|

The aboriginal

inhabitants of the two colonies of British Columbia and Vancouver

Island, of which I now propose to speak, may be divided into two

classes, viz. the Coast, or, as they are generaly called, the

Fish-eating Indians, and the Inland tribes. By Fish-eating Indians must

be understood those who depend almost entirely upon fish for

subsistence; for the Inland, as well as the Coast, tribes, live to a

great extent upon salmon.

The Indians of the interior are, both physically and morally, vastly

superior to the tribes of the coast. This is no doubt owing in great

part to their comparatively slight intercourse with white men, as the

northern and least known coast tribes of both the island and mainland

are much finer men than those found in the neighbourhood of the

settlements. But it is also attributable in no slight degree to the

difference of their lives, the athletic pursuits and sports of the

Indians of the interior tending much more to healthy physical

development than the life of the Coast Indian, passed, as it is, almost

entirely in his canoe, in which he sits curled up like a Turk. The upper

limbs of a Coast Indian are generally so well proportioned and

developed, that when sitting in his canoe he might be thought a

well-grown man, but upon his stepping out it is seen that his legs are

smaller than his arms. Miserable as these limbs are in size, in shape

they are still more deformed, the lower bones becoming bent to the shape

of the side of the canoe, and the feet very much turned in. With the

women this is worse than with the men, and when they try to walk they

waddle like a parrot, crossing their feet at every step. Again, the

trade in slaves, which is carried on to a great extent among all the

Coast tribes, and tends undoubtedly to demoralize them, is not practised

in the interior. Of course the prisoners which they make in their many

fierce wars with one another are enslaved, but the practice is not made

a trade of by them as by the tribes along the shore.

To begin, then, with

the Coast or Fish-eating Indians. Mr. Duncan, the missionary teacher at

Fort Simpson, of whose labours there I shall have occasion to speak, and

upon the accuracy of whose information every reliance may be placed,

estimates the Indians of the east side of Vancouver Island, of Queen

Charlotte Sound, and of the coast of British Columbia, at about 40,000

in number. Among them four distinct languages are found to exist, each

spoken by some 10,000 souls. One of these is shared by the Songhies, a

tribe collected at and around Victoria; the Cowitchen, living in the

harbour and valley of Cowitchen, about 40 miles north of Victoria; the

Nanaimo and the Kwantlum Indians, gathered about the mouth of the

Fraser.

In the second division are comprised the tribes situated between Nanaimo

and Fort Rupert, on the north of Vancouver Island, and the mainland

Indians between the same points. These are divided into several tribes,

the Nanoose, Comoux, Nimpkish, Quaw-guult, &c., on the island; and the

Squawmisht, Sechelt, Clahoose, Ucle-tab, Mama-lil-a-culla, &c., on the

coast and among the small islands off it.

Of these the Nanoose tribe inhabit the harbour and district of that

name, which lies 50 miles north of Nanaimo; the Comoux Indians being

found to extend as far as Cape Mudge. The Squawmisht, Sechelts, and

Clahoose live in Howe Sound, Jervis Inlet, nnd Desolation Sound

respectively. At and beyond Cape Mudge are found the TJcle-tehs, who

hold possession of the country on both sides of Johnstone Strait until

met 20 or 30 miles south of Fort Rupert by the Nimpkisli and Mama-lil-a-cullas.

The Quaw-guults, and two smaller tribes, live at Fort Rupert itself.

Five of the first-named tribes muster at Nanaimo for trade, and' being

all more or less at enmity with each other, frequent encounters between

them take place there. The others assemble at Rupert, at which post

there are generally as many as 2000 or 3000 Indians to be found.

Of all these Indians the Soughies at Victoria are the most debased and

demoralised. The Cowitchens are rather a fine and somewhat powerful

tribe, numbering between 3000 and 4000 souls. The Nanaimo Indians, who

at one time were just as favourably spoken of. have fallen off much

since the white settlement at that place has increased.

I have said the distinct languages spoken by the Indians are few in

number, but the dialects employed by the various tribes are so many,

that, although the inhabitants of any particular district have no great

difficulty in communicating with each other, a white man, to make

himself understood by the various tribes, would have to learn the

dialects employed by all. And when it is considered that hardly any

attempt has been made to investigate and define the principles which

regulate their use of words, and that the common roots of the words

themselves, if they possess such, are at present quite out of the

student’s reach, the difficulties of such a task may easily be

conceived. The southern tribes, as a rule, understand the Chinook

jargon, in which almost all the intercourse between Indians and whites

is at present carried on. A few men may be found in almost all of the

northern, and many of the inland Iribes, who understand it, but its use

is most common in tbe south. This Chinook is a strange jargon of French,

English, and Indian words, of which several vocabularies have been

published. It was introduced by the Hudson Bay Company for the purposes

of trading, and its French element is due to the number of French

Canadians in their employ.

The Cornoux Indians possess a very fine tract of country inside a point

called Cape Lazo, of which I shall speak hereafter. They are a large

tribe, and have the reputation of being rather savage, though we always

found them very peaceably disposed. They know quite well, however, the

value of the 6000 or 8000 acres of clear land which they possess, and

when I went over it with them, took great care to explain that the

neighbouring Indians resorted there in the summer for berries, &c., and

that a great many blankets would be required as purchase-money whenever

we wanted it, an event which they evidently contemplated.

Next to them, as I have said, come the Ucle-tahs. The most important

village of this tribe is situated at Cape Mudge, but they are spread all

over Discovery Passage and the south part of Johnstone Strait. As I have

before said, they may be regarded as the Ishmaelites of the coast, their

hand being literally against every one’s, and every one’s against them.

The Indians who come from the northward to Victoria in the summer, are

particularly guarded when passing through their neighbourhood. Several

battles have taken place at different times at or near Cape Mudge. Upon

one occasion they murdered nearly all the crew of a Hudson Bay vessel

which stopped there for water, one half-breed boy only, I believe,

escaping. They are bold as well as blood-thirsty, and by no means

disposed to yield, as Indians generally do, to the mere exhibition of

force. In the year before last some of their canoes robbed two

Chinamen’s boats off Saltspring Island, and on the ‘Forward’ being sent

after them, the villagers at Cape Mudge, which is regularly stockaded,

defied the gunboat and fired upon her. The ‘ Forward ’ had to fire shot

and shell among thorn, and to smash all their canoes, before they gave

in and surrendered the stolen goods. Had it not been for the

rifle-plates with which the crew were protected, a good many might have

been hit, as the Indians kept up a steady fire upon them for a

considerable time. I must not be understood to say that these Ucle-tahs

are the only tribe of Indians who have proved troublesome upon the

coast, but they are alone as yet in standing out after the appearance of

a man-of-war before their village. They also have a reputation, which

may not, however, be quite deserved, of being more treacherous than the

Indians of other tribes. Many stories are current of the cold-blooded

treachery of all these tribes one to the other, and sometimes to the

white men who have fallen into their hands. In 1858, for instance, some

members of the Cowitchen tribe made a most brutal and treacherous

attack.on a body of unoffending northern Indians, which I will detail,

as it illustrates, not unfavourably, the hardihood and endurance of the

red man amid the perils incidental to his life.

