|

During the past few

decades the Dominion Government recognizing that sooner or later Canada,

as the pioneer found it, was certain to become nought but a memory,

decided to set aside huge stretches of primeval country as reservations

or parks, where the indigenous game might be able to roam hither and

thither unmolested, and where the hand of improving man would not bo

allowed to pursue its bent. The policy, though apparently fatuous at the

time when the West-was still wild and woebegone, to day is appreciated.

Canadians of two or three centuries hence, as well as the people of

other countries, will be enabled to catch a glimpse of what it was in

the distant past, by wandering through these domains.

The Government has not

been at all niggardly in its action. Not acres, but hundreds of square

miles, have been railed off for once and for all against development.

When tho forest has been cleared, and what are now dense tangled masses

of timber, become seas of brown earth, stretches of succulent

vegetables, or areas of waving com, these primeval islets will stand out

as oases of the hoary past. The most important of these reservations are

Algonquin Park in Ontario, of about 2,100 square miles, Jasper Park on

the eastern slopes of the Rockies, stretching over 5,000 square miles;

and Banff Park, in the province of Alberta, of 5,732 square miles area.

A more comprehensive idea of the size of these stretches of Wild Canada

may be gathered from the fact that Jasper Park is as large as Belgium,

and that it is threaded for nearly fifty miles by the Grand Trunk

Pacific Railway, while Banff Park and Algonquin Park are traversed by

the Canadian Pacific and Grand Trunk Railways respectively for mde after

mile. Even to day, although primeval Canada comprises many hundreds of

thousands of square miles, the parks are becoming more and more favoured

by the public, who have not the desire, or inclination, to wander too

far from the beaten track to see Canada as it was presented to the

daring pioneers in the earliest days of settlement.

Naturally these

reservations have to be patrolled and guarded against those who are

always ready to prey upon preserves, because the game therein is always

more plentiful and easily obtainable than in the wilds. The denizens of

the forest appear instinctively to know that within these stretches of

upland, valley, and mountain they are protected from their foes. The

poacher, whether two or four-footed, always regards such areas as happy

hunting-grounds, and to guard against such depredations, game-wardens

are appointed, whose one object in life is the guardianship of the park,

and all that it contains in the way of fur, feather, and fish life.

When the stranger

enters these precincts, his firearms are sealed, and on no account

whatever is he permitted to break the official embargo upon his weapons

within the confines of the park. Fish, likewise, are protected, every

disciple of Isaac Walton practising his art in the streams within the

boundaries of the reservation having the extent of his catch rigorously

limited by law.

The life of the

game-warden is probably one of the loneliest that has yet come into

vogue as a livelihood. Take Jasper Park for instance. Although it rolls

over 5,000 square miles of rugged, thickly wooded country, two men are

responsible for the safety and well-being of all the life. The idea of

two men being able to patrol and watch over such a large tract appears

absurd, but at the time I traversed the park, the trails through the

area wore very limited, and could be watched fairly easily. Our party

had scarcely entered when the protective official strode up, apparently

appearing from nowhere, and, within a few seconds, our firearms were

duly sealed in accordance with the law Having performed his duty the

warden, cheered at the sight of a few strange faces, stretched himself

on the sward before the camp fire, and regaled us with stories galore

concerning his life and adventures. Although dwelling in solitary state,

he was the jolliest fellow alive, and certainly the responsibilities of

his work and his fight for existence caused him no anxiety. When we

resumed our journey, we had not gone fifteen miles when we ran upon his

colleague, and had to display our weapons to convince him that the seals

were intact still. Had he found them otherwise a fine of £10 and the

confiscation of our firearms would have been the penalty.

But the loneliness of

the game-warden’s life was brought homo to us with more poignant

vividness as we were dropping down the 350 miles of the Upper Fraser

River. We were drifting along with two Indian dug-outs fastened

together, a la catamaran, when suddenly a blue Peterborough shot cut

into midstream from beneath the trees overhanging the bank so as to

intercept us. It was tbe game-warden patrolling 350 miles of waterway,

flowing through the wildest stretch of New British Columbia. We were in

the heart of the moose country, where these animals roam in large

numbers, magnificent specimens of which we had seen within a

stone’s-throw of our craft. Fortunately, we had not drawn upon them for

meat, otherwise this official would have caught us with the goods, and

thon there would have been something doing.

