|

How the York Militia

went with Brock to Detroit, and how Peter Robinson’s Rifle Company kept

Tryst

ONE day in the later

part of July, 1812, General Brock called out the York Militia on

Garrison Common. The days previous to this parade had been filled with

anxious preparation by the flank companies, who were anticipating the

event and by extraordinary exertions on the part of the General himself.

The American General Hull had proceeded to take possession of Western

Canada in a Proclamation to the Inhabitants, in which he threatened to

emancipate them from tyranny and oppression and restore them to the

dignified station of freemen. This had been answered by a counter

Proclamation from Brock (prepared by the facile pen of Mr. Justice

Powell), and by a small expedition sent under Capt. Roberts to capture

Mackinac.

The proclamations on either side were barren of result, but the Mackinac

expedition proving a complete success the weight of argument remained

with the British.

On July 12th, simultaneously with his proclamation, Hull commanding a

formidable army described by himself as “a force which will look down

all opposition,” crossed over to Sandwich, where he planted the American

standard. His subsequent performance was characterized by feebleness in

action and even against the scanty forces that could be collected to

delay him, his looking down of opposition did not take him beyond the

little river Canard, where a handful of troops, militia and Indians

damped his military aggressiveness.

News of this invasion having reached Toronto, General Brock with a party

of soldiers rowed across the Lake to Niagara to put the frontier there

in such a state of defence as means permitted; and immediately rowed

back in the same boat and called out the militia.

The proposal that the General had to make must have seemed not much more

seductive than the privilege of the three hundred Lacedemonians to

occupy Thermopylae. He declared his intention to take an expedition from

what is now Port Dover and proceed thence by boats to Amherstburg. But

owing to the limited transportation at his command he could only take

one hundred volunteers from York, the same number from the head of the

Lake (now Hamilton) and an equal number from Port Dover. He called for

volunteers; many more men volunteered than could be taken and all the

officers. From that hour Brock was not and Britain never need be in

doubt as to what response will be given by the Canadian militia.

Capt. Howard, of the 3rd Yorks, was selected to command the one hundred

men of York, and under him were detailed for duty Lieut. John Beverley

Robinson, of his own flank company; Lieut. Jarvie, of Cameron’s Company,

and Lieut. Richardson, of Selby’s flank company of the 1st Yorks.

Captain Peter Robinson also of the 1st Yorks, was by a special act of

grace permitted to take his company of riflemen overland to the scene of

action,—it being hardly suspected that he could ever succeed in arriving

before the matter would be decided.

The little force left York on August 6th for Burlington Bay and picking

up the other Yorks from that region marched overland to the rendezvous.

On the way thither Brock dropped a word in the ear of the Six Nation

Chiefs. And this by the way is one answer to the critics of Brock’s

aggressive strategy. For both Americans and British were much solicitous

about those formidable skirmishers, the Indians; each side trying to

persuade the astute chiefs that it possessed an overwhelming

superiority. The chiefs on the other hand, mindful of the teachings of

recent history, before committing their warriors to an unqualified

support of England, required to be shown that the British officers were

in earnest and meant to defend Upper Canada tooth and nail. The march

past of Brock with his scarlet coated militia0 was to the practical

Indian several hundred eloquent and convincing orations to stand by his

ally the King.

To us familiar with the ease in which now a trip can be made in a few

hours from Toronto to Detroit it seems strange that so energetic a

general should commit his force to a waiter trip of two hundred miles on

a huge and treacherous lake rather than continue his march westward

until he reached the Liver. Nor does the wonder diminish when we find

that the lake boats collected for his expedition were not such luxurious

craft as we entrust ourselves to at this day when tempting the waters of

the Great Lakes, but the open boats or batteaux of that day propelled by

the steady sweep of the long two-handed oar.

But when we read of what toils befell overland passengers, in the many

days it took them to win from the Detroit to the Grand through a forest

land, where the streams had no bridges6 and the roads no existence, we

can well understand why Brock took the dangerous water route and with

what sardonic kindness he permitted Peter Robinson’s company to go by

land.

