|

In February, 1840, the Queen was united in

marriage to Prince Albert, of

Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, and in November of the same year the Princess Royal

was born. Intelligence of an attempt to assassinate the Queen reached

the Island towards the end of July. The culprit was a lad named Edward

Oxford, a servant out of place. As Her Majesty, accompanied by Prince

Albert, was proceeding in a carriage for the purpose of paying a visit

to the Duchess of Kent, at her residence in Belgrave Square, they were

fired upon by Oxford, who held a pistol in each hand, both of which he

discharged. The shots did not, however, take effect, and it was

subsequently discovered that the youth was insane.

The governor, Sir Charles A. FitzRoy, having been appointed to the West

Indies, he was succeeded by Sir Henry Vere Huntley, who arrived in

November, 1841, and received the usual welcome. In March of the year

following died the Honorable George Wright. He had been five times

administrator of the government, a duty which devolved upon him as

senior member of the council, to which he had been appointed in 1813. He

also, for many years, filled the office of surveyor-general. He appears

to have discharged his duties conscientiously, and his death was

regretted by a large circle of friends.

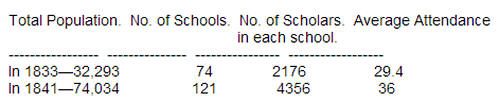

In February, 1842, Mr. John McNeill, visitor of schools, presented his

report, which furnished interesting facts respecting the progress of

education in the island. In 1833 the number of schools was

seventy-four,—in 1841 they had increased to one hundred and twenty-one.

While the number of schools had increased in this ratio, the number of

children attending them had in the same period been more than doubled.

In November, 1842, Mr. John Ings started a weekly newspaper, designated

The Islander, which fully realized in its conduct the promises made in

the prospectus. For thirty-two years it continued an important public

organ, when, for reasons into which it is not our business to inquire,

it was discontinued.

In March, 1843, a serious disturbance took place in township forty-five,

King’s County, when a large assemblage of people forcibly reinstated a

person named Haney into the possession of a farm from which he had been

legally ejected. The dwelling-house of a person employed by the

proprietor to protect timber was also consumed by fire, resulting from

the torch of an incendiary. Energetic measures were adopted to enforce

the majesty of the law.

On the sixteenth of May, 1843, the corner stone of the colonial building

was laid by the Governor, Sir Henry Vere Huntley. A procession was

formed at government house, and moved in the following order: masons,

headed by a band of music; then followed the governor on horseback,

surrounded by his staff; after whom came the chief justice, the members

of the executive and legislative councils, the building committee, the

various heads of departments, the magistracy,—the members of the

Independent Temperance Society bringing up the rear. Having, with trowel

and mallet, gone through the ceremony, His Excellency said: “The

legislature having granted means for the erection of a provincial

building, and the corner stone having been now laid, I trust that a new

era of prosperity will open in this colony, and am satisfied that the

walls about to rise over this stone will resound with sentiments

expressive of British feeling, British principles, and British loyalty.”

A royal salute was then fired, and three hearty cheers for the Queen

were given by hundreds who had collected to witness the proceedings. The

design was drafted by Isaac Smith, President of the Mechanics’

Institute, and the building was to be composed of freestone, imported

from Nova Scotia,—the estimated cost being nearly eleven thousand pounds

currency.

At the annual meeting of the Central Agricultural Society, a letter was

read from Mr. T. H. Haviland, intimating that in consequence of recent

public measures with relation to government house, the governor withdrew

his name from the public institutions of the island, and that

consequently he ceased to be the patron of the agricultural society. It

seems that the governor deemed the action of the assembly, in reference

to government house, illiberal in a pecuniary sense; but that was a very

insufficient reason for a step so fatal to his excellency’s popularity

and usefulness. The committee, with a negative sarcasm which the

governor must have felt keenly, simply passed a resolution expressing

regret that any public measures—in reference to government house—over

which the society had no control, should have been deemed by his

excellency a sufficient reason for the withdrawal of his name as patron

of the society; and a resolution was passed, at the annual meeting,

soliciting the honor of His Royal Highness Prince Albert’s patronage,

which, it is unnecessary to add, was readily granted.

In 1846 a dispute arose between the governor and Mr. Joseph Pope, which

excited considerable interest at the time, and which resulted in a

correspondence between the colonial office and the governor. It seems

that Mr. Pope had opposed strenuously, as an influential member of the

house of assembly,—he was then speaker,—a proposal to add five hundred

pounds to the governor’s annual salary, and this generated in the mind

of his excellency a very undignified feeling of hostility to Mr. Pope,

who had only exercised a right which could not be legitimately called in

question. Writing to Mr. Gladstone, then colonial secretary, the

governor said of Mr. Pope: “As for any support from Mr. Pope, I am quite

satisfied that in all his private actions, since the time of my

persisting in reading the speech, at the opening of the session of 1845,

respecting the debt he had accumulated, he has been my concealed enemy.”

The governor resolved to get quit of Mr. Pope, as an executive

councillor, and proceeded, in utter disregard of his instructions, to

effect that object by suspending that gentleman from his seat at the

board, without any consultation with other members of the council,

assigning to Mr. Gladstone, as his reason for dispensing with the usual

forms, that he had learnt from good private sources that the council, if

consulted, would have dissuaded the suspension of Mr. Pope, and would

have recommended the commencement of proceedings, by referring the

question to Her Majesty’s government. This reason could not prove

satisfactory to the colonial secretary, and the governor was ordered to

bring the case before the executive council, in which Mr. Pope was to be

reinstated as a member; and if they should advise his suspension, then,

but not otherwise, he was to be suspended from his office as an

executive councillor, until Her Majesty’s pleasure was known. Copies of

the despatches in which charges were brought against Mr. Pope were

ordered to be sent to himself, to which he had an opportunity of

replying; but, in the meantime, he prudently tendered his resignation to

the governor, in a long communication, in which he gave his reasons for

so doing, and in which he embodied a reply to the governor’s charges,

and condemned his gubernatorial action in very plain and energetic

terms.

