suspense began to move backwards off

the shoal. What shouting, what cheering, once more the huge ship was afloat!

As it was now late we started

for the Bruce Mines, our tug taking the lead and the steamer following.

About dark we reached the docks at the Bruce Mines, where we lay all night.

Our watchman slept at his

post, and allowed the big ship to get away ahead of us in the morning, but

when we did start, we flew. Our superintendent was determined to overhaul

her before she could reach the "Soo," and so he did, overtaking and passing

her in Big Lake George, while she was scratching her way over the shoal,

which at that time was not dredged out as now. Then, when the last boat went

east in the fall, all that western and upper country was left without

communication until spring opened again.

Under these circumstances you can imagine with what eagerness we looked for

the first boat of the season.

I well remember I was hauling

timber to the river bank with a yoke of oxen, some little ways down from the

Mission, when the boat came along. All I could do was to wave my gad and

shout her welcome. Looking up the river, I saw my brother Dave, with

father's double-barrelled gun, standing to salute the first steamer. Dave

either did not know or had forgotten that father had put in an unusual big

charge for long shooting, and when the boat came opposite to him he fired

the first barrel, and the gun knocked him over. The passengers and crew of

the steamer cheered him, and, nothing daunted, he got up, fired the second

barrel, and again was knocked over. This was great fun for the steamboat

people, and they cheered David, and threw him some apples and oranges, which

he, dropping the gun, and running to the canoe, was soon out in the river

gathering.

Some of this time mother was

very sick, and David and I had all the work to do about the house—wash,

scrub, bake, cook, inside and outside. We found plenty to do. When not

wanted at home we went fishing and hunting. Then I found employment in

teaming.

I worked one winter for an

Indian, hauling saw-logs out of the woods to the river bank. He gave me

fifty cents per day and my board. In the summer. I sometimes sold cordwood

on commission for Mr. Church, the trader, and when he put up a saw-mill, a

couple of miles down the river, I several times got out a lot of saw-logs

and rafted them down to the mill.

I also hauled cordwood on to

the dock with our pony and a sleigh, for there were no carts or wagons in

the country at that time, nor yet had we the means to buy them.

I think I made a good

investment with my first earnings, a part of which I expended in the

purchase of a shawl for my mother, and a part I saved for the next

missionary meeting as my subscription thereto.

Father was stationed for six

years at Garden River.

During this time he sent me

down to Owen Sound for one winter, in order that I might attend the public

school, there being none nearer to which I might have access. I must have

been eleven or twelve years of age at this time. My parents put rue on the

steamer—the Kalloola. I was placed in care of the mate, and away we went for

the past. All went well until we reached Killarney; then we struck out into

the wide stretch of Georgian Bay. It must have been the middle of the

afternoon that we took our course out into the "Big Lake." In the evening

the wind freshened, the sky became dark, the scuds thickened, and there was

every indication of a storm. The captain shook his head; old Bob, the mate,

looked solemn; everything was put ship-shape.

Down came the storm, and for

some hours it seemed doubtful whether we should weather it. Some of the

bulwarks of our side-wheeler were smashed in. Our vessel labored heavily.

Passengers were alarmed; some of them who had been gambling and cursing and

swearing during the previous fine portion of the voyage, were the. most

excited and alarmed of the lot. The captain had to severely reprimand them

at last.

Again I took mental note that

loudness and profanity are not evidences of pluck or manliness.

Old Bob was about to lock me

in my stateroom, but I pleaded to be allowed to remain with him on deck.

Signals of distress were made. The captain thought we were in the vicinity

of an island, and if we could be heard, some fishermen might light a

beacon-fire, and thus we might be saved by getting under the lee of the

island.

The danger was imminent.

Anxiety and sustained suspense were written on every face, when suddenly

through the black night and raging storm there flashed in view a glimmer of

light. Presently this assumed shape, and the captain was right, and we were

near an island; and in a little while, by dint of strong effort, we were in

the lee of the same and safe for the while. Then I went to sleep, and when I

awoke we were far on our course, and in due time reached Owen Sound. I went

to my uncle's, about two miles in the country, but still it was hard to

distinguish very much between town and country.

From my uncle's kind but

humble home, I wended my way every school-day to the old log school-house in

Owen Sound. The teacher believed in "pounding it in," for, like now,

"Children's heads were hollow." I saw a great deal of flogging, but somehow

or another, missed being flogged at that school. Through the rain and mud,

through the snow and slush, through the winter's cold, I plodded back and

forth morning and evening from school to the little log-house under the

limestone cliff.

This last autumn, in company

with my cousin, Captain George MacDougall (who was born in this log-house),

we drove out to look at the spot once more. The farm, hill, and cliffs were

there, but the house was gone. Here we had sheltered and played and grown,

and felt it was home— now it was gone. A strange home was built near the

spot, stranger people lived in it, and with feelings of melancholy we turned

away.

Twice during that winter I

had intermission from school. Another uncle came along and took me down to

Meaford, where my grandparents lived, and this gave me a delightful visit

and a holiday as well.

Another time I was chopping

and splitting wood in the morning, before starting for school, when the axe

slipped, and I almost cut my foot in two. Alas! I had my new boots on—long

boots at that. No one knows how much sacrifice my father and mother made to

provide me with those boots. I went and got my measure taken. Every other

day or so I went to see if the village shoemaker had finished them. At last,

after weary waiting, they were finished. How proudly I carried them home.

With what dignity I walked to school with them on! Very few boys in those

days had "long boots," and now alas! alas! I had cut one of them almost in

two. That was the thought that was uppermost in my mind, while my aunt was

dressing my foot and saying "Poor Johnnie," and pitying me with her big

heart; and I was, so far as my foot was concerned, rather glad, because it

bespoke another holiday from school. But my boot—could it ever be mended?

would it ever look as it had? Oh, this worried me a lot.

Early next summer I went back

to Garden River, and was delighted to be home again. Then father found a

place for me in the store of Mr. Edward Jeffrey, at Penetanguishene, and to

which place I went on the same old steamer. We happened to reach there late

one evening, when the whole town was in a blaze of burning tallow. Every

window had a candle in it, and we on the boat, as we steamed up the bay,

could not help but wonder what had happened, but presently as we neared the

wharf someone shouted across to us, "Sebastapol is taken; Sebastapol is

taken!"

Here was a "national " spirit

in earnest. Away in the heart of Europe British soldiers were in conflict;

they and their allies won a victory, and out here in the heart of this

continent, a hamlet on the shore of this distant bay is aflame with joy.

Why, I walked from the wharf to my future home amid a blaze of light. Every

seven-by-nine had a tallow-dip behind it.

Here, for about nine months,

I worked in the store and on the farm. The greater part of our customers

were "French," and I soon picked up the vernacular, and became quite at home

in serving them.

One day when I was in the

store alone, a drunken Indian came in and wanted inc to give him something;

in fact, demanded it. I refused, and he drew his long knife and started

around the counter after me. When he came near I vaulted over the counter,

and for some time we kept this up, I hoping someone would come in, and

failing that, I wanted time to reach the door, which I finally secured, and

throwing it open, called for help, when the crazy fellow took to his heels.

I would have thankfully informed on the man who gave him the liquor, but did

not like to push the poor Indian.

Here I was given one suit of

clothes and my board for my work, which always was so much; besides I

learned a lot which has been useful to me all through life.

Summer came, and with it my

father, who took me home with him. This time we drove to Barrie, and then

took the train to Collingwood.

This was my first ride on a

railroad; my thought was, how wonderfully the world is progressing. |