|

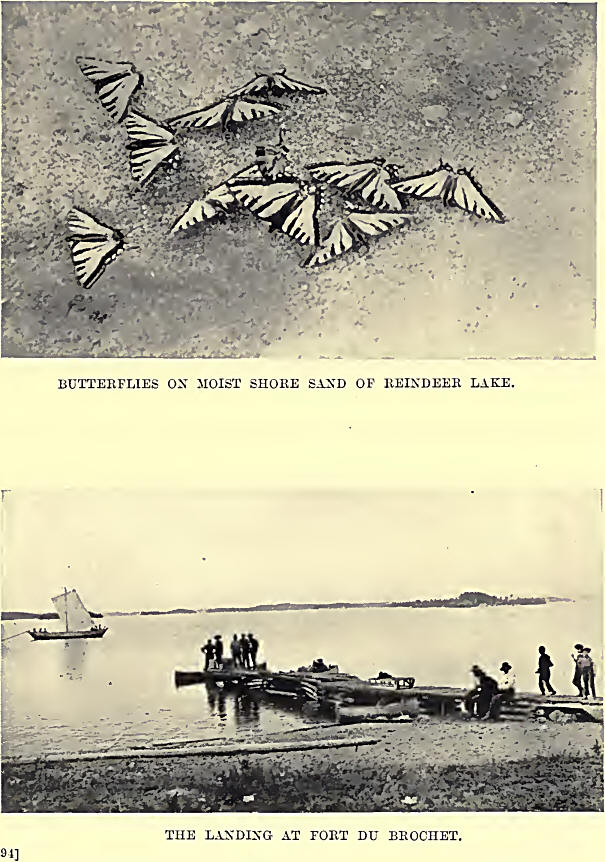

Reindeer Lake! Fort Du Brochet! Names remote on the map

of Canada, names situated in that Far Northern hinderland where so few

have come into being that each denominates a kingdom of virgin country

which lies, unknown to our race, on all sides of the point that has been

discovered. To me such names are big with possibilities, big with the

attraction of things mysterious, big because they shelter a country that

is waiting the races of the future. Yet to you, no doubt they are mere

names of Lake and Post to be glanced over and forgotten, and given back

to the gigantic soundless wastes of semi-Arctic Canada. Because they are

hidden away in far-off distance they hold what fame they have in the

still unravelled clouds, and the secretive silence, of the ever-passing

years.

Reindeer Lake is between longitudes 102° and 103° and

extends north to latitude 58°. It is a vast sheet of water which

stretches 140 miles north and south, and forty miles across where its

width is greatest. It is in a country of rock, and muskeg and low-lying

hills which arc filled with silence and unseen creatures.

The lake contains countless islands (some thousands)

which are wooded, as are the land shores, with the strong character of

dark-peaked Spruce and Scrub Pine, and a few Tamarac and Birch. The

island shores, which are bordered with Willows at the fringes of the

forest, are rugged and grey with rock and boulders, brightly relieved

for occasional stretches with long low bays and points of spotless,

warm-toned sand. Distant stretches of water open up between 'the

islands, low smoke-blue hills show faintly in the distance, miniature

traceries of dark trees rise, like masted ship, out of reflecting

shadows on the far lake surface where hidden islands lie, and right out,

as if at the end of the world, the waters die away into the clouds where

no land is in sight. It is a wonderful lake of hidden distances which

appear and disappear in all directions behind the foreland, as onward

you travel through a truly bewitching fairyland. And over the clear blue

waters of the lake, reaching far into the great distances, reaching even

beyond into unseen but imaginable places, there reigns impressively the

weight and solemnity of an unseen Spirit. It is the Spirit 6f the

North—silent grandeur, and vastness, and untouched purity of a Virgin

Land lending awe and greatness to Creation. It is the dominance of that

Spirit which makes man feel, when in the great grave presence of it, how

impotent, how insignificant a part of the Universe he is, and how humble

he should be.

There are two Trading Posts on Reindeer Lake : one, a

winter post, is on Big Island at the south end at the head of Reindeer

River; the other, Fort Du Brochet, the chief Post of the territory, is

on the north mainland near the mouth of the Cochrane River. The two

Posts are, depending on wind, five to six days’ canoe journey apart,

while the York Boat of the Hudson Bay Company —a cumbersome, wide-beamed

sailing craft of some forty-foot keel—with following wind (and the

Indian crew always wait for such a wind when about to make the voyage),

and travelling day and night, can accomplish the distance in two days.