The legislature met for the first time in the new colonial building in

January, 1847. An election for the district of Belfast was ordered to be

held on the first of March. There were four candidates in the field:

Messrs. Douse and McLean on one side, and Messrs. Little and McDougall

on the other. A poll was opened at Pinette. The chief supporters of the

two former gentlemen were Scotchmen, and of the two latter, Irishmen. A

riot ensued, in which a man named Malcolm McRae was so severely injured

that he died. Several others lost their lives in this disgraceful scene.

Dr. Hobkirk testified before the executive council that from eighty to a

hundred persons were suffering from wounds received in the contest. A

large force was sent to the locality, and, on the nineteenth of March,

Messrs. Douse and McLean were returned without opposition. There is not

now a more peaceful locality in the island than that in which the riot

took place; national prejudice and political rancor are lost in kindly

fellowship.

Messrs. Charles Hensley, Daniel Hodgson, and George Birnie having been

appointed by the governor commissioners to examine into all matters

connected with the state of the currency of the island, presented their

report in February, 1847,—a report which was creditable both to their

industry and judgment. It appears from a letter addressed by Mr. Robert

Hodgson, then attorney general, to the commissioners, that the legal

currency of the island was the coinage of the United Kingdom of Great

Britain and Ireland, and the Spanish milled dollar, which was valued at

five shillings sterling,—the debtor having the option of paying in

either of these descriptions of money. The commissioners drew attention

to the fact, that the currency of the island was greatly depreciated,

and that the process of depreciation was going on, which was proved by

the circumstance that the Halifax bank note of a pound, which twelve

months previously, would purchase no more than twenty-three shillings of

the island currency, was now received and disbursed at the treasury for

twenty-four shillings. This depreciation the commissioners attributed to

an extensive issue of unconvertible paper, both notes and warrants,

combined with a growing distrust of the economical administration of the

finances of the colony, arising from the continued excess of the

expenditure over the receipts of revenue for some years past. They

therefore recommended the reversal of the order of procedure, by

diminution of outlay, the increase of revenue, the gradual abolition of

notes, and the restraining of the issue of warrants to the amount

required yearly for the public service. They also alluded to the

advantages that would result from the establishment of a substantial

bank, issuing notes payable on demand, and affording other facilities

for the commercial and agricultural operations of the island. The

commissioners concluded their report by expressing their deliberate

opinion that whilst a paper circulation, based on adequate and available

capital, was, under prudent management, of the utmost benefit to a

commercial and agricultural population, and would contribute largely to

its prosperity, unconvertible paper was a curse and a deception,—a

delusive and fictitious capital, which left no solid foundation to rest

upon in any time of reverse and difficulty. They also expressed the hope

that on no pretext should a permanent debt be established in the colony,

as the evil effects of such a burden would not be confined to the

additional charge upon the revenue, but would necessitate the absorption

of capital which might be more beneficially employed in commerce,

manufactures, or agricultural improvement.

The subject of responsible government was discussed at length in the

assembly during the session of 1847, and an address to the Queen on the

subject was adopted by the house, in which it was represented that the

lieutenant-governor or administrator of the colony should be alone

responsible to the Queen and imperial parliament for his acts, that the

executive council should be deemed the constitutional advisers of the

representative of Her Majesty, and that when the acts of the

administrator of the government were such as the council could not

approve, they should be required to resign. The house recommended that

four members of the executive council should be selected from the lower

branch of the legislature, such members being held responsible to the

house for the acts of the administrator of the government. As the local

resources of the assembly did not admit of retiring pensions being

provided for the officers who might be affected by the introduction of

the system of departmental government, it was suggested that the

treasurer, colonial secretary, attorney general, and surveyor general

should not be required to resign, but that they should be required to

give a constitutional support to the measures of government. In closing

the session, the governor intimated his intention of giving the address

which had been voted by the house his cordial support.

As the governor’s term of office was about to expire, a petition was got

up by his friends, praying for his continuance in office. This movement

stimulated a counter movement on the part of an influential section of

the community, who were antagonistic to the governor, and, consequently,

a counter petition was framed, and a subscription set on foot to pay the

expenses of a deputation to convey the petition to England. The

deputation consisted of the following gentlemen: Mr. Joseph Pope,

speaker of the house of assembly, Mr. Edward Palmer, and Mr. Andrew

Duncan, a prominent merchant. The main grounds on which the continuance

in office of the governor was objected to were the following:—That he

had recently coalesced with parties who had been unremitting in their

endeavors to bring his person and government into contempt; that he had

shown a disinclination to advance the real interests of the colony, by

withdrawing his patronage and support from all public societies in the

island, because the legislature had declined to accede to his

application for an increase of salary from the public funds; that on one

occasion, through the colonial secretary, he publicly denounced every

member of society who would dare to partake of the hospitality of a

gentleman—a member of the legislative council—who was then politically

opposed to him; that he had, on various occasions, improperly exercised

the power given to him by the Queen, by appointing parties totally

unqualified by education and position to the magistracy; that on a late

occasion he had personally congratulated a successful political

candidate at government house, with illuminated windows, at a late hour

of the night, in presence of a large mob, who immediately after

proceeded through the town, and attacked the houses of several

unoffending inhabitants. This formidable catalogue of complaints was

calculated to produce a most unfavorable impression on the home

government, as to Sir Henry Vere Huntley’s competency to govern the

colony. But the home government had come to a determination on the

subject before the arrival of the deputation. “I regret to say,” wrote

Lord Grey, then the colonial secretary, addressing the governor on the

twelfth of August, “that having carefully reviewed your correspondence

with this office, I am of opinion that there is no special reason for

departing in your case from the ordinary rule of the colonial service,

and I shall, therefore, feel it my duty to recommend that you be

relieved in your government on the termination of the usual period for

which your office is held.”