As we swung towards him

the arched back which had been crouching over the paddle bent itself

straight, and a pair of vigilant eyes searched our canoes through and

through. As we swung by him we gave a cheery “Hallo!” to which there was

a monosyllabic response, scarcely more than a guttural, and we were

permitted to go on our way. The occupant of the Peterborough bent his

arms to the paddle once more, and, driving towards the bank, pulled

himself laboriously against stream through the mesh of branches dipping

into the water.

He was a pathetic

figure. The Peterborough was his home. It was a cramped domicile in very

truth, scarcely 14 feet in length, bobbing like a cork float on the

sportive waters of the turbulent Fraser, and which braved timber-jam

races, rapids, end canyons. In the bow a more or less white heap thrust

its ugly protuberance above the thwarts; this was the paddler’s home at

night —a small tent, housing all his daily requirements in the way of

bedding, cooking utensils, and provisions. He kept paddling upstream

during the day, and when the shades of evening fell he pulled into an

open spot on the bank, made his Peterborough fast by snubbing the

painter round a tree-stump, pulled out his tent, rigged it up, piled a

camp fire, and cooked his meal, which he devoured in solitary state. For

day after day this individual never saw the sight of a human face,

unless it happened to be an Indian on the prowl for game. Even this

interlude was not frequent, because the Indians took good care to keep

out of eyeshot of Roberts, the game-warden. He was as relentless in

driving home his duties as any man of his race to be found between the

poles, and it would have been difficult to find even a hardened hermit

prepared to take on the task of patrolling 350 miles of such wicked,

silent waterway as the Upper Fraser River. He was taciturn, almost to

the degree of being dumb ; probably the silence of the forest had

entered into his soul and had numbed his faculty of speech. lie eared no

more for the progress of the outside world than the cannibal is

captivated by Grand Opera. This warden was marooned worse than any

lighthouse keeper—the latter does have the company of a fellow-being in

his vigil over the watery wastes, and does receive spells of holiday

ashore at regular intervals; but for Roberts there were no such welcome

changes. The only variation he ever enjoyed was when he ran up against

the firewarden of the Upper Fraser, who was almost as great a nomad,

though he had the company of his wife and child in the crazy-looking

dugout.

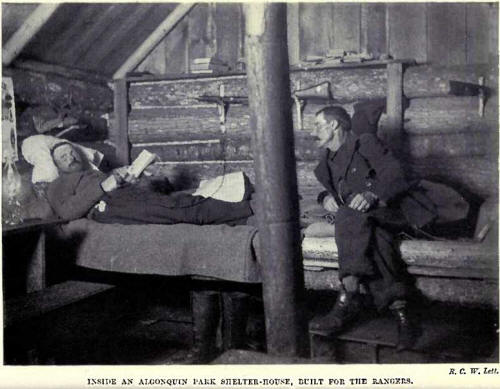

One of the members of

our party on this occasion, Mr. Robert C. W. Lott, a few years before

had thrown in his lot with these lonely patrollers, for the purposes of

restoring his health. The scene of his activity was in Algonquin Park,

some way up in the Highlands of Ontario, and he painted me some very

powerful pictures of the life of this official under all varying

conditions. Twenty five rangers were responsible for the maintenance and

safety of the animals within this reservation. It seems a small staff in

all conscience, especially when it is recalled that this is one of the

most popular holiday resorts in Canada. The salary at that time averaged

£8 per month, out of which the men were required to board themselves.

This does not appear to be a princely remuneration, but it must be

remembered that living cost only £1 per month. The wages have since been

increased, the present scale being £10 per month, while the board is

approximately the same; but after the latter expenditure has been

defrayed, there is practically no other outlay beyond tobacco and

clothes, which, in view of the character of the work, do not constitute

a very heavy drain upon the financial resources of the wage-earner. He

can safely anticipate putting by quite 50 per cent, of his income under

normal conditions of living. In addition, each ranger was entitled to

one deer, which was “cached” late in the autumn to provide an ample

supply of fresh meat during the winter. After the animal had been

slaughtered, the offal and parts unfit for human consumption were saved

to be sacked with strychnine to be used as bait for the large and

ferocious timber wolves, which ravage the park, causing widespread havoc

among the deer.

