|

Growth of trade —

Official returns — Great Britain— Canada—United States—France and

Germany—Imports and exports—Attractions for settlers—Capital brought

into the Dominion—Increased cost of living — Government inquiry — Causes

of the increase—Plain living and high thinking— Emigration Amendment

Bill—Protests and criticisms—Lord Crewe’s protest—Modifications of the

Bill—Tariff and Reciprocity—Petition to the Government—The statement of

the case by experts—Sir Wilfred Laurier’s reply — A counterblast— The

general election.

THE growth of trade in

Canada has made vast strides, each decade showing a substantial increase

on the previous one, and nearly doubling between 1900 and 1910. Taking

the year 1870 as a basis, the march of prosperity is shown in the

following official returns:

1870 ............total

trade £29,677,565

1880 ............„ „ £34,880,241

1890 ............„ „ £43,721,478

I900 ............» » £76,303.447

1910 ............» ». £138,642,244

An analysis of the

trade operations shows that the largest was transacted with the United

States, being 49.70 per cent. Great Britain comes next with 36.16 per

cent., the remainder is scattered over 70 countries. France comes third,

her imports, consisting of grains, tinned fish, fruits, pulp and

agricultural implements. Germany takes the fourth place with grain,

tinned fish and fruit.

Making a further

comparison during the past ten years, Canada has outstripped the United

States and Great Britain, the figures being, Canada, 1899-1909 increase,

88.14 Per cent.; United States, 55.19 per cent. ; Great Britain, 37.81

per cent.

The rapidly increasing

population of the Dominion, which has naturally stimulated trade,

accounts for Canada’s lead. The fact is an illuminating one, that, with

the exception of the Argentine, the Dominion holds the premier place for

trade increase in the world during the last decade.

Taking the trade per

head the figures work out differently. Great Britain comes out top in

1909 with an increase per head in round numbers of £21, Canada, £18,

United States, £7.

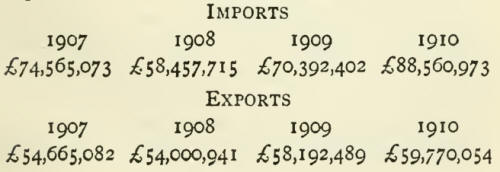

During the past four

years, 1907-1910, the official returns show the up-grade of Canada’s

import and export trade:

The attractions of the

Dominion for the young and enterprising of all nations have annually

swelled the number of settlers. To this circumstance much of the rapid

strides she has made must be attributed. Settlers have not come

empty-handed. Many of them possessed sufficient capital to start

advantageously; and, coupled with industry, the success of that class of

emigrant was practically assured.

Official statistics

show how widespread the influx has been. From 1897 to 1910, British

settlers amounted to 600,411, European continent, 445,766, United

States, 529,268.

Of capital and money

effects it is estimated that in five years, 1905-1910, over £65,000,000

have been brought into Canada.

With the rapid growth

of population and industries, the cost of living has greatly increased.

Whilst this may be taken as symptomatic of the march of wealth, the rate

of the rise in commodities has assumed such a high figure that the

matter has been made the subject of official inquiry, and a report has

been issued from the Government Labour Department of the Dominion.

In the year ending

1909, the cost of grain and fodder rose 49.9 per cent.; cattle, sheep

and fowls, 48.6 per cent.; dairy produce, 33 per cent.; wholesale price

of leather, boots and shoes, 35 per cent.

Agricultural products,

both raw material and manufactured articles, show the greatest advance.

On the other hand,

imported goods are lower than they were during 1890-1899. Mine products

have only slightly increased, and if coal be excluded they are below the

average. Sugar was only half the price it commanded in 1895, and tea was

reduced from 2s. 6d. to 3s. 9d. per lb. to from 1s. 0½d. to 1s. 8d. per

lb.

These reductions have

been regarded as an inadequate set-off against the inflated value of

more important commodities. Bread has increased 46 per cent., wheat 75

per cent., and flour 60 per cent., house rental 25 to 30 per cent.,

clothing 25 per cent. Wages have advanced meanwhile, but not in

sufficient proportion to balance the more costly housekeeping account.

The matter has been

ventilated in the Press during the current year, and the acuteness of

the discussion has been indicated in such pointed questions as the

following: Why is meat double the price of twenty-five years ago? Why

are eggs 300 per cent, higher? Why is good butter a luxury for the few?

Why are other necessaries so inflated in price ? Can anything be done to

check the upward tendency? Are there not unnatural causes at work which

are responsible for these conditions? Does the law of supply and demand

sufficiently explain the phenomenal increase in the cost of living?

