|

Crossing and re-crossing the

Continent.—Writers on the North-west.—Mineral wealth behind Lake

Superior.—The "Fertile-belt."—Our fellow travellers.—The "Rainbow"of the

North-west.—Peace River.—Climate compared with Ontario- —Natural riches of

the Country. — The Russia of America. — Its army of construction. — The

pioneers.—Esprit de corps. — Hardships and hazards. — Mournful death-roll.

— The work of construction —Vast breadth of the Dominion.—Its varied

features. — Its exhaustless resources.—Its constitution.—Its Queen.

The preceding chapters are

transcribed -almost verbally— from a Diary that was written from day to

day on our journey from Ocean, Ocean-ward. The Diary was kept under many

difficulties. Notes had to be taken, sometimes in the bottom of a canoe

and sometimes leaning against a stump or a tree; on horseback in fine

weather, under a cart when it was raining or when the sun's rays were

fierce; at night, in the tent, by the light of the camp-fire in front; in

a crowded wayside inn, or on the deck of a steamer in motion. And they

were written out in the first few weeks after our return, as it was

desirable,—if published at all—that they should be in the printer's hands

at once.

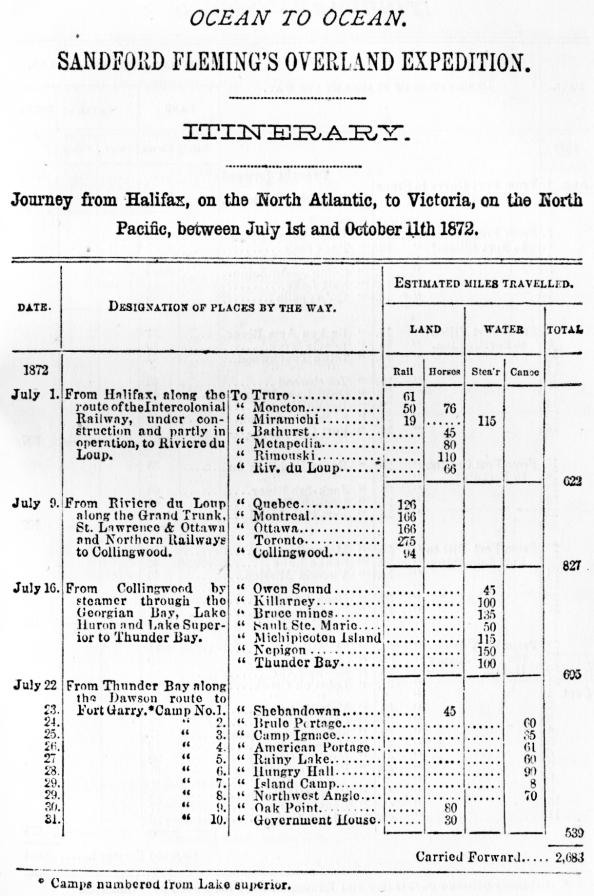

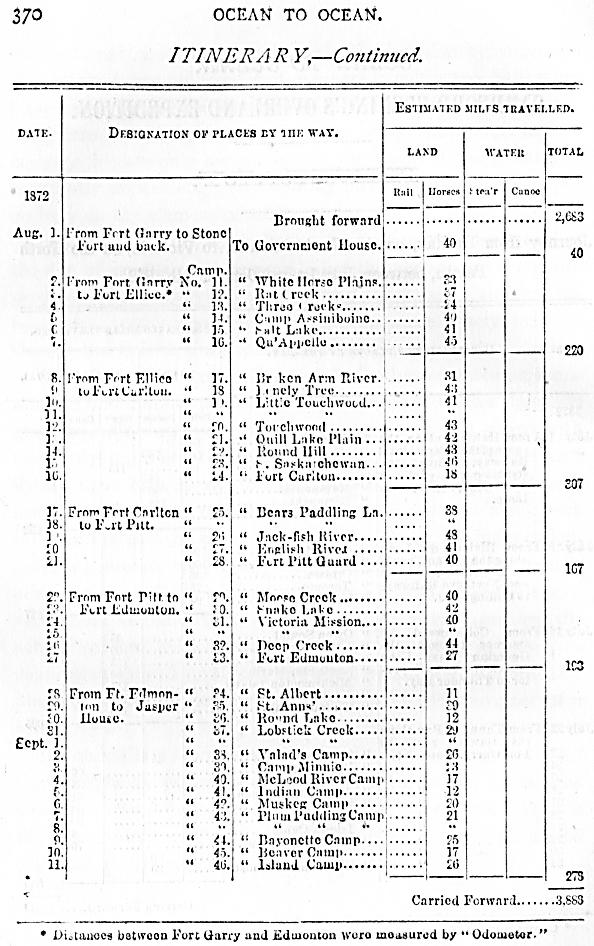

As may be seen by a

reference to the Itinerary in the Appendix, our Diary commenced at Halifax

on the Atlantic coast on July 1st the sixth anniversary of the birth-day

of the Dominion, and closed at Victoria on the Pacific coast on October

nth. The aggregate distance travelled by one mode of locomotion or another

was more than five thousand miles, a great part of it over comparatively

unknown, and therefore supposed to be dangerous country. We recrossed the

Continent to our starting point by rail, the Secretary arriving at Halifax

on November 2nd, having thus accomplished the round trip of nine or ten

thousand miles in four months. None of us sufferred from Indians, wild

beasts, the weather, or any of the hardships incidental to travel in a new

and lone land. Every one looked, and was, physically better on his return

than when he had Set out. And yet there had been no playing on the road.

We cannot charge ourselves with having lost an hour on the way; and

Manitobans, Hudson's Bay Officers, and British Columbians all informed us

that we made better time between Lake Superior and the Pacific than ever

had been made before in these latitudes.

It is only fair to the

public to add that the writer of the Diary knew little or nothing of our

North-west before accompanying the expedition. To find out something about

the real extent and resources of our Dominion; to know whether we had room

and verge for an Empire or were doomed to be merely a cluster of Atlantic

Provinces, ending to the west in a fertile but comparatively insignificant

peninsula in Lake Huron, was the object that attracted a busy man from his

ordinary work, on what friends called an absurd and perilous enterprise.

All that is claimed for the preceding chapters is, that they record

truthfully what we saw and heard. And having read since the works of