Information had been sent to the Governor of a canoe full of people

having been massacred in Ganges Harbour, and H.M.S. ‘Satellite' was sent

to inquire into it. Upon her arrival at Cowitchen it was ascertained

that a northern canoe with a dozen Indians in it was passing down the

inner passage to Victoria, when a white man, one of the settlers on the

north end of Saltspring Island, asked them to take him to Victoria,

calling at the settlement in Ganges Harbour on the way. They were

willing to take him to Victoria, but objected to going to Ganges Harbour

on account of the Cowitchens. The settler, however, overruled their

objections, and they finally assented to his wish. When they reached the

spot where their passenger wanted to land, they found about twenty

Cowitchens camping there. These fellows came clown to the canoe, and

made such cordial professions of friendship to the poor northerners,

that they were tempted to land. While the white man was present their

manner continued to he most friendly; but unluckily the settler’s house,

to which he wanted to go, stood some quarter of a mile back from the

shore. The moment he was out of sight the Cowitchens leaped up and fired

on the others. Those who remained in the canoe shoved off, but were

pursued and captm’ed all but one, a chief of some rank among them. Sis

of the prisoners were slaughtered with the most barbarous, wanton

cruelty; Captain Prevost of the ‘Satellite’ reporting that there were

the marks of bullets discernible all round their hearts, and that their

heads were fearfully battered in. Three women and a child were spared

and kept as prisoners, all but one of whom were eventually rescued from

them.

The Indian who escaped from the canoe swam to a small island at the

entrance of the harbour, and his subsequent struggle for life

illustrates strongly, as I have before said, the skill and endurance of

his race when reduced to extremities. Although wounded in the neck, arm,

and leg, he succeeded in floating upon a log from the island on which he

had landed to Cowitchen Harbour, a distance of 13 miles. Here he was

picked up by some other Cowitchen Indians, who, according to their own

account, let him go. At any rate he escaped, and wounded and weak as he

was, and with no other food than what roots and berries he could pick

up, made his way through the forests and the midst of his enemies to

Victoria, a distance of 45 miles, through a country entirely unknown to

him. The pleasant part of the story, however, is that, on the

‘Satellite’s’ return with the women who had been recovered from the

offending tribe, a canoe of northern chiefs, among whom was this very

man, knowing the errand she had been on, put out from Victoria to her.

Upon his going on board the first tiling lie saw was his wife, who had

been washed and dressed, and was no doubt looking better than he had

ever seen her. Although of course each thought het other had been

murdered, there was no violent manifestation of joy upon their

recognition. Captain Prevost said that her face lighted up, and she

started a little, but then stood quite still, while the man walked up to

her without any appearance of surprise or uudignified haste, kissed her

once on the forehead, aud turned away, taking no more notice of her

whatever until he was leaving the ship, when he called her to his canoe.

Kissinjr in token of affection is not an Indian habit, and must have

been taught this man, I take it, by the Koman Catholic missionaries. I

have been in their villages upon several occasions while travelling -

parties were leave-taking; and although the women, while packing up the

store of fish or venison for their husbands’ journey have cried

bitterly, and taken leave of them with every evidence of grief and

affliction, I have never seen them kiss each other.

Several instances have occurred of whites being murdered by Indians in

different parts of the colony, but I fear these murders have generally

been the result of introducing firewater, or taking liberties with the

females of the tribe; for although the Indian thinks little of selling

female slaves for the vilest purposes, he sometimes avenges an insult

offered to his own wives summarily. Their ideas, however, on this

subject are by no means clear, for they occasionally take terrible

vengeance for an insult which at another time they will not even notice.

Whenever a white man takes up his residence among them, they will always

supply him with a -wife; and if he quits the place and leaves her there,

she is not the least disgraced in the eyes of her tribe. The result of

this is, that you frequently see children quite white, and looking in

every respect like English children, at an Indian village, and a very

distressing sight it is.

Nortli of the district occupied by the Ucle-talis come the Nimpkisli,

Mama-lil-a-cula, Matelpy, and two or three other smaller tribes. The

Mama-lil-a-culas live on the mainland; the Nimpkisli have their largest

village at the month of the Nimpkish river, about 15 miles below Fort

Rupert. A picture of this place is given in Vancouver’s Voyages, and so

little has it changed in the 70 years since his visit, that we

recognised it immediately from that sketch. The Quaw-guults and other

Indians at Fort Rupert possess no peculiar characteristics, but fight

and drink when they can, after the fashion of Indians generally. I have

previously described the ‘Hecate’s’ palaver with them upon the occasion

of then having captured an Indian woman of another tribe. A palaver of

this sort is a curious sight, and some Indians are very eloquent at

them. All those present squat on crossed legs in the usual Indian

fashion. The speaker, alone standing, holds a long white pole, which he

sticks into the ground with great force every now and then by way of

emphasis, sometimes leaving it standing for a minute or so while he goes

on speaking. Then he strides to it, catches it up, and perhaps swings it

over his head, or again sticks it into the ground. The exact meaning or

purpose of this pole I do not know, but it has some particular office,

and serves, among other tilings, to ratify any agreement to which they

may come upon the subject discussed; for when they agreed finally to

give up the slave, the chief stepped forward and handed the pole to

Captain Richards.

In the third group Mr. Duncan includes all those Indians speaking the

Tsimshean language, and to whom he has devoted so much care and labour.

He divides these into four parts:—

2500 at Fort Simpson, taking the Fort as the centre. 2500 on the Naas

River, 80 or 100 miles to the northeast. 2500 on the Skeena River, 100

miles south-east. 2500 in the numerous islands in Millbanke Sound, &c.,

lying south-east of Fort Simpson.

These northern Indians, as I have before said, are finer and fiercer men

than the Indians of the south, or the tribes of the west coast of

Vancouver Island, and are dreaded more or less by them. Their foreheads,

as a rule, are not so much flattened, but then- countenances are

decidedly plainer.

It is very difficult to give anything like a correct estimate of Indian

population anywhere in the island, but upon the west or Pacific coast it

is still harder, as no attempt whatever at ascertaining their number,

even approximately, has yet been made. I imagine, however, that the

island may contain from ten to twelve thousand, of whom five thousand

live along the west coast. When speaking to Mr. Duncan once of the

difficulty of numbering the Indians, he gave a very amusing account of

the endeavour made to get a census taken at Fort Simpson. After every

means had, it was supposed, been taken to prevent them from being found

in two places at once, the operator got what was thought to be a fair

start; but nothing could induce the Indians to believe that a game of

some sort was not intended, so that as soon as the head of a house began

counting heads, the younger members of the family would dodge from one

side of the hut to the othei\ that they might be reckoned in again and

again.

The Indians of the west coast are divided into 24 tribes. Some of these

are almost extinct, while others number from 300 to 400 men. Among all

these there are but two distinct languages spoken, while the dialects

are not so numerous as on the other side.

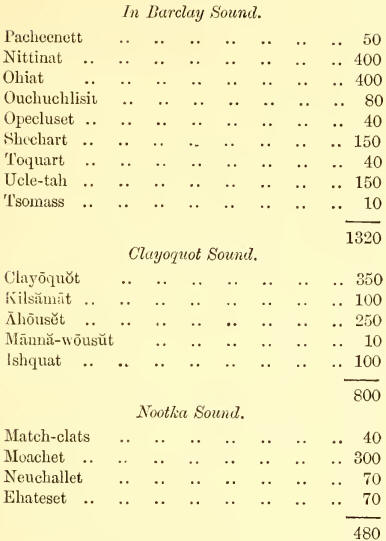

All the tribes of Barclay, Clayoquot, and Nootka Sounds speak a language

intelligible to each other. The names and approximate numbers of these

tribes are as follow:—

North of Nootka Sound

is the largest tribe of the West coast—the Kycu-cut—numbering 500 or 600

men ; and north again of these lie the Quatsino and Jvoskiemo, occupying

the two Sounds bearing those names.

East of Cape Scott, which is the north point of Vancouver Island, is a

small tribe—the Newittees, which meet the Quaw-guults at Port Rupert.

Mr. Moffatt, who was for years in charge of Fort Rupert, and had

therefore the best opportunities of judging, estimates the number of

Indians between Nootka and Newittee at 1500 men. This would make the

number of the Koskiemos, Quatsinos, and Newittees about 500.

