|

“Now the violet tint was

upon us, but the summit of the mountain was still burnished with a line

of bright gold. It died away,

leaving a lovely red,

which, having

lingered long,

dwindled at last into

the shade in which all the world was enveloped, and left the sky clear

and deeply azure ”

John Auldjo

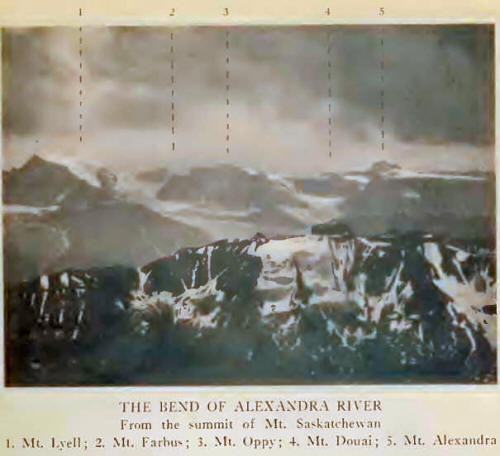

Filling the great angle

between Alexandra River and the North Fork, a thing of towers and

battlements, rises Mount Saskatchewan. Formidable in appearance, and

long sought by climbers, it had never failed to attract the attention of

those who came into the region. A symmetrical monolith on the jagged

northeast ridge is well known as the “Lighthouse,” and serves as a

landmark in the valley of the North Saskatchewan.

We knew the mountain

well by this time. From the east, on the slope of Mount Coleman, we had

gazed upon its unclimbed heights, wondering at its sheer forbidding face

of snow-powdered cliff. The bounding ridges are broken with deep gaps

below the summit and bristle with gendarmes. On the icefield we had

again seen this sky-cleaving wedge and examined its southwestern face,

which, although formidable, offered a more feasible approach. It was

always challenging.

On awakening after our

long and weary journey to North Twin, I found the sun high in the

heavens. Tommy had the fire going and was putting together a tremendous

lunch. From the teepee came intermittent strains of a harmonica, for

which only Conrad could be blamed; and you have missed real music if you

have not heard his orchestrations! This time, however, it sounded as if

he were suffering from sunburned lips. In the direction of Ladd’s tent

there were no signs of life.

A day in camp put us in

good shape again and we were ready for further work. Early on July 12th,

we started up the gradually rising slopes behind camp and made our way

to the low snow-saddle connecting the head of Castleguard with Terrace

Valley. It was just five o’clock; and descending the meadows on the far

side, we were soon in the shadow of Mount Saskatchewan, which rose above

us in outline suggestive of the Matterhorn as seen from Zermatt. We

approached the southwestern face, above Terrace Creek, where a slanting,

subsidiary ridge descending, north of the summit, breaks the face into

an eastern and a western cirque.

Entering the smaller

cirque, which is also the more precipitous, over scree and winter snow,

we came close to a “jolly little company of goat”—five old ones, with

several kids—who scuttled off across a subsidiary ridge to the east and

showed us a route thither. A deep couloir, snow-filled, afforded access

to the ridge; but the goat arrived much more gracefully and rapidly than

we.

We were now on the

crest between the two cirques, and followed it up to the first cliff

belt. Far away through Terrace Valley rose the white, north face of

Forbes and the glaciated range from Thompson Pass to Lyell and

Alexandra. Snow, mist, and sky; partially hidden in cloud, with sunlight

breaking through: the Columbia Icefield revealed itself. We turned for a

moment to watch the goat; after attempting to dislodge stones on us in

the couloir, they had crossed

some higher ledges

to the north and were soon out of sight. A big billy remained behind on

guard. High on a cliff-ledge was poised an enormous boulder; behind this

he went and was quite hidden. But every once in a while we could see his

bearded face poke out through a crack; he was quite curious about us and

we found him very amusing, the entertainment undoubtedly being mutual.

Through slabby

chimneys, where little showers of icy water came down; up bits of broken

cliff, traversing eastward, we found cracks which led upward. The first

belt, about forty feet high, was surmounted at a point nearly a hundred

yards east of the rock crest between the cirques, and we crossed some

steep bits of snow on the way thither. Under the second line of cliff,

we again traversed eastward before finding a suitable break. On a small

buttress we built a direction cairn to guide our return, and as a

possible service to future climbers. A short distance farther east, we

reached 10,000 feet at a point below and north of the summit. Then

followed long slopes of wet, down-tilted scree and shale, leading to

steep pitches of snow by which the arete was eventually gained. It was

hard work, but the cliffs were well covered, and only once or twice did

small superficial avalanches go down behind us.

In the Italian valleys

of Monte Rosa, there is an ancient legend of a “Lost Valley”; and, just

as the peasants of days gone by may have looked over to the unknown

meadows of Switzerland, so we gazed from the precipitous north face of

our mountain. It was 2.40 P. M., and it became apparent that the point

we had aimed for was not the highest, but that the true summit lay

several hundred yards farther east. To reach it, due care and attention

were given to the cornices overhanging on the north; but with some

step-cutting and a final bit of rock scrambling we reached the top.

