|

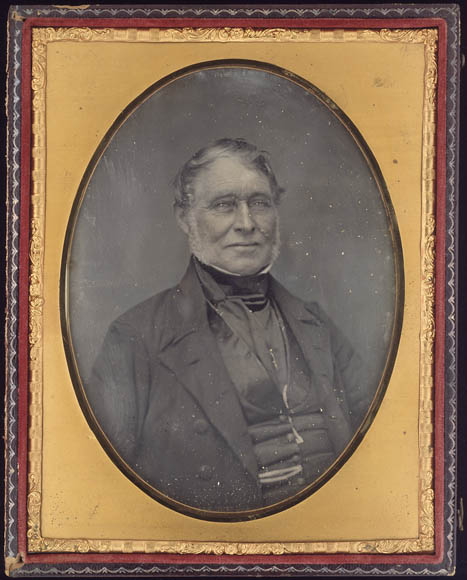

McDONALD, ARCHIBALD,

colonial administrator, author, fur trader, justice of the peace, and

surveyor; b. 3 Feb. 1790 in Glencoe, Scotland, son of Angus McDonald,

tacksman of Inverrigan, and Mary Rankin; m. first 1823, according to the

custom of the country, the princess Raven (Sunday) (d. 1824), daughter

of Chinook chief Comcomly, at Fort George (Astoria, Oreg.), with whom he

had one son, Ranald McDonald*; m. secondly 1825, also according to the

custom of the country, Jane Klyne, a mixed-blood woman with whom he had

twelve sons and one daughter; marriage confirmed by Christian rite 9

June 1835 in the Red River settlement (Man.); d. 15 Jan. 1853 in St

Andrews (Saint-André-Est), Lower Canada.

Archibald McDonald was enlisted in early 1812 by Lord Selkirk [Douglas*]

to serve as clerk and agent for the Red River settlement. In Scotland he

assisted in the recruitment of the second group of settlers, who sailed

in 1812. Originally designated to travel with this group, McDonald was

held back by Selkirk for training and in 1812–13 he studied medicine and

related subjects in London. In June 1813 he sailed from Stromness,

Scotland, with a group of 94 Kildonan emigrants on the Prince of Wales

for York Factory (Man.), as second in command to Dr Peter Laserre.

Typhus broke out during the voyage and Laserre, who was among those

infected, died on 16 August, leaving McDonald to take charge of the

party. The captain of the ship was anxious to be rid of his passengers

and landed them at Fort Churchill (Churchill, Man.), where they spent an

uncomfortable winter, poorly equipped and short of provisions. In the

spring McDonald led 51 of the settlers, most of them in their teens or

early 20s, on snow-shoes 150 miles south along the shore of Hudson Bay

to York Factory, a march of 13 days. They then travelled by boat up the

Hayes River to Lake Winnipeg and arrived at the settlement on 22 June.

The rest of the group reached Red River two months later.

Before his departure from Great Britain, McDonald had been appointed to

the Council of Assiniboia, a body created by Selkirk to aid the colony’s

governor, Miles Macdonell, and during the winter of 1814–15 he served as

one of Macdonell’s principal lieutenants. In the spring of 1815 Cuthbert

Grant and the Métis, encouraged by the North West Company, who were

opposed to the establishment of the Selkirk settlement, openly harassed

the colony, attacking the settlers and stealing livestock, until in June

they forced the abandonment of the colony. McDonald proceeded with a

group of the settlers to the north end of Lake Winnipeg where they were

joined by Colin Robertson, who took charge of the colonists and returned

to Red River to re-establish the colony later that summer. McDonald

returned to England to report on the fate of the settlement and while

there prepared an account of the events leading up to the abandonment of

the colony, which was published in London in 1816.

In the spring of 1816 McDonald joined Selkirk in Montreal. There he

wrote four letters, published in the Montreal Herald, in reply to the

Reverend John Strachan*, who had written A letter to the right

honourable the Earl of Selkirk, on his settlement at the Red River, near

Hudson’s Bay (London, 1816), highly critical of Selkirk and all those

associated with the colony. In August he was at Fort William (Thunder

Bay, Ont.) when Selkirk arrested several NWC partners, including William

McGillivray*, and seized the post. McDonald then returned to Montreal

and in the spring of 1817 took charge of the group of soldiers from the

disbanded De Meuron’s Regiment recruited by Lady Selkirk to reinforce

the troops Selkirk had taken west with him the year before. After

conducting this force to Fort William, McDonald turned back to Montreal

and sailed for England in the fall. In 1818 he returned to the Red River

settlement by way of York Factory to assist in the administration of the

colony. In February 1819 he was among those, with Selkirk, indicted on

charges of “conspiracy to ruin the trade of the North West Company”

arising out of the events at Fort William three years earlier, but after

many delays in the courts the charges were finally dropped.

