|

The Four Thousand

Muskets at the City Hall

THE troubles known to

history as the Mackenzie Rebellion are really divisible into two

distinct periods. First, the rebellion itself before it became an

international affair; and secondly, the Mar of Filibusters that began

with the burning of the Caroline on December 29th, 1897. 'The success or

failure of Mackenzie's attempt to overthrow the government of Sir

Francis Head did not depend on any preponderance of loyalty or

disaffection, but on something very material and confined in a very

small space—namely on the four thousand stand of arms lying in their

unbroken packages at the City Hall in Toronto. Let us see why.

Of all the governors who by the blunder of a statesman (or the mistake

of a messenger) 1 have vexed Britain’s over-seas dominions, Sir Francis

Bond Head was by the quality and exercise of his undoubted talents the

best fitted to lose a British Colony.

While exasperating the Reformers to the verge of rebellion, he was

scarcely less irritating to the upholders of the Family Compact, who

found him resentful of their advice and determined to pull the roof down

over his own and their heads. The reform agitation had up till August

15th, 1837, been a spirited, but not overtly unlawful propaganda by

public meetings and white-hot publications. About this date some fifty

Orangemen with clubs adjourned one of Mackenzie’s meetings. The answer

to this line of argument took the form of an escort of one hundred

horsemen, who accompanied the agitator to his Vaugh&n meeting.

The project launched by Mackenzie in July for uniting, organizing and

registering the Reformers of Upper Canada as a political union,’ began

as he foresaw to take a military direction. The various branches or

societies, which he had instituted, began to take an unwonted interest

in rifle matches and turkey shoots and to collect pike-heads, doubtless

for their symbolic value.

These matters were duly reported to Sir Francis Head, who secure in his

sense of popularity, not only refused to take any precautions to meet an

outbreak, but in spite of the most alarming information sent every

regular soldier out of the province to help against Papineau in Quebec.

The garrison having disappeared, the insurgents had two chances to get

the four thousand muskets upon whose possession depended the fate of an

appeal to arms. Mackenzie, while disclaiming

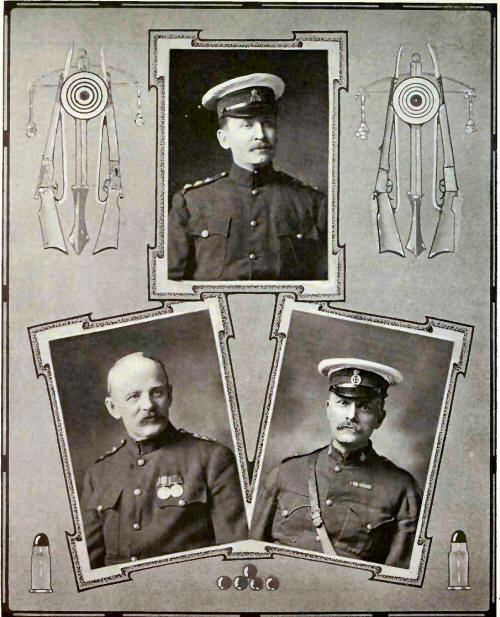

Capt. W. B. Hamilton, Commanding A

Company, Capt. W. H. Taylor, Commanding B Company Capt W. G. Fowler,

Commanding C Company.

a military capacity

knew the general scarcity of tire arms,3 and proceeded in his

characteristic way to improve his first chance of getting that

superiority of fire which determines battles. His plan was “that we

should instantly send for Dutcher’s foundry-men and Armstrong’s

axe-makers, all of whom could have been depended on, and with them go

promptly to the Government House, seize Sir Francis, carry him to the

City Hall, a fortress in itself, seize the arms and ammunition there and

the artillery, etc., in the old garrison; rouse our innumerable friends

in town and country, proclaim a provisional government,” etc., etc.