Sir Donald Campbell, of Dunstaffnage, was appointed to take the place of

Governor Huntley. He arrived in Charlottetown early in December, and as

belonging to an ancient highland family, was greeted with more than

ordinary enthusiasm.

When in London, the speaker of the house of assembly and Mr. Palmer

called the attention of Earl Grey to the state of the currency, and his

lordship subsequently addressed a despatch to the lieutenant-governor on

the subject. He alluded to the practice of the local government issuing

treasury warrants for small sums of money, and treasury notes for still

smaller sums, for the purpose of meeting the ordinary expenses of the

government, as tending to depreciate the currency below its nominal

value. Two remedies presented themselves: first, whether it would be

proper to endeavor to restore this depreciated currency to its original

value; or, secondly, whether it would not be better to fix its value at

its present rate, taking the necessary measures for preventing its

further depreciation. He recommended the latter course, as more

injustice was usually done by restoring a depreciated currency to its

original value than by fixing it at the value which it might actually

bear. To prevent further depreciation, he recommended that the

legislature should pass a law enacting that the existing treasury

warrants should be exchanged for treasury notes to the same amount, and

that these notes should be declared a legal tender; that it should not

be lawful to make any further issue of treasury notes, except in

exchange for the precious metals, the coins of different countries being

taken at the value they bore in circulation, and that the treasury notes

should be made exchangeable at the pleasure of the holders for coin at

the same rate. In order to enable the colonial treasurer, or such other

officer as might be charged with the currency account, to meet any

demands which might be made upon him for coin in exchange for treasury

notes, it might be necessary to raise a moderate sum by loan, or

otherwise, for that purpose. Though these suggestions were not entirely

carried out, yet an act was passed in the session of 1849, which

determined the rates at which British and foreign coins were to be

current, and how debts contracted in the currency of the island were to

be payable.

The year 1848 was not remarkable for any historic event in the

island,—the taking of the census being the most noteworthy, when the

population was ascertained to be 62,634. But it was a most memorable

year in the history of Europe, for in that year Louis Philippe, the King

of the French, vacated the throne, and fled to England for protection,

an event which occasioned a general convulsion on the continent of

Europe.

The attention of the assembly was called to the evils which resulted

from elections taking place in the island on different days, which

presented an opportunity to the evil-disposed to attend in various

districts, and create a disturbance of the public peace. A measure was

accordingly introduced and passed, which provided for the elections

taking place in the various electoral districts on the same day,—an

antidote to disorder which has operated admirably, not only in Prince

Edward Island, but in all places where it has been adopted.

During summer, the governor—in order to become acquainted with the state

of the country—paid a visit to the various sections of the island, and

was well received. He was entertained at dinner by the highland society,

and the whole Celtic population rejoiced in the appointment of one of

their countrymen to the position of lieutenant-governor.

In January, 1849, a public meeting was held in Charlottetown, for the

purpose of forming a general union for the advancement of agricultural

pursuits. The chair was occupied by Sir Donald Campbell, and resolutions

were adopted, and a subscription begun to carry out the object of the

meeting.

Earl Grey transmitted a despatch to the governor in January, 1849,

stating the reasons why the government did not accede to the desire, so

generally expressed, to have responsible government introduced. He

stated that the introduction of the system had, in other cases, been

postponed until the gradual increase of the community in wealth,

numbers, and importance appeared to justify it. He referred to the

circumstance that Prince Edward Island was comparatively small in extent

and population, and its commercial and wealthy classes confined almost

entirely to a single town. While its people were distinguished by those

qualities of order and public spirit which formed the staple foundation

of all government, in as high a degree as any portion of their brethren

of British descent, yet the external circumstances which would render

the introduction of responsible government expedient were

wanting,—circumstances of which time, and the natural progress of

events, could alone remove the deficiency. For these reasons Earl Grey

concurred with his predecessor, Mr. Gladstone, that the time for a

change had not yet arrived. He, at the same time, expressed his

conviction that the existing system of administration was compatible

with the complete enjoyment by the inhabitants of the colony of the real

benefits of self-government.

The colonial secretary thought that the period had come when the

assembly of the island should undertake to provide for the civil list.

He accordingly addressed a despatch to the governor, intimating that the

home government was willing to provide the salary of the governor, which

it proposed to increase to fifteen hundred pounds sterling a year,

provided the other expenses of the civil government were defrayed from

the funds of the island. To this proposal the house expressed its

willingness to accede, provided that all revenues arising from the

permanent revenue laws of the colony were granted in perpetuity, all

claim to the quitrents and crown lands abandoned, and a system of

responsible government conceded. The home government, in reply,

expressed its willingness to accede to the wishes of the assembly on all

these points, with trifling modifications, save the granting of

responsible government, in the present circumstances of the island. The

governor, therefore, deemed it the best course to dissolve the assembly

and convene a new one, which met on the fifth of March, 1850. In the

reply to the governor’s speech, the assembly inserted a paragraph, in

which want of confidence in the executive council was emphatically

expressed. Mr. Coles also moved a resolution in the house, embodying the

reasons of the assembly for its want of confidence, and refusing to

grant supplies till the government should be remodelled, or in other

words, responsible government conceded. The governor proposed to meet

the views of the house so far, on his own responsibility, as to admit

into the executive council three gentlemen possessing its confidence in

room of three junior members of the council. This proposal was not

deemed acceptable. The house then adopted an address to the Queen, in

which its views were set forth. The house contended that, in taking

measures to secure responsible government, the governor would be only

acting in accordance with the spirit of his instructions, and that as

all the members of the executive council had resigned, there was no

impediment to the introduction of the desired change. The house was

prorogued on the twenty-sixth of March, but again summoned on the

twenty-fifth of April. Whilst the house granted certain limited

supplies, it refused to proceed to the transaction of the other business

to which its attention was called in the governor’s opening speech. No

provision was made for the roads and bridges, and other services, and

the governor, in his answer to the address of the house in reply to his

closing speech, said: “I should fail in the performance of my duty, if I

did not express my disapprobation of your premeditated neglect of your

legislative functions.”

