THE French profess the

right by Treaty, of catching and drying fish from Cape Ray on the west

through the Straits of Belle Isle as far as Cape St. John northward,

though they are not allowed to make any fortifications, or any permanent

erections, nor are they permitted to remain longer than the time

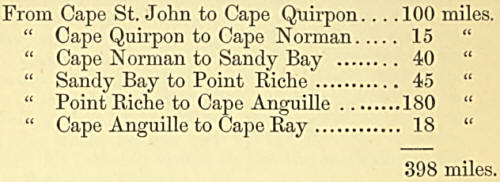

necessaiy to cure their fish. This line of coast is as follows :—

The whole line of shore

in exclusive use of Great Britain, is 535 geographical miles. The number

of inhabit tants on the west coast is about 2,300,principally Acadians,

descendants of the French, from Nova Scotia and the Island of Cape

Breton, interspersed with English, Irish, Scotch and Canadians. The

coast is fast settling. Hitherto the Government of Newfoundland has

exercised no control over the inhabitants of this part of the country,

and of course they have not been represented in the Legislature. In

1849, the Government appointed a gentleman in the two-fold capacity of

Stipendiary Magistrate and Collector of Customs to reside at St.

George’s Bay, but after a short residence there he removed.

The principal places on

the West-Coast are Cod-Bay, St. Caspars Bay, River Humber, Bonne Bay,

and Port-au-Port, St. George’s Bay and the Bay of Islands, are

geologically interesting. All who have ever visited this part of the

country, describe its scenery as exceedingly interesting and beautiful.

It has all the elements of future greatness. Here is a coal field thirty

miles long and ten broad, situated only eight miles from the sea, and

twenty miles from St. George’s Harbour, supposed to be a continuation of

the coal mines of Cape Breton. There is also marble of almost every

variety and colour, some masses of which are five hundred feet in

height. There are also soft sandstones, flagstones, gypsum, &c. Had this

part of the country been settled first, instead of the eastern portion,

it would now have a population of some hundreds of thousands. In this

portion of the country there are all the elements to set in motion

agriculture, manufactories, steam, vessels, railroads, and architecture.

The amount of salt

annually imported into Newfoundland is about 900,000 bushels, which is

mostly consumed by the fisheries. It was never manufactured in

Newfoundland until 1850, when Mr. John H. Warren commenced to

manufacture it on a small scale, at St. John’s, from sea water, but

discontinued it. There are several salt springs at St. George’s Bay, the

brine of which, if manufactured, would probably afford sufficient salt

for the convenience of the country. The geological formations where

these springs exist are identical with those of England, Spain, and the

United States.

The quantity of coals

imported into Newfoundland in 1875 was 27,034 tons, principally from

Cape Breton. The produce of the Pictou coal mines in 1855 was 820 tons,

valued at £47,699 or $190,796. And of the Sydney mines, 26,877 chaldrons,

valued at £20,274 or $82,000. From Nova Scotia, 50,785 chaldrons were

exported to the United States from Cape Breton, 10,125 were sent to Nova

Scotia, 6,617 to other British colonies, and 10,942 to the United

States. The importance of the coal fields of St. George’s Bay is very

apparent, when we consider its proximity to Canada East, where no coal

is found, and wood fuel is rapidly disappearing. Firewood is also

rapidly becoming very scarce along the sea board of the eastern shores

of Newfoundland, where there is a population of 160,000. The following

are the observations of 0. J. Brydges, Esq., Managing Director of the

Grand Trunk Railway of Canada, in li566 :—

“Whilst I was in Nova

Scotia I visited Pictou and the coal districts in its vicinity. The

present railway system of Nova Scotia consists of the railway system

from Halifax to Truro, with a branch to Windsor, at the head of Minas

Bay. The Nova Scotia Government are now constructing, as a Government

work, an extension of the railway from Truro to Pictou, which will be

completed in about a year from this time. This railway runs through the.

coal district. There are two principal coal mining companies now at

work—one, the General Mining Association, has been in operation for a

considerable, time, and has at present three mines in actual operation,

and one more which they are opening out. The shafts of these mines vary

from 200 to 600 feet in depth. The seam of coal which is being worked is

40 feet in thickness, of which about 36 feet is solid coal. In these

three mines there are at present employed between 800 and 1000 men and

boys. The average pay of the colliers during the last year having been

about 9s. 4½d. currency a day; ordinary labourers getting from 4s. to a

dollar. The mines are being worked very extensively with steam-engines

and all proper appliances. The General Mining Association have a rail

way about seven miles in length, which has been in operation for upwards

of twenty years. The gauge of this railway is four feet eight and a half

inches, and they have upon it six engines and five hundred and seventy

trucks. These trucks are loaded with the coal at the mouth of the pits,

and are taken to a point on the river where ships of the largest size

can come alongside the wharf. The quantity of coal which has been

shipped by the Mining Association for some years past has amounted to

about 200,000 tons annually. The price of the steam coal at the point of

shipment is about $2.50 per ton, and of small coal about $1.50 per ton.