Professor Hind, Archbishop Taché, Captain Palliser and others, we find,

that though these contain the results of much more minute and extended

enquiries and scientific information which renders them permanently

valuable, they bring forward nothing to make us modify our own

conclusions, or to lessen the impression as to the value of our

North-west, that the sight of it produced in our own minds.

We are satisfied that the

rugged and hitherto unknown country extending from the upper Ottawa to the

Red River of the north, is not, as it has always been represented on maps

executed by our neighbours, and copied by ourselves, impracticable for a

Railway; but entirely the reverse; that those vast regions of Laurentian

and Huronian rocks once pronounced worthless, are rich in minerals beyond

conception, rich in gold, silver, copper, iron, tin, phosphates of lime,

and—strange as the assertion may appear—probably coal; that in the iron

back-ground to the basin of the St. Lawrence, hitherto considered valuable

only for its lumber, great centres of mining and manufacturing industry,

shall in the near future, spring into existence; and that for the

development of all this wealth, only the construction of a Railway is

necessary.

Beyond those apparently

wilderness regions we came upon the fertile belt, an immense tract of the

finest land in the world, bounded on the west by coal formations so

extensive that all other coal fields are small in comparison. Concerning

this central part of the Continent, we have testified that which we have

seen, and as a summary it is sufficient to quote Hind's emphatic words,

Vol. II, p. 234

"It is a physical reality

of the highest importance to the interests of

"British North America that a continuous belt, rich in water, woods and

''pasturage can be settled and cultivated from a few miles west of the

lake

"of the Woods, to the passes of the Rocky Mountains; and any line of

"communication, whether by waggon road or railroad, passing through it,

"will eventually enjoy the great advantage of being fed by an

agricultural

"population, from one extremity to the other."

Concerning the country from

the Mountains to the sea, it is unnecessary to add anything here. The

mountains in British Columbia certainly offer obstructions to Railway

construction; but these obstacles are not insuperable, and, once overcome,

we reach the Canadian Islands in the Pacific, Vancouver and Queen

Charlotte,—in many respects the counter parts of Great Britain and

Ireland, the western out posts of Europe,—our western islands are rich in

coal, bitumenous and anthracite, and almost every variety of mineral

wealth, in lumber, fish, and soil, and blessed with one of the most

delightful climates in the world.

And now we might take

farewell of the reader who has accompanied us on our long journey, but

before doing so, it seems not unfitting to add a few words concerning the

routes of our fellow-travellers who parted from us at Forts Garry and

Edmonton ; concerning those men whom we found engaged on the survey, and

the general impressions left on our minds by all that we saw and

experienced.

