|

Although the Dominion

of Canada is being meshed from coast to coast' in a network of steel,

the day when the iron horso will supersede all other means of locomotion

and transportation still remains very far distant. The country is full

of such startling surprises. So long as tempting prize-packets in the

form of new and richly fertile tracts of farming land, or mountain

slopes rich in minerals, arc* to be picked up by the hardy pioneers and

frontiersmen, so long will the wilds exercise their unfathomable

fascination and irresistible call.

The frontiersman in the

teeming city is like the Eskimo in the tropics. The song of civilisation

is a. nightmare; there is an absence of that “roughing it” in which he

revels: while the chances of making a “strike,” according to his

peculiar interpretation, are very frail. He cannot stifle the longing

for the droning music of the virgin forest, the solitude of the

wilderness, the difficulties of the trail; and the desire to assist in

the uplifting of the country in the interests of commerce and industry.

That is the reason why,

from time to time, the discovery of some new natural resources of groat

value sends a throb of excited interest vibrating round the world.

Ninety-nine times out of one hundred the new lode-stone in one of the

most out-of-the-way corners of the country, difficult of access, and

entailing terrible privations and daubers innumerable in the attempt to

gain it. The dogged determination and perseverance cf the pioneering

nomad revealed the agricultural possibilities of the Peace River

country, the golden treasure-chest of the Yukon, the minerals of

Northern Ontario, the wondrous Clay Belt the fertile Nechaco and Bulkley

Valleys, and so on.

When the news of the

frontiersman’s newly-found treasure-trove trickles out, then there is a

wild stampede from all quarters to the new hub of excitement. Everyone

is fired by that ambition—to be in on the “ground floor.” The

speculation fever grips the victim so malignantly that he never pauses

to dwell upon the hardships he is doomed to suffer in order to reach the

new goal. The malady rises to its critical point when the edge of the

wilderness is struck, but the temperature of determination to go ahead

falls rapidly as tho wrestles with fallen wood, swamp, and rushing wide

rivers loom up in deadly earnest. The faint-hearted, after battling a

few days against the hostile forces of Nature, abandon tho quest, and

return to the cities raging calamity howlers, just because the prize has

proved to be beyond their grasp.

Among the earliest

participants in the rush is the packer with his train of sturdy,

animals. The community in the heart of the wilderness must be kept going

from the outposts of civilization ; a link of communication must be

established to take in provisions, clothing, and a hundred and one other

necessaries of life. It is not long alter a new land has risen in the

commercial firmament before strings of mules and ponies, driven by the

rugged packers are to be seen winding their tortuous ways through tho

dense forest, laden with an assortment of articles, from bags of flour

to dissembled iron stoves, clothing, tools, and what not. It is the

packer, with his devil-may-care 3pirit, who keeps the new country alive.

The packer is a human

puzzle. Meet him in the city, and he gives you the impression of a

gentleman at large, with his immaculate white linen, the latest thing in

tweeds, his feet decked in gaily coloured hose and encased in the most

fashionable of footwear, with kid gloves and a soft Homburg hat. As a

rule, you will find him in the saloon, treating all and sundry with that

lavish hospitality born of the bu3h. Probably he has just come in from a

long sojourn in the wilds and has found a large sum awaiting him a« the

reward for his labours. He has drawn his notes, and is trying to rid

himself of them with the utmost speed. When his pockets have been

depleted, he sheds his stylish attire, carefully presses and folds it

away, to hit tho trail once more.

Meet him in the bush,

with his team jogging wearily along at about two miles an hour, and he

is the antithesis of him whom you saw in the city; the gentleman of

civilization has devolved into a tramp of the woods. His nether garments

are decidedly the worse for wear, and invariably saturated like a sponge

from contact with the soddened brush, or a plunge through a creek. The

white linen has given way to a rough flannel shirt and a coarse sweater.

