|

“The man who can

drag himself up a vertical rock face when he can just get the

finger-tips on to one little ledge, will be of far less use in an

exploring party than the man who can judge quickly the state of snow”

Clinton Dent

The Freshfield Group

was the goal of the Expedition undertaken, in 1922, by Howard Palmer,

Edward Feuz, and myself. We had come from Field with Jim Simpson, over

the Howse Pass trail; a route followed by David Thompson1

of the North-West Company as early as 1807—Joseph Howse, clerk of the

Hudson’s Bay Company, did not begin to use the pass until two years

later—and for four years ensuing, until hostile Indians of the western

slope forced the traders to turn to Athabaska Pass in crossing the

Continental Divide.

There seems to be no

mention of the Freshfield Group until 1860, when it was visited by Dr.

Hector, of the Palliser Expedition, while searching for the northern

approach to Howse Pass. He writes,2 “At

daylight I started with Beads to see where the valley leads to, and

after five miles through very thick woods, we suddenly emerged at the

foot of a great glacier [Freshfield Glacier] which completely fills the

valley, and showed us that there was no hope of getting through with

horses by this route. We ascended over

the moraines, and had a

slippery climb for a long way to reach the surface of the ice, and then

found that it was a more narrow but longer glacier than the one I

visited the previous summer [Lyell Glacier]. The upper part of the

valley which it occupies expands considerably, and is bounded to the

west by a row of high conical peaks that are completely snow-clad. We

walked over the surface of the ice for four miles, and did not meet with

many great fissures. Its surface was also remarkably pure and clear from

detritus, but a row of large angular blocks followed nearly down its

centre. Its length I estimated at seven miles, and its width at one and

a half to two miles. By three p. m. we had returned to our halting-place

of yesterday, and now proceeded to try Beads’ valley.

“For three miles we

followed up the stream to the south, until we found that it suddenly

rose from a glacier [Conway Glacier] in a high valley to our right.

However, as the valley before us continued to look wide and spacious,

with a flat level bottom covered with dense forest, we left the river

and continued a southerly course, sometimes seeing little swampy

streams, which showed us that the water was still flowing to the

Saskatchewan. After about three miles we observed a small creek issuing

from a number of springs, to flow in the direction in which we were

travelling; but we could hardly believe it to be a branch of the

Columbia, and that we were now on the west slope of the mountains,

seeing that we had made no appreciable ascent since leaving the main

Saskatchewan, and had encountered nothing like a height of land. We

camped here beside a small lake and beautiful open woods, where the

timber is of very fine quality.”

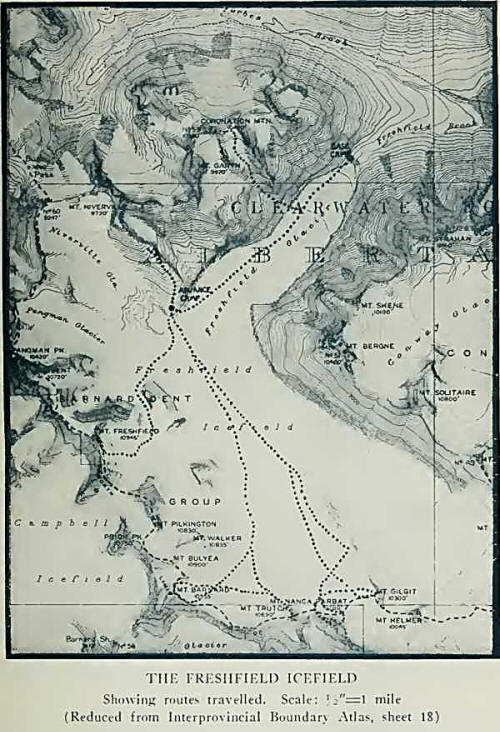

The Freshfield Group is

situated on the Continental Divide, in latitude 51° 39' 51", between

Howse (5010 feet) and Bush (7860 feet) Passes, an air-line of some ten

miles; although, due to the southwesterly bowing of the watershed

between the two passes, the actual crest of the group is much longer.

