|

AT Edmonton we heard an

epidemic was raging among the southern Indians, and that many were dying. As

to the nature of the disease or particulars concerning it we had no

information. But even the rumor of its approach was startling, for in the

absence of any Government or other quarantine regulations and with tribal

war existing this disease would soon cover the whole country with its

ravages. In the meantime, as the season was advancing, we redoubled our

efforts to bring in supplies. To do this we had to travel largely at night,

the March sun making it too warm for our dogs in the daytime. This

night-work with the strong glare of the bright snow was exceedingly hard on

the eyes. Many a poor fellow became snow-blind, and the pain of this was

excruciating. Fortunately for myself, my eyes were never affected; but it

made me feel miserable to witness so much suffering and be helpless to give

relief.

The Indians as a preventive

would blacken their faces with charcoal or damped powder, but as nearly all

the natives had dark eyes, they were most susceptible to snow-blindness. My

experience was that those with lighter colored eyes were generally free from

this dreaded malady.

Old Joseph, Susa and myself

made a number of quick trips to and from different camps during these March

days and nights; and about the end of the month we gave this up for the

season. Then it came to pass that I put into execution a project I had been

contemplating for some time and that was to take unto me a wife. My bride to

be was the daughter of the Rev. H. B. Steinhauer. I had met her in the

autumn of 1862, when I accompanied father on his first visit to Whitefish

Lake. Our acquaintance, which had grown into a courtship on my part, was now

between two and three years old. Our parents willingly gave us their consent

and blessing. Father and Peter accompanied us to Whitefish Lake, and father

married us in the presence of my wife's parents and people. Our "honeymoon

trip" was to drive from Whitefish Lake to Victoria with dog-train, when the

season was breaking up, and in consequence the trip was a hard one. Then

after a short sojourn at Victoria we set out for the purpose of establishing

the new Mission at Pigeon Lake, father having signified his strong desire

that such should be done, notwithstanding that the Board of Missions had not

as yet either consented to or approved of such a course. But father was

thoroughly impressed with the wisdom and necessity of such action, and

finally told me I ought to go and begin work out there; and, said he, "You

can live where any man can." Of course I was proud to have father think this

of me. His knowledge of the work required, and his confidence in my ability

to do this work, more than made up to me at the time for the fact that there

was not a dollar of appropriation from the Missionary Society. But father

gave us a pair of four-point Hudson's Bay blankets, two hundred ball and

powder, and some net twine, together with his confidence and blessing; to

which in all things mother said, "Amen."

In the meantime the epidemic

we had heard rumors of came to us, and proved to be a dangerous combination

of measles and scarlet fever. Among the Black feet and the southern tribes

hundreds had died, and already the mortality was large among the northern

Crees. From camp to camp the disease spread. As winter still lingered and

the deep snow was again turning into water on the plains and in the woods,

these lawless, roving people without quarantine protection, lacking the

means of keeping dry or warm, and altogether destitute of medicine or

medical help, became an easy prey to the epidemic.

Already many lodges of sick

folk were camped close to the Mission, and others were coming in every day.

Father and mother and Peter had their hands full in attending to the sick,

ministering to the dying, and burying the dead. And as this was a white

man's disease, there were plenty of the wilder Indians to magnify the wrongs

these Indians were submitting to at the hands of the whites. Some of them

were exceedingly impudent and ugly to deal with; indeed, if it were not for

Maskepetoon and his own people, many a time our Mission party would have

suffered. As it was life was constantly in danger. Men and women crazed and

frenzied because of disease and death were beside us night and day.

Nevertheless father said "Go," and we started from among such scenes on our

journey to Pigeon Lake.

Father had loaned us two oxen

and carts for the trip. I had some eight or ten ponies, about all I had to

show for five years' work; but as I had been helpful to father in educating

my brother and sister in Ontario, I was thankful I had come off as well as I

did. A great part of the way was under water. The streams were full, but on

we rode and rolled and rafted and forded.