The Colonel spent ten days

in Manitoba inspecting the military force on duty at Fort Garry, the Stone

Fort and Pembina. Leaving Fort Garry, he travelled rapidly to Edmonton by

the same trail that we had taken, in the hope of overtaking us before we

had left for the mountains. Finding on his arrival that we had started

seven days previously, he wisely decided to proceed 145 miles south-west

to the Rocky Mountain House; thence, through the country of the Blackfeet,

to cross the mountains by North Kootenay Pass; and thence into Washington

Territory, U. S., and via. Olympia to Victoria. He accomplished the

journey successfully, though detained for two or three days by a

snow-storm at the foot of the mountains; but as the delay enabled him to

shoot a large grizzley bear that approached within a few yards of his

camp, he had no reason to regret it much. His southerly march from

Edmonton gave him the opportunity of seeing the western curve of the

fertile belt—"the rainbow of the North-west"—and he speaks of it,

especially of that portion through the Blackfeet country, extending for

about 300 miles along the eastern bases of the Rocky Mountains towards the

international boundary line, with a varying breadth of from 60 to 80

miles, as the future garden of the Dominion; magnificent in regard to

scenery, with soil of surpassing richness; and in respect of climate, with

an average temperature during the winter months, 15° higher than that of

the western portion of the Province of Ontario.

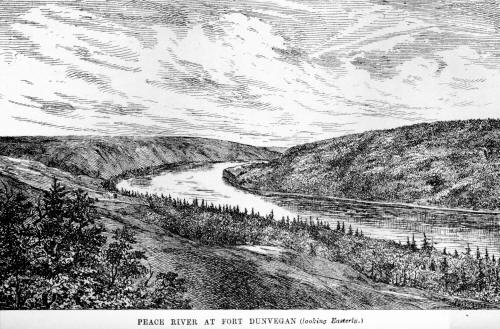

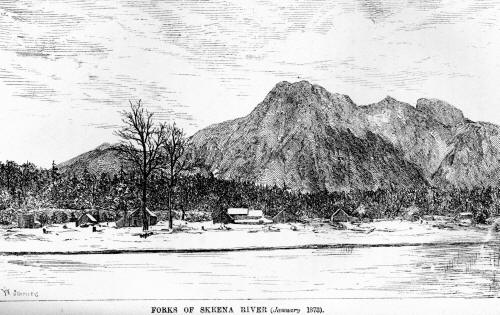

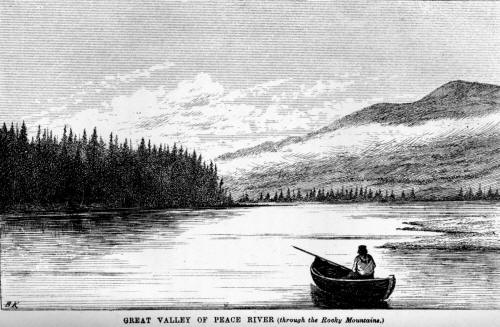

But we are now able to

speak concerning a northwestern curve of the fertile belt as positively as

of the district to the south which the Colonel traversed. At Edmonton, the

Chief sent the Botanist and Horetzky northwards, with instructions to

proceed by Forts Assiniboine and Dunvegan and across the Rocky Mountains

by Peace River, the one to make then for the Upper Fraser, and the other

to go still farther north and reach the sea by the Skeena or Nasse River.

They also succeeded in their journey; and their reports more than confirm

the statements of previous writers with regard to the extraordinary

fertility of immense prairies along the Peace River, the salubrity, and

the comparative mildness of the climate. It is quite clear that

exceptional climatic causes are at work along the eastern flank of the

Rocky Mountains, north as well as south of Edmonton. Whether the chief

cause be warm moist winds from the Pacific or a steady current of warm air

under the lee of the mountains, analogous in the atmosphere, to the Gulf

stream in the ocean, or whatever the cause, our knowledge is too imperfect

to enable us to say. But the great salient facts are undoubted. At Fort

Dunvegan, six degrees north of Fort Garry, and nearly thirteen north of

Toronto, the winters are milder than at Fort Garry; and as for the seven

months, from April to October, the period of cultivation, according to

tables that have been carefully compiled, Dunvegan and Toronto do not vary

more than about half a degree in mean temperature, while as compared with

Halifax N. S., the difference is 1° 69' in favour of Dunvegan. Our two

fellow-travellers assured us also that they had seen nothing between the

Red River and Edmonton to compare with the fertility of soil and the

beauty of the country about Peace River. They struck the mighty stream

below Dunvegan and sailed on it up into the very heart of the Rocky

Mountains, through a charming country, rich in soil, wood, water, and

coal, in salt that can be gathered fit for the table, from the sides of

springs with as much ease as sand from the sea-shore; in bitumenous

fountains into which Sir Alexander McKenzie and Harmon both say that "a

pole of twenty feet in length may be plunged, without the least

resistance, and without finding bottom," and in every other production

that is essential to the material prosperity of a country.