Viewing the matter in the light of what actually did happen, one is

struck by the entire feasibility of the plan and by the utter imbecility

displayed by Mackenzie in his method of execution. For instead of going

himself with a few tried friends, and collecting Dutcher’s and

Armstrong’s men, he propounded his manoeuvre to a meeting of fourteen or

fifteen of the most fluent and sub-heroic orators in his party; with the

result that they talked it out until it joined the innumerable list of

great deeds that might have been done.

Inevitably some one told Sir Francis Head and consistently with his

character he would neither do anything himself, nor permit anyone else

to do anything for the defence of his person, capital or province.

About this time there was in Toronto a certain veteran soldier of 1812,

Col. Fitzgibbon, who was making an unqualified nuisance of himself to

the powers-that-be. He made repeated alarmist representations to Head

and his Council of an impending rebellion and was loftily snubbed by the

Governor, the Judges and the Attorney-General. Indeed the only man of

official standing in Toronto that gave heed to his utterances appears to

have been Hon. Win. Allan, whom we have mentioned in his militia

capacity in previous chapters. Despite his chilling lack of

encouragement, Fitzgibbon got up a list of one hundred and twenty-six

men (out of the twelve thousand inhabitants of the city) upon whose

loyalty lie could depend. Taking this list to Sir Francis he informed

him that with or without his permission he intended to keep these men on

duty so that on the ringing of the college bell they should assemble at

the City Hall. When the matter was presented to him in this manner Sir

Francis gave a grumbling assent. As a matter of history this little

contingent was all that stood between Head and the successful issue of

Mackenzie’s second plan for the capture of the four thousand muskets.

This plan was one of those intricate combinations which can only succeed

in the entire absence of any military precaution or capacity on the part

of those who are to be overthrown. Mackenzie schemed to concentrate his

followers from Dan to Beersheba at a point in York County, and march

thence upon the city before the Government, could collect its friends.

The date fixed a as Thursday, 7th December, 1837, and Montgomery’s

Tavern on Yonge Street was the rendezvous.

Two unforeseen circumstances broke lip the combination. The first was

that Dr. Rolph, a brilliant orator and bad conspirator, got alarmed at

the state of unrest in Toronto, and thinking the plan had been

discovered changed the date to the 4th December. This had the result

that only a portion of the would-be-rebels got notice in time to join

Mackenzie. The others either went out later with Dr. Duncombe in the

west, and being practically unarmed, dispersed without battle; or

hastening to the scene of trouble and hearing of the fiasco at

Montgomery’s Tavern became forthwith Her Majesty’s most loyal militia.

The other circumstance was that the irrepressible Fitzgibbon despite the

most explicit order of Sir Francis Head posted a forbidden and unthanked

picket on Yonge Street.

On Monday, the 4th December, 1837, the Rebellion actually broke out and

on Tuesday night the rebels, having been amused for several hours by

flags of truce, moved down Yonge Street to take the city. Their advance

guard struck the picket commanded bjp Sheriff 1\ Ik Jarvis. The picket

fired and ran in. The rebels also ran,—some eight hundred of them,- and

retired to Montgomery’s Tavern. To put it mildly the city was alarmed;

even Sir Francis Head dressed himself and added to the confusion at the

City Hall by issuing absurd orders. The arrival of Allan McNab from

Hamilton with sixty men of Gore saved the situation by distracting the

attention of Sir Francis from the confusion he was maintaining. The

subsequent events—the. advance of the now numerous volunteers with,

their muskets and cannon against the rebels of whom but two hundred had

fire arms; the foregone conclusion at Montgomery’s Tavern,—these are now

ancient history.

Now where among all this confusion was the militia of whom as we have

seen there were among the notables of the province such numerous

colonels, lieutenant-colonels, majors and captains (not to mention one

lieutenant). It seems, indeed, that these great men were not without the

spirits of soldiers even if the bodies were invisible. For an

eye-witness of the scene at the Market Place in Toronto on the morning

of the 5th December, after the college bell had rung during the night,

writes:—"I found a large number of persons serving out arms to others as

fast as they possibly could. Among others, we saw the

Lieutenant-Governor in his every-day suit with one double barrelled gun

in his hand, another leaning against his breast and a brace of pistols

in his leathern belt. Also Chief Justice Robinson, Judges Macaulay,

Jones and McLean, the Attorney-General and Solicitor-General with their

muskets, cartridges, boxes and bayonets, all standing in ranks as

private soldiers under the command of Col. Fitzgibbon.”