Between Victoria and Barclay Sound are the Soke Indians, who are few in

number; while the Pacheenetts, which I have included in Barclay Sound,

also inhabit Port San Juan.

All these are fish-eating Indians, though they get at times a great deal

of venison as well. The fish taken by them are salmon, halibut, cod,

rock-cod, a large pink fish, in shape something like a rock-cod,

herrings, smelt, kou-li-kim and clams. All these are eaten fresh, and

are also dried. But although these are the fish best known to us and

most commonly bought by us from them, the Indians feed upon the whale,

porpoise or sea-hog, seal, sea-lion, sea-cow or fur-seal; sardine,

cuttle-fish, squad, &e.; sea-cucumber or trepang; crabs, muscles,

cockles and clams.

For animal food they have fallow, rein, and elk deer; mountain-goat,

mountain-sheep (in British Columbia only); beaver, bear, lynx or wild

cat, badger, sea-otter.

They also eat esculent roots, sap of trees, and various oils from the

wdiale, seal, porpoise, and hou-li-kun; deers’-tallow, goats’-tallow,

and bears’-grease.

The following land and sea fowl are also taken by them in large

quantities:—Cranes, swrans, grey or Canada goose, white or snow goose,

langley, stock-duck (like our wild duck), widgeon, teal, black duck,

surf-duck, velvet duck; partridges, plover, sand-larks, snipe,

sea-parrots, sea-hens, curlew, oyster-catchers, dovekils, gulls. The

eggs of almost all these birds, and the spawn of fish, especially salmon

and herring, are also much eaten. The latter is collected in large

quantities and spread in the sun to dry. I never saw it used fresh.

Potatoes are now grown at almost all the villages in large quantities.

The Inchans have a favourite dish at then' feasts, which appears to

answer to the carva of the South Sea Islands. They bring canoe-loads of

snow and ice, and with these ingredients are mixed oil, and molasses if

they have it: the slaves and old women being employed to beat it up,

which they do in large howls, until it assumes the appearance of whipped

cream, when all attack the mess with their long wooden spoons. Neither

animals nor fish are eaten raw, except at certain ceremonials and

festivities, which I shall presently describe. Venison, or indeed meat

of any kind, is seldom dried or preserved on the coast, the quantity

obtained being so small and the Indians eating so much flesh when they

can get it, that it is devoured at once or sold at an adjoining

settlement. Of their eating meat in large quantities, I speak from

personal experience when travelling with them. When a deer or elk is

killed they divide the meat pretty fairly, and, the first time they

halt, cook it all in lumps three or four inches square; they then spit

all the pieces on a stick and secure it on their backs, leaving one end

within reach over the shoulder. As they walk along they every now and

then pull a piece off the end of the stick and eat it, and in a few

hours the whole is gone. In the season when bears are fat (midsummer)

the Indian prefers their meat to venison.

They rely mainly upon fish for winter use. They cure it in large

quantities, drying it in the sun and hanging it up in their lodges. A

shell-fish, called Clam, forms a principal article of consumption: it is

like a large cockle, being frequently the size of one’s hand, and with a

smooth shell. They are found on almost all the muddy beaches, a few

inches below the surface, at low water; their whereabouts being always

denoted by a small hole, which they leave open as they imbed themselves

in the mud when the water goes out. Through this hole they keep

-perpetually spouting a small jet of water, making it most unpleasant

work to walk over them. The task of collecting and drying them, as

indeed of preparing all food, devolves principally on the old women and

slaves; and parties of twenty or thirty of them may be seen going about

from beach to beach on this errand, under the charge of two or three

men. They carry baskets and dig them up with their hands or a stick—the

beach, dotted thickly with women in red, green, or dirty-white blankets,

presenting a somewhat picturesque appearance. When a large quantity of

these clams has been collected, they make a pit, eight or ten feet deep;

a quantity of firewood is put in the bottom, and it is then filled up

with clams; over the top is laid more firewood, and the whole is covered

in with fir-branches. In this way they are boiled for a day or more,

according to circumstances. When cooked, they are taken out of the

shells, spitted on sticks, three or four feet long, and exposed to the

sun to dry, after which they are strung on strips of the inner

cypress-bark or pliable reeds, and put away for the winter store. When

the Indians return to their winter villages they are strung along the

beams, forming a sort of inner roof. Some Europeans profess to like

them; but I confess I could never get over their smell, to say nothing

of their taste.

The oil obtained from the hou-li-kun is a common article of food among

the northern tribes, and one of which they are very fond. This fish is

not unlike a sprat, but somewhat longer and rounder, and is so oily that

when dried it will burn like a candle. They are not found at the south

part of the island, but are caught in great numbers to the northward.

The process of extracting the oil from them is very primitive indeed.

Mr. Duncan gives in one of his letters the following description of it,

as witnessed by him at Nass River:—

“In a general way,” he says, “I found each house had a pit near it,

about three feet deep and six or eight inches square, filled with the

little fish. I found some Indians making boxes to put the grease in,

others cutting firewood, and others (women and children) stringing the

fish and hanging them up to dry in the sun; while others, and they the

greater number, were making fish-grease. The process is as follows: make

a large fire, plant four or five heaps of stones as big as your hand in

it; while these are heating fill a few baskets with rather stale fish,

and get a tub of water into the house. When the stones are red-hot bring

a deep box, about 18 inches square (the sides of which are all one piece

of wood), near the fire, and put about half a gallon of the fish into it

and as much fresh water, then three or four hot stones, using wooden

tongs. Repeat the doses again, then stir the whole up. Repeat them

again, stir again; take out the cold stones and place them in the fire.

Proceed in this way until the box is nearly full, then let the whole

cool, and commence skimming off the grease. While this is cooking,

prepare another boxful in the same way. In doing the third, use, instead

of fresh water, the liquid from the first box. On coming to the refuse

of the boiled fish in the box, which is still pretty warm, let it be put

into a rough willow-basket; then let an old woman, for the purpose of

squeezing the liquid from it, lay it on a wooden grate sufficiently

elevated to let a wooden box stand under; then let her lay her naked

chest on it and press it with all her weight. On no account must a male

undertake to do this. Cast what remains in the basket anywhere near the

house, but take the liquid just saved and use it over again, instead of

fresh water. The refuse must be allowed to accumulate, and though it

will soon become putrid and change into a heap of creeping maggots and

give out a smell almost unbearable, it must not be removed. The filth

contracted by those engaged in the work must not be washed off until all

is over, that is, until all the fish are boiled, and this will take

about two or three weeks. All these plans must be carried out without

any addition or change, otherwise the fish will be ashamed, and perhaps

never come again. "So,” concludes Mr Duncan, "think and act the poor

Indians.”

The sea-cucumber, so well known in the South Seas as the Trepang or

Beche do Mer (Ilolothuria tubulosa) is much eaten by the natives.

Captain Flinders, in his ‘Voyage to Terra Australis,’ says it is boiled

and dried, and traded, when thus prepared, with the Chinese. I have

never seen the Red Indians dry it, nor have I ever seen it thus prepared

iu their huts; but I have constantly seen it boiled and eaten fresh. I

once tasted some that was just cooked, and found it had much the same

consistency as India rubber, but without its flavour. The Indians make

some kind of cake of the berries when they are plentiful.

The lichen (L. jubatus) which grows on the pines, is also prepared for

food. Twigs, bark, &c., being cleared from it, it is steeped in water

till it is quite soft; it is then wrapped up in grass and leaves to

prevent its being burnt, and cooked between hot stones. It takes 10 or

12 hours cooking, and when done, while still hot, it is pressed into

cakes. Berries when fresh are eaten in a way we should hardly appreciate

—viz., with seal-oil! I have seen the Indians land from a canoe and pick

a large quantity of beautiful fresh berries, then take a small bowl and

pour into it a lot of seal-oil, and, sitting round it, dip each bunch of

berries into the oil, and eat them with great apparent relish. They

prefer houlikun-oil for this purpose when they can get it.