The following extract from

the Journal of our Botanist gives a graphic description of what Peace

River itself is;—

"This

"afternoon we passed through the most enchanting and sublime

"scenery. The right bank of the River was clothed with wood-

"spruce, birch and aspen, except where two steep, or where

"there had been landslides. In many places the bank rose

"from the shore to the height of from 300 to 600 feet. Sand-

"stone cliffs, 300 feet high, often showed, especially above

"Green Island. The left bank was as high as the right, but

"instead of wood, grassy slopes met the view; but landslides

"always revealed sandstone. In places, the river had cut a

"passage through the sandstone to the depth of 300 feet and

"yet the current indicated little increase. The river was full

"from bank to bank, was fully 600 yards wide, and looked

"like a mighty canal cut by giants through a mountain. Up

"this we sped at the rate of four miles an hour, against the

"current, in a large boat belonging to the Hudson's Bay Co'y.;

"propelled by a north-east gale."

When we remember that the

latitude of this river and the richest part of the country it waters is

nearly a thousand miles north of the Lake Ontario, the language we have

used about it may sound exaggerated because the facts seem unaccountable.

But the facts have been long on record. The only difficulty was the

inaccessibility of the country. In Harmons Journal are such entries as the

following:—

"Peace River, April 18,

1809.—

This morning the ice in the river broke up.

"April 30th is shown by the

public records, to be the mean time of opening of navigation at Ottawa,

between 1832 and 1870. Daring that period, 38 years, April 17th was the

earliest and May 29th the latest days of opening.

"May 6.—The surrounding

plains are all on fire. We have planted our potatoes, and sowed most of

our garden seeds."

"July 21.—We have cut down

our barley; and I think it is the finest that I ever saw in any country."

"October 6.—As the weather

begins to be cold, we have taken our vegetables out of the ground, which

we find to be very "productive."

Another year we have the

following entry:—

"October 3.—We have taken

our vegetables out of the ground. We have 41 bushels of potatoes, the

produce of one bushel "planted the last spring. Our turnips, barley, etc.,

have produced "well."

In the journal of a

Hudson's Bay Chief-factor published last year by Malcolm McLeod, Ottawa,

is the following extract concerning the climate of Dunvegan, from the

records of the celebrated traveller and astronomer—Mr. David Thompson:—

"Only twice in the month of

May 1803,—on the 2nd and 14th, did the thermometer fall to 30°. Frost did

not occur in the fall till the 27th September."

"It freezes," says Mr.

Russell, "much later in May in Canada; and at Montreal, for seven years

out of the last nine, the first " frost occurred between 24th August and

16th September."

In Halifax, N. S., the

writer has seen a lively snow-storm on the Queen's birth-day; and almost

every year there is frost early in June.

Similar quotations could be

given from other writers, but they are unnecessary. We know that we have a

great North-west, a country like old Canada—not suited for lotus-eaters to

live in, but fitted to rear a healthy and hardy race. The late Hon. W. H.

Seward understood this when he declared that "vigorous, perennial,

ever-growing Canada would be a Russia behind the United States." Our

future is grander than even that conceived by Mr. Seward, because the

elements that determine it are other than those considered by him. We

shall be more than an American Russia, because the separation from Great

Britain to which he invites us is not involved in our manifest destiny. We

believe that union is better than disunion, that loyalty is a better

guarantee for true growth than restlessness or rebellion, that building up

is worthier work than pulling down. The ties that bind us to the

Fatherland must be multiplied, the connection made closer and politically

complete. Her traditions, her forms, her moral elevation, her historic

grandeur shall be ours forever. And if we share her glory, we shall not

shrink even at the outset from sharing her responsibilities.

A great future beckons us

as a people onward. To reach it, God grant to us purity and faith,

deliverance from the lust of personal aggrandizement, unity, and

invincible steadfastness of purpose. The battles we have to fight are

those of peace, but they are not the less serious and they are surely

nobler than those of war. The victories we require to gain are over all

forms of political corruption, the selfish spirit of separation, and those

great material obstacles in the conquest of which the spirit of patriotism

is strengthened. It is a standing army of engineers, axemen and brawny

labourers that we require, men who will not only give "a fair day's work

for a fair day's wage," but whose work shall be ennobled by the thought

that they are in the service of their country and labouring for its

consolidation. Why should there not be a high esprit de corps among men

who are doing the country's work as well as among those who do its

warfare? And why should the country grudge its honours to servants on

whose faithfulness so much depends? "There is many a red-coat who is no

soldier," said the Duke of Wellington. Conversely, there are true soldiers

who wear only a red shirt.

