|

Shakespeare's play of "As You Like It" is

an eulogy of the flight from the highly formal life of city life to the

simplicity of the forest and the retirement of the plains. Even in the

banished Duke, there is a strain of oddity and quaintness. Not many

years after the middle of last century, a Detroit lawyer fled from the

troubles of society and city life to the peaceful plains of secluded

Assiniboia. Marrying, after his arrival, a daughter of one of our best

native families, and on her death, a pure Indian woman, he reared a

large family. The poetic spirit of Frank Larned was never repressed, and

we give, with some changes, to suit our purpose, and at times some

divergence from the views expressed, scenes of the Red River Settlement,

in which he, for more than a generation, dwelt.

BRITAIN'S ONE UTOPIA—SELKIRKIA

That brave old Englishman, Thomas

More—afterwards, unhappily for his head—Lord High Chancellor of

England—wrote out, in fair Latin,—in

his chambers in the City of London, over three centuries ago—his idea of

an Utopia. This, modest as are its requirements, has yet found no

practical illustration, even among the many seats of the great

colonizing race of mankind.

The primitive history of all the colonies

that faced the Atlantic—when the new-found continent first felt the

abiding foot of the stranger—from Oglethorpe to Acadia, reveals, alas!

no Utopia. It remained for a later time,—the earlier half of the present

century, amid some severity of climate, and under conditions without

precedent, and incapable of repetition,—to evolve a community in the

heart of the continent, shut away from intercourse with civilized

mankind—that slowly crystalized into a form beyond the ideal of the

dreamers—a community, in the past, known but slightly to the outer world

as the Red River Settlement, which is but the bygone name for the one

Utopia of Britain—the clear-cut impress of an exceptional people living

under conditions of excellence unthought of by themselves until they had

passed away.

A people, whose name in the vast

domain, was in days by gone, sought out and coveted by all. Unknown

races had rested here and gone away, leaving

only their careful graves behind them. The "Mandans"—the brave, the

fair, the beautiful, and the "Cheyennes," pressed by the "Nay-he-owuk,"

and the "Assin-a-pau-tuk," had quitted their earthen forts on the banks

of the streams and urged their way to the broader tide of the Missouri.

More fatal to the conquerors came afterward, the white man, "Nemesis" of

all Indian life, spying with the instinct of his race, a spot of

abounding fertility, where the great water-reaches stretched from the

mountains to the sea, and southward touched almost the beginning of the

great River of the Gulf.

Quick changing his errant camp for

barter into a stronghold for the trade, making the "Niste-y-ak" of the "Crees"

his settled home, the white man's grasp of the fair domain but grew with

years. From the seas of the far north came with the men, fair-haired,

blue-eyed women and children. The glamour of the spot, the teeming soil,

the great and lesser game, that swam past,—or wandered by their

doors—soon drew to this Mecca of the Plains and Waters—the roving,

scattered children of the trade—Bourgeois and voyageur alike heading

their lithe and dusky broods. Here touched and fused all habitudes of

life, the blended races, knit by ties conserving every divergence of

pursuit, all forms of faith and thought, free from assail or taint

begotten of contact with aught other

than themselves. A people whose unchecked primal freedom was afterward

strengthened by the light hand of laws that conserved what they most

desired; whose personal relations with their rulers were of such

primitive character as to make the Government in every sense paternal;

the petty tax on imports attending its administration one practically

unfelt!

A people whose land was dotted with

schools and churches, to whose maintenance their contributions were so

slight as to be unworthy of mention. The three separate religious

denominations, holding widely different tenets—elsewhere the cause of

bitter sectarian feeling,—was with them so unthought of as to give where

all topics were eagerly sought—no room for even fireside discussion.

Side by side, "upon the voyage,"—as they termed their lake or inland

trips—the Catholic and the Protestant knelt and offered up their

devotions—following the ways of their fathers,—no more to be made a

subject of dispute than a difference in color or height.

The cursings and obscenities that

taint the air and brutalize life elsewhere, were in this quaint old

settlement unknown. Sweet thought, pure speech, went hand in hand, clad

in nervous, pithy old English, or a "patois" of the French, mellowed and

enlarged by their constant use of the

liquid Indian tongues, flowing like soft-sounding waters about them,

their daily talk came ever welcome to the ear.

