|

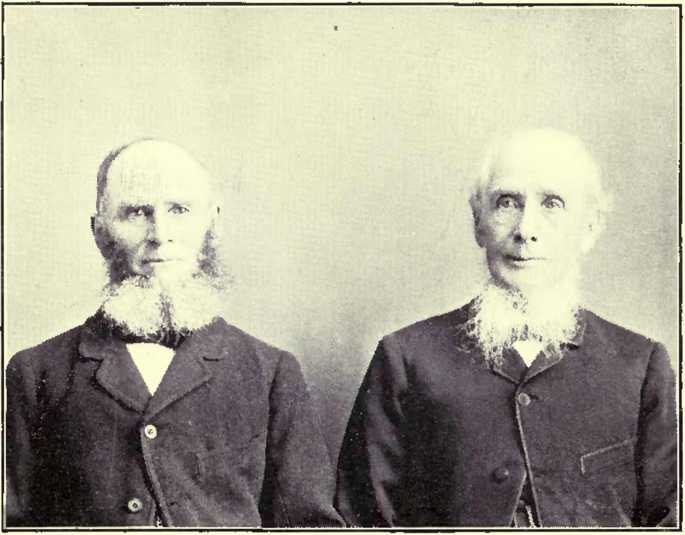

JAMES GUNNNG BROTHERS

WILLIAM

IN the south-west of

England, along the southern shore of the Bristol Channel, lies

Somersetshire, one of the most beautiful counties in that beautiful

land—fertile, nearly all pasturable, and its climate soft and equable.

The great plain of which it is composed is throughout the whole year a

spot of surpassing beauty. The rose of England here blooms the fairest,

and in the sequestered groves that deck the gentle -slopes of the Mendip

Hills, the nightingale, in harmony with the beautiful in nature, at

eventide pours out to the gathering shades of night her ever-delightful

song. Like nearly every corner of England, Somerset has historical

associations. On the west, and near the banks of the Severn, stand the

remains of the Abbey of Glastonbury. The vastness of the crumbling

arches conveys in impressive silence to the tourist some idea of its

grandeur at that period when the Church that laid its foundations was

the Church of the world. Its long drawn aisles, its cloisters, its

sacred altars, have long since been stripped of their glory and sunk in

ruin and decay. The columns that supported the roof of the great edifice

are broken and fallen, and the most splendid efforts of human invention

and magnificent work of human hands fill its holy places in mockery of

the greatest achievements of men. The tongue of the great bell, that

called the people to vespers as evening crept on in quietness and

repose, speaks from the old tower no more. The tramp of the holy men,

the acolytes, the chant of the sacred ceremony of the Mass, will never

be heard again among these crumbling arches that seem to wait in silence

the inevitable hour when they will topple over to increase the mass of

rubbish at their base. Time, the great worker, while he has placed his

destroying finger on those magnificent pieces of art, and thrown them

again to earth, has to some extent repaired the work of his relentless

hands by the profusion of flowers he has scattered everywhere. The

vagrant flocks now browse peacefully in the halls of that splendid

temple, or recline at noon-day in the shadow of its ruined walls. The

lover of the beautiful must ever regret that the fanaticism of the

reformers at that period of the Reformation should have led them on to

destroy even the very symbols of the Church’s greatness. But the human

mind is a strange and complex machine, its actions being governed, in

almost all cases, rather by an association of ideas than abstract

principles. The Church had in the lapse of ages grown to immense power.

This power had given birth to intolerance and arrogance. She had won for

herself the highest place on earth. In that great unknown future she

reached out her strong arm and opened or shut the doors of hell, and in

her ineffable majesty rolled back or closed the gates of heaven.

In the centre of the

shire, and south of the Mendip Hills, is the dreary waste of Sedgemoor.