“Freight from Pictou to

Boston would range from $2.50 to $3 a ton, the same rates, or

thereabouts, being charged to Montreal. This company owns four square

miles of coal land, and they have also, in the vicinity, land containing

very large quantities of iron ore, as well as lime.

“The other mining

company, which has lately be started, is called the Acadian Mining

Company. They have one seam six feet thick now opened, out of which they

are getting coal, and they have just opened another seam which they will

begin immediately to work, and which has a thickness of 20 feet. They

own a very large property in the neighbourhood of New Glasgow. They are

about to make three miles of railway, to connect their shafts with the

railway now being constructed from Truro to Pictou. The quantity of coal

appears to be inexhaustible, and there seems to be no reason why this

coal, which is of excellent quality for steam purposes, should not be

delivered in Montreal for five dollars a ton. I was so satisfied with

the excellent quality of this coal, from the reports I heard of it, that

I ordered several cargoes to be sent to Montreal for the use of the

Grand Trunk Company, so as to have it thoroughly tested for our

purposes. There can be no doubt that the coal which exists in Nova

Scotia, in the neighbourhood of Pictou, and also at Cape Breton, where

large mining operations are going on, will prove, when proper means of

communication are supplied, to be of great importance in the future

history of the Confederacy.”

Professor Sedgwick, of

the University of Cambridge, recommended J. B. Jukes, a graduate of that

university, a member of the Geological Society of England, and

afterwards a professor of Geology in Trinity College, Dublin, and author

of several works, as a competent person to make a geological survey of

Newfoundland. Mr. Jukes was accordingly employed by the Local Government

for two years, 1838 and 1839. He was but poorly provided however for

making the survey, he had no geological probe, and few instruments for

boring, &c. Mr. Jukes merely made a partial survey of the sea coast, aud

went nowhere into the interior, except a line from Bay of Exploits to

St. George’s Bay. His Geological Report, however, laid before the

Legislature, is exceedingly interesting, and gives more information

respecting the geological structure of the Island than was ever known

before. Respecting the coal formation of St. George’s Bay, Mr. Jukes

says:

“This interesting and

important group of rocks resembles in its higher portions the coal

formation of Europe, and consists of alternations of shale and clunch, w

ith various beds of gritstone and here and there a bed of coal.

Interstratified with those rocks, however, there occur in Newfoundland

beds of red marl; and as we descend to the lower parts of the formation,

there come in alternations of red and variegated marls with gypsum, dark

blue clays with selenite, dark brown conglomerate beds, and soft red and

white sandstones. This inferior portion of the Newfoundland coal

formation so greatly resembles the new red standstone of England (which

in that country lies over the coal formation), that it was not till I

got the clearest evidence of the contrary that I could divest myself of

the prepossession of its being superior to the coal in this country

also. That nothing might be wanting to complete the resemblance, a brine

spring is known to rise in one spot on the south side of St. George’s

Bay, through the beds of red marl and sandstone. It is certain- however,

that in Newfoundland the beds containing are above these red marls and

sandstones, with gypsum and salt springs, the whole composing but one

formation, which it is impossible to subdivide by any but the most

arbitrary line of separation. The total thickness of this formation must

be very considerable. I by no means have any reason to suppose that I

have as yet seen its highest beds, while the thickness of those which I

have seen must amount altogether to at least one or two thousand feet.

“The Humber

Limestone.—This group of rocks lies below the Port au Port shales and

gritstones, and in the Bay of Islands it is the one next inferior; as

however their junction was not exposed, I cannot say whether the one

graduates into the other, or whether other beds may not be interposed

between the two in other localities. The highest part of the Humber

Limestone which was visible, was a thin bedded mass, about 30 feet

thick, of a hard, slaty limestone of a dark grey colour, with brown

concretions that, on a surface which had been sometime exposed, stood

out in relief. Below this are some thin beds of hard subscrystalline

limestone, the colours of which are white or flesh-coloured with white

veins. These would take a good polish, and would make very ornamental

marbles, and from the thinness of the beds are especially adapted for

marble slabs. This series of beds has a thickness of about 200 feet.