The governor transmitted an able despatch to the colonial secretary, in

1849, on the resources of the island, which Lord Grey appreciated

highly; but the career of the baronet as a governor was destined to be

of short duration, for he died in October of the following year, at the

comparatively early age of fifty years. In Sir Donald Campbell were

united some of the best qualities of a good governor. He was firm and

faithful in the discharge of duty; at the same time of a conciliatory

and kindly disposition.

The Honorable Ambrose Lane, who had been formerly administrator during

Governor Huntley’s temporary absence, was again appointed to that office

till the arrival of Sir A. Bannerman, the new lieutenant-governor. His

excellency arrived at Charlottetown on the eighth of March, having

crossed the strait in the ice-boat. The legislature assembled on the

twenty-fifth of March, 1851. In the opening speech the governor informed

the house that responsible government would be granted on condition of

compensation being allowed to certain retiring officers. The house

acceded to the proposal, and a new government—sustained by a majority of

the assembly—was accordingly formed in April,—the leaders being the

Honorable George Coles, president, and the Honorable Charles Young,

attorney general. The Honorable Joseph Pope was appointed to the

treasurer-ship, and the Honorable James Warburton to the office of

colonial secretary. Besides an important act to commute the Crown

revenues of the island, and to provide for the civil list in accordance

with the suggestions of the home government, a measure was in this year

passed for the transference of the management of the inland posts, and

making threepence the postage of ordinary letters to any part of British

America, and a uniform rate of twopence to any part of the island. This

year was also memorable in the annals of the island, in consequence of a

violent storm which swept over it on the third and fourth of October, by

which seventy-two American fishing vessels were seriously damaged or

cast ashore.

The governor, in opening the session of 1852, stated that he had much

pleasure in visiting many parts of the island; but that he observed with

regret the educational deficiency which still existed, and which the

government would endeavor to assist in supplying, by introducing a

measure which, he hoped, would receive the approval of the house. An act

for the encouragement of education, and to raise funds for that purpose

by imposing an additional assessment on land, was accordingly passed,

which formed the basis of the present educational system.

In April, 1853, the Honorable Charles Young and Captain Swabey—the

former attorney general, and the latter registrar of deeds and chairman

of the Board of Education—resigned their seats as members of the

executive council. Mr. Joseph Hensley was appointed to the office of

attorney general, and Mr. John Longworth to that of solicitor general,

in place of Mr. Hensley. Mr. Young’s resignation was mainly owing to the

approval, by a majority of his colleagues in the government, of an act

to regulate the salaries of the attorney general and solicitor general,

and clerk of the Crown and prothonotary, for their services, to which he

and other members of the government had serious objections, which they

embodied in a protest on the passing of the bill.

The temperance organizations in the island were particularly active at

the period at which we have arrived. A meeting was held in

Charlottetown, for the purpose of discussing the propriety and

practicability of abolishing by law the manufacture and sale of

intoxicating liquors. There would be consistency in prohibiting the

manufacture and importation of intoxicating liquors, as well as the sale

of them. But the Maine law, which permits the importation of liquor into

the state, whilst it prohibits its sale, is a useless anomaly. Let

anyone visit Portland—where he might expect to see the law decently

enforced—and he will find in one, at least, of the principal hotels in

the city, a public bar-room in which alcoholic liquors of all kinds are

openly sold; and, if he chooses to begin business in the liquor line, he

can, for thirty dollars, procure a license from one of the officials of

the United States government, for that purpose. The United States law

sanctions the importation and sale of intoxicating drinks; the Maine

state law forbids the sale ostensibly, whilst it is really permitted.

The temperance movement has effected a vast amount of good, but coercion

is not the means by which it has been accomplished.

During the session of 1853, an act to extend the elective franchise was

passed, which made that privilege almost universal. The house was

dissolved during the summer, and at the general election which ensued

the government was defeated. A requisition was in consequence addressed

to the governor by members of the assembly, praying for the early

assembling of the house, in order that, by legal enactment, departmental

officers might be excluded from occupying seats in the legislature, to

which request the governor did not accede.

On the seventh of October, 1853, a sad catastrophe took place in the

loss of the steamer Fairy Queen. The boat left Charlottetown on a

Friday forenoon. Shortly after getting clear of Point Prim, the vessel

shipped a sea which broke open the gangways. When near Pictou Island the

tiller-rope broke, and another heavy sea was shipped. The rope was, with

the assistance of some of the passengers, spliced; but the vessel moved

very slowly. The captain and some of the crew got into a boat and

drifted away, regardless of the fate of the female passengers. Among the

passengers were Mr. Martin I. Wilkins, of Pictou, Mr. Lydiard, Mr.

Pineo, Dr. McKenzie, and others. After having been subjected to a series

of heavy seas, the upper deck, abaft the funnel, separated from the main

body of the vessel, and providentially constituted an admirable raft, by

which a number of the passengers were saved, among whom were Messrs.

Wilkins, Lydiard, and Pineo, who landed on the north side of Merigomish

Island, after eight hours of exposure to the storm and cold. Dr.

McKenzie,—an excellent young man,—other two males, and four females

perished.

In opening the assembly of 1854, the governor referred in terms of

congratulation to the prosperous state of the revenue. On the

thirty-first of January, 1850, the balance of debt against the colony

was twenty-eight thousand pounds. In four years it was reduced to three

thousand pounds. The revenue had increased from twenty-two thousand

pounds, in 1850, to thirty-five thousand in 1853, notwithstanding a

reduction in the duty on tea, and two thousand eight hundred pounds

assessment imposed for educational purposes.

The new house having declared its want of confidence in the government,

a new one was formed, of which the leaders were the Honorables J. M.