They have various berries, among them the strawberry and raspberry. They

are always very glad to get bread or rice, and these articles of diet

are generally exchanged with them for fish. I found when travelling that

neither the Coast nor the Inland Indians would ever eat pork. The

.invariable reply to my questions why they did not do so, being “Wake

cumtax Sivasli muckermuck cushom” (Indians do not understand how to eat

pork).

Many of the ducks eaten commonly by the Indian would be found most

unpalatable by white men ; indeed of the 24 species existing in this

part of the world there is only one, the stock-duck, that can be relied

on as being always free from a fishy taste.

None of these tribes are cannibals. An isolated instance of a man who

eats human flesh may be found ; but lie is generally looked upon with

horror and dread by the rest of his people. Still cannibalism is not

altogether unknown among them; and instances may be adduced of wretches,

who have actually exhumed and eaten human corpses.

For drink they are very fond of tea, and always delighted to get it when

travelling, although I have never heard them ask for it in barter. I

remember, on leaving a village in Jervis Inlet where my party had been

sleeping, that the headman came to me and asked for a little tea for his

mother, who, he said, had a bad pain in the face and was very ill. When

they can obtain spirits, they will always get drunk; but I think they

would rather be without them even when they are at work, travelling or

otherwise. I have never yet been asked for spirits by any of a

travelling party, but always for tea; and when I had not enough of that

t© give them, they used to fill up my kettle with water, reboil it, and

drink the miserable decoction with the greatest relish. When they cannot

get tobacco, the Indians will smoke a small leaf like that of the

box-shrub. There is another leaf which they also use for this purpose:

to prepare it they pluck a small bough, hold it over the fire for a few

minutes, then strip the leaves off and rub them in their hands till fine

enough to smoke.

I have previously had occasion to refer to the fashion among the Indians

of carving the faces of animals upon the ends of the large beams which

support the roofs of their permanent lodges. In addition, it is very

usual to find representations of the same animals painted over the front

of the lodge. These crests, which are commonly adopted by all the

tribes, consist of the whale, porpoise, eagle, raven, wolf, and frog,

&c. In connexion with them are some curious and interesting traits of

the domestic and social life of the Indians. The relationship between

persons of the same crest is considered to be nearer than that of the

same tribe; members of the same tribe may, and do, marry—but those .of

the same crest are not, I believe, under any circumstances allowed to do

so. A Whale, therefore, may not marry a Whale, nor a Frog a Frog. The

child again always takes the crest of the mother; so that if the mother

be a Wolf, all her children will be Wolves. As a rule also, descent is

traced from the mother, not from the father.

At their feasts they never invite any of the same crest as themselves :

feasts are given generally for the cementing of friendship or allaying

of strife, and it is supposed that people of the same crest cannot

quarrel; but I fear this supposition is not always supported by fact.

Mr. Duncan, who has considerable knowledge of their social habits, says

that the Indian will never kill the animal which he has adopted for his

crest, or which belongs to him as his birthright. If he sees another do

it he will hide his face in shame, and afterwards demand compensation

for the act. The offence is not killing the animal, but doing so before

one whose crest it is. They display these crests in other ways besides

those I have mentioned, viz., by carving or painting them on their

paddles or canoes, by the arrangement of the buttons on their blankets,

or by large figures in front of their houses or their tombs. They have

another whimsical custom in connexion with these insignia: whenever or

wherever an Indian chooses to exhibit his crest, all individuals bearing

the same family-figure are bound to do honour to it by casting property

before it, in quantities proportionate to the rank and wealth of the

giver. A mischievous or poor Indian, therefore, desiring to profit by

this social custom, paints his crest upon his forehead, and looks out

for an opportunity of meeting a wealthy person of the same family-crest

as himself. Upon his approach he advances to meet him, and when near

enough displays his crest to the unsuspecting victim ; and, however

disgusted the latter may be, he has no choice but to make the customary

offering of property of some sort or other. In this, as in many other

respects, the Indians are so strangely superstitious as to allow

themselves to he imposed upon by their more astute and unscrupulous

brethren. It is common enough for an Indian living by his wits to

circulate a report, some weeks before the commencement of the fish or

berry season, that he has had a dream of a large crop of berries, or

influx of salmon to some particular spot, which he will disclose for a

certain present. He will then go through various ceremonies, such, for

instance, as walking about at night in lonely places ; taking care that

it shall be publicly known that he is “ working on the hearts of the

fish ” to be abundant during the coming season. His supposed influence

over the weather and the inclination of the fish are so readily

credited, that he will in all probability command large prices for his

pretended information and intercession. A canoe’s crew will often give a

third of their first haul to the “fish-priest” to propitiate him, and

ensure good luck for the rest of the season. The prophet of course takes

care to send them to a place where fish are generally found in

abundance; and, even should they be unsuccessful, it is easy for him to

assert that they have done something to offend the Spirits. The habits

of the fish themselves, perhaps, tend to the prevalence of such

superstitious fancies; as they will often quit particular places

altogether for a season, or for several years. Old women, also, often

obtain much influence from the profession of second-sight and the power

of foretelling births, deaths, marriages, famines, &c. Dreams are

generally used as their machinery for these purposes. They also claim

more than the gift of prophecy, and insist that they can prevent people

they dislike from sharing in the success of the others, and in many ways

influence their lives. It is not uncommon to see these old witches

communicating their dreams to the tribe; men and women standing by with

open mouths, and impressed wonder-stricken faces. I take it these poor

old creatures often adopt this profession in the hope of lengthening

their lives; for the Indians are very cruel to the aged, and when they

become useless and burdensome to them will often kill them outright or

leave them on some small desert island to starve. Thus the poor old

creatures will go on gathering clams and berries as long as they can

stand, or making themselves useful in some such way, knowing well that

their lives are not worth much when they cease to work.

The most influential men in a tribe are the medicine-men. Their

initiation into the mysteries of their calling is one of the most

disgusting ceremonies imaginable. At a certain season, the Indian who is

selected for the office retires into the woods for several days, and.

fasts, holding intercourse, it is supposed, with the spirits who are to

teach him the healing-art. He then suddenly reappears in the village,

and, in a sort of religious frenzy, attacks the first person he meets

and bites a piece out of his arm or shoulder. He will then rush at a

dog, and tear him limb from limb, running about with a leg or some part

of the animal all bleeding in his hand, ancl tearing it with his teeth.

This mad fit lasts some time, usually during the whole day of his

reappearance. At its close he crawls into his tent, or falling down

exhausted, is carried there by those who are watching him. A series of

ceremonials obervances and long incantations follows, lasting for two or

three days, and he then assumes the functions and privileges of his

office. I have seen three or four medicinemen made at a time among the

Indians near Victoria, while twenty or thirty others stood, with loaded

muskets, keeping guard all round the place to prevent them doing any

mischief. Although a clever medicine-man becomes of great importance in

his tribe, his post is no sinecure either before or after his

initiation. If he should be seen by any one while he is communing with

the spirits in the woods, he is killed or commits suicide; while if he

fails in the cure of any man he is liable to be put to death, on the

assumption that he did not wish to cure his patient. This penalty is not

always inflicted; but, if he fails in liis first attempt, the life of a

medicine-man is not, as a ride, worth much. The people who are bitten by

these maniacs when they come in from the woods consider themselves

highly favoured.

The ceremony of curing or trying to cure a sick person is very curious.

I give the following description of such a process upon an old woman—a

Tyee—in Slioalwater Bay.