This thought leads us to

make mention of the men who have been engaged for the last two years in

connection with the Canadian Pacific Railway Survey, the pioneers of the

great army that must be engaged on the construction of the work and on

whom has devolved the heavy labour that commonly falls to the lot of an

advance-guard. On our journey we met several of the surveying parties, and

could form some estimate of the work they had to do. We could see that

continuous labour for one or two years in solitary wilderness or mountain

gorges as surveyor, transit-man, leveller, rodman, commissary, or even

packer, is a totally different thing from taking a trip across the

continent for the first time, when the perpetual novelty, the spice of

romance, the risks and pleasures atone for all discomforts. Here are one

or two instances of the spirit that animates the body.

The gentleman now at the

head of party X had commenced work in charge of another party between Lake

Superior and the Upper Ottawa. He remained out during the whole summer and

winter in that trackless rugged region, previously untrodden by white men

and rarely visited by Indians. After a severe winter campaign, he

completed the difficult and hazardous service entrusted to him. On his

return in the spring, he was told that it was desirable that he should go

to British Columbia without delay; and, though he had not spent two weeks

with his family in as many years, he started at once.

Near the end of the year

just closed, the Chief was called upon to send a party to explore the

section of country between the North Saskatchewan, above Edmonton, and the

Jasper valley. It was deemed advisable to examine this wild and wooded

district in the winter season, on account of the numerous morasses and

muskegs which rendered it next to impassable at any other season. The

party most available for this service had been engaged during the summer

and winter of 1871 and the whole of 1872 in the lake region east of

Manitoba, and had returned to Fort Garry after completing satisfactorily

their arduous work. The Chief asked, by telegraph, the Engineer in charge

if he was prepared to start at short notice for the Rocky Mountains on a

prolonged service. Almost immediately after sending this message, the

following telegram was received from the gentleman referred to. " May I

have leave of absence to return home for a few weeks on urgent private

business ?" This was at once followed by another; "Your message received.

I withdraw my application for leave. I am prepared to start for the Rocky

Mountains with my party. Please send instructions." It was evident that

the first two telegrams had crossed. The members of party M,

notwithstanding what they had gone through, away from friends and the

comforts of society, were ready to undertake a march of a thousand miles

still farther away, in the dead of a Canadian winter.

And what was the journey?

They knew that it implied hardships such as Captain Butler encountered,

and which he so graphically describes in "The Great Lone Land." They knew

that it meant a great deal more. The journey over, they were only at the

beginning of their work, and the work would be infinitely more trying than

the journey itself.

These are only two

instances out of many of that 'Ready, aye Ready' spirit, which the British

people rightly honour as the highest quality in their soldiers, from the

lowest to the highest grades. With respect to the ordinary everyday work

that has to be done, our own little experience gave us some idea of its

discomforts. Among the mountains, there is hardly a day without rain,

except when it snows. Leather gives way under the alternate rotting and

grinding processes that swamps and rocks subject it to. Mocassins keep out

the wet about as well as an extra pair of socks. Clothes are patched and

re-patched until lock-stock-and-barrell are changed. At night you lie down

wet, lucky if the blanket is dry. In the morning you rise to a rough

breakfast of tea, pork and beans. When relations at home are just enjoying

the sweet half-hour's sleep before getting up, you are off into the dark

silent woods, or clambering up precipices to which the mists ever cling,

or on the rocky banks of some roaring river, the sound of which has become

positively hateful; getting back to camp at night tired and hungry, but

still thankful if a good day's work has been accomplished. And this same

thing goes on from week to week,—working, eating, sleeping. Books are

scarce for they are too bulky to carry; no newspapers and no news—unless

fragments from three to six months old, strangely metamorphosed by Packers

and Indians, can be dignified by the name of news. Nothing occurs to break

the monotony save rheumatism, festered hands or feet, or a touch of

sickness, perhaps scurvy if the campaign has been long : the arrival of a

pack-train with supplies, or some such interesting event as the following,

which we found duly chronicled on a blazed tree, between Moose Lake and

Tete Jaune Cache:—

"BIRTH,

"Monday, 5th August 1872.