Howse Pass lies nearly a hundred and twenty miles south of Yellowhead

Pass; and in 1881, the year of chartering the Canadian Pacific Railroad,

it had been decided to abandon it in favour of the Yellowhead route,

since the latter afforded a lesser gradient. It was felt, however, that

a more direct route to Kamloops could be found; and, when in the

following year the practicability of Rogers Pass across the Selkirks’

summit was ascertained, the railroad was finally diverted to its present

location in Kicking Horse Pass. The Howse Pass is perhaps forty miles

from Kicking Horse, but the distance by trail from Field to the

Freshfield tongue is more nearly sixty-five miles. Between Howse and

Athabaska Passes—less frequented than in olden days—there is no

intervening gap in the Divide through which horses can be taken; the

western slope is steep and heavily forested, while the valleys, draining

to the Columbia, through Bush River, are unsuitable for travel

paralleling the main range.

On the western side of

the Freshfield Group, the Campbell Icefield forms a chief source of the

south fork of Bush River, draining to the Columbia. The Freshfield

Icefield itself, some twenty square miles in extent, fills the eastern

cirque, and discharges by a single tongue, three miles long and

three-quarters of a mile wide, its stream being an ultimate source of

Howse River.

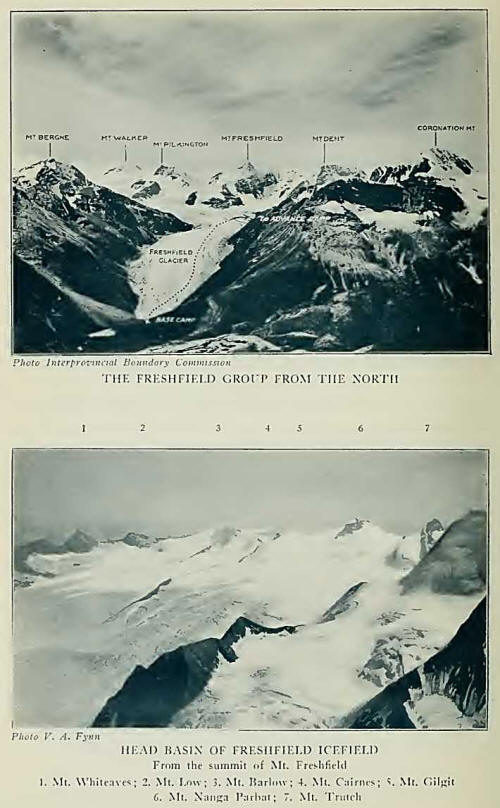

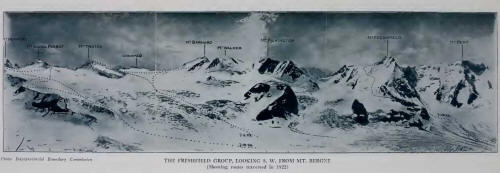

The chief peaks of the

group lie on the Divide, subsidiary ridges extending east and southeast

to enclose large glacier cirques, of which the Conway, Lambe, Cairnes,

and Mummery are the most extensive. In the group are approximately

thirty peaks of importance, of which at least twenty-four exceed 10,000

feet in altitude. The watershed summits are chiefly snowy peaks; those

on the subsidiary ridges of the eastern wall are scarcely of lesser

height, but generally more rocky in appearance.

Climbing parties in

this region have been infrequent, chiefly because of the distances

involved. In 1902,3 an Anglo-American party

consisting of Messrs. Collie, Outram, Stutfield, Weed, and Woolley, with

the guides Hans and Christian Kaufmann, made the first-ascent of Mount

Freshfield (10,945 feet). In 1906, with Gottfried Feuz and Christian

Kaufmann, Messrs. Burr, Cabot, Peabody, and Walcott ascended Mount

Mummery (10,918 feet), from a camp in the upper Blaeberry Valley. Eaton

and Marocco, with Heinrich Burgener, came out from England in 1910, and,

from camp at the Freshfield tongue, traversed Mounts Dent (10,720 feet)