During the summer, life

as a game-warden in such a park is enviable to those compelled to drudge

in the suffocating and broiling city, because the men spend the whole of

their time in the open air; which, bearing in mind the situation and

altitude of the reserve, is a most invigorating tonic. Hotels have

sprung up at points in close proximity to the Grand Trunk Railway which

traverses this national demesne, and during the hot season these

hostelries are crowded with visitors. The latter hail with delight an

opportunity to get back somewhat to the primitive, and indulge in canoe

and other excursions through the park, leading a more or less rough life

in tents., or shaking down in the log shelter-huts placed at various

points for the benefit of the wardens. Trails have been driven in all

directions, many of them leading through lonely and rugged parts of the

reservation, where a person without a guide may be easily lost, to pay

the penalty for his temerity in essaying to go out alone. Guides are

available, however, to steer the tourist through the loneliest, and be

it noted, most picturesque corners of the enclosure, and it must be

admitted that it would be difficult to conceive a more enchanting

holiday than a sojourn in this stretch of primevalism, for one may

wander over the 2,000 odd square miles for weeks, and not see

half-a-dozen human faces.

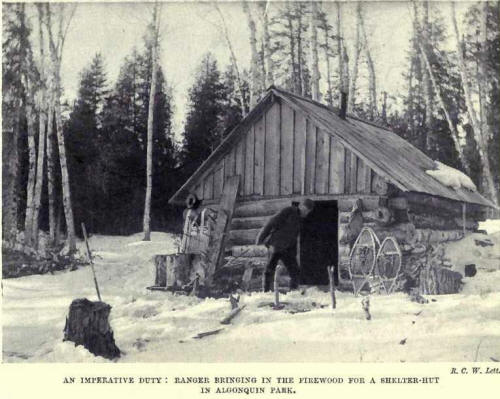

But winter paints quite

a different picture. The rivers are frozen up, and the ground is covered

to a depth of 3 feet or more of snow. The biting northern winds howl

among the trees, and the blizzards rage with terrific fury. The hotels

are shut up, and a general atmosphere of desolation rests upon

everything. Though the country apparently is closed, the wardens have to

be up and doing, as the poacher is on the alert for beaver, mink, and

other animals, which he knows thrive in abundance within this sanctuary.

To them the chances of securing a good big bag are far more rosy than a

quest in the forests beyond the limits of the park. The poacher is a

wily individual. He sets his traps in the most impossible situations,

and moves to and from the scene of his illicit actions by ways and means

which are dark and difficult to follow', taking extreme care that he

shall leave no foot-marks in the snow which might lead to his undoing.

In addition there are the wolves preying on the deer, which have to be

handled. These animals, like the human poachers, have instinctively

learned that a prolific feast awaits them within the borders of the

park, and they ravage the herds accordingly. The wardens give these

parasites very short shrift, resorting to every artifice, no matter how

questionable it may seem from the humanitarian point of view, to rid the

deer of this implacable enemy.

The wardens can relate

many interesting and exciting adventures with this beast, when maddened

by hunger to a degree of extraordinary ferocity. Also, life in the park

offers many golden opportunities to study animal life at close range;

indeed, this constitutes one of the most interesting occupations among

the wardens to while away the time. Lett related how one night, during a

short stay at one of the little cabins specially provided to shelter

them on their rounds of duty, they heard the peculiar cry which betokens

that the chase is on, and that a kill is certain to ensue. In the

morning he and his companion started out in the direction from which the

wail had been heard the previous night. They soon picked up the trail of

the pursued and pursuing animals. The wolves had scented a deer browsing

among low-growing cedars, which is this animal’s most delectable dainty

in winter. Sighting their quarry, they had given vent to a loud howl.

The deer, startled, had broken cover to make for the water, which is its

instinctive act when disturbed. It was a buck, and the chunks oi flesh

and masses of hair which the two men found scattered over the white

cloth covering the frozen lake, plainly told the tale and the vicious

character of the combat. In the chase the wolf is relentless; it springs

upon its prey, seizes the inside of the flank with its teeth, and holds

on like grim death until it tears a mouthful of flesh from the hunted

animal’s body or is forced to release its hold. The men measured the

bounds of this deer, and found them to vary from 15 to 18 feet in

length, while here and there the snow was churned up and darkly stained,

showing where a wolf in his spring had alighted upon its prey, and had

been bodily dragged along for considerable distances. By following the

spoor, the two men at last came upon the scene of the deer’s last stand,

and found its mutilated carcass. The wolves, after they had despatched

their game, had left it, devouring only about 10 pounds of the body,

though they had lapped it dry of its life’s blood by biting into the

throat. Where the wolves wreak such havoc is that frequently they hunt

the deer merely for the excitement of the chase, and the desire of

killing. During this winter pdone, these two wardens found no less than

twenty-two animals which had been killed by wolves, and in every

instance only a small portion of the dead animal had been devoured.