It was in mid-July that Joe and I in our solitary canoe

approached the north end of Reindeer Lake and sought the inlet which

would hold some sign of habitation.

Night was creeping down over the earth, and the shores

were darkening to blackness when our journey on the lake drew to a close

and we neared the Post of Fort Bu Brochet. The gladness of a summer’s

day was folding its spirit in repose, and the inflexions of a score of

tiny nature sounds were fading away into the darkness, though still the

strained ear caught the laughing trickle of water against the canoe and

the lowspeaking lap of the gentle waves as they came and went with the

lazy northern breeze. Our approach was unheralded, and the lone canoe

stole softly inshore, where cabins stood solemnly silhouetted against

the wistful sky. Dim figures moved on shore to the left, and low voices,

in native conversation, rose—then died away. Stars peeped out, and the

Northern Lights grew clear in the overhead sky. A rising fish

splashed—and another. . . . Then silence reigned.

The canoe was run in on the sand close by the shadowy

landing, and my companion and I stepped ashore to pick our way up the

rough path to the Fort. Night settled down to death-like silence. . . .

The Spirit of the North was in the air, and in the solitude of the

lonely Post.

After rounding an island promontory Fort Du Brochet is

approached, where its scanty settlement of miniature dwellings stands

grave and grey in one of those hidden inlet bays so common to all

waterways of the rugged North. The small gathering of teepees and cabins

shows suddenly and at close range before the vision of the voyageur, and

he welcomes them, after his long, hard journey through unpeopled

country, as an unexpected find. He exclaims with pleasure at the sight

of habitations, and excitedly anticipates the joy of conversation with

the white or half breed trader at the Fort. It is the way of men on the

outer trails to be delighted with such rare meetings with mankind, for

as they gain the freedom of the wilderness the mind looks ever back to

its harvest of memories of companionship, and looking back grows ever

hungrier for the voices of their kind. Those primitive shelters, artless

and somewhat uncompromising in line and colour, are therefore as welcome

to the traveller as at other times might be the comfortable bungalow of

a civilised home. Indeed, it is possible they are more welcome, for in

the Silent Places men learn a greater appreciation than in a world of

ease.

The small, log-hewn, square-built cabins are

weather-beaten and grey like time-worn boulders on the wayside, and

stand solitary as sentinels on a bare, treeless, grass-grown knoll. The

Fort —the buildings of the Hudson Bay Company, comprising a house, a

trading store, and an assortment of outhouses—stands dominant on the

highest ground on the extreme cast of the knoll. To the west, strange to

say, is a tiny Catholic mission and church; the latter cross-planned, as

is the Roman custom, notwithstanding its insignificant size and crude

workmanship. At some little distance from the mission is the Trading

Store of the “French Company” (Revillion Brothers), rival traders to the

Hudson Bay Company, who here established a footing some ten years ago.

There are six cabins in the settlement occupied by part-blood or

full-blood Indians, who are at intervals in summer and winter employed

in the transport of furs and stores for the trading companies. White

fungus-like tents, in awkward discord with natural colouis, are pitched

here and there along-shore. They arc the temporary shelters of the ever

wandering Chipewyans, for alas ! the days of the mahogany-coloured,

smoke-soiled deer-skin (caribou or moose-skin) teepees have almost gone,

and their peaked pyramid forms range no more in native beauty along the

shore-front.

There is little stir of life around the cabins during the

long summer’s day, for the men are commonly away fishing or hunting or

“freighting” for the Company, and the few squaws, with their half-wild

children about them, keep chiefly to their dwellings. Occasionally the

dogs of the Post, which form the greater part of the population, give

voice to vicious quarrel or howls of deep-rooted melancholy'; but, as a

rule, they arc to be seen curled up in slumber here, there, and

everywhere, indifferent alike to the peace or desolation of the quiet

scene.

Such is the aspect of Fort Du Brochet, the furthest

inland post in the region and one of the hardest to reach from the

far-distant frontier. One may call it a rude settlement in a rude land

of water and cloud and wilderness: yet it had its native life of

quaintness and simplicity; and, above all, its summer days, and its

sunsets, and its Northern Lights of superb, wild, natural beauty.