Our party consisted of my

wife and self, Oliver, a young Indian, Paul by name, and his wife. Our

provisions were buffalo meat, fresh and dry and in pemmican. We had five

bushels of potatoes with us, but these were saved for the purpose of

starting the new Mission. I purposed having every Indian who might come to

me begin a garden, and these potatoes were for seed, and should not be

eaten. Paul and I supplemented our larders by hunting. Ducks and geese,

chickens and rabbits saved the dried provisions and proved very good fare.

We scouted carefully across

and past those paths and roads converging from the plains and south country

to Fort Edmonton. Not until we had made sure, so far as we could, that the

enemy was not just then in the vicinity, did we venture our party across

these highways of the lawless tribes. Then passing Edmonton we struck out

south-westward, into a country wherein as yet no carts or waggons had ever

rolled; and now it kept Paul and myself busy hunting and clearing the way,

while Oliver and the women brought up the carts and loose horses. Our

progress was slow and tedious, but we were working for the future as well as

the present.

When up here in the winter I

concluded that we could on the first trip with carts take them to within

some twenty-live miles of the lake to which we were going. Working along as

best N%,6 could, Saturday night found us at this limit, and as we were very

tired, and the weather was fine, we merely covered our earth, made an open

fire in front, and thus prepared to spend the Sabbath in rest and quiet.

Because of the dense forest and brush we had come through, and also as we

were some thirty miles from Edmonton, we felt comparatively safe from any

war parties of plain Indians that might be roaming the country, as these men

were more or less afraid of the woods. Sunday was a beautiful day, but

towards evening there came a change, and during the night a furious

snowstorm set in. Monday morning there was nearly a loot of snow, and the

storm continued all. day and on into Tuesday night. We kept as quiet as

possible under our humble shelter without fire or any warm food until

Wednesday morning, when the sun came out and the storm was over. Then to our

dismay Mrs. McDougall and Paul's wife were taken with the measles, and

sending Oliver to look after the stock, Paul and I sought the highest ground

in the vicinity, cleared away the snow, cut poles and put up our leather

lodge.

This we floored thickly with

brush. Then we laid a brush causeway from our carts to the lodge, and moved

our sick folk into the tent. In the meantime I had put some dried meat and

pounded barley into a kettle to boil over the fire, and as the only medicine

we had was cayenne pepper, I put some of this into the soup, and this was

all we had for our sick ones. Just then Oliver came in, having found the

stock, but was complaining of a sore back and headache. I gave him a cup of

my hot soup to drink, and as he sat beside the fire warming his wet feet and

limbs and drinking the soup, I saw he was covered with the measles. So I

quietly told him to change his clothes and go into the tent. Thus in our

small party of five three were down with the epidemic which was now

universal in the North-West.

For the next five or six days

Paul and I had our hands full to attend to the sick night and day, to keep

up the supply of firewood (for the nights were cold and we consumed a great

amount) and to look after the stock.

Our patients in the

one-roomed buffalo-skinwalled hospital were very sick, and as we had no

medicine to speak of, and nothing in the way of dainties to tempt their

appetite, often caused us extreme anxiety. Hard grease pemmican, dried meat,

or pounded meat and grease are all right when one is strong and well, but it

was more than we could do to cook or fix these up for sick folk. When we

could Paul and I took it in turn to seek for ducks ad chickens to make broth

with, but there were very few of these to be found near to us, and it was

not until the fever abated that, by leaving wood and water ready and making

our patients as comfortable as possible, we went farther afield for game,

and were successful in finding ducks and geese and the eggs of wild-fowl as

our reward.