“She had been sick some time of liver-complaint, and finding her

symptoms grow more exaggerated she sent for a medicine-man to ‘ mamoke ’

(work) spells to drive away the ‘memmelose’ or dead people, who, she

said, came to her every night.

“Towards night the doctor came, bringing with him his own and another

family to assist in the ceremony. After they had eaten supper, the

centre of the lodge was cleaned, and fresh sand strewed upon it. A

bright fire of dry wood was then kindled, and a brilliant light kept up

by occasionally throwing oil upon it. I considered this to be a species

of incense offered, as the same light could have been produced, if

desired, by a quantity of pitch-knots, which were lying in the corner.

The patient, well wrapped in blankets, was laid on her back, with her

head a little elevated and her hands crossed on her breast. The doctor

knelt at her feet, and commenced singing a refrain, the subject of which

was an address to the dead, asking them why they had come to take his

friend and mother, and begging them to go away and leave her. The rest

of the people then sang the chorus in a low, mournful chant, keeping

time by knocking on the roof with long wands they held. The burden of

the chorus was to beg the dead to leave them. As the performance

proceeded, the doctor got more and more excited, singing loudly and

violently, with great gesticulation, and occasionally making passes with

his hand over the face and person of the patient, similar to tliose made

by mesmeric manipulators; a constant accompaniment being kept up by the

others with their low chant and beating with their sticks. The patient

soon fell asleep, and the performance ceased. She slept a short time,

and woke refreshed. This was repeated several times during the night,

and kept up for three days; but it was found that the patient grew no

better, and another doctor was sent for, who soon eame with his family

of three or four persons, the first doctor remaining, as the more

persons they have to sing the better.

‘Old John,’ as the last doctor was usually called, had no sooner

partaken of food than he sat down at the feet of the patient, covering

himself completely with his blanket. He remained in this position three

or four hours, without moving or speaking. He was communing with the

‘To-man-na-was,’ or familiar spirit.

“When he was ready, he commenced singing in a loud and harsh manner,

making most vehement gesticulations. He then knelt on the patient’s

body, pressing his clenched fists into her sides and breast till it

seemed to me the woman must be killed. Every few seconds he would scoop

his hands together as if he had caught something, then turning towards

the fire would blow through his fingers, as though he had something in

them he wished to cast into the flames. The fire was kept stirred up, so

as to have plenty of embers, on which, it appeared, he was trying to

burn the evil spirit he was exorcising. There was no oil put on the fire

this time, for the Indians told me they put on oil to light up their

lodge, to let the dead friends see they had plenty, and were happy, and

did not wish to go with them; but now all they wanted was to have the

fire hot enough to bum the ‘skokeen’ or evil spirit the doctor was

trying to expel. The pounding and singing were kept up the same as at

the first performance. Old John sang to his ‘To-man-na-was’ to aid him;

then, addressing the supposed spirit, he by turns coaxed, cajoled, and

threatened to induce him to depart. But all was of no avail, for in two

days the woman died.

At all the feasts the chiefs and heads of families give away and destroy

a great deal of property; this raises them greatly in the estimation of

their own and the people of other tribes summoned to the feast.

Individuals and even tribes will sometimes travel 100 miles or more to

be at the feasts of another tribe. The whole object of amassing wealth,

indeed, seems to be for the gratification of afterwards destroying it in

public. I was at a feast once where 800 blankets were said to have been

destroyed by one man. I saw three sea-otter skins, for one of which 30

blankets had been offered and refused a few days previously, cut up into

little bits about the size of two fingers, and distributed among the

guests. In the interchange of presents the same crests never give to or

receive from each other. I say, in the interchange for in making a

present an Indian always has in view the return that will be made him.

Indeed, should an Indian make you a present at a feast, and you omit to

repay the compliment by presenting him with something equally valuable

at the next feast, he will not hesitate to demand his gift back again.

Mr. Duncan speaks thus of the religious feasts, and, among other

customs, of the destruction of property on such occasions :—

“Their greatest luxury at such times is rice and molasses : their second

dish of importance is berries and grease. Now and then I hear of a

rum-feast being given, which is generally succeeded by quarrelling and

sometimes murder. They are very particular about whom they invite to

their feasts, and, on great occasions, men and women feast separately,

the women always taking the precedence. Yocal music and dancing have

great prominence in their proceedings. 'When a person is going to give a

great feast, lie sends, on the first day', the females of his household

round the camp to invite all his female friends. The next day a party of

men is sent round to call the male guests together. The other day, a

party of eight or ten females, dressed in their best, with their faces

newly painted, came into the Fort-yard, formed themselves into a

semicircle; then the one in the centre, with a loud but clear and

musical voice, delivered the invitation, declaring what should be given

to the guests, and what they should enjoy. In this case the invitation

was for three women in the Fort who are related to* chiefs. On the

following day a band of men came and delivered a similar message,

inviting the captain in charge.

“These feasts are generally connected with the giving away of property.

As an instance, I will relate the last occurrence of the kind. The

person who sent the aforementioned invitations is a chief who has just

completed building a house. After feasting, I heard he was to give away

property to the amount of 480 blankets (worth as many pounds to him), of

which 180 were his own property and the 300 were to be subscribed by his

people. On the first day of the feast, as much as possible of the

property to be given him was exhibited in the camp. Hundreds of yards of

cotton were flapping in the breeze, hung from house to house, or on

lines put up for the occasion. Furs, too, were nailed up on the fronts

of houses. Those who were going to give away blankets or elk-skins

managed to get a bearer for every one, and exhibited them by making the

persons walk in single file to the house of the chief. On the next day

the cotton which had been hung out was now brought on the beach, at a

good distance from the chief’s house, and then run out at full length,

and a number of bearers, about three yards apart, bore it triumphantly

away from the giver to the receiver. I suppose that about 600 to 800

yards were thus disposed of.

“After all the property the chief is to receive has thus been openly

handed to him, a day or two is taken up in apportioning it for fresh

owners. When this done, all the chiefs and their families are called

together, and each receives according to his or her portion. If,

however, a chief’s wife is not descended from a chief, she 'has no share

in this distribution, nor is she ever invited to the same feasts with

her husband. Thus do the chiefs and their people go on reducing

themselves to poverty. In the case of the chiefs, however, this poverty

lasts but a short time: they are soon replenished from the next giving

away, but the people duly grow rich again according to their industry.

One cannot but pity them, while one laments their folly.

“All the pleasure these poor Indians seem to have in their property is

in hoarding it up for such an occasion as I have described. They never

think of appropriating what they gather to enhance their comforts, but

are satisfied if they can make a display like this now and then; so that

the man possessing but one blanket seems to be as well off as the one

who possesses twenty; and thus it is that there is a vast amount of dead

stock accumulated in the camp doomed never to be used, but only now and

then to be transferred from hand to hand for the mere vanity of the

thing.

“There is another way, however, in which property is disposed of even

more foolishly. If a person be insulted, or meet with an accident, or in

any way suffer an injury, real or supposed, either of mind or body,

property must at once be sacrificed to avoid disgrace. A number of

blankets, shirts, or cotton, according to the rank of the person, is

torn into small pieces and carried off.”

The numberless antics practised at these feasts would take far more

space to describe than I can devote to them. I believe, however, there

is some system in them, and that much which appears to us sheer folly

has a meaning and a purpose to these ‘poor creatures. Their sacred

feasts are of several kinds, but the most common is that which takes

place at the commencement of each season, to invoke the aid of the deity

for fine weather, plenty of fish, &c. &c. A glimpse of one of these is

given by the liev. Mr. Garrett (of whom I shall have occasion to speak

hereafter in connection with the missions to the Indians), in a letter

to his brother:—

11 Lee. 16.—When crossing the bridge to the Indian School to-day, I was

astonished by a very loud noise proceeding from one of. the houses of

the Songhies. Guided by the sound, I entered the house to see what was

going on. For a time, so great was the din, I could make nothing of it.