and Freshfield, over the intervening, unnamed snow-dome. They likewise

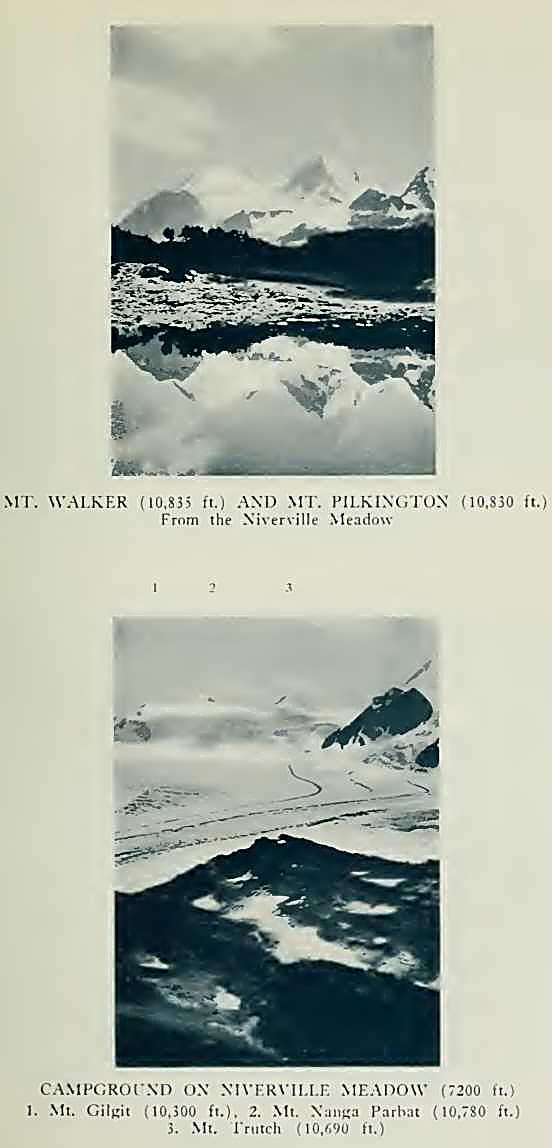

made first-ascents of Pilkington (10,830 feet), Walker (10,825 feet),

and a snow peak on the Divide, south of Pilkington, for which the name

“Burgener” was suggested, but which has since been named Mount Bulyea

(10,900 feet). During 1917, the Interprovincial Survey occupied a number

of high ridges and summits, including Bergne (10,420 feet), and Lambe

(10,438 feet). In 1920, Messrs. Eddy, Fynn, and Mumm, with Rudolf Aemmer

and Moritz Inderbinen, made the third ascent of Freshfield. Other

climbers who have reached the group accomplished little or nothing

because of bad weather.

In 1922, Howard Palmer

and I had the good fortune to visit the group, with Edward Feuz as

guide, and make a number of ascents. On the new map of the Survey, we

discovered that there was a peak on the Divide—Mount Barnard (10,955

feet)—higher than Freshfield and, therefore, the loftiest of the entire

group. Barnard lies south of and hidden by the Pilkington-Bulyea ridge

and is quite invisible from the glacier-tongue. The difference in height

between it and Freshfield is not great, and these facts explain in part

why the mountain had for so long remained unattacked. We determined to

make it our objective.

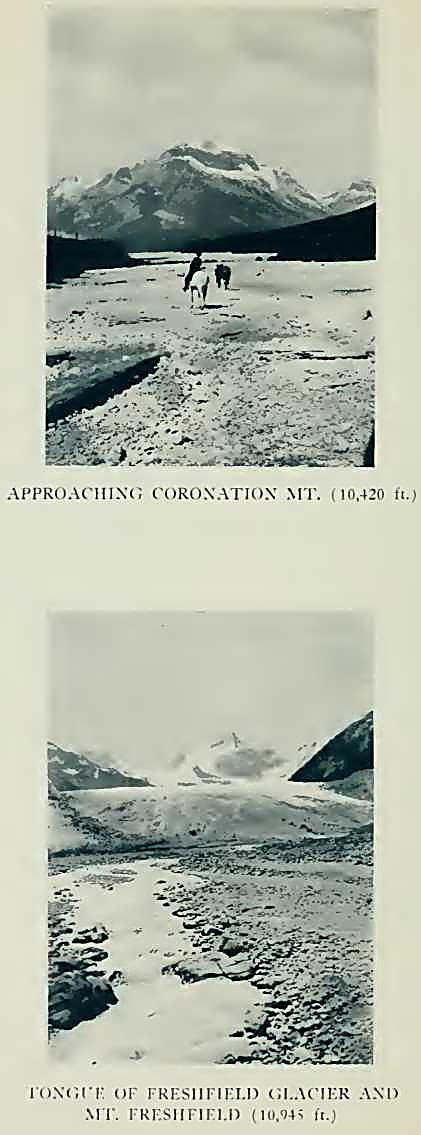

We had come from Howse

Pass on July 10th, a short ride down Conway canyon to the lower flats,

and thence up trail through forest, rising sharply and emerging on a

morainal terrace with the broad ice-tongue close at hand and Mount

Freshfield, southward, rising to a slender peak. A grassy slide nearby,

gay with columbine, paintbrush, and forget-me-nots, affords a welcome

feeding ground for the horses. Strangely enough, good grass is

exceedingly scarce between Field and the upper Blaeberry, and there had

been many long morning searches for wandering cayuses.