In the spring of 1820 he joined the Hudson’s Bay Company as a clerk and

was posted to Île-à-la-Crosse (Sask.). The following year HBC governor

George Simpson sent him to the Columbia district, on the Pacific

northwest coast, under chief factors John Haldane and John Dugald

Cameron. He was instructed to prepare an inventory of the goods at the

NWC posts acquired by the merger of the NWC and the HBC in March 1821,

and then he served as accountant at Fort George. In 1826 he took charge

of Thompson’s River Post (Kamloops, B.C.) and in the fall of that year

he explored the Thompson River to its junction with the Fraser,

accompanied by the Okanagan chief Nicola [Hwistesmetxē'qen]. From his

observations he prepared a map of the region which delineated for the

first time drainage patterns and contours.

McDonald was promoted chief trader in January 1828 and travelled east

with Edward Ermatinger* in the spring to attend the Northern Department

council meeting at York Factory. On the return journey to the west

coast, McDonald accompanied Governor Simpson, who was proceeding west

for a tour of inspection. Typical of all of Simpson’s travels, this

voyage was completed in exceptional time: the 3,261-mile trip from York

to Fort Langley (B.C.), following the northern route from Cumberland

House (Sask.), across the Methy Portage (Portage La Loche, Sask.), down

the Clearwater River, up the Peace, and finally down the Fraser River,

was completed in 90 days. The party ran the treacherous rapids of the

Fraser, including the lower section that Simon Fraser* had not attempted

in 1808.

At Fort Langley, McDonald took over the direction of the post from James

McMillan. He remained there until 1833, conducting a trade with the

coastal Indians in competition with American maritime traders and

diversifying the activity of the post by some agricultural production

and by the drying and packing of salmon and the cutting of lumber, both

for shipment to the Columbia district’s headquarters at Fort Vancouver

(Vancouver, Wash.). In 1833 he left Fort Langley and established Fort

Nisqually (near Tacoma, Wash.) before heading east to York Factory in

1834 and then on to Great Britain for a year’s furlough.

McDonald was back in the Columbia in 1835, and took charge of Fort

Colvile (near Colville, Wash.). Built by John Work* in 1825–26, Fort

Colvile was important for its farming operations. When McDonald took

over, there were more than 200 acres under cultivation, and in 1837 he

noted that the three cows and three pigs brought to the post in 1826 had

multiplied to 55 and 150 respectively. He developed the farm on a large

scale, contributing provisions for the HBC posts to the north and after

1839 for the Russian American Company, based at Sitka (Alaska). He was

promoted chief factor in 1841.

In September 1844, plagued by ill health, McDonald set off for

retirement in Lower Canada with his wife and six youngest children;

another was born en route. They wintered at Fort Edmonton, where in May

1845, before resuming their journey, three young sons died of scarlet

fever. McDonald and his family stayed in Montreal for three years and

then, in 1848, settled on a comfortable farm by the Ottawa River, near

St Andrews. McDonald played an active role in local affairs, serving as

justice of the peace and surveyor, and in 1849 he led a delegation from

Argenteuil protesting the provisions of the Rebellion Losses Bill to the

governor-in-chief, Lord Elgin [Bruce*], in Montreal. In January 1853,

after a few days’ illness, McDonald died at his home, Glencoe Cottage.

During his years in the Columbia district, McDonald had demonstrated a

lively interest in the collection of scientific specimens. He

corresponded with the British Museum, the Royal Horticultural Society,

and Kew Gardens (London), sending botanical, geological, and animal

specimens from the region. He met the British botanist David Douglas* at

Fort Vancouver in 1825 and helped in the collection of the impressive

selection of plants and seeds that Douglas carried back to England.

Another botanist, the German Karl Andreas Geyer, passed the winter of

1843–44 in McDonald’s company at Fort Colvile. In September 1844

McDonald discovered the silver deposit on Kootenay Lake which was later

developed as the Bluebell Mine.

Alert, industrious, a man of broad interests, McDonald had a facile pen

and left a large body of journals and correspondence which provides

valuable information on the native tribes he lived among during his

quarter century in the west. His descriptions of family life at remote

fur-trade posts are among the few accounts available to social

historians, and his papers are rich in documentation on plant and animal

life as well as on the early efforts in agriculture, lumbering, and

fisheries in the Pacific northwest.

Jean Murray Cole

See also

Volume 4

No. 2

(pdf) of the Beaver Magazine |