At length, by force of inquiry, and pressing through the crowd to the

front, I witnessed the following scene. A space, about 40 feet by 20

feet, had been carefully swept; three large bright fires were burning

upon the earthen floor; round three sides of this space a bench was

fixed, upon which were packed, as close as they could fit, a crowd of

young women. I do not think there were any men or boys among them, but

there being only the light of the fires, I could not see very

distinctly. Each of these individuals was armed with two sticks. In

front of them, extending all the way round the rectangular space, was a

breadth of white calico. Under this calico the row of sticks exhibited

themselves. Upon the ground, in the corner on my right, was a young man

provided with a good-sized box, which he had fixed upon an angle and

used as a drum. Also, on the ground, still nearer to me, sat an old man

and an old woman; and flat upon the ground, apparently dead, lay a

female chief, with her head reclining in the lap of the old crone; while

around me there stood a motley crowd of all tribes, staring first at me

and then at the stage. All this time the choir upon the benches kept up

a sort of mixture between a howl and a wail, while they beat time upon

the bench with the forest of sticks with which they were armed; our

friend upon the ground making his wooden drum eloquent of noise. It is

utterly vain to attempt to give any description of the terrible noise

which was thus occasioned. This continuing, for about twenty minutes,

the female chief began to show signs of life; first, by a slight motion

of the hands, then of the arms, then of the shoulders, and so on, until

her whole frame became violently agitated; the din and the uproar

increasing in intensity as her agitation increased. At length she shook

herself into a sitting position, when, with hair dishevelled and glaring

eyes, she formed a singularly repulsive spectacle. Her agitation

increased, until there could have been no part of her body which did not

shake— the storm and rattle of sticks and the howling unmeaning wail

steadily keeping pace with her—when, suddenly, at a motion of her hand,

there was an instantaneous silence. They watched her narrowly and her

every motion was observed. Upon a signal they began again, and stopped

as suddenly. At length she got upon her hunkers, and in that not very

graceful position jumped about between the fires. Presently, as her

inspiration increased, she raised herself and ultimately got herself

erect. Having, then, by a series of very ungraceful motions, completed a

journey round the fires, she came to a stand at the end of the rectangle

next which the old man and woman were sitting. . . . This being done,

such a clatter and rattle and yell were raised as nearly deafened me. .

. . My time being now exhausted, I was obliged to leave this strange but

interesting scene.

“It was refreshing to breathe the sea-air again and gaze upon the light

of day, after emerging from so unearthly a place. Pursuing my way, I met

a man carrying two large boilers. I cross-examined him, and ascertained

that the female chief, who was playing her part within among the women,

would presently give an abundant feast of wild-fowl to all the men, and

that he was bringing down the boilers to cook the same. He further

stated that all the men were assembled in his house, awaiting the gift,

and that, if I wished, he would gladly show me where they were. I

accompanied

t him joyfully. I found a very large house, carefully swept, with

several good fires burning brightly upon the earthen floor, and about

fifty or sixty men assembled, in patient expectation of the birds. I

inquired into the nature of the musical entertainment going on. They

told me that was their “Tamanoes,” or sacred feast; that they always

played and danced so during the latter half of the last month in the

year; that they did so for two reasons—first, to make their hearts good

for the coming year, and secondly, to bring plenty of rain, instead of

snow; that if they did not do so, a great deal of snow would come, and

they should be very much afraid.”

At their grand feasts and ceremonies some of the chief men wear very

curious masks and dresses—the former composed of the heads of animals

decorated with feathers, and painted various colours. At Fort Rupert,

“Whale,” one of the Quav-guult chiefs, showed me his masks, which he

kept carefully locked up in a large box. One in particular was most

extraordinary: it was a wooden head, large enough to take his own inside

easily, and I think meant for an eagle; the mouth was very large, and

could be opened by strings, which were carried through the top of the

mask and down the back, so as to be worked by the wearer’s hands. I have

seen others with strings to make the wings flaj3, and to turn the head

from side to side.

On all occasions of peace-making, whether it be feast or palaver, the

chiefs cover their heads with eagles’ down and scatter it about them and

over the person with whom they are making peace. I have seen this done

on several occasions and under different circumstances. With them, as

with us, white always denotes peace. For example, the Indians, whom we

employed on board as interpreters, always put white feathers in their

caps when going among a strange tribe. Mr. Duncan also speaks of this

occurring at their reception of him on two different occasions.

He says:—“Much to my sorrow, he (the chief) put on his dancing-mask and

robes. The leading singers stepped out, and soon all were engaged in a

spirited chant. They kept excellent time by clapping their hands and

beating a drum. (I found out afterwards that they had been singing my

praises, and asking me to pity them and do them good.) The chief

Kahdoonahah danced with all his might during the singing. He wore a cap

which had a mask in front, set with mother-of-pearl and trimmed with

porcupine-quills. The quills enabled him to hold a quantity of white

birds’ down on the top of his head, which he ejected while dancing by

jerking his head forward; thus he soon appeared as if in a shower of

snow. In the middle of the dance a man approached me with a handful of

down and blew it over my head, thus symbolically uniting me in

friendship with all the chiefs present and the tribes they severally

represented.”

On another occasion he says:—“The usual course was pursued. Kinsahdad

dressed himself up in his robes, and then danced while the people sang

and clapped their hands. During the performance I was nearly covered

with white downy feathers. A man, after having feathered Kinsahdad’s

head, came and blew'a handful over me. One great feature of the dance

was that the performer should keep a cloud of feathers flying about his

guest. It was done in this way : the dancer, after making a graceful

approach, would commence a retreat, still keeping his face toward me,

and, in perfect time with the song and clapping of hands, jerk his head

forward at every step, and thus keep a quantity of feathers flying from

his head-dress.”

The reader will notice in these extracts, and in all that has been said

about the Indian feasts, a curious distinction between the customs of

the West and those of the East. Here it is always the men, and the chief

men, who dance and take a part in all the antics, while in the East the

women are the performers. I have never seen an Indian woman dance at a

feast, and believe it is seldom if ever done. The young men sit round

and look on with awe at what Easterns would regard as beneath the

dignity of man. So with work: the woman of the West is a slave,

performing the most menial offices, while the woman of the East lives a

life of luxurious idleness.

On missions of peace also this down is, as I have said, made use of. One

day in talking to Mr. Bamfield, the Indian agent on the West coast of

Vancouver Island, who has resided among the Ohyat tribe several years,

we were comparing many of the Indian customs with those of Europe, and

he told me that on the occasion of a quarrel between the Ohyat and

another tribe, a chief, who was one of the best speakers among them, was

employed for several days as envoy, going frequently to the enemy’s camp

to negociate, and that his diplomacy averted war. During the whole time

of the negociations the peace-maker wore eagles’ down all over his head,

so that he looked as if he had been powdered, and eagles’ feathers in

his cap, or secured to a band round his head. I remember Mr. Bamfield

mentioning another occasion, on which they came to blows, as

illustrative of the systematic method of their approach and attack. The

Ohyats and Nootkas joined forces against the Clayoquots; and Mr.

Bamfield accompanied them part of the way. When they approached the

Clayoquot village they were to attack, they put into a sandy beach and

lauded: the chiefs then held a consultation with those who knew the

place best, and having hit upon a young man who had a Clayoquot wife,

told him to draw a plan of the place on the sand. He commenced by

marking out the grouud, then the houses ; describing the partitions in

them, how many men were in each, whether they were brave or cowardly: in

fact, -describing the place accurately. They then divided the work

between the two tribes, and, standing back to back some little way

apart, the chiefs told off each man to his duty. Everything, he said,

was perfectly arranged. Till attack was, however, not successful, as the

Nootkas failed in their part and would not leave their canoes. The

Ohyats took 18 heads, and lost about the same number. The cause of the

war was that the Clayoquots had murdered a white man, and tried to put

the blame on the others, among whom he was living.