Holl and Edward Palmer; but there was a majority opposed to it in the

upper branch, which, to some extent, frustrated the satisfactory working

of the machine. The house was prorogued in May; and, in opposition to

the unanimous opinion of his council, the governor dissolved the

assembly,—the reason assigned for this course of procedure being, that

the act passed for the extension of the franchise had received the royal

assent, and that for the interest of the country it was necessary to

have a house based on the new law. An appeal to the country was certain

to ensure the defeat of the government; and the governor was accused of

desiring to effect that object before his departure from the island,—for

he had been appointed to the government of the Bahamas. It is only due

to Governor Bannerman to state that he had anticipated difficulties,

which constrained him to consult the colonial secretary as to the most

proper course of action, and that he received a despatch, in which the

duke said: “I leave it with yourself, with full confidence in your

judgment, to take such steps in relation to the executive council and

the assembly as you may think proper before leaving the government.” We

may be permitted to say that it is only in very rare and exceptional

cases that either a British sovereign or a royal representative can be

justified in disregarding the advice of constitutional advisers; and the

case under notice does not seem, in any of its bearings, to have been

one in relation to which the prerogative should have been exercised.

Dominick Daly, Esq., succeeded Governor Bannerman, and arrived on the

island on the twelfth of June, 1854, and was received by all classes

with much cordiality: addresses poured in upon his excellency from all

parts of the island. A few days after the arrival of the new governor

the election took place, and was, as anticipated, unfavorable to the

government, which, to its credit, resigned on the twentieth of

July,—intimation to that effect having been communicated to the governor

by the president of the executive council, John M. Holl. A new

government was formed, and the house assembled in September, in

consequence of the ratification of a commercial treaty between the

British and United States governments, and the withdrawal of the troops

from the island,—circumstances which required the immediate

consideration of the assembly. The session was a short one, the

attention of the house being directed exclusively to the business for

the transaction of which it had met. An act was immediately passed to

authorise free trade with the United States, under the treaty which had

been concluded. The measure opened the way for the introduction into the

island, free of duty, of grain and breadstuffs of all kinds; butter,

cheese, tallow, lard, etc., in accordance with a policy which has been

found to operate most beneficially in the countries where it has been

adopted. Great Britain declared war in this year against Russia; but,

beyond the withdrawal of the troops and the advance of the prices of

breadstuffs and provisions, the island was not affected by its

prosecution.

The Worrell Estate, consisting of eighty-one thousand three hundred and

three acres, was purchased by the government at the close of the year

1854,—the price paid for the property being twenty-four thousand one

hundred pounds, of which eighteen thousand pounds were paid down, and

the balance retained till the accuracy of its declared extent was

ascertained.

In the session of 1855 a considerable amount of legislative business was

transacted, including the passing of an act for the incorporation of

Charlottetown, an act for the incorporation of the Bank of Prince Edward

Island, and an act to provide a normal school for the training of

teachers. In proroguing the assembly, the governor referred in terms of

condemnation to any further agitation of the question of escheat, as

successive governments were opposed to every measure which had hitherto

passed relating to the subject, in the wisdom of which opposition the

governor expressed himself as fully concurring. He approved of the

active measures which had been taken under the Land Purchase Bill, and

expressed his conviction that similar measures only required the cordial

co-operation of the tenantry to secure an amount of advantage to

themselves which no degree of agitation could obtain. The island had

contributed two thousand pounds to the Patriotic Fund, which had been

instituted to relieve the widows and children of soldiers who fell in

the Crimean war; and the governor expressed Her Majesty’s satisfaction

with the generous sympathy thus evinced by the people and their

representatives.

In the month of March, 1855, a distressing occurrence took place. The

ice-boat from Cape Tormentine to the island, with Mr. James Henry

Haszard, Mr. Johnson, son of Dr. Johnson, medical students, and an old

gentleman—Mr. Joseph Weir, of Bangor—as passengers, had proceeded safely

to within half a mile of the island shore, when a severe snow-storm was

encountered. The boat, utterly unable to make headway, was put about,

drawn on the ice, and turned up to protect the men from the cold and

fury of the storm. Thus they were drifted helplessly in the strait

during Friday night, Saturday, and Saturday night. On Sunday morning

they began to drag the boat towards the mainland, and, exhausted,—not

having tasted food for three days,—they were about ceasing all further

efforts, when they resolved to kill a spaniel which Mr. Weir had with

him, and the poor fellows drank the blood and eat the raw flesh of the

animal. They now felt a little revived, and lightened the boat by

throwing out trunks and baggage. Mr. Haszard was put into the boat,

being unable to walk; and thus they moved towards the shore, from which

they were four or five miles distant. On Monday evening Mr. Haszard died

from exhaustion. They toiled on, however, and on Tuesday morning reached

the shore, near Wallace, Nova Scotia, but, unfortunately, at a point two

miles from the nearest dwelling. Two of the boatmen succeeded in

reaching a house, and all the survivors, though much frost-bitten,

recovered under the kind and judicious treatment which they received.

The census taken in 1855 declared the population of the island to be

seventy-one thousand. There were two hundred and sixty-eight schools,

attended by eleven thousand pupils. The Normal School was opened in 1856

by the governor, and constituted an important addition to the

educational machinery of the island.

During the session of 1855 an act was passed to impose a rate or duty on

the rent-rolls of the proprietors of certain rented township-lands, and

also an act to secure compensation to tenants; but the governor

intimated, in opening the assembly in 1856, that both acts had not

received Her Majesty’s confirmation, at which, in their reply to the

speech, the house expressed regret,—not hesitating to tell His

Excellency that they believed their rejection was attributable to the

influence of non-resident proprietors, which had dominated so long in

the councils of the Sovereign. Mr. Labouchere, the colonial secretary,

in intimating the decision of the government in reference to the acts

specified, stated that whatever character might properly attach to the

circumstances connected with the original grants, which had been often

employed against the maintenance of the rights of the proprietors, they

could not, with justice, be used to defeat the rights of the present

owners, who had acquired their property by inheritance, by family

settlement, or otherwise. Seeing, therefore, that the rights of the

proprietors could not be sacrificed without manifest injustice, he felt

it his duty steadily to resist, by all means in his power, measures

similar in their character to those recently brought under the

consideration of Her Majesty’s government. He desired, at the same,

time, to assure the house of assembly that it was with much regret that

Her Majesty’s advisers felt themselves constrained to oppose the wishes

of the people of Prince Edward Island, and that it was his own wish to

be spared the necessity of authoritative interference in regard to

matters affecting the internal administration of their affairs.