North Fork and

Alexandra River meet in a broad sunlit angle; with care, we looked down

the wall to the lighthouse pinnacle, now almost under us. Peaks,

icefields, and glaciers were all about us. We built small cairns,

leaving a record of our North Twin ascent as well—there had been no

visible rock outcrop on its summit—and started down again at just

halfpast three.

On descending, we had

scarcely gotten off the steep snow, when a thunder-shower overtook us.

We crouched in a corner until its violence had passed, and then with

speed were down the rocks and glissading in showers of spray to the

meadows below. We stopped and finished what remained of our provisions,

and strolled homeward over the snow pass. All the western peaks were

aglow with the radiance of sunset; we were refreshed, carefree, and

happy. Without hurrying we arrived in camp at nine o’clock, satisfied

beyond expression that we had been the first to ascend a mountain whose

impressive and imposing architecture had for years excited our

admiration.

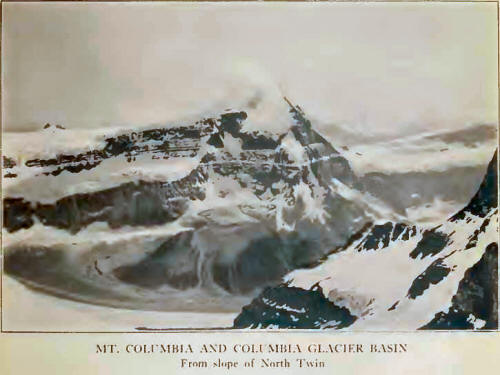

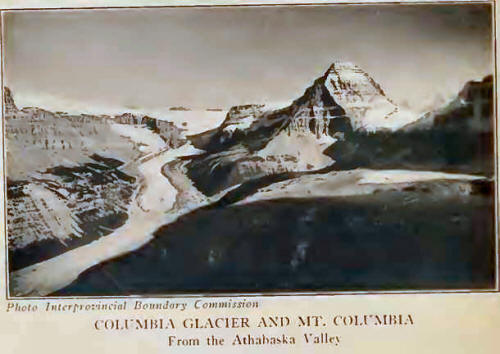

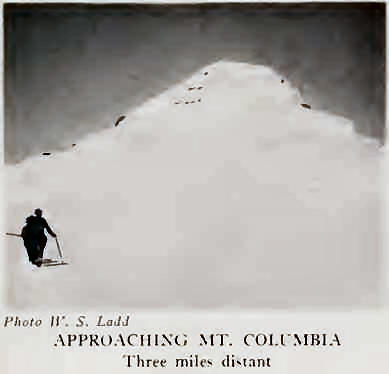

Mount Columbia, the

despotic, white monarch of the icefield, on occasion—with an oft-worn

crown of storm and mist removed—assumes an aspect more benign, although

always serene and majestic. From the north, in the gorge of the

Athabaska, its elevation is best appreciated. It was from the depths of

this valley that the German explorer, Habel, in 1901, saw it and named

it “Gamma.” He was misled by its appearance as a rock-pyramid, and

failed to identify it as the rising, soaring snow-peak which Collie had

described.

Even from the level of

the icefield, at 10,000 feet, Columbia merits its proud position as the

second elevation of the chain. It had seemed so far above our heads when

we were on Castleguard, we wondered if we should ever reach it. But on

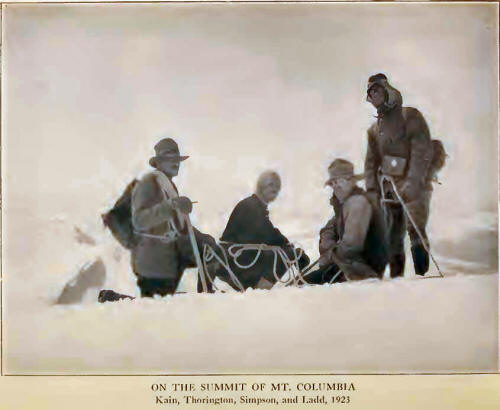

July 14th we started out. The climbing party derived added pleasure from

the presence of Simpson; Jim had been with Sir James Outram and the

guide Christian Kaufmann, but had not climbed, at the time of the

first-ascent, in 1902, just twenty-one years before. Reaching

Castleguard shoulder (3.50-5.30 A. M.), we found the snow in fine

condition and rapidly traversed the tracks made some days previously.

Morning sun was gilding

the ranges; the wind blew forcefully, and we turned toward Columbia,

gleaming in the ice-blue of clear weather distance. Insects innumerable

are carried up onto the ice by air currents from the British Columbia

side; and, at 10,000 feet and above, we collected moths and beetles of

many varieties. One might have some difficulty in obtaining such numbers

at lower elevations; many were still alive, although torpid from cold.

They form the food supply of snow-finches which one sees wheeling and

darting about.