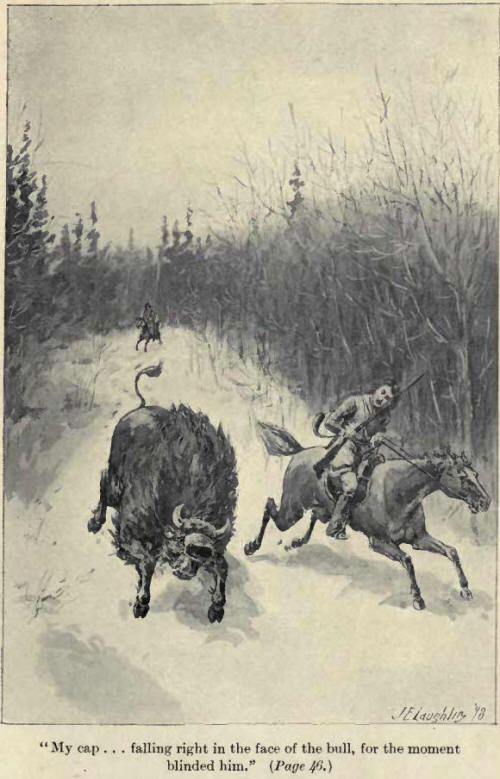

It was on one of these hunts,

and while our sick people were steadily convalescing, that we came upon the

fresh tracks of a buffalo bull. As we thought he might provide good meat we

determined to follow him up. I think we had kept his track steadily for

three hours, when all of a sudden my sleigh dogs, whom I had left as I

thought secure at camp, came up to us on the jump, and now took the lead on

the track, and very soon were at the bull, as we knew from their furious

barking. We rode as fast as we could in the soft ground and through the

dense bush, and presently galloped out on an old beaver- meadow. Sure enough

the dogs had the bull at bay, and the old fellow as soon as we came in sight

charged straight at us. As there was an opening into another part of the

meadow I thought he was making for that, so sat my horse, gun in hand, ready

to shoot him as he passed. But this was not in the bull's programme. lie was

in for a fight, and putting down his head came right at me. My horse knew

what that meant, for he already had been gored by a mad bull, and the little

fellow did not wait for a second dose, but bounded on as fast as he could.

My gun was a single-barrelled, muzzle-loading shot-gun, and though I had a

ball in, I did not care to risk my one shot under such circumstances. In

fact I very soon had all I could do to sit on my horse, keep my gun, and

save my head from being broken; for in a few bounds we were across the

meadow and into the woods, where, the ground being soft, my horse was hard

pressed by the big fellow, who was crashing along at his heels. Fortunately

"Scarred Thigh," as the Indians called him, was no ordinary cayuse, but

strong and quite speedy. Yet owing to soft ground and brush the bull seemed

to be gaining on us at several times. Paul afterwards told me he was so

close to me as to raise my pony's tail with his horn, but could not come

nearer to his much desired victims.

I knew that my horse could

not, sinking as he was at every jump into the soft ground, keep this gait up

much longer, and because of the trees and brush I had no chance to shoot

back at the bull. I was momentarily expecting to feel him hoisting us, when

I spied a thick cluster of big poplars just ahead. Now, I thought, if we can

dodge behind these we may gain time on our enemy. So I urged on my noble

beast, and as if to help us, just as I pulled him around the clump of

poplars, a projecting limb knocked my cap off'. This falling right in the

face of the bull for the moment blinded him, and with an angry snort he went

thundering past as I pulled behind the trees.

"That was close," said Paul,

who was following up as fast as his pony would bring him; 'if 'he had been a

bear he would have bitten your horse, but every time he put his head down to

toss you, your horse left him that much." I jumped from my horse and patted

his neck, rubbed his nose, and felt thankful for our escape. Then we tied

our animals in the shelter of the large trees, and followed after the bull

on foot, for in such ground and such timber we were much safer on foot than

on horseback.

Already our dogs had again

brought the bull to bay, as we could hear, and approaching with caution we

soon saw him fighting desperately. Alert as we were he heard us coining and

again charged, but we met him with two balls, and the old fellow staggered

back to the middle of a swamp of ice and snow-water and fell dead.

"That fellow had a bad heart,

or he would not have gone out into the middle of a pond of water to die,"

said Paul; and it was cold enough work skinning and butchering him, with the

ice-water up to our knees. But those were the days when stockings and boots

and rubbers were beyond our reach in more ways than one. However, the meat

was good and a providential supply to us and our sick folk. Moreover, our

dogs needed an extra feed, and they got it

It was late in the day when

two heavily laden horses and two tired men came in sight of camp, and it was

as good medicine to Oliver, who saw us approaching and noted the fresh meat

with a smile all over his gaunt and pale face, for the disease had wofully

thinned the poor fellow. Only those who have been in such circumstances can

truly appreciate the relief experienced by our sorely-tried party. |