Here was fought the memorable battle between the unfortunate Duke of

Monmouth and James II. This noble and generous-hearted man commanded

James’s army against the Covenanters at their last final struggle at

Bothwell Brig, where the Covenanters were completely cut to pieces. At

the termination of that conflict, the Duke issued orders to spare the

lives of all the poor people who were taken prisoners. Such orders were

lost on such men as Dalzill, Johnston, or the cruel and bloody

Claverhouse, who with the spirit of demons butchered in cold blood the

men who were in arms for freedom and liberty of conscience. Subsequently

the Duke, at the instigation of the Whigs of England, raised the

standard of rebellion at Sedgemoor against the despotic government of

James, where his army was defeated and he was found next morning hid

among the reeds in a ditch on the battle-field. For his part in this

affair he was moved to London and beheaded.

Such are the historical

associations connected with Somersetshire, where, near the little town

of Shipton-Mallet, were born the subjects of our sketch,—William, on the

27th day of October, 1820, and James, on the 12th day of November, 1831.

As the lives of the two brothers have been so closely associated since

they came to Canada, we will proceed in the first part of this sketch

with the life of William, who at the present time resides on lot 3,

concession 12, Blanshard.

WILLIAM GUNNING

William Gunning was the

son of a small farmer, but who, in connection with his small holding,

carried on the business of burning lime. Like the ancestors of nearly

all the pioneers of Blanshard, he was not blessed with a large share of

this world’s goods, and had a constant struggle to maintain out of his

small earnings his wife and family. Like almost all of the poor people

in the Old Country, he was anxious that his family should receive such

education as would fit them for the ordinary duties of active life.

Accordingly the subject of our sketch was sent to school in Shipton-Mallet,

where he remained, with the exception of such periods as his assistance

was required on the farm, till he was fifteen years of age. As some of

the younger brothers were then able to assist in the farm work, William

was bound as an apprentice to a cabinet-maker for five years. For this

five years of labor he, as was the custom at that time, received little

or no remuneration. He continued to work at his trade for a few years,

when, in 1842, his father died, his mother having also died in 1837. As

the oldest of the family, he returned to his home and assumed the

management of his father’s business; but the laborious nature of the

occupation and the small returns for his exertion soon led him to try

some other field for his activity and energy. He therefore made

arrangement for the care of his brothers and sisters, and on the first

day of April, 1843, he left Bristol for America, determined to push his

fortune in the West. After a passage of five weeks and four days he

arrived at New York. But lie had no idea of becoming a subject of Uncle

Sam. He was a true Englishman, and thought then, as he does yet, that

there is no country like the country of his birth. He stayed only a

short time in New York, when he came to Oswego, crossed Lake Ontario in

the steamer Lady of the Lake, and came to Toronto. Here he felt at home

once more when he saw the flag of his country floating over the city,

and in Canada he decided to remain. He sought and obtained work with a

carpenter in Yorkville, named Mr. White, and who was an uncle of Wm. and

Geo. White, of the tenth concession of Blanshard, and, I believe, of Mr.

White, of White & May, St. Marys. With Mr. White Mr. Gunning worked for

one year, when he removed to Chippawa, on the Niagara frontier, where he

resumed his trade of cabinet-making and running an engine. He again left

Chippawa and worked with a farmer at Queenston Heights, the first

farming he had ever done in Canada. He had married at the age of 22 a

lady in England, and who died shortly after he came to Canada in

Yorkville, Toronto. In the fall of 1845 he again left Canada and went to

England, where, on the 27th day of January, 1846, he married Miss Sarah

Savior. This lady is a kind, industrious woman, and nobly assisted him

in all the trials and hardships attending pioneer life. She was a good

mother and infused into her family so much of her own love and affection

that at the present time they are noted for their consideration for and

abiding pleasure in the company of one another. To Mr. and Mrs. Gunning

there were born eleven children—Samuel, living in Blanshard; Thomas, who

died in 1881; Eliza (Mrs. John Parkinson), of Blanshard; Albert, on the

homestead; Emily (Mrs. Heron), of Exeter; Louisa (Mrs. Squires), of

Blanshard; Arthur, of Blanshard; Mary Rebecca (Mrs. Wilson), of Biddulph;