Where locks for doors were unknown, or,

known, unused, where a man's word, even in the transfer of land, was

held as his bond—honesty became a necessity. Lawyers were none. Law was

held to be a danger. Still the importance attached by simple minds to an

appearance in public, the amusing belief cherished by some, that, if

permitted to plead his own case, exert his unsuspected powers, there

could be but one result, brought some honest souls to the Red River

forum, with matter of much moment, "the like never heard before." None

can read the quaint, minutely-detailed record of these "causes celébres"

that shook the little households as with a great wind, without a smile,

or resist the conviction that no scheme of an English Utopia can safely

be pronounced perfect without some such modest tribunal to afford vent

for that ever-germinating desire for battle inherent in the race.

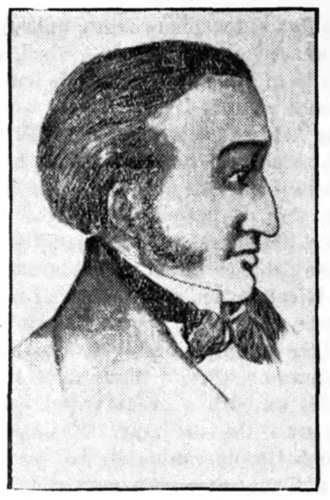

ALEXANDER ROSS

Sheriff and Author.

Came to Red River Settlement in 1825 from British Columbia. Died in

1856.

Their manners were natural, cordial,

and full of a lightsome heartness that robed accost with sunshine,—a

quietude withal—that rare quality —that irked them not at all—one

gathered from their Indian kin-folk. Their knowledge of each other

was simply universal—their kin ties almost as general. These ties were

brightened and friendships reknit in the holiday season of the year, the

leisure of the long winters, when the far-scattered hewn log

houses—small to the eye—were ever found large enough to hold the welcome

arrivals,—greeted with a kiss that said, "I

am of your blood." These widespread affiliations broke down aught like

"caste." Wealth or official position were practically unheeded by a

people in no fear of want and unaccustomed to luxuries, who sought their

kinswoman and her brood for themselves, not for what they had in store.

The children and grandchildren of men, however assured in fortune or

position, wove anew equalizing ties, seeking out their mates as they

came to hand; hence a genial, not a downward level, putting to shame

fine-spun theories of democracy in other lands—spun, not worn.

This satisfaction of station—as

said—grew out of the slight exertion necessary for all the wants of

life, with unlimited choice of the finest land on the continent; the

waters alive with fish and aquatic fowl; rabbits and prairie fowl at

times by actual cart-load; elk not far, and countless buffalo

behind,—furnishing meat, bedding, clothing and shoes to any who could

muster a cart or go in search; the woods and plains in season, ripe with

delicious wild fruit, for present use or dried for winter,—the whole

backed by abundant breadstuffs. The quota of the farmers along the

rivers, whose fertile banks were dotted by windmills, whose great arms

stayed the inconstant winds, and yoked the fickle couriers to the great

car of general plenty.

Poverty in one sense certainly existed;

age and improvidence are always with us, but it was not obtrusive, made

apparent only towards the close of the long winter, when some old

veteran of the canoe or saddle would make a "grand promenade" through

the Settlement, with his ox and sled, making known his wants,

incidentally, at his different camps among his old friends, finding

always before he left his sled made the heavier by the women's hands.

This was simply done; few in the wild country but had met with sudden

exigencies in supply, knew well the need at times of one man to another,

and, when asked for aid, gave willingly. Or it may be that some

large-hearted, jovial son of the chase had overrated his winter store,

or underrated the assiduity of his friends. His recourse in such case

being the more carefully estimated stock of some neighbor, who could in

no wise suffer the reproach to lie at his door, that he had turned his

back, in such emergence, upon his good-natured, if injudicious

countryman.

This practical communism—borrowed

from the Indians, among whom it was inviolable—was, in the matter of

hospitality, the rule of all, —a reciprocation of good offices, in the

absence of all houses of public entertainment, becoming a

social necessity. The manner of its exercise hearty, a knitting of the

people together,—no one was at a loss for a winter camp when travelling.

Every house he saw was his own, the bustling wife, with welcome in her

eyes, eager to assure your comfort. The supper being laid and dealt

sturdily with, the good man's pipe and your own alight and breathing

satisfaction, —a neighbor soul drops in to swell the gale of talk, that

rocks you at last into a restful sleep. How now, my masters! Smacks not

this of Arcady?