With regard to the main object which had been frequently proposed by a

large portion of the inhabitants, namely, that some means might be

provided by which a tenant holding under a lease could arrive at the

position of a fee-simple proprietor, he was anxious to facilitate such a

change, provided it could be effected without injustice to the

proprietors. Two ways suggested themselves: first, the usual and natural

one of purchase and sale between the tenant and the owner; and,

secondly, that the government of the island should treat with such of

the landowners as might be willing to sell, and that the state, thus

becoming possessed of the fee-simple of such lands as might thus be

sold, should be enabled to afford greater facilities for converting the

tenants into freeholders. Such an arrangement could not probably be made

without a loan, to be raised by the island government, the interest of

which would be charged upon the revenues of the island. Mr. Labouchere

intimated that the government would not be indisposed to take into

consideration any plan of this kind which might be submitted to them,

showing in what way the interest of such loan could locally be provided

for, and what arrangements would be proposed as to the manner of

disposing of the lands of which the fee-simple was intended to be

bought.

In 1856 the legislature presented an address to the Queen, suggesting

the guaranty of a loan for the purchase of township lands, with a view

to the more speedy and general conversion of leaseholds into freehold

tenures. In answering this address, the colonial secretary intimated

that the documents sent to him appeared to Her Majesty’s government to

afford a sufficient guaranty for the due payment of the interest, and

for the formation of a sinking-fund for the payment of the principal of

the loan; and that they were prepared to authorise a loan of one hundred

thousand pounds, sterling, to be appropriated, on certain specified

conditions, to the purchase of the rights of landed proprietors in the

island. It will be afterwards seen that good faith was not kept with the

people of the island in this matter.

The question as to whether the Bible ought to be made a text-book in the

public schools of the island had been freely discussed since the opening

of the Normal School, in October, 1856, when the discussion arose in

consequence of remarks made by Mr. Stark, the inspector of schools.

Petitions praying for the introduction of the Bible into the Central

Academy and the Normal School were presented at the commencement of the

session of 1858, and the question came before the house on the

nineteenth of March, when Mr. McGill, as chairman of the committee on

certain petitions relating to the subject, reported that the committee

adopted a resolution to the effect that it was inexpedient to comply

with the prayer of the several petitions before the house asking for an

act of the legislature to compel the use of the protestant Bible as a

class-book in mixed schools like the Central Academy and Normal School,

which were supported by protestants and catholics alike,—the house

feeling assured that so unjust and so unnecessary a measure was neither

desired by a majority of the inhabitants of the colony, nor essential to

the encouragement of education and religion. The Honorable Mr. Palmer

moved an amendment, to the effect that it was necessary to provide by

law that the holy Scriptures might be read and used by any scholar or

scholars attending either the Central Academy or Normal School, in all

cases where the parents or guardians might require the same to be used.

The house then divided on the motion of amendment, when the numbers were

found equal; but the speaker gave his casting vote in the negative. Mr.

McGill being one of the prominent public men opposed to the principle of

compulsion in religious matters, was at this time subjected to much

unmerited abuse, emanating from quarters where the cultivation of a

better spirit might be reasonably expected.

The quadrennial election took place in June, 1858, when the strength of

the government was reduced to such a degree as to render the successful

conduct of the public business impossible. The government dismissed the

postmaster and some of his subordinates from office, which occasioned a

large county meeting in Charlottetown, at which resolutions condemnatory

of the action of the government and expressive of sympathy for and

confidence in the ability and fidelity of the officials were passed. The

principal speakers were Mr. William McNeill, Colonel Gray, Honorable E.

Palmer, and W. H. Hyde. When the house met, it was found that parties

were so closely balanced that the business of the country could not be

transacted on the basis of the policy of the government or opposition.

The house failed to elect a speaker,—the parties nominated having

refused to accept office in the event of election. A dissolution

consequently took place, and a new election was ordered. The contest at

the polls resulted in the defeat of the government, who resigned on the

fourth of April, and a new government was formed, of which the leaders

were the Honorable Edward Palmer and the Honorable Colonel Gray.

On the morning that the Islander published the names of the new

government, it also announced the death of Duncan McLean, who for nine

years edited that paper, and who had, just before his death, been

appointed Commissioner of Public Lands. Mr. McLean was a well-informed

and vigorous writer; and, although his pen was not unfrequently dipped

in political gall, yet he was genial and kindly in private life, and was

a man who never nourished his wrath to keep it warm, or allowed it to

extend beyond the political arena. Mr. McLean had a large circle of

friends who deeply regretted his death.

The governor, in the opening speech of the session, intimated that he

had received communications from Her Majesty’s government on the subject

of a federal union of the North American Provinces. He also stated that

it was not the intention of the home government to propose to parliament

the guaranteeing of the contemplated loan. He also informed the house

that he had some time previously tendered his resignation of the

lieutenant-governorship of the island, that his services were to be

employed in another portion of the colonial possessions, and that his

successor had been appointed.

Colonel Gray submitted to the house a series of resolutions, which were

adopted with certain modifications, praying that Her Majesty would be

pleased to direct a commission to some discreet and impartial person,

not connected with the island or its affairs, to inquire into the

existing relations of landlord and tenant, and to negotiate with the

proprietors for such an abatement of present liabilities, and for such

terms for enabling the tenantry to convert their leaseholds into

freeholds as might be fairly asked to ameliorate the condition of the

tenantry. It was suggested in these resolutions that the basis of any

such arrangement should be a large remission of arrears of rent now due,

and the giving every tenant holding under a long lease the option of

purchasing his land at a certain rate at any time he might find it

convenient to do so.