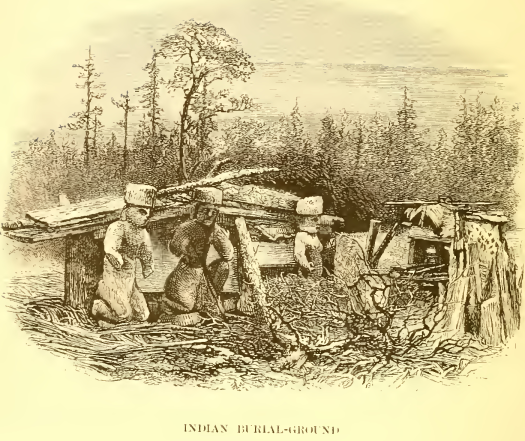

As a rule, the Indians

burn their dead, and then bury the ashes. The mode of depositing these

remains differs even among members of the same tribes. Sometimes they

are buried in the ground, sometimes in trees, in boxes or in canoes.

There is, I think, no rule or rules observed in sepulture. I have seen

more suspended among the branches of the trees than buried in the

ground, but their mode of sepulture depends very much upon convenience

and circumstances. More are laid on the ground than in it, for the

Indians have, I believe, a decided objection to interment —whether from

any idea of a resurrection or not, I cannot say. When buried on the

ground, they are generally placed among the bushes on some small islet,

and the top of the box is always covered with large stones. We used

quite commonly to come across the bleached bones when putting up

surveying-stations. It is very common for a man’s property to be buried

with him, or suspended over his grave. In the case of great men the

latter course is, I think, chosen generally for the purpose of showing

their wealth. I have seen the grave of a chief inland with a number of

blankets cut in strips hanging over it, several pairs of trowsers, and

two or three muskets. At Nanaimo there is a small hut built over the

remains of the late chief. In the case of a chief it is also customary

to paint or carve his crest on the box in which his bones lie, or to

affix it on a large signboard upon a pole or neighbouring tree. Mr.

Duncan says that if the crest of the deceased happens to be an eagle or

a raven, it is usual among the Northern Indians to carve it in the act

of dying—the bird being affixed to the edge of the box with its wings

spread, so that it appears to a passer-by as if just about to leave tlie

coffin; and be (Mr. Duncan) very naturally asks whether this may come of

any knowledge of a resurrection of the dead among the Indians.

They will not usually let strangers witness the burial of their dead. It

was at one time not uncommon for Indians to desert for ever a lodge in

which one of their family had died; but this rarely, if ever, happens

now.

The rites of mourning are carried out strictly, but not until the corpse

is buried. After this, at sunrise and sunset, they wail and sing dirges

for the space of some thirty days.

I never witnessed a funeral myself; but I think that, except when the

person to be buried is of some rank, there is very little ceremony.

At Fort Simpson it appears to be the regular custom to burn the dead,

but this is departed from in some cases; for Mr. Duncan mentions

witnessing a funeral there from the Fort Gallery. He says : “The

deceased was a chief’s daughter, who had died suddenly. Contrary to the

custom of the Indians here (who always burn their dead), the chief

begged permission to inter her remains in the Fort Garden, alongside her

mother, who was buried a short time ago, and was the first Indian thus

privileged. The corpse was placed in a rude box, and borne on the

shoulders of four men. About twenty Indians, principally women,

accompanied the old chief (whose heart seemed ready to burst) to the

grave. A bitter wailing was kept up for three-quarters of an hour,

during which time about seven 01* eight men, after a good deal of

clamour (which strangely contrasted with the apparent grief of the

mourners), fixed up a pole at the head of the grave, on which was

suspended an Indian garment. At the bead of the mother’s grave several

drinking-vessels were attached, as well as a garment.

It is certain that the Indians have some idea of a Superior Being; and

this idea, no doubt, dates before the appearance of any priests among

them. They believe, too, that thunder is his voice. I remember on one

occasion, when I was travelling in a canoe during a violent

thunderstorm, that, at each peal, all the rowers rested on their

paddles, and said a prayer, taught them, no doubt, by the Romish

priests, and I could not get them to paddle on till they had finished

it.

After a storm on the coast, they always search for dead whales, and seem

to connect them in some way with thunder. It is very difficult indeed to

get at any of their traditions, and still more difficult to distinguish

between their own standard doctrines and the teaching of the priests.

One of the settlers on the west coast of Vancouver Island, who has been

there for a number of years, told me that there was at Ohyat a carving

of two eagles with a dove in their centre and two serpents in the rear,

with a whale seemingly seeking protection from the serpents. This

carving representing thunder, under its native name Tuturrh, was held in

great respect by them. An old half-breed once told me that one of their

legends was that crows were white once, but were made black by a curse:

what they had done to deserve this punishment I could not ascertain.

The Indians appear generally to have some tradition about the Flood. Mr.

Duncan mentions that the Tsimsheans say that all people perished in the

water but a few. Amongst that few there were no Tsimsheans; and now they

are at a loss to tell how they have reappeared as a race. In preaching

at Observatory Inlet he referred to the Flood, and this led the chief to

tell him the following story. He said: “We have a tradition about the

swelling of the water a long time ago. As you are going up the river you

will see the high, mountain to the top of which a few of our forefathers

escaped when the waters rose, and thus were saved. But many more were

saved in their canoes, and were drifted about and scattered in every

direction. The waters went down again ; the canoes rested on the land,

and the people settled themselves in the various spots whitlier they had

been driven. Thus it is the Indians are found spread all over the

country; but they all understand the same songs and have the same

customs, which shows that they are one people.”

Schoolcraft, the American writer, in his ‘History of the Indians,’

narrates a similar tradition, which is found current on the east side of

the Rocky Mountains.

As their languages become more known, many other legends and traditions

will doubtless come to light; but I must not conclude this notice of

them without reference to the most interesting yet known, viz., a belief

in the Son of God. “This [Observatory Inlet] being (says Mr. Duncan) a

noted place, the Indians have several legends connected with the various

objects about. I listened to some, and remarked that in most of them the

Son of the Chief above occupies the place of benefactor or hero, and

most of the acts ascribed to him are acts of mercy. It was he, they say,

that first brought the small fish to this inlet for them, which now

forms one of their principal articles of food.”

As I have before said, the Roman Catholic priests have, so far as

regards forms and the observance of certain religious customs, done a

good deal among them. I remember one Sunday in Port Harvey, Johnstone

Strait, when we were all standing on deck, on a bright sunny morning

just before church-time, looking at six or eight large canoes which hung

about the ship, they suddenly struck up a chant, which they continued

for about ten minutes, singing in beautiful time, their voices sounding

over the perfectly still water and dying away among the trees with a

sweet cadence that I shall never forget. I have no idea what the words

were, but they told us they had been taught them by the priests. The

Roman Catholic priest, indeed, has little cause to complain of his

reception by the Indians. On the west coast, at a place where the priest

had been before, but had not time to revisit them, he sent his

shovel-hat in the canoe in his stead; and upon its arrival the whole

village turned out, shouting “Le Pretre! Le Pretre!” and had prayers at

once upon the spot. I have seen other Indians, on the priest’s arrival

among them, cease their fishing and other occupations, and hurry to meet

him.