Early and universal marriage was the rule.

Here you received the blessings of home in the married life, and the

care of offspring. There were thus no defrauded women—called, by a cruel

irony, "old maids"; no isolated, mistaken men, cheated out of

themselves, and robbed of the best training possible for man. This vital

fact was fraught with every good.

On the young birds leaving the

parent nest, they only exchanged it for one near at hand—land for the

taking; a house to be built, a wife to be got—a share of the stock, some

tools and simple furniture, and the outfit was complete. The youngest

son remained at home to care for the old father and mother, and to him

came the homestead when they were laid away. The conditions were all

faithful, home life dear indeed.

To the Hunters accepting their fall in the

chase no wilder thought could scarce be broached than that of solicitude

as to the future of their young. Boys who sat a horse almost as soon as

they could walk, whose earliest plaything was a bow and arrows; girls as

apt in other ways, happy; sustained in their environment with a faith

truly simple and reverent.

With so large an infusion of Norse blood

and certain traditions anent "usquebae" and "barley bree" it would—with

so large a liberty—be naturally expected, a liberal proportion of

drouthy souls, but with an abundance of what cheers and distinctly

inebriates in their midst they were a temperate people in its best

sense, with no tippling houses to daily tempt them astray their supplies

of spirits were nearly always for festive occasions. "Regales" after a

voyage or weddings that lasted for days, and these at times under such

guard as may be imagined from the presence of a custodian of the bottle,

who exercised with what skill he might his certainly arduous task of

determining instantly when hilarity grew into excess.

This novel feature applies, however,

almost entirely to the English-speaking part of the people. The Gallic

and Indian blood of the Hunters disdained such poor toying with a single

cherry and drank and danced and drank and danced again with an abandon,

an ardor and full

surrender to the hour characteristic alike of the strength of the heads,

the lightness of their heels and the contempt of any restraint whatever.

These were, however, but the occasional

and generous symposiums of health and vigor that rejects of itself

continued indulgence. Our Utopia would be cold and pallid indeed lacking

such expression of redundant strength, and joyful vigor.

Certainly the greatest negative blessing

that this exceptional people enjoyed, was that they had no politics, no

vote. The imagination of the average "party man" sinks to conceive a

thing like to this; yet, if an astounding fact to others, no more

gracious one can be conceived for them selves. In the unbroken peace in

which they lived politics would be but throwing the apple of discord in

their midst, an innoculation of disease that they might in the delirium

that marked its progress vehemently discuss remedies to allay it.

Another great negative advantage was

the peculiar and admirable intelligence of the great body of the

population. The small circulating collection of books in their midst

attracting little or no attention, their own limited to a Bible or

prayer book,—many not these. With their minds in this normal healthy

state, unharassed by the sordid assail of care, undepressed by any sense

whatever of inferiority, unfrayed by the trituration of the average

book, their powers of apprehension—singularly clear—had full scope to

appropriate and resolve the world about them, which they did to such

purpose as to master every exigence of their lives. Seizing upon the

minutest detail affecting them they mastered as if by intuition all

difficult handiwork, making with but few tools every thing they required

from a windmill to a horseshoe.

Their real education was in scenes of

travel or adventure in the great unbroken regions sought out by the fur

trade, their retentive memories reproducing by the winter fireside or

summer camp pictures so graphic as to commend themselves to every ear.

The tender heart and true of the brave old

knight, Sir Thomas More, put a ban upon hunting in his Utopia. Alas and

alack for the wayward proclivities of our Utopians, predaceous creatures

all, hunting was to them as the breath of their nostrils, for to them,

unlike the sons of Adam, it was given—with their brothers resting upon

the tranquil river—to lay upon the altar of their homes alike the fruits

of the earth and the spoils of the chase.

What pen can paint the life of the

"Chasseurs of the Great Plains," tell of the gathering of

the mighty Halfbreed clan going forth—each spring and fall—in a tumult

of carts and horsemen to their boundless preserves, the home of the

buffaloes, whose outrangers were the grizzly bear, the branching elk,

the flying antelope that skirted the great columns, the last relieving

the heavy rolling gait of the herds by a speed and airy flight that

mocked the eye to follow them, scouting the dull trot of the prowling

wolves—attent upon the motions of their best purveyor—man.