His hat strives valiantly to preserve some sign of respectability, while

his face and hair are unkempt. His feet are shorn of tho gay hose, and

aro armoured in the nudo condition with the roughest and most ungainly

of leather boots, built for wear and not for comfort or appearance. Ho

trudges along in silence, viciously chewing his quid o£ tobacco to keep

his throat moist and the inner man quiet until camp is pitched. Now and

again he gives vent to a violent, raucous outbreak of invective to spair

his lagging animals into quicker movement. Yet he is absolute

contentment. He has had enough, so ho relates, of the city; a few weeks

in the silent bush is an excellent antidote to boisterous revelry, as

well as being an invigorating tonic to a shattered constitution. But

when ho gets batfk to the city again—well, there will be something

doing.

The packer is emphatic

in his statement that his vocation is the finest going. None dares to

dispute his contention. Out of doors the round twenty-four hours, living

in the purest atmosphere, knocking up against the elements day in and

day out, and good pay. He has no worries or anxieties beyond the safety

of his animals and packs, is his own master, has as much to eat as he

desires, though it may be limited in variety. What more can any man

want?

I met one of these boys

of the trail. He was the eldest son of a prosperous English family, his

father being a well-known merchant prince of London. “Guess the family

would have a fit if they could see me in this rig-out,” he grinned, as

he made water squelch musically in his boots, and wrung out his sweater.

He bad just ploughed his way through a slough, and the water was

streaming from him like a dog which has just emerged from the water.

“The pater kicked at me coming out here. I went home two years ago. and

he said he’d fix mo up in his office. I wont down to the City with him.

but I only stayed an hour. I borrowed the money from him to come back

here. The books, desks, figures, and the monotony of it all, fairly

scared me. I never regained my wits again until I was astride my old

mare and had hit the trail once more.”

At first sight packing

may appear to be an inferior occupation. Yet from the verdant farms

lining the St. Lawrcnce to tho yawning valleys on the Yukon the

pack-train is indispensable; without it Canada would stand still It is

the ship of the bush, ploughing steadily to and fro, bringing news of

the outside world to the isolated communities settled two or three

hundred miles from the nearest post-office, and keeping civilization

posted up as to how things are going up yonder. It appeals to the

average young Britisher who loves to roam in st arch of excitement and

adventure, and it must be confessed that as a packer he will get mere

than the average share of such fare.

I have been asked

often, “What are the qualifications for a packer?” There is only one

reply—the ability to stand “roughing it.” It is the finest drilling for

manhood, and the senses become timed to a high pitch of perfection. The

bufferings are hard and frequent. When I hit the trail for the first

time, my knowledge of the horse was typical of the city-bred individual,

and I was just as anxious to keep out of the rain. But in a month I

caught the true packing spirit—let everything go hang! It mattered

little if I were soaked to the skin; dog-tired, 1 tumbled into dripping

blankets at night, with a rook as a pillow. Rain, snow, and sunshine,

were accepted with indifference, while finding one’s way through the

trackless forest possessed its own peculiar fascination. It was with

keen regret that I shook the mud and dust of the trail from my feet to

return to the city once more.

Packing is an art. One

does not grasp in a few days the right and wrong way to stow aborted

articles on a horse’s back so that the weight is well distributed, and

not likely to hinder the movement of the bca3t of burden. Even the

pack-horse, though docile, has its own idiosyncrasies, which must bo

studied; while the diamond hitch is not mastered at first sight,

especially when the master of craft under whom you are picking up

knowledge as best you can, has the unhappy nack of varying the throw in

order to perplex you.

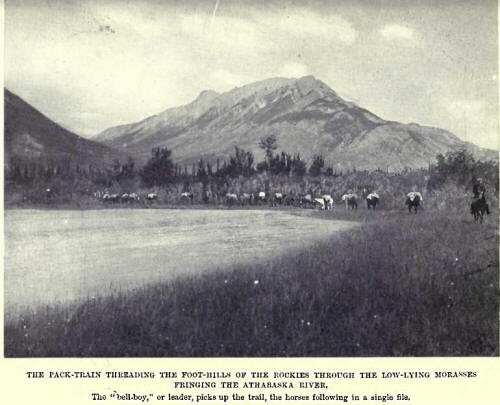

The task of the

bell-boy probably is the most unenviable. He leads the way. Ki« animal

has a loose bell round its neck, the tinkling of which summons the

others in Indian-nlo to follow in its footsteps. The bellboy picks up

the trail, and dears tin way for the rest of the train. If the going is

good, his work is easy, though terribly lonesome, as probably his

colleagues are a quarter of a mile or more behind him. He has to keep

going the whole time, because the moment he stops the following animals,

deprived of a leader, wander aimlessly into the bush on either hand,

producing the worst state of confusion. In the course of an hour or so

the animals commence to feel hungry, and grab mouthfuls of fodder from

the wayside. The train stretches out into a ragged, lagging line, and

the bell-boy has no little difficulty to entice the leading pack-horse

to keep closely to his heels.