The clear blue water of Reindeer Lake is teeming with

fish, and it is almost as wonderful on that account as it is for its

rare northern beauty. And those fish abound in water that is

exceptionally fine, and which, no doubt, gives to them wonderful growth

and well-being. An extract from the Canadian Geological Survey Report on

the country between Lake Athabasca and Churchill River, 1896, p.

99 d, states:

“A chemical examination of the waters from Reindeer Lake

and Churchill River was made by Dr. F. D. Adams in the Laboratory of the

Survey in 1882. In summing up the general results, Dr. Adams says: "Of

the foregoing waters that from Reindeer Lake is remarkable for the small

amount of dissolved solid matter which it contains; in this regard it

would take rank with the waters of Bala Lake, Merionethshire, Wales, and

Loch Katrine, Perthshire, Scotland. . . ”

There are, in Reindeer Lake, as far as is known to me,

eight different species of fish, most of which are to be found in many

of the waterways of the North, particularly where rivers flow, or have

connections to lakes. Many small land-locked inland lakes apparently

contain no fish, or very few, and those usually pike.

The fish contained in Reindeer Lake are, if we exclude

the small fry of which I had not sufficient time or opportunity to-take

account, Whitefish, Lake Trout, Back’s Grayling, or Arctic Grayling (?)

Pike, Pickerel, Red Sucker, Black Sucker, and lastly a small

herring-like fish, indigenous apparently to the south end of the lake,

which, after reference to specimens in the Museum at Ottawa, I believe

to be the Alaska Herring, or Mooneye Cisco.

The Whitefish is the great food fish, both for the

natives of Reindeer Lake and their sled-dogs. The flesh is white and

delicate, and delicious to eat; and one never tires of it even when it

is made a constant diet. They are caught only in gill-nets, and weigh on

an average between two and three pounds. The smallest fish I saw taken

weighed one pound, and the largest six pounds. In shape the whitefish is

narrow-backed, with a full, curved outline and deep-girthed sides which

are covered with silvery coarse scales; the head is small, and tapers

sharply to the fine-lipped, toothless mouth. The lower sides and belly

are silvery white, which is the striking colour of the fish, for they

look like bars of silver when freshly caught; the upper sides glint with

pale bluish-purple, or reddish-purple in some instances, and darken into

the brown over back, while the seale outlines there show black. The

dorsal fin is of ordinary size; not large, and brightly coloured like

the grayling, which it resembles somewhat in shape and size.

The Lake Trout is almost of equal food value to the

Whitefish, but it is never caught in great numbers by the Indians in

their set nets. The flesh of this fish is deep yellow, and firm and

full-flavoured; but one tires of it quickly as a regular diet, probably

on account of its richness in fat or oil. In shape those trout are full

and lengthily well proportioned; in colour the fine scales are silvery

white on the lower body, and white-spotted sage-green brownish above,

while there is a thin, dark, well-defined line along the centre of the

sides. They are powerful fish, usually weighing between three and a half

pounds and eight pounds, though they are occasionally caught of much

greater size. I secured one weighing nineteen pounds, and preserved the

skin, which is now mounted in the Saskatchewan Museum. One is recorded

weighing twenty-five pounds, caught near the mouth of Stone River. Those

trout can be easily caught on a rod by trolling a minnow or spoon, but

fly was tried on a few occasions without success, though fish were seen

breaking the surface of the water in all directions on suitable

evenings.

I had no occasion to catch more trout than the day’s

needs required, and on Reindeer Lake, particularly at the south end,

half an hour’s trolling was often sufficient to take a five to ten pound

basket; when the rod would then be put away. Fishing for food in this

way during the six days it took to travel from the south to the north

end of Reindeer Lake, my catch totalled thirteen trout, weighing

fifty-two pounds. I have often wondered what a whole day’s catch would

amount to in weight in those unfished waters, and almost regret I had

not occasion to make the test. .

Back’s Grayling, or Arctic Grayling (?) is only on very

rare occasions caught in nets by the natives. They probably do not live

long periods in Reindeer Lake, unless that when doing so they keep to

the deep waters and avoid detection. I have caught them below Reindeer

Lake on the Reindeer River, and above Reindeer Lake on the Cochrane

River. They are much given to frequenting the swift waters of river

rapids, and it is there that 1 invariably found them. They were caught

only on a small phantom minnow, which was the only lure I could induce

them to rise to, and weighed between one pound and a half and three

pounds. They were exceedingly game and fought splendidly in the swift

current. From an angling point of view they afforded more excitement and

fun than did the Lake Trout. I greatly enjoyed fishing for them, and

also the scramble over the rocks to reach their favourite “lies” in

surroundings where the river roared and tossed in companionable tumult.