Under such circumstances it is not surprising that the wardens wage a

bitter, inexorable warfare against- the timber wolves. When mutilated

carcasses of their prey are discovered, the abandoned flesh is heavily

soused with strychnine and distributed. Sooner or later the bait

completes its deadly work, though, unfortunately, in the effort to

exterminate the wolves, many innocent foxes, ravens, whisky-jacks — as

the Canada jay is colloquially called—-and blue jays meet an untimely

death by partaking of the poisoned food.

The wardens move hither

and thither through the park in pairs. This precaution is taken in the

interests of safety, not from fear of the wolves, but in case one man

may meet with an accident or be stricken down by illness. In summer the

canoe constitutes the principal vehicle for carrying the requirements of

the men, as the numerous waterways intersecting the park afford access

to the most remote corners. In winter sleds have to be used, and it is

no light undertaking hauling a heavy load of impedimenta over the rough

ground or through the soft snow. At times the wardens experience

hardships of excessive magnitude, battling with the elements or other

adversities which rear up at every turn. Lett and his companion on one

occasion were making painful tracks for their little cabin near the

height of land in the park. Each hauled an Indian sleigh by means of a

pair of traces, relieved now and again by a head or shoulder strap. The

loads upon the sleighs were heavy as the vehicles were well piled up

with provisions, sleeping-bags, cooking utensils, axes, and a few other

necessary odds and ends. It was the coldest period of the season, and

for three weeks the twain had been making towards the little

headquarters on the North River, which is the head-water of the Muskoka

watershed. The weight of the sleighs and softness of the snow alone

would have rendered travelling arduous, but when a rough, undulating and

Limber-strewn country was encountered into the bargain, advance was

rather a series of laborious pulls, blind stumbling, and back-racking

falls. The day was rapidly closing, and the cabin was almost in sight,

when they reached the bank of the North River. This waterway had to be

crossed, as the shack was on the opposite shore; but the question was,

How to cross the river. They had half hoped, in view of the low

registering of the thermometer, that the water would be frozen

sufficiently to enable them to cross on the ice, although they were only

too cognizant of the treacherous character of this waterway. It is one

of those rivers which is so rough, and rises and falls so quickly that

it is perilous to cross hi winter, as its ice is rotten and unsafe; but,

to their dismay, when they reached the waterside, the river was quite

open and tearing along fiendishly.

They were in a

quandary. They had no canoe, and there were no dead dry trees handy with

which a raft might be fashioned. Yet they bad to get across that night

somehow or other. They stacked their sleds and rummaged tho adjacent

forest for tho slightest signs of any wood that might be serviceable for

a raft. After much search and considerable time they found six short

logs. These were dropped into the water, and a few pieces were laid

transversely to hold the fabric together. While his companion turned

into the forest to find one more piece of wood, Lett, thinking the crazy

craft perfectly safe, stepped aboard with the pole to make the crossing.

Unfortunately his moccasins were quicker than he himself; the frozen

soles, coming info contact with another icy surface on the logs, shot

bis leg;; out on either side, spreading the logs and letting him through

the hole into freezing water up to his shoulders. Fortunately some

bushes -were overhanging the waterway, and as he dropped into the water

Lett gave a mad clutch at them, thereby preventing the swinging current

throwing him into midstream, where swimming would have been of no avail,

owing to the velocity of the water and its icy coldness. At this

juncture his companion returned, and when he looked down to where the

raft had been improvised, he was so surprised to see nothing but Lett’s

head and shoulders, that he dropped his log. Lett brought him to his

senses by asking for a hand out. Dry land regained, Lett shook himself

as well as he could, and with his clothes freezing upon him, the

scattered logs were regained and the raft re-fashioned, only this time

some rope was taken from the sleds to bind the slippery wooden pieces

together. The second warden, being a smaller and lighter man, embarked

upon the raft this time, poled himself safely across the waterway, and

then hurried to the cabin to drag out a small canoe to bring Lett over,

the latter meanwhile endeavouring to keep his circulation going in

freezing clothes by violent exercise. His companion was certain that his

immersion would result in a, fatal illness, but it is the luck of the

bush that colds are seldom contracted from such duckings so long as one

keeps on the move. When the log-hut was gained, a roaring fire soon

dried the drenched garments, and restored the warmth to the unfortunate

warden’s shivering body.