What a going forth was theirs! this array

of Hunters, with their wives and little ones; this new tribe clad in

semi-savage garniture, streaming across the plains with cries of glee

and joyance; the riders in their "travoie" of arms and horse

equipment—the vast "brigade" of carts and bands of following horses,

kept to the cavalcade by those reckless jubilants—the boys—seeming a

part of the creatures they bestrode. The sunshine and the flying fleecy

clouds, emulous in motion with the troop below: what life was in it all;

what freedom and what breadth!

And as the sun sank apace and the

guides and Headmen rode apart on some o'er-looking height and reined

their cattle in, the closing up of the flying squadron for the evening

camp, the great circular camp of these our Scythians proof against

sudden raid crowning the landscape

far and wide, seen, yet seeing every foe, whose subtle coming through

the short-lived night was watched by eyes as keen as were their own.

When reached, their bellowing, countless

quarry: the plain alive and trembling with their tumult, what tournament

of mail-clad knights but was as a stilted play to this rude shock of man

and beast—carrying in a cloud of dust that hid alike the chaser and the

chased, till done their work the frightened herds swept onward and away,

leaving the sward flecked with the huge forms that made the hunters'

wealth! And now! on: fall prosaic from the wild charge, the danger of

the fierce melee!—drifting from the camp the carts appear piled red in a

trice with bosses, tongues, back fat and juicy haunch, a feast unknown

to hapless kings.

We but glance at this great feature, that

fed so fat our Utopia, leaving to imagination the return, the trade, the

feasting and the fiddle when lusty legs embossed by "quills" or beads

kept up the dance.

The outcome of the "Plain Hunt" was

not only a wide spread plenty among the Hunters on reaching the quiet

farmer folk upon the rivers, but also the diffusion of a sunshine, a

tone of generous serenity that sat well on the chivalry of the chase—the

bold riders of the Plain.

Beneficent nature nowhere makes her

compensations more gratefully felt than in the summer season of our

Utopia of the north, where the purest and most vivifying of atmospheres

hues with a wealth of sunshine the great reaching spaces of verdure

covered with flowers in a profusion rivaling their exquisite beauty.

Green waving copses dot the level sward, and rob the sky line of its

sea-like sweep. The winding rivers, signalled by their wooded banks,

upon which rest the comfortable homes of the dwellers in the "hidden

land" guarding their little fields close by where the ranked grain

standing awaits the sickle, turning from green to gold and so unhurried

resting. The shining cattle couched outside in ruminant content or

cropping lazily the succulent feast spread wide before them; the horses

wary of approach, just seen in compact bands upon the verge; the

patriarchal windmills—at wide spaces—signalling to each other their

peaceful task; the little groups of horsemen coming adown the winding

road, or stopping to greet some good wife and her gossip—going abroad in

a high-railed cart in quest of trade, or friendly call. And as the day

wanes, the sleek cows, with considered careful walk and placid mien,

wend their way homeward, bearing their heavy udders to the house-mother,

who, pail in hand awaiting their approach, pauses for a moment to mark

the feathered boaster at her feet, as he makes his parting vaunt of a

day well spent and summons "Partlet" to her vesper perch hard by.

O'er all the scene there rests a brooding

peace, bespeaking tranquil lives, repose trimmed with the hush of night,

and effort healthful and cool as the freshening airs of morn.

Longfellow—moving all hearts to pity—has

painted in "Evangeline" the enforced dispersion of the French in

"Acadia." Who shall tell the homesick pain, the vain regrets, the

looking back of those who peopled our "Acadia"? No voice bids them away;

they melt before the fervor of the time; hasten lest they be 'whelmed by

the great wave of life now rolling towards them. Vain retreat, the

waters are out and may not be stayed. It is fate! it is right, but the

travail is sore, the face of the mother is wet with tears.

This outline sketch proposed is at an end;

we have striven to be faithful to the true lines. There is no obligation

to perpetuate unworthy "minutæ." Joy is immortal! sorrow dies! the petty

features are absorbed in the broad ones; those capable only of conveying

truth.

The Red River Settlement in the days

adverted

to is an idyl simple and pure: a nomadic pastoral, inwrought with Indian

traits and color; our one acted poem in the great national prosaic life.

When the vast country in the far future is teeming with wealth and

luxury, this light rescued and defined will shine adown the fullness of

the time with hues all its own. The story that it tells will be as a

sweet refreshment: a dream made possible, called by those who shared in

its great calm, "Britain's One Utopia—Selkirkia." |