At Esquimalt all the Indians attend the Romish mission on Sunday

morning, and at eight o’clock the whole village may be seen paddling

across the harbour to the mission-house, singing at the top of their

voices. Certainly the self-denying zeal and energy with which the

priests labour among them merit all the success they meet with. To come

upon them, as I have done, going from village to village alone among the

natives, in a dirty little canoe, drenched to the skin, forces

comparisons between them and the generality of the labourers of other

creeds that are by no means flattering to the latter.

Perhaps the worst failing of the Red man, next to his love of

fire-water, is his passion for gambling. Most of them will gamble away

everything they have—houses, wives, property, all are staked upon the

chances of their favourite games. If in passing their village at night

you leave them sitting in a ring gambling, the chances are that, upon

your return in the morning, you will find them at it still. I have only

seen two games played by them, in both of which the object was to guess

the spot where a small counter happened to be. In one of these games the

counter was held in the player’s hands, which he kept swinging backwards

and forwards. Every now and then he would stop, and some one would guess

in which hand he held the counter, winning of course if he guessed

right. The calm intensity and apparent freedom from excitement, with

which they watch the progress of this game is perfect, and you only know

the intense anxiety they really feel by watching their faces and the

twitching of their limbs. The other game consisted of two blankets

spread out upon the ground, and covered with saw-dust about an inch

thick. In this was placed the counter, a piece of bone or iron about the

size of half-a-crown, and one of the players shuffled it about, the

others in turn guessing where it was. These games are usually played by

ten or twelve men, who sit in a circle, with the property to be staked,

if, as is usual, it consists of blankets or clothes, near them. Chanting

is very commonly kept up during the game, probably to allay the

excitement. I never saw women gamble.

The Indians are well known to be polygamists, but I believe that a

plurality of wives is general only among the chiefs of tribes, the rest

being commonly too poor to afford this luxury. No other cause for any

such abstinence on their part exists. When Mr. Stain was the Colonial

Chaplain at Victoria, the chief of the tribe residing there went to him

for some medicine for his wife, who was ill. He gave him something which

cured her, and, to the astonishment of the chaplain and his family, a

day or two afterwards the chief came to his house, leading his wife by

the hand, and, in gratitude for her recovery, presented her to his

benefactor. On being remonstrated with, I believe, by the chaplain’s

wife, who objected, not at all unnaturally, to the nature of the

offering, he said it was nothing, not worth mentioning in fact, as he

could easily spare her, she being one of eleven!

I have said that intrigue with the wives of men of other tribes is one

of the commonest causes of quarrel among the Indians. This is not

surprising, when it is considered, among other things, that marriage is

entirely a buying and selling process, and the bargain is frequently

made when the principals are children. The man or his friends give so

many blankets for the wife, while yet a child. If when she grows up she

refuses to marry the man who has purchased her, she or her friends must

return all the property paid for her; if they cannot do this, she is

obliged to go to the buyer. There is generally a feast at the wedding of

any one of importance in a tribe; but this, I think, depends entirely on

the wealth of bride and bridegroom, much as in our own country.

In appearance the

Indians of Vancouver Island have the common facial characteristics of

low foreheads, high cheekbones, aquiline noses, and large mouths. They

all have their heads flattened more or less; some tribes, however,

cultivating this peculiarity more than others. The process of flattening

the head is effected while they are infants, and is very disgusting. I

once made a woman uncover a baby’s head, and its squashed elongated

appearance nearly made me sick. By far the most flattened heads belong

to the tribe of Quatsiuo Indians, living at the north-west end of the

island. Those who have only seen the tribes of the east side of the

island may be inclined to think the sketch of this girl exaggerated, but

it was really drawn by measurement, and she was found to have 18 inches

of solid flesh from her eyes to the top of her head. It does not appear

that the process at all interferes with their intellectual capacities.

Among some of the tribes pretty women may be seen: nearly all have good

eyes and hair, but the state of filth in which they live generally

neutralises any natural charms they may possess.

Half-breeds, as a rule, inherit, I am afraid, the vices of both races: I

speak of the uneducated half-breed, to whose Indian abandonment to vice

and utter want of self-control appears to be added that boldness and

daring in evil which he inherits from his white parent.

The Indian’s head is generally large, often so large as to be somewhat

out of (proportion to the rest of liis frame. Men and women both part

their hair in the middle, and wear it long, hanging over the shoulder.

The hair is generally good, but so neglected that it looks, and is, very

dirty. The custom of painting prevails among all Indians in North

America. They paint the face in hideous designs of black and red (the

only colours used), and the parting of the hair is also coloured red. I

have seen them when travelling, and when I knew they had not washed for

three weeks, take the greatest pains in colouring their faces, oiling

their hair with fish-oil, and painting the parting. The northern males

sometimes wear their hair cut short, or rolled up into a sort of hall on

the top of the head ; but the southern tribes consider it a disgrace to

have short hair. A Barclay Sound lad, whom we took on board the

‘Hecate,’ and who had been persuaded to have his hair cut, said he could

not go back to his tribe until it had grown again.

The men very seldom have beards or moustaches, and are in the habit of

pulling out any hair that appears on their faces. This beardlessness

appertains to almost all the North American Indians, and I believe not

to them only, as the natives of the Congo, who are very fine men, have

no hair on their faces. The hair of their heads is almost always dark

brown, though sometimes an Albino is seen with quite white hah. The

strong feature in all their faces is their eyes, which are nearly always

fine, and among the half-breeds very beautiful.

Their constant diet of dry fish, &c., has the curious effect of

destroying the teeth, so that you hardly ever see an Indian over middle

age with any visible, having worn them down level with the gums.

Some Indians, especially the tribes of Queen Charlotte Islands, carve

very well, and much of their leisure time is spent in decorating their

canoes and paddles, making dishes and spoons in wrood or slate,

bracelets and rings of metal. They make busts out of whales’ teeth, that

are in some cases very faithful likenesses. Like the Chinese, they

imitate literally anything that is given them to do; so that if you give

them a cracked gun-stock to copy, and do not warn them, they will in

their manufacture repeat the blemish. Many of their slate-carvings are

very good indeed, and their designs most curious.

One of their strangest prejudices, which appears to pervade all tribes

alike, is a dislike to telling their names—thus you never get a man’s

right name from himself; but they will tell each other’s names without

hesitation.

I have previously mentioned that slavery is universally practised among

these tribes, and the subsequent extracts from Mr. Duncan’s Journal will

show with what horrid cruelty their captives are treated—indeed, it

often happens that some crime is atoned for by a present of three or

four slaves, who are butchered in cold blood.

I have also spoken of the intense hatred of them all for the “Boston

men.” This hatred, although caused chiefly by the cruelty with which

they are treated by them, is also owing in a great measure to the system

adopted by the Americans, of moving them away from their own villages

when their sites become settled by whites. The Indians often express

dread lest we should adopt the same course, and have lately petitioned

Governor Douglas on the subject.

Their phraseology abounds in highly figurative and flowery expressions.

It is so little known, however, as yet, that anything like an accurate

account is impossible. In illustration, I will, however, quote from Mr.

Duncan’s Journal an account given him by an Indian, of the first

appearance of white men among his people, the Keethratlah Indians, near

Fort Simpson. “One very old man,” he writes, “with characteristic

animation, related to me the tradition of the first appearance of the

whites near this place. It was as follows:— A large canoe of Indians

were busy catching halibut in one of these channels. A thick mist

enveloped them. Suddenly they heard a noise as if a large animal were

striking through the water. Immediately they concluded that a monster

from the deep was in pursuit of them. With all speed they hauled up

their fishing-lines, seized the paddles, and strained every nerve to

reach the shore. Still the plunging noise came nearer. Every minute they

expected to be ingulphed within the jaws of some huge creature. However,

they reached the land, jumped on shore, and turned round in breathless

anxiety to watch the approach of the monster. Soon a boat filled with