Alice (Mrs. David Parkinson), of Usborne; Lucy, at home, and a little

boy who died in infancy. After his second marriage Mr. Gunning at once

returned to Canada and went to reside at Chippawa. Here he again found

employment as a ship-builder on board a new steamer that was then being

built there. On the completion of this vessel she was taken to Buffalo

for the n purpose of being finally finished and painted, preparatory to

beginning her regular trips on the lakes. On her trip from the dock in

the Chippawa River an event transpired which nearly culminated in the

most terrible disaster that had ever occurred in Canada. On a bright and

beautiful morning, early in the spring of 1847, the ship was cut loose

from her moorings and pushed into the stream, steering for the Niagara

River. This vessel was considered a wonderful triumph of the

shipbuilder’s art, and a great excursion was arranged to go on board and

accompany her to Buffalo. The decks were crowded with people, and along

the shore were gathered large crowds of spectators to see the great

leviathan move out of the still waters of the Chippawa and into the

broad Niagara. At length the hawsers were cast off, amid the cheers of

the people on the shore as well as of the crowd on deck, and onward and

outward she moved into the stream. She soon reached the current leading

to the Falls, and her head was being turned up the river, when her

engines stopped, and in spite of the best engineering skill on board,

refused to move. The current at the mouth of the Chippawa is strong, and

swung her bows in a few minutes down the river, and with increasing

speed was carrying her downward to the terrible abyss of the Falls. In a

moment all was changed. The happy crowd on board, who a few minutes

before were sharing with each other their ecstasies of delight, broke

forth in one heart-rending shriek that struck the strongest hearts numb

with terror,—one wild, agonizing cry for help, where no help could be

given, that soon died away into the dull delirium of despair. The crowds

on the shore were helpless to give aid to the drifting ship as she moved

on with increasing speed to the fatal plunge over the Falls. At last,

when all hope seemed gone from the doomed excursionists, the engines

began to move. Every man took his post as with bated breath he watched

the laboring machinery battling with the current, till, to the heartfelt

relief of all, she began to make headway in the stream and soon was out

of danger.

COMING TO BLANSHARD

After making several

trips in this ship from Buffalo to Detroit, Mr. Gunning, in the fall of

1847, decided to commence farming for himself in the new country then

opened up in the west. Mr. Street, a gentleman then residing in Niagara,

had a large quantity of land in the township of Delaware, of which he

wished to dispose. Mr. Gunning removed his wife to the city of London,

from which place he walked to Delaware and inspected the lands of Mr.

Street, none of which he was able to purchase, not having the necessary

funds. On his return he casually met on the street a farmer who had a

short time previously settled in Blanshard. This gentleman was so

enthusiastic over the splendid soil and other natural advantages of that

new section that Mr. Gunning decided at once to go and spy out the land

for himself. He accordingly left London on foot and walked out to the

township, and after satisfying himself as to the quality of the land,

selected lot 3 in the 12th concession, where he has lived continuously

ever since.

Having selected his

farm, he had at once to get the necessary papers from an official of the

Canada Company. To effect this he had to go to Goderich, this being the

nearest office at which he could transact his business. To Goderich he

went, and on foot, a distance of nearly fifty miles. But those were the

days when men faced difficulties with strong hearts and a determination

to overcome them. All that could be accomplished by physical labor they

proceeded to acomplish. Distance, hardship, trackless forests, had no

deterring effect on the pioneer. The law of the survival of the fittest

was amply proved in the new settlement. If the settler was not strong

and robust he soon went to the wall. There was no opening for any line

of business in a new country where all were poor. If a man could not

chop, make log heaps, split rails, and live on pork and potatoes, he was

of no use in the woods, and the sooner he removed the better. Mr.

Gunning was equal to all these, and started for Goderich with a chunk of

pork and some bread in his wallet, as happy as a lord. The first day he

reached Clinton, and obtained quarters for the night at Rattenbury’s

Hotel. On the second day he reached Goderich, transacted his business

and returned as far as Brucefield, where he again stayed for the night.