The fire-warden’s

duties, possibly, are even more strenuous. He is ever on the roan, with

a keen eye for the slightest outbreak of the fire-fiend, which wreaks

such widespread damage among the timber wealth of the country. When the

summer is hot and dry, his life is an exciting and exhausting round of

toil. Ho may be out for days and nights fighting a bush conflagration,

summoning assistance whence he can. He has the authority to call upon

one and all who chance to be within hail to help him in his task.

Refusal is criminal, and brings a heavy fine with possible imprisonment.

Travellers through a country are sometimes dismayed to find the

fire-warden enforcing his authority with all the austerity of the old

press-gang, but there is no alternative ; one must buckle to and lend a

hand. This power has provoked some humorous situations at times ; for

instance, a company of actors had been despatched up-country by an

enterprising firm of cinematograph play-producers to enact a back-woods

play before the camera, the idea being to secure the local colouring to

perfection. While they were in the midst of their work, obeying the

stentorian behests of the stage-manager, a smoke-begrimed and tattered

firewarden burst upon the scene. Every man in the company was ordered to

“quit playacting and to give a hand in putting out the bush fire.” The

actors remonstrated, but in vain. Opposition to the common enemy of the

country was far more important than getting a film to amuse the

thousands in the cities. The warder, hustled them up, threatening to

prosecute one and all with the utmost rigour of the law if they did not

answer his call, and quickly too, as time was pressing, and permitting

the fire to secure a firmer hold. Those performers were kept hard upon a

most uncongenial task for several hours on end, and when their services

at last were dispensed with, they presented a sorry-looking and

exhausted mass cf humanity; then, the most amused individual was the

warden himself, and his laughter provoked threats of terrible reprisals

fur interfering with a lawful occupation. A complaint was duly lodged

with the authorities by the aggrieved artists, together with a claim for

damages, but, laughing up their sleeves, the authorities pointed out

that the warden was acting quite within his powers, and if actors and

actresses were content to penetrate into such a country, they mast run

the risk of the country’s luck. Occupation or social position cannot be

taken into consideration in such desperate circumstances; when the bush

fire is racing the millionaire travelling in the vicinity can be

impressed as much as the unkempt hobo or tramp.

Keeping a vigilant eye

upon the game during the winter and frustrating the knavish tricks of

the wily poacher constitute a welcome interlude to the normal daily

round of the park-keeper. There are a few oldtime trappers still, who

trod the trails intersecting this reservation years before it was ever

railed off for the benefit oi the public, and before the inmates of the

animal kingdom were brought under the protective wing of the Government.

These worthies occasionally forget this latter circumstance, as well as

the situation of the boundary lines, and, wandering within the preserve,

secure a few beaver or mink with their metal traps; but the professional

poacher is far more cunning; he knows the strength of the forces of the

guardians of the animals the fact that they patrol the area in couples,

and that they have an extensive stretch of diversified country to cover.

He also knows their trails and shelter-huts. Accordingly, he steals

through the bush, leaving the paths severely alone, and in this manner

the prints of his snow-shoes are difficult to trace. By gaining asylum

in the dense thickets the poacher is often passed unobserved within a

yard by the rangers, and is able to complete his nefarious work. But

.Nemesis in this instance has a long arm. The warden is at liberty to

arrest any character whom he suspects of poaching within a mile of the

boundaries of the park, and accordingly many a poacher who has secured a

good illicit haul within the reservation has met his deserts beyond the

fence.

The Government is

devoting more attention to the class of men suited for this peculiar

work. Although the life seems terribly lonely, there is no dearth of

applicants. It is excellent training, and the greater number of the

rangers have turned their drifting in the woods to excellent account for

improving their positions in life. It affords excellent scope for

mastering the intricacies of woodcraft, reading and cutting trails,

studying the habits, manners, and peculiarities of wild animals at close

quarters, an well as becoming fitted for detective work. The motto

“Never turn back, but get to your objective at all costs” is the guiding

aphorism, and the men act up to it fully. The life appears to be

selfish, for the only cares presenting themselves to the rangers are

avoiding accidents, patrolling conscientiously, and providing from

Nature’s larder for the next meal. The men enjoy the life thoroughly,

and confess that it leaves nothing to be desired. The call of the wild

becomes so deeply rooted that, although many of the men at times long

for the glare glitter, and bustle of the “Great White Way” of the city,

and abandon the wilderness for commercial activity in civilization's

maelstrom, they invariably return to the tall, silent timbers, within a

few months. |