Below these are a few feet of similar beds of black marble, which rest

on some grey compact limestone, with bands or thin beds and irregular

nodules of white chert; and these latter beds pass down in a large mass

of similar limestone, without chert, and in very thick beds. This mass

of rock forms hills four or five hundred feet high, in nearly horizontal

beds. Its upper part continues to be regularly bedded, but in its lower

portion all distinction into beds is lost, and the limestone becomes

perfectly white and saccharine. This great mass of white marble is

frequently crossed by grey veins, so that I cannot say that I saw any

block pure enough for the statuary. There is little doubt, however, that

in so large a quantity, some portions might be discovered fit for

statuary marble, and for all other purposes to which marble is applied,

the store is inexhaustible.

"The hills about the

head of St. George’s Bay, though rarely exceeding one thousand feet in

height, are of a mountainous character, rugged and precipitous; and this

continues to be the nature of rather a wide band of country, that runs

from the east of St. George’s Bay across the Humber River, at the head

of the Bay of Islands, and thence for a considerable distance still

farther north. About St. George’s Bay this ridge of hills forms the

water-shed of the country ; the brooks on one side running down into the

Bay—those on the other emptying themselves into the Grand Pond, a large

lake in the interior. This lake commences at about fifteen miles in a

straight line N.E. from the extreme point of St. George’s Bay. In the

first seven miles the lake spreads out to a width of about two miles,

and runs about E. S. E. ; at this point, however, it bends round,

divides into two branches, each from half a mile to a mile wide, which

enclose an island about twenty-one miles long and five across in the

broadest part. In this part of its course the direction of the lake is

E. N. E. The remainder of the lake, which is about twenty-live miles

long and four or five across, gradually tends round to the N. E. and N.

E. by N. The whole length of the lake is about fifty-four miles. At its

S. W. extremity it is enclosed by lofty hills with precipitous banks,

and is of great depth, no bottom having been found with three fishing

lines, or about ninety fathoms. Its depth is further proved by the fact,

of the truth of which my Indian guide assured me, that its S.W. half is

never frozen over in the hardest winters. Towards its N. E. end it

gradually becomes shallow, and the hills slope down into a flat country

which extends, as far as the eye can reach, towards the N. and N. E. The

lake receives on all sides many brooks, and at its N. E. extremity a

very considerable river, fifty yards wide and several feet deep, comes

in, which is called the Main Brook. Three miles W. of the mouth of this

river, an equally considerable one runs out of the pond; this latter is

full of rapids for five or six miles, when it is joined by another river

of about the same size, which flows from the North-West. These united

rivers run towards the S W. and in about six miles enter Deer Pond, a

lake about 15 miles long and 3 or 4 across, running in a direction about

N. E. and S. W. The S. W. end of this lake is again encircled by the

hills, through which the united waters force their way by a narrow and

precipitous valley, forming the River Humber, and running out into the

Bay of Islands. The part of the river between Deer Pond and the sea is

about twelve miles long, from about 50 to 100 yards across, and several

feet deep ; its navigation is, however, impeded by two rapids, one about

three miles from its mouth and three quarters of a mile long, and

another, shorter but steeper and more dangerous, about half a mile below

Deer Pond. The river which, above Deer Pond, comes in from the north and

joins that running out of the Grand Pond, is likewise encumbered with

rapids, our progress up each branch being stopped half a mile from their

junction by rapids utterly impracticable with our boat. I afterwards

interrogated the Indians respecting the course of the river in those

parts into which I was not able to penetrate myself, and they informed

that the north branch, which I shall call the Humber, rises in the

country near Cow Head, passes down to the east through several lakes,

two of which are 8 or 10 miles long, and gradually bends round to the S.

or S. W., to the spot I have before described. The main brook which runs

into the N. E. end of the Grand Pond, is navigable for a canoe for a

distance of some miles above the place where I turned back. It is there

found to run out of a lake 8 miles long; on the other side of the lake

the river is again met with, and passing up it three more lakes are

crossed, each above six miles long. The extremity of the last of these

is about 18 miles from Hall’s Bay, a branch of the Bay of Notre Dame ;

and crossing half a mile of land another brook is met with, down which a

canoe can proceed to the waters of that Bay. It thus appears that the

country drained by the Humber is upwards of one hundred miles from N. to

S., and fifty or sixty from E. to W., by far the most extensive system

of drainage in the Island ; it approaches the sea on three points,

namely, Cow Head, Hall’s Bay, and St. George’s Bay, and the united

waters force their way out at a point nearly equidistant from each,

having either formed for themselves or taken advantage of the narrow

pass between Deer Pond and the South branch of the Bay of Islands,

called Humber Sound. The Indians likewise informed me that if they

proceeded from the east side of the Grand Pond, opposite the east end of

the Island, a day’s journey to the east brought them to the South end of

Red Indian Pond, a lake between forty and fifty miles in length, and

from that point another day’s march to the South-east brought them to

the middle of another large pond of about the same size. Each of these

ponds empties itself by a brook into the Bay of Exploits. They each run

about in a parallel direction with the Grand Pone, or about N. E. and S.