"This morning at about 5

o'clock. 'Aunt Polly,' bell-mare to

"the Nth. Thompson-trail parties pack-train, was safely delivered

"of a Bay Colt, with three white legs and white star on forehead.

"This wonderful progeny of a C. P. R. Survey's pack-train, is

"in future to be known, to the racing community of the Pacific

"slope, as Rocky Mountain Ned."

The Sunday rest and the

next meal, are almost the only pleasures looked forward to; and the

enjoyment of eating arises, generally, not from the delicacies or variety

of the fare, but from the appetite brought to it; for luxuries, as we had

considered fat pork, porridge, good bread, and coffee, after three weeks

on pemmican, they need all the zest that hard work and mountain air can

supply, in order to be thoroughly enjoyed three times a day, week in and

week out.

In addition to all the—not

ordinary but—extraordinary discomforts attending this class of work there

are the dangers to life, inseparable from the great extent of the work

undertaken ; the rapidity with which it was begun and pushed forward;

extensives fires in the forest; drowning, while endeavouring to make the

passage of some lake or river in a frail canoe or on a raft; to say

nothing of starvation, which, notwithstanding the utmost care and

forethought, might, nay in some instances did very nearly, occur, in

consequence of accidents, like the two last named, befalling some of the

Commissariat department.

But this survey work

implies more than hardships and hazards. Already it has connected with its

history a mournful death-roll. At the outset, some tribes of Indians were

expected to give trouble. On the contrary, they have for the most part

been friendly and helpful. When nearly a thousand men were engaged

directly or indirectly on the work, and scattered over pathless regions

over a whole continent, it would not have been wonderful had supplies

failed to reach some parties, and death by starvation occurred. In no case

has such a disaster yet happened. But there are forces that can neither be

organized nor bribed. Fourteen men have been destroyed by the elements;

seven by fire, and seven by water; destroyed so completely that no trace

has been found of the bodies of ten.

One party,—seven in

number,—engaged in carrying provisions north of Lake Superior, was

surprised by the wide-spread forest fires that raged over the west in the

autumn of 1871. The body of only one of its number could be discovered.

In the spring of 1872, a

party that had finished its work well, after an arduous winter campaign

far up the Ottawa beyond Lake Temiscamang, prepared to return home. The

gentleman in charge and one of his assistants separated from the rest, to

take on board their canoe two others who had been previously left at a

side post prostrated with scurvy. The four were known to have then started

down the river. That was the last seen of them, though the upturned canoe

was found, and it told its own tale of an upset by rock or rapid or

awkward movement of the sick men into ice-cold lake or river.

In the autumn of 1872,

three others, on their way to begin their winter's work, were shipwrecked

and drowned in the Georgian Bay.

All those men died in the

service of their country as truly as if they had been killed in battle.

Some of them have left behind wives and little children, aged parents,

young brothers or sisters, who were dependent on them for support. Have

not those a claim on the country that ought not to be disregarded?

That this work is too

seldom looked at from any other save the "wages" point of view, is our

excuse for putting the real state of the case warmly. Who are the men

whose disciplined enthusiasm enables them to manifest the self-sacrifice

we have alluded to? Many of them are men of good birth and education, who

have chosen the profession of Engineering as one in which their talents

can be made in a marked degree subservient to the material prosperity of

mankind. Others have chosen it because of its supposed freedom from

routine, and the prospect it is thought to offer of novelty, adventure,

and such a roving life as every young Briton or Canadian, with any of the

old blood in his veins, longs for.

And what 'wages' do these

men, who deserve so well of their country, receive? Simply their pay by

the month! They do not know whether they will have the satisfaction—that

every man interested in his work has the right to look forward to—of

seeing their work finished by themselves. Even after the preliminary

surveys are completed, and the work placed under contract, the tenure of

office is insecure. Sometimes a clamour is raised, against the presumed

extravagance of the Government, when the newspapers have nothing more

stirring to write about, or when some reporter fancies he has not received

due attention. At other times, some unfeeling and unprincipled contractors

conspire to effect the removal of men, whose only fault is that they have

performed their duty faithfully. From these or other similar causes,

engineers in the public service are sometimes most unjustly sacrificed.