The toils of this argonautic expedition,—consisting of some forty men of

the 41st Regiment and two hundred and sixty militia,—cannot be better

expressed than in the diary of William McCay, who was a volunteer in

Captain Hatt’s company, which had proceeded from the camp of Queenston

to join Brock’s little army. Hatt’s contingent had a merry wagon ride

from Queenston to Fort Erie, and from there had rowed to the mouth of

the Grand River. We take up McCay's narrative from this point until he

reached Fort Maiden.

“August 7th, 1812. We slept under the trees on the bank of the river,

arose early and set off. We did not land until we came to Patterson’s

Creek, about forty miles from the Grand River. Here we were informed

that the volunteers from York, some of the 41st Regiment and some

militia lay that were to go with us.

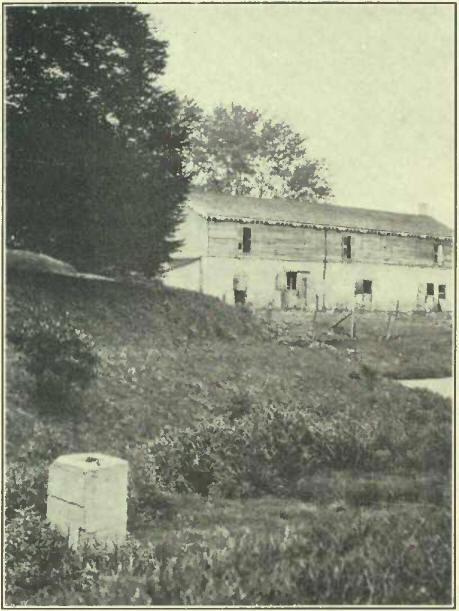

The Remains of Old Fort Malden. The Tree to the left is said to be the

finest Linden in America

“August 8th,

1812.—Slept on shore in the best manner we could.

Two of our company deserted this morning, James By craft and Harvey

Thorne. We did not leave this place until 12 o’clock, when we set off

and came to Long Point in the evening, drew our boats across and put up

for the night.

“August 9th, 1812.-—Arose early this morning and about sunrise were

joined by General Brock and six boat loads with troops from Patterson’s

Creek We all set off together, having a fair wind till about 1 o’clock,

and then rowed till night, when we landed at Kettle Creek, about six

miles below Port Talbot.

“August 10th, 1812.—Wet and cold last night; some of us lay in boats and

some on the sand. We set off early, but the wind blew so hard we were

obliged to put into Port Talbot. We covered our baggage from the rain,

which still continued, and most of us set out to get something to eat,

being tired of bread and pork. Five of us found our way to a place,

where we got a very good breakfast, bought some butter and sugar and

returned. Lay here all day, the wind being high.

“August 11th, 1812.—Set off early with a fair wind, but it soon blew so

hard we had to land on the beach and draw up our boats, having come

twelve or fifteen miles. Some of us built camps and covered them with

bark to shelter us from the rain, which poured down incessantly, but I

was obliged to go on guard, wet as I was. Some of our men discovered

horse tracks a few miles above us, which we supposed were American

horsemen, for we were informed they came within a few miles of Port

Talbot.

“August 12th, 1812. We set off before daylight and came on until

breakfast time, when we stopped at Point—where we found plenty of sand

cherries. They are just getting ripe and very good. We continued our

journey all night, which was very fatiguing, being so crowded in the

boats we could not lie down.

“August 13th, 1812.- We came to a settlement this morning, the first

since we left Port Talbot. The inhabitants informed us the Americans had

all retired to their own side of the river, also that there was a

skirmish between our troops and them on their own side, that is, the

American side, of the river. We made no stop, only to boil our pork, but

kept on until 2 o’clock, when we lay on the beach until morning. Some of

the boats with the General went on.

“August 14th, 1812.—We landed at Fort Maiden about 8 o’clock, very tired

with rowing, and our faces burned with the sun until the skin came off.