W., and the S. W. end of the third large pond is within a long day’s

walk of White Bear Bay. It thus appears that there are two easy methods

of crossing the the country from north to south with a canoe. The first

by proceeding from St. George’s Bay, through the Grand Pond to Hall’s

Bay ; the second from White Bear Bay, through the third pond to the Bay

of Exploits.

“In the cliffs near

Codroy Island is much red and green marl, with bands of white flagstone.

The white flagstone and the greenish marl contain many veins of white

fibrous gypsum, and interstratified with these and the red marls are

some thick beds of white and grey gypsum, of a singular character. These

P gypsum beds are not hard, compact sulphate of lime, but are composed

of white flakes of that substance, regularly laminated, and interspersed

with small flakes and specks, or sometimes thin partings of a black

substance, apparently bituminous shale. The whole mass is soft and

powdery, thick bedded, and in considerable abundance, and it might be

carried away in boats with great facility.

“I was informed by some

Indians of Great Codroy River that they had seen a bed of coal two feet

thick, and of a considerable extent, some distance up the country. Their

account of the distance, however, varied from ten to thirty miles ; and

I could not induce any of them to guide me to the spot. I proceeded up

the river abont twelve miles from the sea, and some distance beyond the

part navigable for a boat, without seeing anything but beds of brown

sandstone and conglomerate, interstratified with red marls and

sandstones, gradually becoming more horizontal and dipping towards the

S.E. I believe, however, that a bed of coal had been seen by an Indian

on the bank of a brook running into Codroy River, about thirty miles

from its mouth, but that the person who saw it was not in the

neighbourhood at the time of my visit.

About the middle of the

south side of St. George’s Bay, in the vicinity of Orabb’s River, the

lower part of the coal formation, consisting of alternations of red marl

and sandstone, strikes along the coast, the beds dipping to the N\\V. at

an angle sometimes of 45 degrees. About three miles from tho coast,

however, ananticlinal line occurs, preserving the same strike as the

beds, or about N.E. and S.W., and causing those to the south of it to

dip to the S.E. Thus the rocks which form the country along the coast,

to the width of three miles, with a New. dip, again occur to the same or

a greater width, according to the angle of their inclination, with a dip

to the S.E. before we can expect to find any higher beds than those in

the sea cliffs ; so that at least six miles of country formed of the

lower beds must be crossed directly from the coast, before we arrive at

the higher beds in which the coal is situated.

“In ascending the brook

next above Crabb’s River I found on tho sea coast beds of soft red

sandstone and red marl, and, half a mile up the brook, red and whitish

sandstones, interstratified with beds of marl, chiefly red, but also

occasionally whitish, green, or blue; beyond that were beds of marl,

containing massive grey gypsum, similar to that at Codroy, and a bed of

blue clay, containing crystals of selenite. Similar rocks, with now and

then a bed of brown or yellow sandstone, occurred throughout the first

two or three miles, all dipping N.W. at various angles of inclination.

Beyond this point the dip was invariably S. or S.E., and for two or

three miles further the character of the rocks was precisely similar to

those I had already passed. As, however, the banks of the brook were

occasionally low, the section observed was of course not perfectly

continuous, and beds which were hidden on one side of the anticlinal

line, formed cliffs, and were thus exhibited on the other side. Thus, as

I continued to ascend the brook, I came on a cliff of red marl, fifty

feet thick, with some thin grey soft micaceous sandstone, beyond which

were some beds of grey hardish rock, with nodules of sub-crystalline

limestone, the banks of the river being likewise covered with a crust, a

foot thick, of tufa. Some distance above this the red sandstones become

more scarce, the colour being generally brown or yellowish; grey clunch,

too, with bituminous laminae, was frequent.

“In one bank of brown

sandstone, a nest of coal with a sandstone nucleus was seen. The shape

was irregular and was about two feet long. It most probably was a

vegetable remain squeezed out of all semblance of its former shape. Over

this mass of sandstone there was again a good thickness of grey clunch,

and brown or yellow sandstone and conglomerate interstratified with red

and brown marl, all dipping gently to the S.E. Over these were some thin

beds of red sandstone with red marl, and a little beyond some hard light

brown or greyish yellow sandstone with small quartz pebbles. This rock

formed ledges stretching across the river, producing a fall of two or

three feet.

