|

“Frank,” began he, “has called his a ‘bird-adventure.’ I

might give mine somewhat of the same title, for there was a bird mixed

up with it—the noblest of all birds—the eagle. But you shall hear it.

“On leaving the camp, I went, as you all know, up the

valley. After travelling for a quarter of a mile or so, I came upon a

wide open bottom, where there were some scattered willows and clumps of

dwarf birch-trees. As Luce had told me that such are the favourite food

of the American hare, or, as we call it in Louisiana, ‘rabbit,’ I looked

out for the sign of one, and, sure enough, I soon came upon a track,

which I knew to be that of ‘puss.’ It was fresh enough, and I followed

it. It kept me meandering about for a long while, till at last I saw

that it took a straight course for some thick brushwood, with two or

three low birches growing out of it. As I made sure of finding the game

there, I crept forward very quietly, holding Marengo in the leash. But

the hare was not in the brush; and, after tramping all through it, I

again noticed the track where she had gone out on the opposite side. I

was about starting forth to follow it, when all at once an odd-looking

creature made its appearance right before me. It was that fellow there!”

And Basil pointed to the lynx. “I thought at first sight,” continued he,

“it was our Louisiana wild-cat or bay lynx, as Luce calls it, for it is

very like our cat; but I saw it was nearly twice as big, and more

greyish in the fur. Well, when I first sighted the creature, it was

about an hundred yards off. It hadn’t seen me, though, for it was not

running away, but skulking along slowly—nearly crosswise to the course

of the hare’s track—and looking in a different direction to that in

which I was. I was well screened behind the bushes, and that, no doubt,

prevented it from noticing me. At first I thought of running forward,

and setting Marengo after it. Then I determined on staying where I was,

and watching it a while. Perhaps it may come to a stop, reflected I, and

let me creep within shot. I remained, therefore, crouching among the

bushes, and kept the dog at my feet.

“As I continued to watch the cat, I saw that, instead of

following a straight line, it was moving in a circle!

“The diameter of this circle was not over an hundred

yards; and in a very short while the animal had got once round the

circumference, and came back to where I had first seen it. It did not

stop there, but continued on, though not in its old tracks. It still

walked in a circle, but a much smaller one than before. Both, however,

had a common centre; and, as I noticed that the animal kept its eyes

constantly turned towards the centre, I felt satisfied that in that

place would be found the cause of its strange manoeuvring. I looked to

the centre. At first I could see nothing—at least nothing that might be

supposed to attract the cat. There was a very small bush of willows, but

they were thin. I could see distinctly through them, and there was no

creature there, either in the bush or around it. The snow lay white up

to the roots of the willows, and I thought that a mouse could hardly

have found shelter among them, without my seeing it from where I stood.

Still I could not explain the odd actions of the lynx, upon any other

principle than that it was in the pursuit of game; and I looked again,

and carefully examined every inch of the ground as my eyes passed over

it. This time I discovered what the animal was after. Close in to the

willows appeared two little parallel streaks of a dark colour, just

rising above the surface of the snow. I should not have noticed them had

there not been two of them, and these slanting in the same direction.

They had caught my eyes before, but I had taken them for the points of

broken willows. I now saw that they were the ears of some animal, and I

thought that once or twice they moved slightly while I was regarding

them. After looking at them steadily for a time, I made out the shape of

a little head underneath. It was white, but there was a round dark spot

in the middle, which I knew to be an eye. There was no body to be seen.

That was under the snow, but it was plain enough that what I saw was the

head of a hare. At first I supposed it to be a Polar hare—such as we had

just killed—but the tracks I had followed were not those of the Polar

hare. Then I remembered that the ‘rabbit’ of the United States also

turns white in the winter of the Northern regions. This, then, must be

the American rabbit, thought I.

“Of course my reflections did not occupy all the time I

have taken in describing them. Only a moment or so. All the while the

lynx was moving round and round the circle, but still getting nearer to

the hare that appeared eagerly to watch it. I remembered how Norman had

manoeuvred to get within shot of the Polar hare; and I now saw the very

same ruse being practised by a dumb creature, that is supposed to have

no other guide than instinct. But I had seen the ‘bay lynx’ of Louisiana

do some ‘dodges’ as cunning as that,—such as claying his feet to make

the hounds lose the scent, and, after running backwards and forwards

upon a fallen log, leap into the tops of trees, and get off in that way.