And, if remonstrance is made, the answer is ready.—'They received their

pay for the time they were employed, and others, quite as competent, are

ready and willing to take their places.'—Yes, and the same might be said

of the officers and men of the British army, but they are treated very

differently. The work performed on one of the military expeditions, such

as the Abyssinian or Red River, about which so much has been written, and

which are said to have shed such lustre on the British name, is really not

more arduous than theirs The heaviest part of a soldier's duty on such

expeditions it is well known is the long laborious marching. The work of

engineers on the survey is a constant march ; their shelter, even in the

depth of winter, often only canvas; they have sometimes to carry their

food for long distances, through swamps and over fallen trees, on their

backs; and run all the risks incidental to such a life, without medical

assistance, without notice from the press, without the prospect of plunder

or promotion, ribands or pensions. To be sure theirs is the work of

construction only, and the world has always given greater prominence to

the work of destruction.

To construct is "the duty

that lies nearest us." "We therefore will rise up and build." Our young

Dominion in grappling with so great a work has resolutely considered it

from a national and not a strictly financial point of view; knowing that

whether it 'pays' directly or not, it is sure to pay indirectly. Other

young countries have had to spend, through long years, their strength and

substance to purchase freedom or the right to exist. Our lot is a happier

one. Protected "against infection and the hand of war" by the might of

Britain, we have but to go forward, to open up for our children and the

world what God has given into our possession, bind it together,

consolidate it, and lay the foundations of an enduring future.

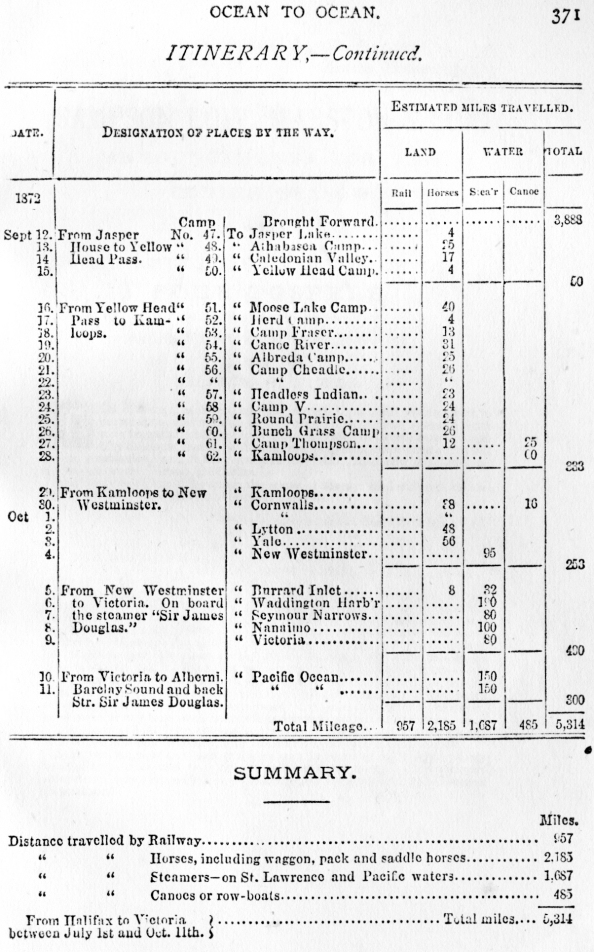

Looking back over the vast

breadth of the Dominion when our journeyings were ended, it rolled out

before us like a panorama, varied and magnificent enough to stir the

dullest spirit into patriotic emotion. For nearly 1,000 miles by railway

between different points east of Lake Huron; 2,185 miles by horses,

including coaches, waggons, pack, and saddle-horses; 1,687 miles in

steamers in the basin of the St. Lawrence and on Pacific waters. and 485

miles in canoes or row-boats; we had travelled in all 5,300 miles between

Halifax and Victoria, over a country with features and resources more

varied than even our modes of locomotion.

From the sea-pastures and

coal-fields of Nova Scotia and the forests of New Brunswick, almost from

historic Louisburg up the St. Lawrence to historic Quebec; through the

great Province of Ontario, and on lakes that are really seas; by copper

and silver mines so rich as to recall stories of the Arabian Nights,

though only the rim of the land has been explored; on the chain of lakes,

where the Ojibbeway is at home in his canoe, to the great plains, where

the Cree is equally at home on his horse; through the prairie Province of

Manitoba, and rolling meadows and park-like country, equally fertile, out

of which a dozen Manitobas shall be carved in the next quarter of a

century; along the banks of

A full-fed river winding

slow

By herds upon an endless plain,

full-fed from the

exhaustless glaciers of the Rocky Mountains, and watering 'the great lone

land;' over illimitable coal measures and deep woods; on to the mountains,

which open their gates, more widely than to our wealthier neighbours, to

lead us to the Pacific ; down deep gorges filled with mighty timber, and

rivers whose ancient deposits are gold beds, sands like those of Pactolus

and channels choked with fish ; on to the many harbours of mainland and

island, that look right across to the old Eastern Thule 'with its rosy

pearls and golden-roofed palaces,' and open their arms to welcome the

swarming millions of Cathay; over all this we had travelled, and it was

all our own.