“About one hundred and

fifty yards above this, on the west bank of the brook, was some grey

clunch and shale, on which rested a bed of hard grey sandstone, eight

feet thick, covered by two or three feet of clunch and ironstone balls,

and two feet of soft brown sandstone, with ferruginous stains, on which

reposed a bed of coal three feet thick. The dip of these rocks was very

slight towards the south, in which direction the bank became low, as it

was also on the opposite side of the river, which prevented my tracing

the coal further ; neither was the bank above the coal high enough to

bring in any of the beds over it and thus give its total thickness,

since it is evident the position here seen may be only the lower part of

a bed instead of the whole. The quality of the portion thus exposed was

good, being a bright caking coal. The distance from the sea shore is

about eight miles j the only harbour, however, is that of St. George,

which is about twenty miles from this spot. A few very rude and

imperfect vegetable impressions were all I could see in any of these

rooks. Many of the gritstones in this section might turn out good

freestones. In the next brook to the east of the one I ascended, was

formerly a salt spring, which, however, I was assured, had lately become

quite dry ; but several of the little rills which I tasted in the

neighbourhood were brackish. As regards the extent of country occupied

by this bed of coal, or others which may lie above it, the data on which

to found any calculation are but few. If, however, the upper rocks

follow the course of the lower, without the intervention of faults and

irregularities, the tract so occupied would probably be an oval, forming

the centre of the country, bounded by the sea coast on the north and the

ridge of primary hills on the south. From the top of the highland at

Crabb's River, this ridge bounded the horizon at the distance apparently

of about twenty miles. Allowing half of this width to be occupied by the

lower beds, the tract yielding coal would probably be twenty or thirty

miles long by ten miles wide. Gypsum again appears once or twice in the

cliff between Crabb’s River and St. George’s Harbour. The north side of

St. George’s Bay, between Cape St. George and Indian Head, is occupied

entirely by beds of the magnesian limestone mentioned before, all

dipping at a slight angle to the N.N.W-, and thus passing under the

great mass of shales and gritstones which forms the country about Port

au Port.

“As regards the

external character of the district now under consideration, I have

already spoken of its physical geography, and have only to add a few

words on its agricultural capabilities. The coal formation, on account

of its alternate beds of marl and sandstone, and its low and undulating

surface, is everywhere admirably adapted for cultivation. On the south

side of St. George’s Bay, along the sea cliffs, on the hanks of the

rivers, or wherever the surface is drained and cleared of trees, it is

covered with beautiful grass ; and the few straggling settlers scattered

along that shore exist almost entirely on the produce of their live

stock. The aspect of their houses put me in mind of the cottages of

small farmers in some parts of England. There is every reason to believe

that the same fertility would be characteristic of the country round the

N. E. of the Grand Pond. The whole of the district, even the primary

hills, is covered with wood of a far finer description than the

generality of that on the east side of the island. Groves of tine birch

and juniper are scattered among the fir, and pines are met with here and

there in the interior of the country. On the bank of a brook between St.

George’s Bay and the Grand Pond, my Indian guide pointed out several

fine ash trees. The Bay of Islands, has, I believe, long been celebrated

in Newfoundland tor its timber ; and I can safely assert, that the Banks

of the Humber, as far as I ascended it, did not deteriorate in that

respect—every portion of the country being densely covered with fine

wood.”

Alexander Murray, Esq.,

in his Report of the Geological Survey of Newfoundland, in 1866 and

1867, says :—

“The coal formation is

probably the most recent group of rocks exhibited in Newfoundland

(excepting always the superficial deposits of very modern date, which

are largely made up of the ruins), and there may have been a time in the

earth’s history when it spread over the greater part of the land which

now forms the Island ; but a vast denudation has swept away much of the

original accumulation, and left the remainder in detached patches,

filling up the hollows and valleys among the harder and more endurable

rocks of older date, on which it was unconformably deposited. One of the

most important of these detached troughs or basins of coal measures is

in Bay St. George, where the formation occupies nearly all the lower and

more level tract of country between the mountains and the shores of the

Bay ; and another lies in a somewhat elongated basin from between the

more northern ends of the Grand and Deer Ponds, and White Bay; the

eastern outcrop running through Sandy Pond, while the western side

probably comes out in the valley of the Humber River, near the eastern

flank of the long range of mountains. There is reason also to suspect

the presence of a smaller trough of the same rocks, between Port-a-Port

and Bear Heail towards the Bay of Islands, the greater part of which,

however, is probably in the sea ; and from local information I received

from the Indians, as well as some residents at the Bay St. George, I th'

ik it not improbable that another trough of the formation may occur in

the region of the Bay of Islands.”