The third day he reached home, or the place he intended to make his home

in Blanshard. There was not a stick chopped on his new place. He had few

near neighbors, but he entered with a will on the labor of building a

shanty where he could bring his wife in the winter. The shanty was soon

built, covered with troughs in the true style of that architecture, the

walls chinked, a good coat of mud put over all, a huge fire-place made

in one end, and, thus completed, Avas ready to receive his young wife.

The change from the beautiful fields of Somerset to a shanty in

Blanshard was great indeed.

But hope still led them

on. It was easy to endure when endurance would be so amply rewarded. In

the winter of 1847 and 1848 he chopped a fallow on the new farm, and was

able in the spring to clear two acres, which he sowed in spring wheat

and planted in potatoes. His small store of cash was by this time

completely exhausted, and to obtain a little money it was necessary that

he should go to some of the older settlements for that important

purpose. He left in the summer of 1848, and naturally turned toward

Niagara, where he had formerly been employed. He walked as far as

Flamboro’, and got employment in a saw-mill for a couple of months. It

was then nearing the time for him to return and harvest his little crop

of wheat. Unfortunately, however, the proprietor of the mill was unable

to give him any money, and all he got at that time for his work was an

attack of the ague. Under those circumstances his employer, by making

extra exertions, was able to secure him a couple of dollars, with which

he started on his return journey. The attack of ague was so severe that

it took him five days to make the trip home, where on his arrival he was

some time before he could do any labor of any kind. With the help of his

brother James, who was now in Canada, he succeeded in securing the

little crop on which they were to subsist till another harvest. In the

February following he again returned to Flamboro’ for the purpose of

earning a little money as well as to try and recover what he had already

earned. On this occasion he worked one month and was able at the same

time to obtain something from his former employer. His remuneration was

not in cash, but consisted of a pair of boots, a cow, some clover seed,

and a barrel of salt.

The barrel of salt he

sold to get some funds to pay his expenses home. His boots he wore on

his feet, the cow he drove, and the clover seed he carried on his back.

After an eventful journey of several days he at last reached Blanshard,

completely exhausted but still carrying his clover and driving his cow.

During the next summer he again set out for Flamboro’ to earn money, and

on this occasion he was more successful, having improved his financial

condition to the extent of fifteen dollars. This was his most successful

and his last trip to the old settlements to obtain ready cash. In the

meantime his brother James had cleared and prepared for crop several

acres, as well as having gotten the logs ready for a new barn. They had

also bought a yoke of oxen, two young cattle, and a pig, and, all things

considered, had fairly launched out on a career of prosperity.

The military spirit

fifty years ago in Canada was exceedingly strong, and was cultivated by

the settlers as well as the government to a high degree. Many of the

settlers in the eastern part of the province remembered and had taken

part in the war of 1812. A number of the settlers in Blanshard had taken

part in the outbreak of 1837. The feeling of loyalty to-the land of

their birth, and of determination to stand by the old flag, was deep

seated in the bosoms of the Canadians. Many of them had suffered on

those two occasions for their devotion to British institutions and

British freedom. Under her protecting hand they had been born, under her

protecting hand they lived, and under her protecting hand they

determined that Canada should remain. As loyal Canadians then, as loyal

Canadians now, (and as loyal Canadians we hope and trust we will always

remain) they were proud of the Empire to which they belonged, and were

prepared to defend her to the death. We believe that feeling exists

to-day to a greater extent than ever before. We are proud to pay homage

to our beloved Queen. The glory of the Empire reflects itself upon us.

Her achievements on land and sea are dear to Canadians. In the quiet

churchyards of those islands repose the dust of our fathers. Britain is

the mother of our civilization, the defender of our rights, the guardian

of our liberties ; and the Canadian that would barter his privileges as

a free-born citizen of the grand old empire for a position with a

bombastic and ignorant democracy is unworthy of the great nation from

which he sprang.