The legislative council, of which the Honorable Charles Young, LL. D.,

was president, adopted an address praying that the Queen would be

pleased to give instructions that an administration might be formed in

consonance with the royal instructions when assent was given to the

Civil List Bill, passed in April, 1857. The council complained that the

principle of responsible government was violated in the construction of

the existing executive council, which did not contain one Roman

catholic, though the population of that faith was, according to the

census of 1855, thirty-two thousand; that not one member of the

legislative council belonged to the executive; that persons were

appointed to all the departmental offices who had no seats in the

legislature, and who were, in consequence, in no way responsible to the

people; and as all persons accepting office under the Crown, when

members of the assembly, were compelled to appeal to their constituents

for re-election, this statute was deliberately evaded, and no

parliamentary responsibility existed.

In replying to the address of the legislative council, in a

counter-address, the house of assembly contended that there was no

violation of the principle of the act passed in 1857; that the

prejudicial influence of salaried officers having seats in the assembly

was condemned by the people at the polls, as indicated by the present

house, where there were nineteen for, to eleven members opposed to the

principle. As evidence of public opinion on the subject, it was further

stated, that when the commissioner of public lands, after accepting

office in the year 1857, appealed to the people, he was rejected by a

large majority; that the attorney general and registrar of deeds, at the

general election in June last, were in like manner rejected; and that at

the general election in March last, the treasurer and postmaster-general

were also rejected,—the colonial secretary being the only departmental

officer who was able to procure a constituency.

On the nineteenth of May, Lieut. Governor Daly prorogued the house in a

graceful speech. He said he could not permit the last opportunity to

pass without expressing the gratification which he should ever

experience in the recollection of the harmony which had subsisted

between the executive and the other branches of the legislature during

the whole course of his administration, to which the uninterrupted

tranquillity of the island during the same period might in a great

measure be attributed. The performance of the important and often

anxious duties attached to his station had been facilitated and

alleviated by the confidence which they had ever so frankly reposed in

the sincerity of his desire to promote the welfare of the community; and

notwithstanding the peculiar evils with which the colony had to contend,

he had the satisfaction of witnessing the triumph of its natural

resources in its steady though limited improvement. In bidding the house

and the people farewell, he trusted that the favor of Divine Providence,

which had been so signally manifested towards the island, might ever be

continued to it, and conduct its inhabitants to the condition of

prosperity and improvement which was ever attainable by the united and

harmonious cultivation of such capabilities as were possessed by Prince

Edward Island.

Sir Dominick Daly having left the island in May, the Honorable Charles

Young, president of the legislative council, was sworn in as

administrator. Mr. George Dundas, member of parliament for

Linlithgowshire, was appointed lieutenant-governor, and arrived in June,

when he received a cordial welcome. Amongst the numerous addresses

presented to the governor was one from the ministers of the Wesleyan

Conference of Eastern British America, assembled in Charlottetown, who

represented a ministry of upwards of a hundred, and a church-membership

of about fifteen thousand.

General Williams, the hero of Kars, visited the island in July, and

received a hearty welcome from all classes. He was entertained at supper

served in the Province Building. The Mayor of Charlottetown, the

Honorable T. H. Haviland, occupied the chair, having on his right hand

Mrs. Dundas and General Williams, and on his left, Mrs. E. Palmer and

the Lieutenant-governor. The Honorable Mr. Coles acted as croupier.

On the thirtieth of December, 1859, at Saint Dunstan’s College, died the

Right Reverend Bernard Donald McDonald, Roman catholic bishop of the

island. He was a native of the island, having been born in the parish of

Saint Andrew’s in December, 1797. He obtained the rudiments of an

English education in the school of his native district,—one of the very

first educational establishments then existing on the island. He

entered, at the age of fifteen, his alma mater,—the Seminary of

Quebec. Here he remained for ten years, during which time he

distinguished himself by his unremitting application to study, and a

virtuous life. It was then that he laid the foundation of that fund of

varied and extensive learning—both sacred and profane—which rendered his

conversation on every subject agreeable, interesting, and instructive.

Having completed his studies, he was ordained priest in the spring of

1824, and he soon afterwards entered on his missionary career. There

being but few clergymen on the island at that time, he had to take

charge of all the western parishes, including Indian River, Grand River,

Miscouche, Fifteen Point, Belle Alliance, Cascumpec, Tignish, etc. In

all these missions he succeeded, by his zeal and untiring energy, in

building churches and parochial houses. In the autumn of 1829 he was

appointed pastor of Charlottetown and the neighboring missions. In 1836

he was nominated by the Pope successor to the Right Reverend Bishop

MacEachern, and on the fifteenth of October of that year was consecrated

Bishop of Charlottetown in Saint Patrick’s Church, Quebec.

The deceased prelate was charitable, hospitable, and pious. Having few

priests in his diocese, he himself took charge of a mission; and besides

attending to all his episcopal functions, he also discharged the duties

of a parish priest. He took a deep interest in the promotion of

education. He established in his own district schools in which the young

might be instructed, not only in secular knowledge, but also in their

moral and religious duties, and encouraged as much as possible their

establishment throughout the whole extent of his diocese. Aided by the

co-operation of the charitable and by the munificent donation of a

gentleman, now living, he was enabled to establish in Charlottetown a

convent of ladies of the Congregation de Notre Dame,—which institution

is now in a flourishing condition, affording to numerous young ladies,

belonging to Charlottetown and other parts of the island, the

inestimable blessing of a superior education. But the educational

establishment in which the bishop appeared to take the principal

interest was Saint Dunstan’s College. This institution, which is an

ornament to the island, the lamented bishop opened early in 1855. The

care with which he watched over its progress and provided for its wants,

until the time of his death, was truly paternal. Long before he

departed, he had the satisfaction of seeing the institution established

on a firm basis and in a prosperous condition.