The answers of experts

and Government officials vary, but on the whole give a fair statement of

the case. Increase in prosperity is the root factor that operates in

increased cost. As one writer states, the trouble lay “not in the high

cost of living, but in the cost of high living.” The higher standard of

life set up by the wealthy section of the community, by no means a

negligible one in Canada, has diverted labour from the production of

necessaries to that of luxuries, such as motor-cars, yachts, costly

dress fabrics and luxurious commodities generally. The class which

demands the best of everything, and will have it at all cost, has been a

growing one throughout the Dominion. Mr. C. C. James, Deputy Minister of

Agriculture for Ontario, regards this factor as such an active one in

the higher prices of products, that he prescribes “plain living and high

thinking” as the remedy. The rural population of Ontario had decreased,

from 1,108,874 in 1899 to 1,047,016 in 1909, whilst in the same period

the population of cities and towns had grown from 901,874 to 1,197,274.

The effect on the production of the necessaries of life produced by

these changes is obvious.

Local combines are

another active cause in the greater cost of living. This can scarcely be

eliminated, inasmuch as Canadian exports can be purchased in some cases

at a lower rate in Liverpool than in Toronto, and agricultural

implements made on the shores of Lake Erie command a higher figure in

Calgary than in London. United States trusts in meat and kindred

commodities also affect Canadian prices.

Economic changes in the

West through emigration have a direct bearing on the question. The rapid

growth of New Canada has diverted trade in cattle to speculation in

land. Huge ranches have been cleared in the interest of the incoming

settlers. The scarcity of livestock in the United States has driven

dealers to the Dominion market. They pay high prices, and the Canadian

wholesale merchants are compelled to do likewise in order to hold their

own with their neighbouring competitors. Some one has to pay back, and

it naturally falls to the lot of the consumer. Mr. Mackenzie King,

Minister of Labour, summarizes the causes of increased cost of living in

Canada as follows :—

“1. Extravagance of the

rich. 2. High standard of living among the masses of the people. 3.

Increase in population, largely through emigration. 4. Increase in the

supply of gold. 5. Large expenditure in public works. 6. Higher wages.”

The economic law of

supply and demand lies at the root of the whole question. Canada’s

increase of population has not been balanced by an equal increase in

marketable commodities, either in kind or in skill. Labour is dear

because labour is scarce. Where there is competition in supply prices

right themselves. I was struck with this in connexion with the

restaurant industry. The system of boarding out largely prevails in

Canada, not only for luncheon but for all meals, breakfast included.

Apartments are let with practically no attendance, and even hotels quote

separate terms for rooms and board. Many of the Vancouver restaurants

never close day or night all the year round, and in the leading streets

are extremely numerous. But the supply is equal to the demand, possibly

exceeds it, with the result that although provisions are dear, dinners

are cheap, and eighteen-pence will procure quite as good a luncheon in

Winnipeg or Vancouver as in the Strand or Cheapside.

Despite the loud

complaints against increased cost, poverty has not so far showed its

hungry teeth in the Dominion, and the “ workhouse ”—that pathetic symbol

of civic decadence—has not yet made its appearance amongst its municipal

institutions. The amended law in regard to emigration which has been

recently introduced, has evoked protests from many quarters, as imposing

undue restrictions. The proposals, which became law May 4th, 1910, are

to the following effect:—

1. That each adult

should be possessed of £5 in addition to a railway ticket, or a sum of

money sufficient to reach a specified destination in Canada.

2. That the head of a

family should have £5 for each member of 18 years and over, and £2 for

each member between 5 years and 18.

3. That between

November 1st and end of February each year, these sums should be

doubled.

4. Exceptions might be

permitted in case of males already hired, and going to employment on

farms, females to domestic service, or persons about to join relatives.

5. The regulations did

not apply to Asiatics, who were required to possess £40 each, except in

the case of emigrants from countries with which Canada might have

special treaties.

These provisions caused

considerable discussion in the Dominion Parliament. The reason for them

was stated by the Minister of the Interior on January 19th as follows:—

“When the Act of 1906

was introduced it was framed with a view of dealing with emigrants from

over seas. Although it applied to emigrants from across the line, it was

especially framed to meet the other conditions. Now it has become

necessary to make similar provisions for the exclusion of undesirables

along the 3000 miles of frontier between Canada and the United States,

that we formerly had carried out at the ocean ports. And as the Act was

drawn with a view to applying at the ocean ports, it is necessary that

it should be amended in its definitions and operations so as to clearly

and definitely provide for the exclusion of undesirables who arrive in

Canada by rail or by road. There has also arisen since the passage of

the Act of 1906, the question of Asiatic emigration. And while in that

respect the Act does not require much change, still it has been thought

desirable to provide for effectively dealing with that class of

emigration, not so much by the introduction of a new principle, but to

provide a specific means for the enforcement of that principle. This

Bill also provides for relieving the situation as it at present exists,

in which the Government has to exercise an arbitrary authority in the

exclusion of emigrants. This Bill provides that under certain

circumstances a Board of Inquiry shall sit and decide on the merits of

the cases brought before it, a record of each case being kept.”