A glacier never fails

in its fascination. The snout where the milky stream begins, is the

balancing point in the battle between onward motion and dissipation.

Most glaciers are retreating, slowly but steadily, although such changes

are cyclic and advance may someday begin. About the tongue are blocks

and boulders, weighing tons, carried down from higher points, in

moraines, and left behind as the ice retreats. Were it not for their

slow motion, glaciers would be among the greatest of natural

transportation agents. The glacier surface is often flat and easy to

walk on; but ice is not perfectly plastic, and, where it moves over

declivities, crevasses and chasms are formed, with blue walls and

toppling pinnacles. Little surface streams from melting ice rush down,

banking and swirling in their frozen canals, eventually to disappear in

the depths of crevasse or moulin, which Dr. Hector noticed, are

scattered about, although they have moved some distance in the

intervening time; the snow-covered conical peaks—Walker, Pilkington,

Freshfield, and Dent—remain unchanged. The huge upper snow-basin, from

which, as from the neck of a bottle, the glacier-tongue extends, is not

seen in its entirety until one travels some distance up the ice. The

basin receives snow from the magnificent curve of watershed peaks: there

are broad, undulating slopes from the peaks eastward toward the

Blaeberry; a higher level of icefall and plateau from the south, from

Nanga Parbat to Dent; and, from the direction of Bush Pass, smaller

glacier-tongues, which, in retreat, have disconnected from the icefield.

From a few of the

peaks, rocky buttresses with peninsulas of meadow push out to the

glacier margin. It is quite easy, as we found, to back-pack up the ice

and make camp on such a spot. On July 11th we reached a heather-covered

alpland, below Mount Niv-erville,4 pitching our

tent' beside a tiny brook, with banks of spring snow still remaining.

There were trees, but dwarfed and twisted by storm. Flowers everywhere,

as never seen at a lesser elevation; and, at sunset, the snowfields and

mountain tops lighted by a procession of colours, ethereal and baffling.