Although favorable

conditions of snow made travel more easy than on our tour de force to

The Twins, we again had to cross many gaps and deceptive, crevassed

hollows. Far out on the icefield, shortly after ten o’clock, we had

lunch on the flat snow above the head of Columbia Glacier. The snow

cirque of the glacier is encroaching on the head of the basin dropping

to Bush Valley; a deep, broken snow pass is formed, which, in years to

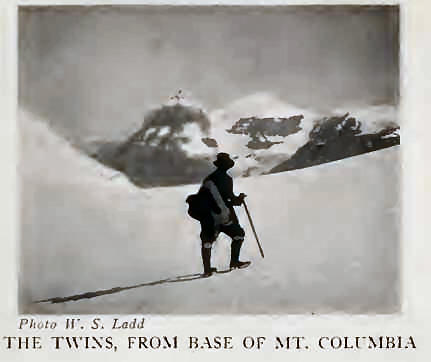

come, may isolate Columbia from the icefield. In similar fashion, The

Twins are being cut away from the field through the “plucking” of the

Columbia Glacier basin against the glaciers descending to Habel Creek.

Sun-glare, reflecting

from the high snowfields, may produce severe burns equal to any

resulting at the seashore, and we were glad enough to protect our eyes

with goggles and cover up blistered faces. Thirst is unquenched by the

eating of snow; there is practically no water on the entire icefield,

and, on this climb, we had learned the lesson to carry a small amount

with us.

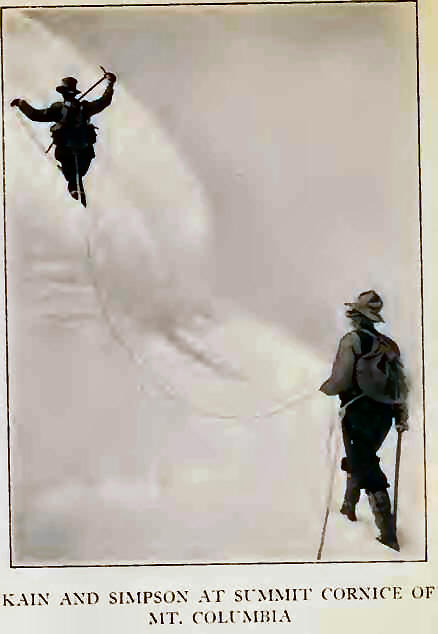

We were soon at the

bergschrund, a narrow chasm easily crossed, and on steeper snow beyond.

At 11,000 feet we halted by a rocky outcrop where water trickled; we

were in the centre of and more than half way up the great eastern

snow-face, practically treading the Continental Divide. We wondered what

the other outfitters would have said if they could have seen Jim with an

ice-axe, roped in a climbing party? The pitch steepened; steps were

occasionally cut; a stinging, relentless wind tore up the snow-crust

until the air seemed full of whirling white shingles. We toiled upward

for some time in the gale, in some danger of having snow-glasses broken

by bits of flying ice.

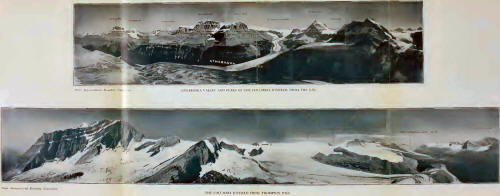

Edward, Mount

Clemenceau loomed in the Wood River area; across the haze of the

Athabaska Valley, beyond South Twin, the mountains toward Yellowhead

lifted in splendour undiminished by distance. In the direction of

Maligne Lake, jagged peaks, of lesser elevation, were dazzling in the

gleam of new snow. Mount Alberta and Mount Bryce, respectively north and

south of us, were things of primitive beauty, distracting attention from

all the rest: Bryce, rising in snowy heights one above the other, with

avalanches falling from its savage northern face; Alberta, cliff-ringed

and austere, its head aloof and wreathed in cloud. Lyell, Forbes,

Freshfield, and a host of others towered gloriously.

The wild gorge of Bush

River can be traced nearly to the Columbia; the Saskatchewan, across the

icefield, flows eastward between Mounts Wilson and Murchison to find

exit to the plains; into the north, one follows the course of the

Athabaska. One retains of it all, chiefly a memory of river

valleys—streams sparkling in the sunlight—winding on their long journeys

to distant oceans.

Forty minutes we spent

on the summit, and fifteen more, out of the wind, on a level spot below

the cornice. The top of Gamma! Let no one think that Columbia is a mere

snow-hump rising from a neve; it is a distinct peak in every sense,

looking its height and quite worthy of its place. Simpson intends to

climb it every twenty-one years from now on!

Softened snow permitted

a rapid though cautious descent, a final long glissade carrying us to

the icefield. Return to the Castleguard shoulder was made in good time,

although we delayed in watching the sunset. The icefield was an empire

of silent purity, brilliant in golden sheen; a rosy haze filtering down

through the Selkirks, lifting them to unearthly heights.

In a little while we

were back at the campfire; just six hours from the summit. We had supper

by the crackling logs, with the cross-lights from fire and western

afterglow. The shadows lengthened, blue-black at the forest edge, and

Conrad told us stories until there was no light remaining save that of

the glowing embers, and the stars that peeped out above our heads.

|