Captain Loch in his

report to the Vice Admiral, the Right Honourable the Earl of Dundonald,

in 1849, speaking of St. George’s Bay, says :—

“There are two hundred

resident planters in this Bay, who receive assistance in hands during

the fishing season from Cape Breton and its adjacent shores. Their

fishing usually commences a month or six weeks earlier than that on the

coast of Labrador. This year they began the 27th April. They fish

herring, salmon, trout, and eel, besides the cod. Up to the present date

(17th August) the catch has been 10,000 barrels of herring, 200 barrels

of salmon, and but a small quantity of cod. They employ about 200 boats

and 800 hands, and send their fish to the Halifax and Quebec markets

during the summer and fall. The fishings end about the 1st of October,

with the exception of the eels, which are caught in great quantities and

afford subsistence during the winter. They have bait without

intermission during the entire fishing, and use caplin, herring, squid,

and clams. The climate is usually dry and mild, and if their society was

under proper control, St. George's Bay would offer many inducements to

the industrious settler. The harbour is occasionally blocked up by ice,

but for no length of time, and is always open by the middle of April.

The inhabitants consist of English, a few Irish, and a number of lawless

adventurers—the very outcasts of society from Cape Breton and Canada;

and it is very distressing to perceive a community, comprising nearly

1000 inhabitants, settled in an English colony under no law or

restraint, and having no one to control them, if we except what may be

exercised through the influence shown by the single clergymen of the

Established Church, who is the only person of authority in the

settlement. I am told the reason why magistrates are not appointed, is

'n obedience to direct orders from the home government—it being believed

against the spirit of the treaty with France. Under these circumstances

I would recommend, either that a vessel-of-war should be appointed to

remain stationary in the harbour, or that the society should be forcibly

broken up and removed, for violent and lawless characters are rapidly

increasing, and neither the lives nor property of any substantial or

well-disposed settler are safe. Four cases of violent assault were

brought to my notice as having recently been committed upon parties—some

of whom were injured for life, and others nearly murdered ; and I was

sorry to understand the culprits had succeeded in escaping into the

woods upon the appearance of her Majesty’s ship.

“The cultivation of

grain has been commenced with considerable success. Wheat, barley, and

oats ripen well; and turnips grow particularly fine. Potatoes and garden

stuffs are cultivated also to a considerable extent. A large quantity of

fur is collected, but the trappers suffer great losses by the frequent

robbery of both traps and their contents.”

From Cape St. John

north to Cape Ray on the west, the distance is 398 geographical miles.

On this line of coast, the French possess the right by treaty, of

catching and drying fish, but are not allowed to make any permanent

erections, nor to remain longer than the time necessary to cure their

fish. Of course, all the residents are British subjects. According to

the returns in 1857, the population was as follows, on the west coast

principally :

1,647 Church of

England.

1,586 Church of Rome.

85 Wesleyans.

16 Free Church of Scotland.

3,334 Total.

There were 54

dwelling-houses, 1 Church of England, and 1 Roman Catholic. 1,508 acres

of land cultivated, yielding annually 1,204 tons hay; 40 bushels of

wheat and barley, 33 bushels of oats, 21,112 bushels of potatoes and

1,175 bushels of turnips. Of live stock, there were 87-‘5 neat cattle,

493 milch cows, 25 horses, 1,167 sheep, ami 310 swine and goats. Butter,

5242 lbs., cheese, 112 lbs., 453 yards of coarse cloth manufactured, 25

vessels engaged in the fisheries, 845 boats, carrying from 4 to 30

quintals ; nets and Seines, 2,354 ; codfish cured, 25,592 quintals ; 437

tierces of salmon, 17,908 barrels of herring, 13,609 seals, 1,391 seal

nets, 10,896 gallons of oil.

Regarding the moral

condition of the inhabitants of St. George’s Bay, the reader will be

able to gather some information from the following extract of a letter

from the Rev. Mr. Meek, Church of England Missionary, written in 1840

:—-

“I came to the place

five years since, as confessedly one of the most obscure, most

neglected, and most unpromising places in the island ; and, though I

have received in it many blessings, and though both myself and family

are, and have been, in the enjoyment of constant health, and though I

have seen at times cause for hope that I might be permitted with

acceptance and success, though less than the least of those who have

been entrusted with the commission, to ‘preach the Gospel to every

creature,’ to fulfil this blessed trust in this remote and uncultivated

spot, yet I find that I undertook no light or unanxious engagement; and

I confess that the last year and a half has been to me a season of

painful trial, as standing alone in the midst of surrounding evil,

which, not by power, nor by might, but by God’s spirit alone, can be met

or overcome; and I have been ready, like another Jonah, to flee from

proclaiming what is very unwelcome truth.