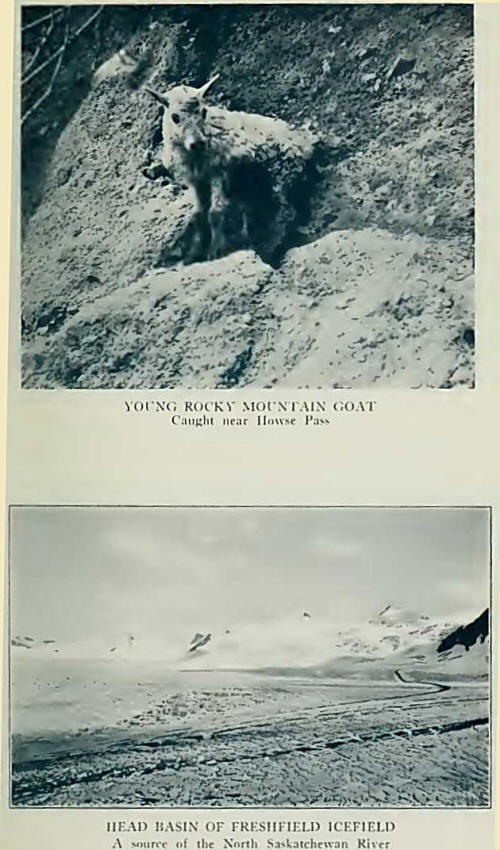

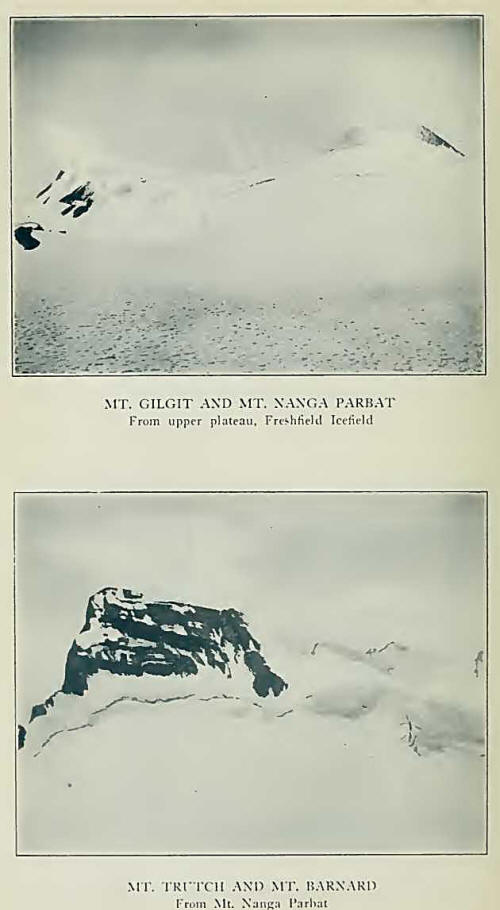

The icefield may be

roughly divided into three sections: an icefall basin, descending

between Dent and Walker; an upper snow-basin, rising high up on Walker,

extending southward to Mount Barnard and eastward to the snowy dome of

Gilgit (10,300 feet), where it drops off in cornices and cliffs; and a

lower head-basin descending from the slopes of Mount Barlow (10,320

feet), and adjoining peaks, and connecting with the other divisions in a

series of icefalls and flat ice-areas that eventually form the

Freshfield tongue. From the minor peaks on the south side of Bush Pass,

the Niverville and Pangman Glaciers descend into the Freshfield basin,

but are at present only loosely connected with the icefield. The

Niverville stream runs under the Freshfield ice, while a subsidiary

pressure tongue of the Freshfield basin actually faces up-stream toward

the Niverville tongue. Much of the upper ice is stagnant, with surface

drainage incomplete, and in the late afternoon the ice is covered with

water, in some places to a depth of six or eight inches. Our high camp

was a fine place from which to see the long sinuous medial moraines,

trailing back for several miles to the promontories in which they

originate.

Climbs from the high

camp were made on the days that followed, with intervals during which we

occupied ourselves with a survey of the glacier-tongue and a rough study

of the ice movement. On July 11th, Edward and I put out a line of

stones, 1100 yards above the ice terminus, Palmer lining them up with

the transit and signalling to us from a station on the western lateral

moraine. The width of the glacier is here 1000 yards; our fourteen

stones, at one-hundred-and-fifty-foot intervals, were remeasured on the

morning of July 19th, after a time period of six full days. We

calculated the motion as being between four and five inches per day,

which is in agreement with the July movement of other glaciers on the

main chain.

On the first medial

moraine east of the central axis of the glacier, Jim and I found a small

area, near the base of Mount Skene (10,100 feet), where there are

curious clusters of iron pyrite, many of them larger than a golf-ball,

riding free on the ice surface. This deposit was observed in no other

location except for a small bit picked up in the Garth-Coronation gully

just below the hanging glaciers. The immense boulders in the medial

moraines are remarkable for their average large size. Some are as big as

a bungalow, and afford amusing climbs. The largest of all on the ice was

ascended by Edward, who built a little cairn on top. The occurrence of

such enormous boulders appears to be related to the so-called “Block

Moraine,” supposedly due to ancient seismic disturbance.