Protests were made

against the regulations by British emigration and charitable

organizations generally. A statement was contributed to “The Standard”

by Lord Strathcona, which sought to soften the asperity of the

restrictions by the assurance that they were only directed against an

unsuitable class, upon whom it was desirable that a check should be

imposed.

The Canadian

Manufacturers' Association opposed the Bill as seriously restricting the

importation of artisans. A portion of the Canadian Press joined in the

outcry, indicating the shortage of labour in manufacture as a strong

reason against the barring of artisan labour, which was as essential as

farmers to the well-being of the country.

The regulations

received support from other quarters, but a protest from Lord Crewe had

considerable weight, and led to some modification in the Bill. Of the

terms contained in this memorial from the Colonial Secretary particulars

were not published. As the outcome, the Canadian representatives in

great Britain were intrusted with large discretionary power in dealing

with emigrants other than the farming class, who had the prospect of

work on landing in the Dominion.

The question of tariffs

has become a burning one in Canada. In December 1910 a deputation of

over 1000 western farmers waited on the Dominion Government at Ottawa. A

considerable number of the farming class from Ontario, Quebec and the

maritime provinces joined the delegation. Indirectly the deputation was

the outcome of organized associations, banded together in pursuit of

common agricultural interests. Directly, the speeches of Sir Wilfred

Laurier, during his western tour and pending reciprocal relations with

the United States, led the farmers to definitely formulate their

demands. These were embodied in a series of resolutions endorsed by the

National Council of Agriculture of which the following is an epitome :—

1. Urging the

Government to acquire and operate public utilities under an independent

commission.

2. To erect the

necessary works, and establish a modern and up-to-date method of

exporting meat.

3. To obtain ownership

and public control of the Hudson Bay Railway.

4. To amend the Railway

Act in certain particulars.

5. Urging Reciprocity

with the United States, and the reduction of duties on British goods.

Papers were read on

these subjects, but the discussion most vital and interesting followed

on the question of Reciprocity and duties.

Tariff was described by

Mr. J. W. Scallion, President of the Manitoba Grain Growers, as “a great

burden upon the agricultural industry and the great body of consumers.”

The delegates

representing the agricultural interests of Canada, and the mass of the

common people, “strongly protest against the further continuance of a

tariff which taxes them for the special benefit of private interests.

They say that this is wrong in principle, unjust and oppressive in its

operation and nothing short of a system of legalized robbery. Prices for

the produce of the farm are fixed in the markets of the world by supply

and demand and free competition when these products are exported, and

the export price fixes the price for home consumption ; while the

supplies for the farm are purchased in a restricted market, where prices

are fixed by combinations or manufacturers and other business interests

operating under the shelter of our protective tariff.”

The speaker was in

favour of reciprocal relations with the United States, but more than

Reciprocity was needed.

“We are in favour,” he

said, “of an increase to 50 per cent, in the British Preference, and in

favour of further increase from time to time until the duty on British

interests is entirely abolished.”

Mr. E. C. Drury,

Secretary of the National Council of Agriculture, advanced as an

argument in favour of fiscal changes, the decline in agricultural

interests—the farming community had decreased in every Canadian Province

east of Manitoba, and that Protection was no longer needed to encourage

infant industry. He advocated British Preference, and ultimate Free

Trade with England.

An argument on the

effect of taxation upon agricultural implements was advanced by Mr. R.

Mackenzie of the “Grain Growers’ Guide.” Agricultural implements

manufactured in Canada, according to the last census, amounted to

£2,567,149. Of that amount £468,565 worth was exported. The imports that

year amounted to £318,962. “It is now conceded,” said Mr. Mackenzie,

“that the manufacturer adds to the selling price of his commodity the

total amount of the protection granted him by the customs duty. The

farmers of Canada thus paid to the Government that year £63,736, and to

the manufacturers of farming implements £419,676.

A similar case was

urged against taxation of woollens, cottons, leather, cement, and

cutlery, which paid to the Government £197,831, and to the manufacturer

£2,455,429.

In 1905 upon the sales

of Canadian manufactures amounting to £141,200,000 a tribute was

collected from the consumers of £38,000,000.