A spirited description of the militia man of 1837 is to be found in

Lindsay’s “Life of Mackenzie”:

“The militia who went to the succor of the Government was not generally

a more warlike body of men than the insurgents under Fount.6 These were

drawn from the same class—the agriculturists- and were similarly armed

and equipped A description of a parly as given to me by an eye-witness-

who came down from the North, would answer, with a very slight

variation, for the militia of any other part of the province. A number

of persons collected at Bradford, on the Monday or Tuesday, not

one-third of whom had arms of any kind; and many of those who were armed

had nothing better than pitchforks, rusty swords, dilapidated guns, and

newly manufactured pikes, with an occasional bayonet on the end of a

pole. These persons, without the least authority of law, set about a

disarming process; depriving every one who refused to join them, or whom

they chose to suspect of disloyalty, of his arms. Powder was taken from

stores, wherever found, without the least ceremony, and without payment.

On Thursday, a final march from Bradford for Toronto was commenced; the

number of men being nearly five hundred, including one hundred and fifty

Indians, with painted faces and savage looks. At Holland Landing some,

pikes, which probably belonged to Lount, were secured. In their

triumphant march, these grotesque-looking militiamen made a prisoner of

every man who did not give such an account of himself as they deemed

satisfactory. Each prisoner, as he was taken, was tied to a rope; and

when Toronto was reached a string of fifty prisoners all fastened

together were marched in. Tearing an ambush, these recruits did not

venture to march through the Oak Ridges in the night; and a smoke being

seen led to the conclusion that Toronto was in flames. McLeod’s tavern,

beyond the Ridges, was taken possession of, as well as several other

houses in the vicinity. In a neighbouring store, all kinds of provisions

and clothing that could be obtained were unceremoniously seized. At the

tavern there was a regular scramble for food; and cake-baking and

bacon-frying were going on upon a wholesale scale. Next morning, several

v ho had no arms, and others who were frightened, returned to their

homes. Each man wore a pink ribbon on his arm to distinguish him from

the rebels. Many joined from compulsion; and a larger number, including

some who had been at Montgomery's, suddenly turned loyalists when they

found the fortunes of the insurrection had become desperate. When they

marched into Toronto, they were about as motley a collection as it would

be possible to conceive.

“Such was the Canadian militia in 1837, at a time when Sir Francis Bond

Head had sent all the regular troops out of the province.’’

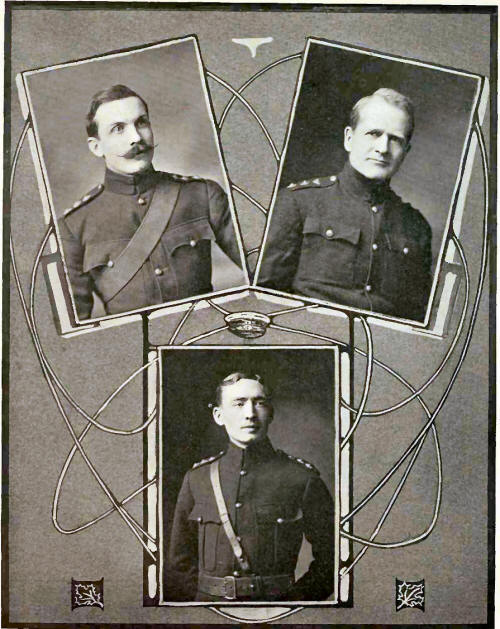

Capt. B. H. Brown, Commanding F Company, Capt. A. T. Hunter,

Commanding G Company, Capt. S. E. Curran, Commanding H Company |