On the southern wall of

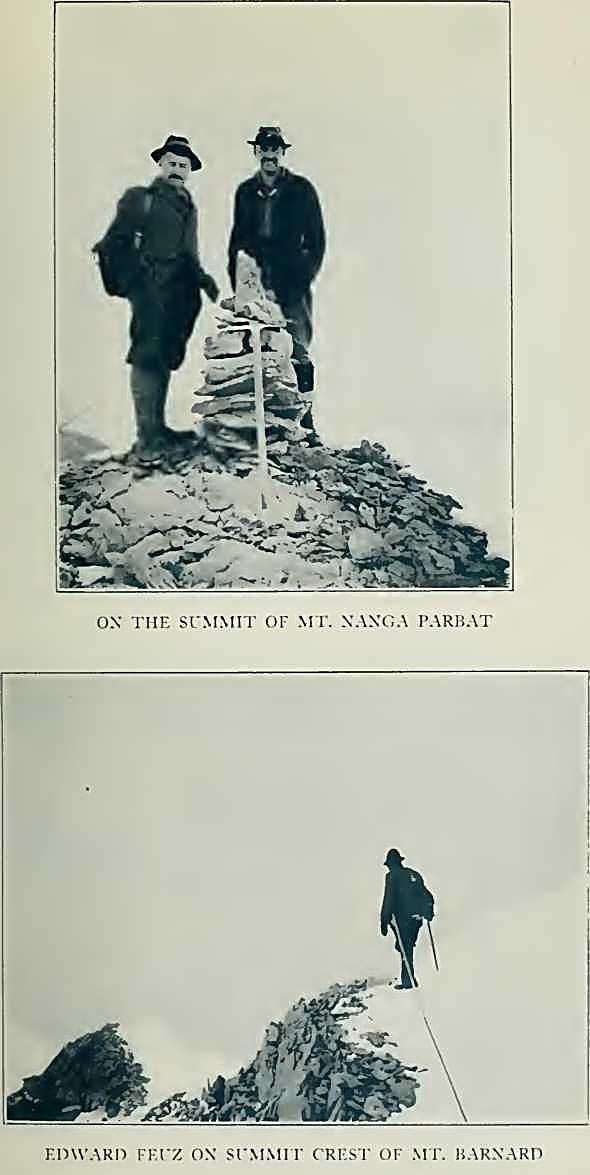

the icefield were situated our objective peaks. On July 14th, we were

successful in making the first-ascent of Mount Barnard,9 loftiest summit

of the group. With an early start, we descended slopes of grass and

shale between our little camp and the ice. We were in shadow, but rosy

light, striking through the mist-bands clinging to the cliffs of Mount

Solitaire, diffused across the upper snows and came down to meet us as

we walked along.

Dawn, on a glacier,

often comes silently. Streams have almost vanished, and resume their

turbulent rushing only when sunlight again falls on their sources. The

crags and buttresses, from which trail long winding moraines, seem close

at hand. But distance, on snow and ice, is deceptive. The moraines are

here flat and compact, yet not so royal a road as the level ice. We

advanced four miles without difficulty, jumping over smaller crevasses

and deviating for larger ones.

Not many hours passed

before we reached an elevation at which snow covered much of the ice,

concealing the crevasses and making the use of the rope a necessary

safeguard. We were soon in a labyrinth of crevasses, which we threaded,

cutting steps, or crossing by firm snow-bridges from which hung shining

icicles that dripped water into blue depths and darkness. No sounds save

the bell-like tinkle of water dripping against the ice, and the faint

whisper of an early morning breeze sweeping up the slopes—a near silence

broken by Edward, admonishing us to walk like cats and by no means to

jump on the snow-bridges. There were places where we balanced like

acrobats, on the crests—Edward dubbed them “garden-walls”— between two

crevasses. Huge things those crevasses were: some nearly a hundred feet

wide, quite equal to that in depth; and, curiously enough, snowed up

flatly and solidly at the bottom. One could have roped in and walked

around for some distance.

Then, from a higher

plateau, we gazed upon our long-hidden mountain. White and gleaming it

was, lifted up in the haze of distant forest-fires in British Columbia,

until it seemed to touch the sky. Crossing a mile of flat snow, we

reached its base at the eastern end. The northeast face is snowy and

broken by large schrunds, and here was the only visible point where they

were sufficiently bridged to allow of crossing. We tackled a wall of

steep, soft snow, above a tiny bergschrund, moving cautiously and

anchoring deeply, slowly but surely to the main arete. It was not done

in a moment.

A high wind tugged at

the rope as we walked along the ridge, and we were glad enough to pull

our caps down over our ears. Vast ice-basins lay below us, snow slopes

falling steeply on the north; while unbroken couloirs, partially

ice-filled, curved giddily to the southern and western glaciers. Far

ahead, rising above an ascending succession of lesser snow-blown crests

of the ridge, gleamed the slender, highest point. Two hours were spent

in following the ridge; the ice-axe came more frequently into play;

speed lessened. A last bit of cutting in the ice of a couloir-head

brought us to the base of the snow-spire, and in a few minutes we were

on a summit scarcely big enough for the three of us at once. It is good

to be alive at such a moment, and, for a time only too short, stand as

the little monuments of such a glorious pedestal.