Owing to the peculiar

circumstances of the place, which, by treaty with the French, has

engaged to have no settlement in it, there neither is, nor can be, an}'

law or authority exercised ; consequently it is now become the

rendezvous of such as have no fear of God, and are glad to escape from

the control of man. You have, perhaps, heard of the wreck which occurred

here last fall, and some of the painful circumstances connected with it:

the parties concerned have, however, thus far escaped, and are here ;

and I should feel little trouble on their account, were it not that, in

connexion with others of like mind, they are leading the too-easily-led

people into such constant habits of drunkenness, revelling, fighting,

&c., that it must be manifest to you how painful is that duty which

constrains me to declare in such a place, that they who do such things

shall not inherit the kingdom of God ; yet this is my situation ; and

often with the sound of the midnight revel in our ears do we lie

sleepless, and mentally saying, ‘Woe is me that I sojourn in Mesech,

that I dwell in the tents of Kedar ! ’

“I am happy to say

that, after a good deal of trouble, the church is at length nearly

completed. It is one of the neatest outharbour churches in the island,

and is in general, especially in the winter, well attended; and, though

I have much to try and discourage, I have still much pleasure in

declaring, even to the worst, that Jesus Christ came into the world to

save sinners.

“The school continues

much as usual; it cannot be large till the settlement enlarges. About 40

children are usually present in the summer, and 50 in the winter. Of

course there is considerable improvement in the ability to read and

write, where no means were ever afforded for enabling any to do so; but

I regret that the constant bad examples around, and the want of parental

control, are far from being productive of good on the young."

In 1848, Mr. Meek

agfain writes:

“We passed, in many

respects, a trying winter: our neighbours were as poor as ourselves.

There were no stores or ships to go to; the poor Acadians were living

entirely upon eels, obtained through the ice, without bread or flour, or

anything else, and there were many things to depress and discourage; but

to school and to church we, without interruption, went, and, I trust,

have been thus far enabled to continue the unvarying testimony, that ‘

Neither is there salvation in any other, for there is none other name

under heaven given among men, save that of Jesus Christ alone, whereby

they must be saved.’ Yet here, alas, too, we have much to discourage—an

insensibility, an apathy, an almost opposition in many. Of one, indeed,

the chief fiddler hitherto at the dances, we have pleasing hope that

there is some good thing toward the Lord God of Israel. He has long

beten a regular and serious worshipper in our congregation, but now he

has, and that in spite of urgent solicitation and offers of some value,

renounced for ever his former employment, and, as far as he knows it,

determined to pursue the narrow way; but, in general, it is uphill work.

“You would be greatly

surprised at the peculiar circumstances of this strange place: they are

unlike every other even in Newfoundland. There is a great deal of abject

poverty, mixed up with a fondness for dress and appearance, that is very

painful. White veils and parasols adorn females who are seen at the

herring pickling ; indeed, there is scarcely an idea of any distinction

in society, and it is almost impossible to impress the folly and

absurdity of such contradiction to all that is becoming on them. Yet

these ladies are found at the balls, to which they are so much attached,

mixed up with Indians, Acadians, French, little children, and an

indiscriminate collection of all sorts and conditions. Oh, how we are

often pained and tried ! but never so much, T think, as on last New

Year’s Day, when, after I had preached the most solemn and pointed

sermon I could write (and I would send you the M.S. but for the expense

of postage), the congregation went out of church to a dance, which

continued till twelve at night, when, being Saturday, it was

discontinued. Surely I slept not that night, and went to church next day

with a heavy heart, and a cry, ‘Woe is me, that I am constrained to

dwell with Mesech!’

“We are greatly

indebted to Miss Hay don, of Guilford, for a box of clothing, partly for

the poor, and partly to relieve the wants of my own family, in

consequence of last summer’s catastrophe. It serves to reassure and help

us on in our solitary course, that friends so far off remember and

sympathise with us; and we hope that, upheld by their prayers, we shall

be enabled to hold on our way, and witness a good confession, and that

still we shall continue in church and school to teach and preach Jesus

Christ.