It is when the

obstacles of the trail are encountered that the bell-boy’s troubles

commence. Caution is demanded, and whatever the character of the

obstruction the speed of the pack-train slackens. The ocher packers

liven up to keep their animals under control, crashing through the bush

on either side, and laying out with their lariats to prevent straying.

The pack-horse is a curious animal. Unless it can be kept to its steady

jogtrot, it thinks it may ramble off into the brush on either side of

the trail; and when two men have thirty animals to keep in hand, the

task is by no means easy.

The forest fire raises

many misgivings in the bell-boy’s mind. It is no unusual circumstance

for a fierce fire to pile up such a barrier of blackened trunks upon the

trail as to render progress merely a matter of feet per hour. It may be

impossible to wind in and out among the prone monarchs of the forest in

a wild zigzag. Then there is no alternative but to have out the axes and

to cleave a way through the mass. The work is hard and exacting,

especially If the brush is alight and smouldering, causing the animals

to plunge, rear, and stampede in the hot ash.

The slough is a direct

contrast to the forest fire. There is no trail, as the ooze covers up

all footprints, and the marsh grass, growing luxuriantly to a Wight of

five or six feet, completely hides the ground beneath. The bellboy has

to find a way somehow. With hir. characteristic dare-devilry he plunges

straight into the morass, trusting to tho instinct of his beast to get

him through. The animal sinks up to its girth in the ooze, and tears its

way blindly forward under the action of the spurs, splashing its unlucky

rider from head to foot with slime and water. The bell-boy holds on like

grim death, steering his horse first to the right and then to the left,

in the hope of getting through without parting company with his seat. If

the horse comes to a stop and evinces a timidity which cannot be

subjugated by spur and lariat, the rider jumps off, and wading, it may

bo over his waist, pulls his unwilling steed behind him. When dry land

at last is regained, both horse and rider shake themselves like dogs to

get rid of the superfluous mud. The drivers behind are having an equally

lively time. The laden animals hesitate to follow in the bell-boy’s

wake, and so the drivers, crashing and splashing in a wild mel6e force

them across the marsh, hallooing frantically, cursing viciously, and

laying out right end loft with the lariats until one and all are safely

across.

When a broad, rushing

river, especially among the mountains, has to bo crossed, the going is

still more lively and dangerous. The anima’s are relieved of their

loads, which arc transported upon a crude raft, fashioned from dead

tree-trunks roped together. Manipulating such an ungainly craft across a

river, the current of which swings along at a merry pace, and with

unseen obstructions bristling everywhere, its no easy tack: but the

packer never worries about a difficulty until it hits him squarely. and

then he sets to work to extricate himself as best he can. Snags,

sandbars, rocks, none of which may appear above the surface of the

rippling water, have to be dodged. The packer finds cut their existence

by running into them ; that is the only manner in which the unknown

waterways can be navigated. When the goods have been got safely across,

then the horses have to be handled. A runway is hastily improvised upon

the river bank, leading into the water by means of a rope corral. The

animals are rounded up, hustled into this enclosure, and then the

packers gather around and indulge in a sudden outbreak of Indianism.

They shout, dance, shriek, and yell in the most fiendish manner,

possibly increasing the volume of discordancy by letting off a few

revolver shots into the air. The animals, startled, endeavour to rush

pell-mell into the bush, but, being hemmed in, and tickled up now and

again by the thick end of the lariat, they presently take a headlong

dive into the river, as the only avenue of escape from the pandemonium,

and. frantically lunging out with their feet, as if demented, swim

around until one- more sagacious than the rest, strikes out boldly for

the opposite bank, to be followed by the whole bunch, snorting and

blowing viciously as they feel the sucking of the undertow. Gaining the

opposite shore, one and all plunge into the bush. The packers follow at

leisure, and are soon on the heels cf the animals; getting them once

mere into some semblance of control.