For the purpose of

keeping up the military spirit among the people, all able-bodied men

between the ages of twenty-one and sixty were enrolled in the militia

and had to meet at some particular place once a year for training and

instruction. In a former sketch (of Mr. Cathcart) we attempted to

describe one of those gatherings on the flats in St. Marys. The meeting

we are now to describe was one of the same description, but in a much

more grand and extended form. The gathering in St. Marys embraced the

military men of Blanshard and St. Marys only. In this case seven

townships were concerned, and the camping ground was at Carronbrook, or

what is now known as the village of Dublin. The Blanshard and St. Marys

contingents were to rendezvous at Skinner’s Corners, and march on foot

from that point to Carronbrook and join the men from the north and west,

The troops were commanded by Major Sparling and Mr. Cathcart as captain.

On the day appointed, Mr. Gunning repaired to the mustering place with

the usual supply of pork and bread stowed on his person. Of the

gentlemen who composed the commissariat department no record can be

obtained. The cuisine was, however, of the simplest description,

although somewhat of an indigestible character. For breakfast the men

had bread, pork and whiskey; dinner, whiskey, bread and pork; supper,

bread, whiskey and pork. This bill of fare wras simple indeed, but it

was marvellous the effect it had on the men. Each repast was followed by

an exhilaration and exuberance of spirits among the troops which an

ordinary spectator would have considered incompatible with a ration of

bread and pork. As to the quantity of each served, we cannot after an

interval of fifty years exactly say. It is reasonable to suppose,

considering the manners and the state of society at the time, that

whatever the allowance may have been of the solids, the fluids were

unstinted and plentiful. The order was at length given by the Major,

“Forward, march!” and away trudged the old pioneer settlers through the

dust and heat on their long, weary march of twenty-five miles, to learn

the way in which fields were won. The summer sun swung low over the dark

forest away to the west, and flung deep, dark shadows over the leafy

woods as the men from the south, tired and dust-covered, drew near the

camp at Dublin. Early in the afternoon the various corps from Hibbert,

Logan and other townships had arrived and were bivouacked on the west

side of the village, and were lounging in groups at their ease,

discussing the events of the day. As we stated elsewhere in these

sketches, the township of Blanshard was settled largely with emigrants

from the North of Ireland. Many of these old settlers were members of

the Orange order before they came to this country, and those who were

not actual members were strongly in sympathy with the Orange body. On

the other hand, nearly the whole of the north-western portion of Hibbert,

a large portion of Logan, as well as the village of Dublin itself, were

settled with members of the Roman Catholic Church. Unfortunately for

both parties, the feuds that existed between the admirers of the Prince

of Orange and the sons of those men who had followed the fortunes of

Brian Boru, had been brought with them to Canada and still burned

fiercely in their bosoms. The Blanshard men, as a testament to their

loyalty, had brought a flag on which was imprinted the hero of “pious,

glorious and immortal memory.” As might be expected, this was most

distasteful to the sons of the Church, and aroused their deepest

indignation. The old settlers, as a class, were not slow in showing

their approval or disapproval of anything, in a manner most emphatic,

and in this case the resentment of the Hibbert pioneers soon manifested

itself in unmistakable demonstrations. On a bridge over the creek that

flows past the village on the Huron road, along which came the Blanshard

corps, a number of the Hibbert men soon stationed themselves, to dispute

the passage into the camp of the troops from the south. This looked

ominous to the southern contingent, but on they came like dauntless

heroes to the fray. They had no sooner gained the bridge than they were

met with a volley of stones, and the application of their stout cudgels

by the Hibbert men soon brought to a stand the champions who were

guarding the flag. Still they pressed on ; as one warrior was placed

hors de combat another stepped into his place. A small party of the

invaders moved up the stream for the purpose of crossing to attack the

enemy in the rear, but as it was somewhat swollen they had to relinquish

the attempt. Meanwhile another party had descended the creek for the

purpose of crossing to operate on the right flank of the enemy, but they

also failed in the attempt. Being thus unable to cross either on the

right or the left, the whole force concentrated on the bridge, where the

fight still raged with unabated fury. The noise, the shouting, the

imprecations of the contending factions were terrific. Men were knocked