In the year 1856 the bishop contracted a cough, and declining health

soon became perceptible. He, however, continued to discharge his duties

as pastor of Saint Augustine’s Church, Rustico, until the autumn of

1857, when, by medical advice, he discontinued the most laborious

portion of them. Finding that his disease—chronic bronchitis—was

becoming more deeply seated, he went to New York in the summer of 1858,

and consulted the most eminent physicians of that city, but to little or

no purpose. His health continuing to decline, he set his house in order,

and awaited the time of his dissolution with the utmost resignation.

About two months before his death he removed from Rustico, and took up

his residence in Saint Dunstan’s College, saying that he wished to die

within its walls. On the twenty-second of December he became visibly

worse, and on the twenty-sixth he received the last sacraments. He

continued to linger till the thirtieth, when he calmly expired, in the

sixty-second year of his age.

The lieutenant-governor was instructed by the home government that, in

the event of the absence of harmony between the legislative council and

the assembly, he should increase the number of councillors, and thus

facilitate the movements of the machine. Five additional members were

accordingly added to the council. During the session, several acts were

passed relating to education, including one which provided for the

establishment of the Prince of Wales College.

The governor laid before the house a despatch, which he had received

from the colonial secretary, the Duke of Newcastle, relative to the

subject of the proposed commission on the land question. His grace had

received a letter, signed by Sir Samuel Cunard and other proprietors, in

which, addressing his grace, they said: “We have been furnished with a

copy of a memorial, addressed to Her Majesty, from the house of assembly

of Prince Edward Island, on the questions which have arisen in

connection with the original grants of land in that island, and the

rights of proprietors in respect thereof. We observe that the assembly

have suggested that Her Majesty should appoint one or more commissioners

to inquire into the relations of landlord and tenant in the island, and

to negotiate with the proprietors of the township lands, for fixing a

certain rate of price at which every tenant might have the option of

purchasing his land; and, also, to negotiate with the proprietors for a

remission of the arrears of rent in such cases as the commissioners

might deem reasonable; and proposing that the commissioners should

report the result to Her Majesty. As large proprietors in this island,

we beg to state that we shall acquiesce in any arrangement that may be

practicable for the purpose of settling the various questions alluded to

in the memorial of the house of assembly; but we do not think that the

appointment of commissioners, in the manner proposed by them, would be

the most desirable mode of procedure, as the labors of such

commissioners would only terminate in a report, which would not be

binding on any of the parties interested. We beg, therefore, to suggest

that, instead of the mode proposed by the assembly, three commissioners

or referees should be appointed,—one to be named by Her Majesty, one by

the house of assembly, and one by the proprietors of the land,—and that

these commissioners should have power to enter into all the inquiries

that may be necessary, and to decide upon the different questions which

may be brought before them, giving, of course, to the parties interested

an opportunity of being heard. We should propose that the expense of the

commission should be paid by the three parties to the reference, that is

to say, in equal thirds; and we feel assured that there would be no

difficulty in securing the adherence of all the landed proprietors to a

settlement on this footing. The precise mode of carrying it into

execution, if adopted, would require consideration, and upon that

subject we trust that your grace will lend your valuable assistance.

“If the consent,” said the colonial secretary, “of all the parties can

be obtained to this proposal, I believe that it may offer the means of

bringing these long pending disputes to a termination. But it will be

necessary, before going further into the matter, to be assured that the

tenants will accept as binding the decision of the commissioners, or the

majority of them; and, as far as possible, that the legislature of the

colony would concur in any measures which might be required to give

validity to that decision. It would be very desirable, also, that any

commissioner who might be named by the house of assembly, on behalf of

the tenants, should go into the inquiry unfettered by any conditions

such as were proposed in the assembly last year.”

The proposal of the colonial secretary, as to the land commission, came

formally before the house on the thirteenth of April, when Colonel Gray

moved that the house deemed it expedient to concur in the suggestions

offered for their consideration for the arrangement of the long pending

dispute between the landlords and tenants of the island, and, therefore,

agreed to the appointment of three commissioners,—one by Her Majesty,

one by the house of assembly, and the third by the proprietors,—the

expense to be divided equally between the imperial government, the

general revenue of the colony, and the proprietors; and that the house

also agreed, on the part of the tenantry, to abide by the decision of

the commissioners, or the majority of them, and pledged themselves to

concur in whatever measures might be required to give validity to that

decision. Mr. Coles proposed an amendment, to the effect that there were

no means of ascertaining the views and opinions of the tenantry upon the

questions at issue, unless by an appeal to the whole people of the

colony, in the usual constitutional manner, and that any decision

otherwise come to by the commissioners or referees appointed should not

be regarded as binding on the tenantry. On a division, the motion of

Colonel Gray was carried by nineteen to nine. It was then moved by Mr.

Howat, that the Honorable Joseph Howe, of Nova Scotia, should be the

commissioner for the tenantry, which was unanimously agreed to.

During this session, that of 1860, the assembly agreed to purchase the

extensive estates of the Earl of Selkirk; and the purchase of sixty-two

thousand and fifty-nine acres was effected, at the very moderate rate of

six thousand five hundred and eighty-six pounds sterling,—thus enabling

the government to offer to industrious tenants facilities for becoming

the owners of land which was then held by them on lease.

On the fourth of May, 1860, died Mr. James Peake, at Plymouth, England.

From the year 1823 until 1856, Mr. Peake was actively engaged in

mercantile pursuits on the island. He was a successful merchant, and for

some years held a seat in Her Majesty’s executive council. Of a kind

find generous disposition, he did not live to himself, but was ever

ready to extend a helping hand to industrious and reliable persons, who

might need aid and encouragement. He was highly esteemed as a liberal,

honorable man. His integrity and enterprise placed him in the front rank

as a merchant. “None,” said the Islander, “was more deservedly

respected, and by his death the world has lost one who was an honest and

upright man.” |