But the curse of the

trail and the despair of the packer is the muskeg, the Indian name for

swamp. Old boys who have pushed through the worst stretches of

wilderness between the Atlantic and the Pacific give an involuntary

shudder at the mention of the word “muskeg.” I myself have had and seen

some stirring incidents grappling with this enemy. More often than not

the situation is complicated by the presence of a creek, springs, or a

large, deep pool of unseen, stagnant water. Superficially the saturated

accumulation of decayed vegetable matter looks as sound as a brick

pavement, as, indeed, it is as a rule to human feet; but when the

pack-horse ventures forward, its legs descend into the mass like sticks,

and it is not long before it has sunk up to its girth. Then it lunges

out desperately in all directions in the effort to free itself from the

sticky, glutinous mad. but every struggle only causes the animal to be

sucked deeper into its unsavoury couch. The pack on its back hampers its

movements, and, being a dead weight, seem?, to press the animal

irresistibly into the greedy morass.

When a horse becomes

stalled in the muskeg, lively times are expected. The packers rush

forward, often knee deep. The packs are torn off hastily and tossed on

one side. The absorbing question is to save the animal from exhaustion

and suffocation. Ropes are lassoed round its head, and while, perhaps, a

couple tug desperately, another pushes might and main on the animal’s

flanks. The brute endeavours to assist its rescuers, but the wicked

sucking, squelching of the slime betrays the fact that the mu&keg is

determined not to let its victim escape without extreme effort. The mud

flies in all directions, but the packers close their eyes, and hang on

like grim death. If the horse can be got into an upright position, those

who arc pushing slip their shoulders under the flanks, and strain

desperately to prise the animal up. If it is wellnigh exhausted. a sharp

eye has to be kept open to spring clear when the animal relapses back,

and a breather is taken for the next attempt. Even when the creature

falls from sheer exhaustion, and cannot assist its helpers, the rescue

is not abandoned. All the m haul on to the neck-rope in the endeavour to

pull the animal out of the hole by sheer physical force. So tightly does

the slime grip that, when at last the animal is hauled clear, the last

sport often sends the packers sprawling into the slough. But one and all

scrape as much mud from their faces as they can, vault into their

saddles, and jaunt along merrily in expectation of the next excitement,

allowing the heat of the sun to dry their clothes, from which the mud is

removed more or less, later in the day.

The packer’s life teems

with excitement and adventure, and no other vocation ever would appeal

to these happy-go-lucky spirits. No two days are alike in their

existence. Even when the rain is pelting down, lashing the face like a

whip, and drenching Lhe clothes, they jog along whistling and humming in

perfect complacency. When the camping-ground is reached, a roaring fire

is built up, and. standing around, they dry themselves in its welcome

heat, their forms enveloped in a sizzling steam bath. Then they turn

into their blankets, which perhaps are reeking with water, but they are

soon in the arms of Morpheus, and far more comfortable than the city man

buried beneath snow-white linen upon a feather bed.

Is the occupation well

paid? That depends from what standpoint the calling is viewed. It does

not build up millionaires, although many prosperous merchants ot Canada

to-day can recall the days when they followed it, and thus secured the

urgent dollars to lay the foundations of a fortune. The pay varies from

6s. 0d. to 8s. 0d. (or more) a day the whole time the packer is on the

trail. This docs not seem a princely wage, considering the conditions of

life and the arduous nature of the work, but this is in addition to

living, and there are no personal expenses when trailing. Often a

journey will last for a couple of months so that when the packer returns

home he has from £18 to £24 clear awaiting him Seeing that the

pack-train can only be called into requisition while the country is

open, and that the demand during that period is greater than the supply,

the packer ha3 straightforward, steady employment for seven or eight

months, during which time he can make from £63 to £100 clear.