"Where's the coward that

would not dare

To fight for such a land?"

Thank God, we have a

country. It is not our poverty of land, or sea, of wood or mine that shall

ever urge us to be traitors. But the destiny of a country depends not on

its material resources. It depends on the character of its people. Here,

too, is full ground for confidence. We in everything "are sprung, of

earth's first blood, have titles manifold." We come of a race that never

counted the number of its foes, nor the number of its friends, when

freedom, loyalty, or God was concerned.

Two courses are possible,

though it is almost an insult to say there are two, for the one requires

us to be false to our traditions and history, to our future, and to

ourselves. A third course has been hinted at; but only dreamers or

emasculated intellects would seriously propose "Independence" to four

millions of people, face to face with thirty-eight millions. Some one may

have even a fourth to propose. The Abbe Sieyes had a cabinet filled with

pigeon-holes, in each of which was a cut-and-dried Constitution for

France. Doctrinaires fancy that at any time they can say, 'go to, let us

make a Constitution,' and that they can fit it on a nation as readily as

new coats on their backs. There never was a profounder mistake. A nation

grows, and its Constitution must grow with it. The nation cannot be pulled

up by the roots,—cannot be dissociated from its past, without danger to

its highest interests. Loyalty is essential to its fulfilment of a

distinctive mission,—essential to its true glory. Only one course

therefore is possible for us, consistent with the self-respect that alone

gains the respect of others; to seek, in the consolidation of the Empire,

a common Imperial citizenship, with common responsibilities, and a common

inheritance.

With childish impatience

and intolerance of thought on the subject, we are sometimes told that a

Republican form of Government and Republican institutions, are the same as

our own. But they are not ours. Besides, they are not the same in

themselves; they are not the same in their effects on character. And, as

we are the children even more than we are the fathers and framers of our

national institutions, our first duty is to hold fast these political

forms, the influences of which on national character have been proved by

the tests of time and comparison to be the most ennobling. Republicanism

is one-sided. Despotism is other-sided. The true form should combine and

harmonize both sides.

The favourite principle of

Robertson, of Brighton, that the whole truth in the realm of the moral and

spiritual consists in the union of two truths that are contrary but not

contradictory, applies also to the social and political. What two contrary

truths then lie at the basis of a complete National Constitution?

First, that the will of the

people is the will of God. Secondly, that the will of God must be the will

of the people. That the people are the ultimate fountain of all power is

one truth. That Government is of God, and should be strong, stable, and

above the people is another. In other words, the elements of liberty and

of authority should both be represented. A republic is professedly based

only on the first. In consequence, all popular appeals are made to that

which is lowest in our nature, for such appeals are made to the greatest

number and are most likely to be immediately successful. The character of

public men and the national character deteriorate. Neither dignity,

elevation of sentiment, nor refinement of manners is cultivated. Still

more fatal consequences, the very ark of the nation is carried

periodically into heady fights ; for the time being, the citizen has no

country; he has only his party, and the unity of the country is constantly

imperilled. On the other hand, a despotism is based entirely on the

element of authority.

To unite those elements, in

due proportions, has been and is the aim of every true statesman. Let the

history of liberty and progress, of the development of human character to

all its rightful issues, testify where they have been more wisely blended

than in the British Constitution.

We have a fixed centre of

authority and government, a fountain of honour above us that all

reverence, from which a thousand gracious influences come down to every

rank; and, along with that fixity, representative institutions, so elastic

that they respond within their own sphere to every breath of popular

sentiment, instead of a cast-iron yoke for four years. In harmony with

this central part of our constitution, we have an independent judiciary

instead of judges—too often the creatures of wealth, adventurers on the

mere echoes of passing popular sentiment.— And, more valuable than even

the direct advantages, are the subtle, indirect influences that flow from

our living in unbroken connection with the old land, and the dynamical if

imponderable forces that determine the tone and mould the character of a

people.

"In our halls is hung

armoury of the invincible knights of old." Ours' are the old history, the

misty past, the graves of forefathers. Ours the names 'to which a thousand

memories call.' Ours is the flag; ours the Queen whose virtues transmute

the sacred principle of loyalty into a personal affection.

|