down, trodden upon and cudgelled, until both parties retired completely

exhausted. The Hibbert men still held the bridge. Mr. Gunning, who was

not at all an excitable person, stood at some distance with a number of

others and surveyed the field. A short time ago the writer had occasion

to visit Dublin, and was introduced to an old gentleman who was present

and took part in the fight on the bridge. His account of the affair was

substantially the same as that which we have given—with this important

difference, that while Mr. Gunning claimed a victory for his party, my

Dublin friend says that his party “knocked the devil out of the

Blanshard fellows.”

During the recital of

the events of that engagement my aged friend became quite excited, as

one scene after another passed in review before his mind’s eye. We

mildly ventured a remark that it was most unfortunate for the Blanshard

heroes, that having the devil knocked out of them in such a summary way,

there were no pigs in that new country in which he could find a resting

place as of old, and he was forced to return to his old quarters, where

he has ever since held his ground in spite of the influence and efforts

of clergy. The belligerents on both sides of the stream, completely worn

out by their long march and their efforts at the bridge, had retired to

the woods. Here and there among the brush heaps were little knots of

men, calmly sleeping, in happy oblivion of all that had passed, while in

other parts of the forest rang out on the ear of night the laugh, the

jest, and the merry song of more restless spirits. The officers,

however, were afraid that a new day would bring renewed energy and new

cause of quarrel amongst the troops. They therefore spent a good portion

of the night counselling with the leaders on both sides, and with such

success that the real business of the camp proceeded without any further

interruption. The sun next morning rose bright and clear, sending golden

rays over the dark woods, and bathing the camp in a stream of glorious

light. The reveille was sounded on a dinner-horn which was provided for

the occasion. The men performed their ablutions in the little stream

that ran through the camp, and having partaken of the morning ration of

bread, pork and whiskey, fell into the ranks to perform the duties for

which they had met. Not being a military man, I am unable to describe

the various evolutions in which the troops were engaged during the day;

but I have no doubt they were of a character such as would fit the

participants for active service in defence of the country they all loved

so well. On the third day the camp broke up, and all returned tired and

weary to their humble homes, scattered here and there in the wild woods

of the Huron Tract. So ended the great farce of battalion drill among

the sedentary force of Canada of fifty years ago.

ADVENTURE WITH A BEAR

We must now revert to

another circumstance in which the Gunning brothers were participants,

and only for the merest chance I should have had one sketch less of the

old pioneers to place before my readers. This was an encounter with a

bear.

The southwest corner of

Blanshard, unlike the other parts of the township, was exceedingly

swampy and wet. For over two miles along the Usborne side of the west

boundary, and parallel to it, ran a great marsh, which all along

extended here and there across the townline into Blanshard. This corner

was long known as the “jumping-off place” and was as uninviting in its

appearance as a new country could possiby be. From the eighth concession

along to where Whalen post-office now is, the road was nearly all

corduroy. Beavers had at one time been plentiful in this section, and

numerous dams still remain to attest the untiring energy of these

laborers. Here and there they had made clearances, amounting in some

cases to several acres in extent. After the removal of the large timber

by those industrious little animals, an undergrowth of the white thorn

and other scrubby timber had grown up to take its place. This afforded

the best of shelter for wild animals, particularly bears.

An innocent pig, which

was returning to his home after the day’s foraging in the woods, offered

a tempting morsel for bruin’s empty stomach. He at once seized the poor

pig, which in turn gave the alarm by his unearthly squealing. This

brought the settler to his assistance, but he did not succeed in saving

all his property, as bruin decamped with both the ears of the poor

porker. The settler, as soon as he could, informed the Gunnings, his

nearest neighbors, who with a young lad, a son of Mr. Morley, started in

pursuit of the bear. William armed himself with a gun, James took his

axe, and with two dogs the hunt began. After beating for some time the

dogs got the scent and followed the animal for some distance into what

was then called the marsh—a piece of land which had been cleared by the

beavers, but which was thickly grown with undergrowth. In this spot the

dogs came up with the bear, which at once began to defend himself.