Several of the thrifty

boys have become firmly established financially at this work. One I met

stuck steadily at it for three years, and at the end of that time found

himself possessed of a bank balance of £200. He resolved to start

business on his own account, and, settling down in one of the smaller

towns, opened a general store. It proved a good investment, but,

unfortunately for him, he could not shake oil the call of the wilds, so

he placed a manager in charge of the business. The summer months he

spent along the trail, and the winter he put in at his store. He

confessed that he was making a good thing of the dual occupations; the

trail brought him in a steady £100 a year clear, while the store

contributed another £200 to £300 per annum.

In another instance I

ran up against a young farmer. He war, firmly established upon his 160

acres, and was “making good” at mixed farming. He was from the southern

English counties, emigrated several years ago, could not fit himself in

a suitable niche of employment in Eastern Canada so as a new-comer beat

the train to the West, or, in other words, stole transportation by

riding in freight cars, and on the roof of the expresses, with his arms

cuddled round the pipe from the cooking-stove within to keep himself

warm at night. He reached the West considerably the worse for wear, and

without a dollar in hip pocket, was taken on a paek-train, soon acquired

the details of the business, made £80 during the first summer, and

cleared up another £40 during tho winter, all of which he husbanded.

Three years of this life gave him the wherewithal to settle upon the

land, and when asked what his present position was worth, briefly

replied, “About £5,000.” There was only one worry on his mind, but that

was trivial. “I owe the railway company for the tides 1 sneaked to get

out here, but 1 guess, as they have had me over transporting my produce,

we are about quits now.”

The daily round is

certainly strenuous. The average progress is about fifteen to twenty

miles per day. according to the distances the camping-g/ounds are apart.

The packers pull out of camp about seven in the morning, and keep going

steadily until they reach tho next camping-ground, which is selected for

abundance of feed for the horses, and the close prcximKy of water and

wood for themselves. Reaching camp, the horses are relieved of their

packs and are turned adrift in the bush to wander and graze in search of

food and rest as they please. The packs are piled in a heap, protected

with a canvas sheet or fly ; the camp fire is built up, and the

preparation for the meal hurried forward, as seven hours in the saddle

provoke a tremendous appetite.

Dinner discussed, the

time is whiled away as the packer inclines. So far as the food is

concerned, there is little anxiety. The packer is a more or less

accomplished cook —certainly sufficiently so to meet the requirements of

the trail, with pork and beans, fried bacon, boiled rice or dried

fruits, oatmeal or mush, as maize porridge is called, in the morning,

and bannock, with tea as a beverage. None of these dishes takes long to

prepare, and their monotony is relieved under favourable circumstances

by tinned fruits and jams.

The packer’s couch is a

rough blanket or two—those thrown over the horses’ backs beneath the

pack-saddles suffice—laid on the ground before the fire under a canvas

fly or else a small A tent. The packer turns into the blankets without

troubling to disrobe himself, especially if wet—1 myself have not taken

off my clothes for weeks at a time—soon after darkness has settled upon

the land, and the exertions of the day generally are sufficient to

insure a sound night’s rest.

Shortly after the sun

has kissed the dew-laden hush the packer is astir to hustle his horses

into camp. This is the most arduous part of the day’s work, to my way of

thinking. The horses having been turned adrift overnight, have wandered

all over the face of the earth in search of food and rest. If the feed

is good, perhaps they are within a mile or two of the camp’s precincts;

otherwise they may be miles away. At all events, the result is the same.

The packer has got to find them and to round them up. Some animals

appear to be possessed of a peculiar roaming instinct, and these are

always a source of anxiety.

The packer, in his

sweater and trousers, and with a bridle thrown over his shoulder, tramps

off through the soaking wet bush to pick up the trails of the creatures.

It is simply a blind drive through the dense undergrowth, with the

branches whipping the face and saturating the clothes, until a track is

picked up, and this is followed until the i inkling of the bells around

the horses’ necks betrays the fact that they are close at hand. Some old

warriors of the trail are very canny, however. They can hear the packer

trudging through the bush, and, realizing the import of his approach,

they draw under cover and stand as still as mutes, permitting him to go

blundering on without observing hia quarry. Then, when he is some

distance beyond, they scamper off in the opposite direction. These wily

animals are anathema to the packer. When the morning is wet, rain is

falling heavily, and the going is broken and hard to him on foot, he

curses equine wiliness in no uncertain manner. Then, again no little

skill is required to determine the latest track, as the animals pass and

repass a given point several times in the course of the night, leaving a

bewildering criss-cross of trails. The tender-foot is nonplussed until

he can read the riddle of the bush like the expert, but ho buys this

knowledge very dearly.