Malden is about two miles from the lake, up the river, in which there

are several small islands. The banks are low and well cultivated near

the river, but a wilderness back from it. Our company was marched to the

storehouse, where we took out our baggage and dried it and cleaned our

guns; Were paraded at 11 o’clock and all our arms and ammunition that

were damaged were replaced. We then rambled about the town until

evening, when all the troops that were in Amherstburg were paraded on

the commons. They were calculated at eight or nine hundred men.”

Two orders of General Block8 are of interest to students of what is now

appropriately called amphibious warfare and show that the General meant

to be in the forefront of the flotilla and that he had his anxieties.

Headquarters, Ranks of Lake Erie,

15 Miles S.W of Port Talbot,

August 11th, 1812, 0 o’clock, p.m.

General Orders:

The troops will hold themselves in readiness, and will embark in the

boats at twelve o’clock this night precisely.

It is Major General Brock’s positive order that none of the boats go

ahead of that in which is the Head Quarters, where a light will be

carried during the night.

The officers commanding the different boats will immediately inspect the

arms and ammunition of the men, and see that they are constantly kept in

a state for immediate service, as the troops are now to pass through a

part of the country, which is known to have been visited by the enemy’s

patroles.

A captain, with a subaltern and thirty men, will mount as picquet upon

the landing of the boats and a sentry will be furnished from each boat,

who must be regularly relieved to take charge of the boats and baggage,

etc.

A patrole from the picquet will be sent out on landing to the distance

of a mile from the encampment.

By order of the Major General.

J. B. Glegg, Capt. A.D.C.

J. Macdonell, P.A.D.C.

Point Aux Pins,

Lake Erie, August 12th, 1812.

General Orders:

It is Major General Brock’s intention should the wind continue fair, to

proceed during the night. Officers commanding boats will therefore pay

attention to the order of sailing as directed yesterday. The greatest

care and attention will be requested to prevent the boats from

scattering or falling behind.

A great part of the bank of the lake, which the boats will this day

pass, is much more dangerous and difficult of access than any we have

passed. The boats therefore will not land, excepting in the most extreme

necessity, and then great care must be taken to choose the best places

for landing.

The troops being now in the neighbourhood of the enemy, every precaution

must be taken to guard against surprise.

By order of the Major General,

J. B. Glegg, A.D.C.

That Brock knew what to do when a marine emergency arose is proved by

the fact that when his own boat ran hard aground, like the standard

bearer of Caesar’s Tenth Legion, he set the example by leaping into the

water. From which we can understand the meaning of Lieut. Robinson

(afterwards exalted to the rank of Chief Justice, when as late as 1840

he expressed a vivid remembrance of his general in the words: “It would

have required much more courage to refuse to follow General Brock than

to go with him wherever he would lead.”

Referring to his comrades in this campaign the same brilliant

soldier-judge has written:—“This body of men consisted of farmers,

mechanics and gentlemen, who before that time had not been accustomed to

any exposure unusual with persons of the same description in other

countries. They marched on foot and travelled in boats and vessels,

nearly six hundred miles in going and returning, in the hottest part of

the year, sleeping occasionally on the ground and frequently drenched

with rain, but not a man was left behind in consequence.” Perhaps their

best eulogy is in Brock’s own words: “Their conduct throughout excited

my admiration.”

The other events of this wonderful campaign, the going up to Sandwich,

the crossing of the Detroit with Brock standing in the bow of the

foremost boat, and the stupendous surrender of Hull’s army to a little

force of whom the Americans complained “four hundred were Canadian

militia disguised in red coats,” —are not these related in the

chronicles.

What much searching of history will further reveal is that the

indefatigable Peter Robinson and his Rifle Company of the 1st Yorks,

having reached Sandwich in time to share in all these glorious

operations, was given the honour of going aboard as body-guard to Brock

himself on a very small trading schooner; which after nearly running

aground at Buffalo was eventually towed into harbour at Port Erie. |