James, who was younger than William, had out-run him in the pursuit, and

arrived first on the scene. The dogs, encouraged by the presence of Mr.

Gunning, closed in on the ferocious animal so closely that he struck at

one of them with his paw and killed him on the spot. The other dog kept

at safer distance, when the bear began to move toward James. William had

now nearly reached the scene of action, and the bear coming toward

James, he shouted to his brother to fire. William took aim and fired,

the ball striking the animal in the shoulder, severely wounding, but not

killing him. The brute then, more fierce than ever, sprang toward James,

who struck at him with his axe. The wound in the shoulder by the ball

that William had fired gave him a sort of rolling, uncertain motion, and

as he sprang on James he miscalculated his distance, but caught him by

the knee-cap, pulling him to the ground. Fortunately for him the bear

had no sooner clinched his knee than he let go his hold. In a moment he

was on his feet, but not any too soon, as the bear sprang once more at

his antagonist, who still held on to the axe. The trusty steel fell once

more, and this time with unerring aim, when its sharp edge crashed deep

into the skull of the infuriated beast. All this occurred in less time

than I have taken to write it, and William had by this time reached the

place of struggle, and, clubbing his gun, they soon dispatched their

victim. It was many months before James could use his limb, and the

marks of this encounter he will carry to the grave.

The lynx or wild-cat

was at that time quite numerous in this corner of the township. On one

occasion the writer was returning from a neighbor’s home at a somewhat

late hour, and passing through a piece of swamp, was startled by a most

unearthly sound in the wTood near the roadside, and which he knew was

the yell of a lynx. Being somewhat of a retiring and inoffensive

disposition, he had no desire to win distinction by the destruction of a

wild animal, as would no doubt have been the result of an encounter. The

evening was beautiful and mild, but it occurred to him at once that the

night was intensely cold and an increase of speed might add to his

comfort. He accordingly tried to increase the distance as quickly as

possible between himself and the spot from which the sound had emanated.

Another blood-curdling yell produced an acceleration of motion, and he

obtained a mark in his record on that occasion he has never been able to

break since, and which, to those who know his deliberate and quiet

dignity of movement of late years, would appear perfectly marvellous.

WILLIAM’S BLANSHARD

FARMS

But the whirligig of

time brings round its changes. Years had come and gone and brought many

alterations in the conditions of the Gunning brothers. The oxen and the

sled on which William made many trips to London with his produce, had

given place to horses and wagon. The roads had been improved, and his

surroundings furnished the clearest evidence of prosperity. He had no

longer to walk to St. Marys as the nearest post office, nor had he to

walk to London to consult his family doctor. His industry and thrift had

been amply rewarded by a goodly portion of the world’s goods. In the

sixties he not only was the owner of lot 3, on the 12th concession, but

he also owned lot 21, on the W. B., and lot part 5 and the whole of lot

6 in the 11th—between 300 and 400 acres of splendid land.

In 1869 he built the

splendid residence on the homestead in which he at present resides, and

was in every way a most prosperous man.

Before dismissing this

part of our sketch we must not omit an event which occurred on January

27th, 1896. That was the golden wedding of William and Mrs. Gunning.

This was a great occasion, and over one hundred guests sat down to a

splendid repast served by kind hands in a splendid style. Numerous and

costly presents were given to the old couple by their friends. Amongst

those present were ten of their own children and thirty-six

grandchildren (at time of writing they number forty).