In shape the Grayling resembles the White-fish, but the

flesh is not so firm, and white, and palatable, though quite fair

eating. In colour the upper sides are silvery brown, with glints of pale

blue, and also with slight yellow and red tints, while there are a few

widely spaced prominent black spots on the fore-shoulder; the back is

darker than the sides, and therefrom arises a very large dorsal fin,

almost a third of the length of the fish, which is brilliantly spotted

and streaked with many lights of deep purple and greenish blue; the

belly is blackish when the fish is first taken from the water, but later

it pales to white. It is, altogether, a brilliant rainbow-tinted fish

when seen swimming in the clear water, but quickly loses much of those

glints of colour when killed.

The Pike.—This fish, commonly called Jack-fish in Canada,

is that long-snouted, somewhat repulsive fish that everyone knows; and

it needs not description. Its flesh is quite edible in northern waters,

but nevertheless it is never used for food by the Indians when Whitefish

and Trout can be got. I caught many of those fish on spoon or minnow,

and took one on the rod weighing eighteen pounds.

The Pickerel, an American species of Pike, is very

similar to the above, and 'was almost equally common, and taken with the

same lures.

The Red Sucker is very plentiful in Reindeer Lake, and in

the river flowing into it, and is often caught in nets along with the

Whitefish. It is used for dog-food, but only seldom for human food,

although the heads cut off and boiled are often eaten by the Indians,

who consider the eyes a delicacy. The flesh is white, but somewhat soft,

and, if used for native food at all, is dried or smoked previous to

consumption. In shape they are a broad-backed, round-barrelled fish of

equal depth and width, while below the blunt-pointed snout is the

puckered, toothless, circular mouth from which they derive their name.

They weigh, as a rule, between two pounds and four pounds. In colour the

fish is white underneath, with the under-fins tinted with shades of

yellow and reddish chrome; the back and upper sides are medium dark

shades of blackish-brown with a clear pinkish tint overlying the ground

colour on the full length of the middle sides; the gills are yellowish.

In summer these fish are often seen in great shoals in

the clear shallow waters of rapids, and their colours then show beneath

the surface with oriental brilliancy.

The Black Sucker is very similar, but lacks the bright

colouring of the Red variety. Both are fish imperturbable by any kind of

lure, failing the possession of nets they may be speared in shallow

water.

The Alaska Herring or Mooneye Cisco is probably the

strange little fish which I saw taken for food purposes at the south end

of Reindeer Lake. None were caught at Fort Du Brochet at the north end

of the same lake, and the Indians declare they are known only at the

first-named locality, which appears very strange. I saw many of those

fish when passing on my way north, but omitted to secure specimens. And

unfortunately when I returned in winter the lake was frozen, and none

were procurable, though I tried.

I am unable therefore to - positively establish the

identity of this species, but certainly record the location so that at

least the presence of this small herring-like fish, which is apparently

peculiar to one particular section of water, may be noted and

investigated later by others if not by myself.

Reindeer Lake is undoubtedly very abundantly stocked with

fish, and one is prone to wonder if, in time, it will come to be

exploited by the white race on account of their food value.

But meantime its vast expanse lies

undisturbed; virgin—for one can almost discount the piscatorial

activities of the handful of Indians that now live on her shores, for

those are the activities of but a limited number of individuals who can

make no visible impression on this inland sea.

And so, of the future of Reindeer Lake one dreams, or is

prone to dream, when camped by her shores when the sun is lowering in

the gold-rippled, peaceful West, and the air vibrant with the churring

of nighthawks. . . . And, as you muse, and night creeps in, further

sounds of the wild awake and catch your acutely tuned ears, as does even

the minute rustle of a mouse in the grass in the breathless intervals of

overawing silence. . . . And at last, as if aware you had been waiting

for it, from the shadow-filled swamp near-by arises the elf-song of the

white-throated sparrow in mystic sweetness. . . . Then are you glad to

cease your ponderings; glad that Time has not changed this wonderland:

and that yours is the good fortune to camp on Indian hunting-ground, in

the Indians’ deep-shadowed land. |