Believing that his Northern cousin was just as artful as himself,” (here

Basil looked significantly at the “Captain,”) “I did not so much wonder

at the performance I now witnessed. Nevertheless, I felt a great

curiosity to see it out. But for this curiosity I could have shot the

lynx every time he passed me on the nearer edge of the circle. Round and

round he went, then, until he was not twenty feet from the hare, that,

strange to say, seemed to regard this the worst of her enemies more with

wonder than fear. The lynx at length stopped suddenly, brought his four

feet close together, arched his back like an angry cat, and then with

one immense bound, sprang forward upon his victim. The hare had only

time to leap out of her form, and the second spring of the lynx brought

him right upon the top of her. I could hear the child-like scream which

the American rabbit always utters when thus seized; but the cloud of

snow-spray raised above the spot prevented me for a while from seeing

either lynx or hare. The scream was stifled in a moment, and when the

snow-spray cleared off, I saw that the lynx held the hare under his

paws, and that ‘puss’ was quite dead.

“I was considering how I might best steal up within

shooting distance, when, all at once, I heard another scream of a very

different sort. At the same time a dark shadow passed over the snow. I

looked up, and there, within fifty yards of the ground, a great big bird

was wheeling about. I knew it to be an eagle from its shape; and at

first I fancied it was a young one of the white-headed kind—for, as you

are aware, these do not have either the white head or tail until they

are several years old. Its immense size, however, showed that it could

not be one of these. It must be the great ‘golden’ eagle of the Rocky

Mountains, thought I.

“When

I first noticed it, I fancied that it had been after the rabbit; and,

seeing the latter pounced upon by another preying creature, had uttered

its scream at being thus disappointed of its prey. I expected,

therefore, to see it fly off. To my astonishment it broke suddenly out

of the circles in which it had been so gracefully wheeling, and, with

another scream wilder than before, darted down towards the lynx! “When

I first noticed it, I fancied that it had been after the rabbit; and,

seeing the latter pounced upon by another preying creature, had uttered

its scream at being thus disappointed of its prey. I expected,

therefore, to see it fly off. To my astonishment it broke suddenly out

of the circles in which it had been so gracefully wheeling, and, with

another scream wilder than before, darted down towards the lynx!

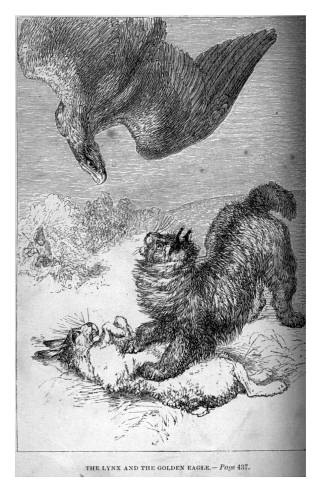

“The latter, on hearing the first cry of the eagle, had

started, dropped his prey, and looked up. In the eagle he evidently

recognised an antagonist, for his back suddenly became arched, his fur

bristled up, his short tail moved quickly from side to side, and he

stood with glaring eyes, and claws ready to receive the attack.

“As the eagle came down, its legs and claws were thrown

forward, and I could then tell it was not a bald eagle, nor the great

‘Washington eagle,’ nor yet a fishing eagle of any sort, which both of

these are. The fishing eagles, as Lucien had told me, have always naked

legs, while those of the true eagles are more feathered. So were his,

but beyond the feathers I could see his great curved talons, as he

struck forward at the lynx. He evidently touched and wounded the animal,

but the wound only served to make it more angry; and I could hear it

purring and spitting like a tom-cat, only far louder. The eagle again

mounted back into the air, but soon wheeled round and shot down a second

time. This time the lynx sprang forward to meet it, and I could hear the

concussion of their bodies as they came together. I think the eagle must

have been crippled, so that it could not fly up again, for the fight

from that time was carried on upon the ground. The lynx seemed anxious

to grasp some part of his antagonist’s body—and at times I thought he

had succeeded—but then he was beaten off again by the bird, that fought

furiously with wings, beak, and talons. The lynx now appeared to be the

attacking party, as I saw him repeatedly spring forward at the eagle,

while the latter always received him upon its claws, lying with its back

upon the snow. Both fur and feathers flew in every direction, and

sometimes the combatants were so covered with the snow-spray that I

could see neither of them.

“I watched the conflict for several minutes, until it

occurred to me, that my best time to get near enough for a shot was just

while they were in the thick of it, and not likely to heed me. I

therefore moved silently out of the bushes; and, keeping Marengo in the

string, crept forward. I had but the one bullet to give them, and with

that I could not shoot both; but I knew that the quadruped was eatable,

and, as I was not sure about the bird, I very easily made choice, and

shot the lynx. To my surprise the eagle did not fly off, and I now saw

that one of its wings was disabled! He was still strong enough, however,

to scratch Marengo severely before the latter could master him. As to

the lynx, he had been roughly handled. His skin was torn in several

places, and one of his eyes, as you see, regularly ‘gouged out.’”

Here Basil ended his narration; and after an interval,

during which some fresh wood was chopped and thrown upon the fire,

Norman, in turn, commenced relating what had befallen him. |