James, who had resided

with him since he came to Canada, decided to begin the battle of life

for himself. Up to this time the lives of the two brothers had been

inseparable. In 1855 James married Miss Savior, a sister of his

brother’s wife, and having built a shanty on lot 21, W. B. concession,

commenced to clear on his new farm. This lot was not by any means a good

one, at that time being wet and swampy. But he soon made a change. By

unceasing toil, and in spite of many adverse circumstances, he

transformed it into one of the best farms in that section. He possessed

in an eminent degree those qualities which lead to success in a new

country. He was a master with the axe, and as eorner-man on a building

could not be excelled. As a natural consequence there were few log

buildings in that section on whose corners could not be seen his

handiwork. “Saddle and natch,” “flat corner or dovetail” to him were

equally familiar, and he rarely missed taking a log from the “muleys,”

no matter how high the structure might be. As time passed away, his

energy and thrift led to an increase in his world’s possessions, and he

is now the owner of 300 acres. Such success speaks volumes, not only as

to the character of those clever, energetic men who have made this

country, but it also proves the splendid opportunities and the results

this country offers as a reward for honest effort and perseverance. In

the year 1891 he had the misfortune to lose the mother of his children,

who had struggled with him in the woods so faithfully and well. The

issue of his married life are, Eleanor (Mrs. Leaf), of Manitoba; Robert,

of Biddulph; Alfred, of Blanshard; Agnes (Mrs. Foster), of Blanshard;

Sarah (Mrs. Ashton), of London; Fred, of Blanshard; Elizabeth (Mrs.

Johnson), of Blanshard; Thomas, of Blanshard; Annie, at home; George, in

Manitoba; and Francis Albert, of Blanshard.

A few years ago Mr.

Gunning again married, and was fortunate in taking to his home a most

estimable helpmate, in the person of Miss Janet Taylor. This lady now

presides over his household with the greatest kindness and

consideration, and is equally esteemed by her husband and the whole

family.

SOCIALLY AND MORALLY

It would be hardly

possibly to find two men more alike, not only as to their personal

appearance, but as to their manner of thought and moral qualities, than

the two gentlemen who form the subject of this imperfect sketch. Both

are under the average size and sparely made, and yet possessed of powers

of the greatest endurance and energy; their muscles seemed like wires of

steel. They understood their business well, and were exceedingly tidy on

their farms, having “a place for everything, and everything in its

place.” Equally industrious in their habits, always ready to help each

other, the lives of both men have been a great success. Neither of the

brothers had any desire for distinction in public life, and as a matter

of course neither has ever sought or obtained public office.

Neither of them is fond

of show, but both take great pride in having everything in the best

possible condition on their farms. They are strictly sober in their

habits, honorable and upright in their dealing, and discharge to the

fullest extent the responsibility of citizenship. They are strongly

Conservative in politics, believing the principles advocated by that

party to be for the best interests of their adopted country. As

politicians they are not blatant, being willing to accord to every man

the right that they claim for themselves, that he should think and act

according to the light that is in him. In religion they belonged to the

Church of England, but of late years have attended the Methodist Church,

it being more convenient to their families.

In their homes, like

all other old settlers, they are kind and hospitable, and ready to help

any good cause to the best of their ability. We have never seen two

families in which so strong a bond of sympathy exists as exists in the

families of the Gunnings. Their reunions are frequent and enjoyable. The

good nature and the pleasure they seem to take in each other’s company

is to an outsider delightful indeed. The kindness and consideration of

the young people in their home life, the simplicity of their amusements,

the confidence in and love for each other, the good nature that seems to

pervade all and crown all, impresses one with the feeling that there is

really a great amount of good in the world after all. When we think of

the cold-hearted selfishness and bitter strife, and the harsh treatment

meted out to near relations in many homes, we turn with delight to such

spectacles of endearing love for their aged parents and each other as

Ave see in the two families of Gunnings. But we must draw this sketch to

a close with the hope that the Gunning brothers may long be spared to

enjoy the fruits of their toils, and when the final hour comes, as come

it must to all, that they also will be found watching to welcome the

grim messenger that shall call them to a higher life. |