When one animal is

caught, the rest is fairly easy, as the packer now has a means of

covering the ground with less personal effort and fatigue. Still, it is

no unusual circumstance for the horses to spread themselves over twenty

square miles of country in the course of a night.

The return to camp is

always exciting. A few faint halloos are heard from the distant bush,

interspersed with excited neighings and a wild jangle of bells.

Presently there is a commotion in the growth. “Here they come!” shout

the boys in camp, and every one starts up to assume a commanding

position around the corral which has been improvised by passing ropes

from tree to tree, making a small enclosure. The excited equines,

throwing their heels into the air in mad glee, and with the rider in mad

pursuit, waving his lariat, rush towards the camp as if determined to

run one and all down. The waiting boys deliver a startling, wild halloo,

the animals swerve, and before they realize the fact are within the

corral. Then the animals are tethered, and their captors, as hungry as

hunters, demolish the crude trail breakfast with great gusto, and in a

manner that would frighten a housewife into hysterics.

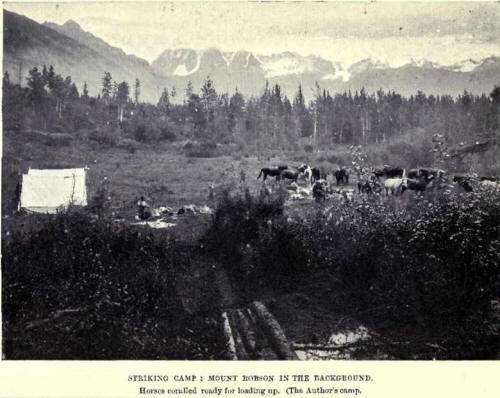

The matutinal meal

finished, there is no pause. Saddles and packs are hauled out and

transferred to the backs of the ponies and mules. In the course of an

hour the whole train has struck the trail again to settle down to a

steady two-miles-an-hour plod towards the next camp.

Why the calling makes

such a powerful appeal to the young adventure-seeking youth is because

of the romance with which it is associated. It takes him into new and

unknown regions, to see something of which the outer world knows

nothing. The average packer revels in this adventure, and often refrains

from making the same journey twice, except at long intervals. He prefers

the excitement of a new trail. The nomadic existence appeals to the

British temperament. Even the bell boy is to be envied at times when

game is to be encountered along the trail, for fur and feather are often

met in the bush. A shot from a “22” at a fool-hen, partridge, or grouse,

relieves the tedium of the journey, and provides welcome contributions

to the stockpot.

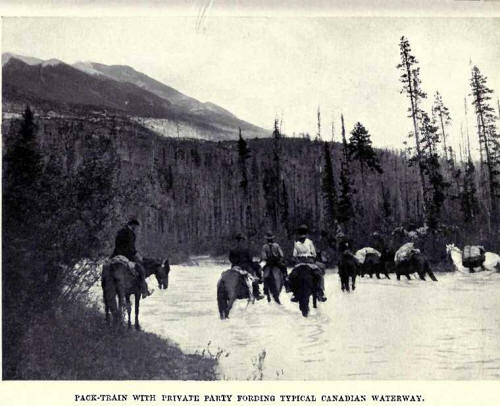

Accompanying private

parties is a gentlemanly aspect of the packer’s existence. The journey

may be undertaken purely for pleasure, exploring the resources of a new

country in company with a Government official, a mining engineer, or

what not. In any event, the life is much the same. The train for the

most part moves along leisurely, the distance covered each day is short,

and there are frequent spells of three or four days in a camp to break

the monotony of taking to the trail every day. It is no uncommon

circumstance for such a party to be absent for four or five months, and

the packer can expect confidently £50 or £60 when he returns, this sum

generally being inflated with substantial gratuities, especially if the

journey has proved productive. On such trips the packer is treated as

one of the party, participates in the meals, secures ample supplies of

tobacco, a wide variety of comestibles, and other little delights. The

life is less strenuous than packing freight, which is a distinctly

different occupation. |