The highest summit of

the Freshfield Group was ours. At a quarter to eleven we had attained

its respectable elevation of 10,955 feet, in a little less than seven

hours. While distant views were somewhat obscured by smoke, the sheer

drop on the south and west to the Campbell Icefield was always

spectacular. We built a little cairn and ate our lunch; then retraced

our steps back along the ridge until the sharp arete descending

northward toward Mount Bulyea could be reached. The snow was in good

condition and we made our way rapidly downward. A sudden gust of wind

snatched Palmer’s hat and sent it sailing through the air. For a

thousand feet it went before touching the snow, finally spinning down a

steep slope and coming to rest. We soon glissaded down to the basin

eastward, finding the hat almost in our path; not often is head-gear

blown down from a mountain-top into a glacier basin and found again!

The day was not far

advanced, lacking still a halfhour until noon. Finding ourselves close

to the base of Mount Trutch (10,690 feet), we decided to ascend it as

well. Peculiarly wedge-shaped, this fin-like peak of the Divide had

attracted our attention from camp. Like Barnard, this mountain is named

for a past Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia;9

and so there is a mixed nomenclature superimposed upon a group that

Collie, its first visitor, had attempted to preserve for prominent names

of the Alpine Club. On the northeast face of Trutch is a steep hanging

glacier, while on the southwest a cliff descends to the snow-basin. A

single northwest arete rises like a ridge-pole to the summit, followed

by a sheer drop to the ice. The arete itself is of shale and snow,

presenting no great difficulty; but the last four hundred feet,

invisible from below, turned out to be a knife-edge of rock, which had

to be straddled and took a good hour to negotiate. On the summit, at two

o’clock, we piled up a few stones to commemorate our visit. Ten hours

had elapsed since starting; not often does one make two first-ascents

above 10,000 feet, in a single day! There was no alternative route but

to retrace our steps; so we faced about, reached the snowfield, and

tramped back to camp feeling that our day had been a successful one. We

had travelled about fifteen miles on the ice.

To the east of Trutch

rises the symmetrical, snowy peak of Nanga Parbat (10,780 feet), and

farther eastward, the dome of Gilgit (10,300 feet), heavily corniced on

the northeast where it falls off to the lower head-basin of the icefield.

On July 16th, we left the high camp at a quarter of four—at least we

think so, although our clock had been set by the average of three

guesses and did not agree with the rising sun! Crossing the lower ice,

our way lay through the crev-assed draw just west of the conspicuous

moraine and rock-ridge swinging down from Gilgit. Reaching the upper

basin, which is uncrevassed and sloping just enough to make a fine

ski-ground, we crossed to the base of Nanga Parbat, working across a

little schrund and up the shaly northwestern buttress, which from camp

looked like an enormous black gendarme. Here there was a bit of

climbing. I was the middle man on the rope and Palmer last—Edward having

jokingly remarked that he wanted a good anchor on the end, in case he

should unexpectedly plumb the depths of a crevasse—and for a short

stretch my view was entirely obstructed by our guide’s boot-soles,

scratching their way upward.

The morning mist was

rising; everything became hidden except the foreground, but we were soon

on the crest and followed a steepening snow-ridge to the summit. Clouds

continued to blow in, so after a short rest we descended to a warmer

corner, along the southeastern rocks, where slopes on the west allowed

us to cut down to the bergschrund. This we jumped—the slope was steep,

and our form most execrable—and skirted the base of the mountain to our

old track on its northern side. Keeping high on the slopes, we crossed

to Gilgit, and ascending from the west were on top a few minutes after

noon.

The weather, which had

been smoky, cleared suddenly. The icefield below us in unbroken

whiteness is the southerly terminal source of the North Saskatchewan.

That tiny green island at the ice margin is our meadow camp—absurdly far

below, as if on a different planet. Howse River is seen on its northern

course. Mount Forbes (11,902 feet), the fifth elevation of the Canadian

Rockies, towers across the valley; a grim, snow-powdered spire it is,

worthy of comparison to the Matterhorn or the Dent Blanche, although

from few points can these Swiss peaks equal their Canadian rival in

sheerness of line. Beyond, in the north, distant peaks are visible—Lyell

and Columbia—with bits of icefield that seem like great white birds

soaring afar. To the south and west, one gazes across glaciers and

towers from which descend streams to the Bush and Columbia Valleys; and

across the ranges to peaks of the Selkirks, rising dimly in the haze.

The southeast ridge of Nanga Parbat curves brokenly and rises in dizzy

heights to the spires and pinnacles of Mount Mummery, whose black

precipices wall the head of Waitabit14 Valley.