The demands on fiscal

changes were formulated as follows:—

1. “That we strongly

favour reciprocal free trade between Canada and the United States in all

horticultural, fuel, agricultural, and animal products, spraying

materials, fertilizers, illuminating and lubricating oils, cement, fish,

and lumber.

2. “Reciprocal trade

between the two countries in all agricultural implements, machinery,

vehicles . . . and in the event of a favourable arrangement being

reached it be carried into effect through the independent action of the

respective governments, rather than by the hard-and-fast requirements of

a treaty.

3. “We also favour the

principle of the British Preferential Tariff, and urge an immediate

lowering of the duties on all British goods to one half the rates

charged, . . . and that any trade advantages given to the United States

in reciprocal trade relations be extended to Great Britain.

4. “For such further

gradual reduction of the Preferential Tariff as will ensure the

establishment of complete free trade between Canada and the Motherland

within ten years.

5. “That the farmers of

this country are willing to face direct taxation in such form as may be

advisable to make up the revenue required under new tariff conditions.”

Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s

reply was guarded. He expressed surprise that Eastern farmers should

have joined Western in the petition. With the principle of some of the

demands he was in sympathy, but with the question of the nationalization

of railways and public utilities he kept an open mind.

With regard to

Reciprocity the Government wanted better commercial relations with the

United States, but “any change in trade relations” with regard to

manufactured products was a more difficult matter, and “Nothing we do,”

he stated, “shall in any way impair or affect the British Preference;

that remains a cardinal feature of our policy.”

The Toronto “Globe,”

the Liberal organ, regarded the movement set afoot as destined to affect

the entire fiscal question. The growth of the West was so rapid that in

a dozen years it would be in a position to dictate the fiscal policy of

the Dominion, and to ignore it would be folly.

The St. John’s

“Standard,” a Conservative journal, sought to discount the value of the

memorial by stating that the arguments were stale and nothing more than

a repetition of those used by Sir Richard Cartwright and the Liberals in

the eighties.

Other criticisms were

to the effect that the deputation only represented 25 per cent, of the

Western farmers; that the proposals meant diverting the trade of Great

Britain to the States, and that the entire movement was of a class

character. As might be expected, a counterblast came from the Canadian

Manufacturers’ Association, which charged the Western farmers with

ignoring every one but themselves; that Canada had become united and

strong under moderate protection, and the movement was controlled in the

main by “New Canadians,” unacquainted with the history or the aims of

the Dominion.

Mr. T. A. Russell, of

the Toronto Cycle and Motor Co., pointed out that Canada had been

unfairly treated by the United States.

“For the past ten

years,” he said, “our purchases from the United States were

£320,000,000. Their purchases from us were £160,000,000. They are twelve

times greater in population. In other words, our purchases from the

United States were £6 per head, theirs from us 4s. 6d. per head. The

United States average tariff on all goods, dutiable and free, is 24 per

cent., ours 16 per cent. Theirs on dutiable goods, 42 per cent., ours 27

per cent.” He urged that Canada’s natural resources would be wasted

instead of conserved, and that its seaports would be sacrificed to those

of New York and Boston. Indirect taxation affected farmers less than

other classes, whilst direct taxation would be correspondingly heavy,

and all this in view of the fact that farmers were doing well.

“Our Western country is

being filled up as fast as we can assimilate the additions. Railways are

being constructed, our factories are busy, our country’s credit never

stood so high. And what of the farmer? In the West he has grown rich in

a decade; in the Niagara Peninsula his land values have increased

tenfold ; throughout Canada he gets 50 per cent, more for his grain and

fodder than he did a decade ago, 48 per cent, more for his meat and 35

per cent, more for his dairy produce, and this at a time when the cost

of manufactured goods has, as a whole, remained stationary or

decreased.”

Before the above

particulars had gone into type the result of the Canadian elections came

to hand. The Liberals fought the battle on the question of Reciprocal

Relations with the United States, and they lost, and lost heavily. Thus

the long tenure of Government under Sir Wilfrid Laurier comes to an end,

and determined by an issue on which he confidently expected to secure a

following that would reinstate him in power. How far the result was

determined by the fiscal question per se, or the larger issue of a

fiscal alliance with the United States which might become the thin end

of the wedge to a Republican alliance, are matters that are open to

debate.

Of one thing I was

deeply impressed during my travels, namely, the intense loyalty of all

classes to the British Crown, and if, as is surmised by many, the

election was determined by an ultimate question of “Under which Flag?”

the result will be by no means a surprise to any one who understands the

passionate allegiance of the Dominion to the Mother Country. |