But it was always the

icefield itself that held our attention; we were never tired of admiring

the prospect, perhaps because its contrasts made it one of the most

picturesque landscapes we had ever seen. The vast field of ice, at its

terminus, is in close apposition to the dark green of fir-trees, beyond

which is a flat of gravel-islands through which runs the river, a

silvery line, into the north. Distant patches of yellow meadow cling to

the bases of dark, shattered towers; range after range is seen, in

relief intensified by sunshine and shadow; snowfields are glittering, in

light which might in a moment be cut off in the blue shadow of moving

cloud.

In just five hours from

the high camp, on July 18th, we were on top of Mount Freshfield (10,945

feet), the only summit of the group that has been climbed more than

once. The route up a broad snow-filled gully, just east of the

Freshfield-Dent icefall, leads in interesting fashion to the slopes

opposite Pilkington. Ascent was then made obliquely to the south and the

summit gained over an easy rock crest. The day was smoky and we had no

distant view; so a glissade was made homeward, camp being reached in

many minutes under three hours. Edward soon had a bowl of erbswurst soup

ready, and after lunch we struck the tent and packed our belongings down

to the Freshfield tongue.

All this time, Jim had

packed bread—and an occasional ptarmigan—up to the high camp for us.

Bill and Tommy down below had been getting restless, although they spent

part of every day on the glacier, prospecting in the moraines.

On the last day, July

20th, Edward and I made the ascent of Coronation Mountain (10,420 feet)

from the Freshfield Glacier.15 It is the imposing, massive peak named by

Collie, and is well seen from the mouth of Forbes Brook as a broad-based

rock mountain with a steep glacier on its northern face. Leaving camp at

four o’clock in the morning, we ascended the ice for more than a mile

and took to the bush on the north side of a gully sloping down between

Mount Garth and Coronation. At timber-line, steep grass slopes and loose

rocks led up to morainal debris below two small hanging glaciers; the

tongue to the north was reached without delay and the snow above

ascended, a sharp watch being necessary because of occasional stones

falling from a wall nearby. It was not altogether easy; the slopes

became steep and hard, requiring some cutting before the arete was

reached east of the pyramidal summit. Two rocky gendarmes were traversed

below the top, the sheer drop to Forbes Brook making it an exciting

performance. Mount Forbes was directly opposite, its superb ridges

looming grandly through the smoke, and we could trace out the difficult

route by which it is ascended. But we had no distant view, and a

chilling wind compelled us to beat a retreat as soon as a cairn was

built. Glissades on the steep slopes made descent rapid, and we reached

camp shortly after noon, quite ready for lunch.

Forest-fire smoke,

occasionally a drawback in Canadian mountaineering, continued, so on the

following day camp was broken. We had climbed six lovely peaks, each

exceeding 10,000 feet in elevation, and were inclined to be quite

content with our luck. But let no one think that the climbs have been

exhausted; more than half the peaks of the group remain virgin,

Freshfield being the only one of all that has been visited more than

once. Several of the unclimbed peaks —Garth (9970 feet), Pangman (10,420

feet), Helmer (10,045 feet), and Solitaire (10,800 feet), to mention

only a few—appear difficult enough to keep strenuous climbers out of

mischief for at least a week or two.

John McDonald of Garth,

fur-trader, was in charge of Fort George in 1793, and of Fort de l’lsle

on the Saskatchewan in 1805. Rocky Mountain House was built under his

direction in 1799. He crossed Howse Pass during the winter of 1811 to

bring supplies to David Thompson on the Columbia.

Peter Pangman, an

original partner of the North-West Company, ascended the Saskatchewan as

far as the location of Rocky Mountain House in 1789.

Nowhere in the Rockies

can one reach such a tremendous icefield with greater ease, and the

possibility of establishing a high camp will ever be an advantage when

the more distant peaks are to be gained. There are problems for the

student of glaciology; and, in this area, many are the unanswered

riddles. The scenic magnificence of the upper basin is beyond all words:

no description does justice to sunsets, such as we saw night after night

from the soft heather-carpet of the upper meadow, turning the icefield

into a bowl of colours that would have puzzled an artist.

You should go there

yourself to understand. Perhaps you will see the range as we did, one

day when a layer of mist and fog hid all the mountains and left only the

icefield and the lower cliffs visible in sombre hue. The sun broke

through; a little breeze came up; there was a lowering of the

mist-level; the snowy peaks appeared above in gleaming iridescence. The

illusion could not have been bettered—it was as if another Universe were

floating in space, close above our own. |