“It will be a long time

before we can hear from you again, or from anybody : remember how much

we need your prayers when we sit down alone in this solitude, surrounded

by so many who know not God, and obey not the Gospel of our Lord Jesus

Christ. The cold we can bear, the snow we can wade through, but the

dreadful apathy and insensibility around freezes up the soul. Alas, how

different is the missionary’s life to what the youthful listener in a

London public meeting imagines ! and nowhere, I think, is it more tried

than in Newfoundland. But I must commend myself, Mrs. M., our five

children and our charge, once more to your prayers and sympathies. I

have been more than nineteen years at work here and am forty-seven years

of age; I feel that the night cometh, that I have a trust to fulfil, and

an account to give, but He that has helped me hitherto will help me all

my journey through.”

The Rev. Mr. Meek

removed from St. George’s Bay to Prince Edward Island, and was succeeded

in the Mission by the Rev. Thomas Boland.

“In March, 1856, he

went to visit a parishioner a short distance from Sandy Point, the place

of his residence; and, not returning when expected, search was made for

him, and he was found dead within a mile of his own house. It is

presumed, that having incautiously gone alone, he had lost his way in a

drift; and, yielding to cold and fatigue, had sunk into that fatal sleep

in which the vital powers are soon extinct.

“The Rev. Thomas Boland

had, before his ordination, been for several years a Scripture Reader in

the Parish of Whitechapel, and was highly commended to the Society by

several clergymen to whom he had been favourably known in that part of

the town. The Rev. W. W. Champnevs, in particular, testified to ‘ his

genuine piety, decided ability, and the soundness of his views.’ He went

to Newfoundland in 1849. The obituary notice characterises him as a

person of much learning, ability, and zeal; and adds, tha this ministry

appeared to be much blessed in the remote settlements—first of Channel,

and afterwards of St. George’s Bay, to which he was sent as the

Society’s Missionary by the present Bishop of Newfoundland, by whom he

was ordained both deacon and priest.”

The Rev. H. Lind

succeeded Mr. Boland in the Mission of St. George’s Bay. The following

incident is related by Mr. Lind:

“An Indian mountaineer

had been hunting, and had killed a deer, the skin of which he had

wrapped about his person, when a bear met him, and, no doubt, tempted by

the smell of blood, knocked him down, and would have torn him to pieces,

when his daughter, seeing the danger of her father, crept quietly to

him, and, at the risk of her own life, took his hunting-knife from his

belt, and plunged it into the body of the infuriated beast, which fell

dead at her feet, and thus liberated her parent.”

In 1849, Bishop Field

made an episcopal visit to this part of the Coast. The following is an

extract from an account of the Bishop's visit:—

“Leaving

Port-aux-Basques the same evening, the Church Ship was anchored in

Codroy Boads earlv on Thursday morning, July 26th. Here two services

were held in the house of a respectable planter; and in the evening

service (at 6 o’clock) several children were admitted into the Church.

These people had seen no Clergymen among them since the Bishop’s visit

four years ago. Between the services the Bishop, with two of his Clergy,

went over to the great Codroy River, (six miles) and there baptized

three children. The Bishop then returned to hold the promised service at

Codroy, but the Clergy proceeded six miles further to the Little River.

Fifteen years ago Archdeacon Wix visited these settlements, and baptized

there ; but no Clergyman has been seen, no service of our Church

performed there since. The worldly circumstances of the inhabitants are

in direct contrast to their spiritual and religious condition, for they

enjoy the produce of the land as well as of the sea in abundance. They

have numerous flocks of fine cattle, and grow various kinds of corn with

a little labour, and a large return.

“The wind being fair it

was thought prudent to proceed the same night to Sandy Point (Mr. Meek’s

mission), at the head of St. George’s Bay. At the time of the Bishop’s

visit to this mission last year, Mr. Meek had unfortunately just sailed

for St. John’s. On this occasion he was prepared for and anxiously

expecting his Lordship.

“The Church Ship

remained in this Harbour three days, and on Sunday the Bishop celebrated

the Holy Communion in the morning, and gave Confirmation in the

afternoon service

Four long years had

elapsed since either of those Holy Services had been celebrated in this

settlement, and years of peculiar trial to the Missionary and his flock.

During the Bishop’s stay, the Wellesley, Flag Ship, with the Admiral,

Earl Dundonald, on board, arrived, and remained two days in the harbour.

“On Tuesday, July 31st,

the Church Ship sailed for the Bay of Islands, which was reached and

entered in safety early the following day. Here is the place, and here

the people whose condition, as reported by Archdeacon Wix fifteen years

ago, excited so much commiseration. It may readily be supposed that as

no Minister of Religion, and no teacher of any name or persuasion, had

visited them in the long interval, their moral state can only have

become more wretched and degraded. The people are settled in most

picturesque and fertile spots on either side of the Humber Sound, which

for beauty of scenery, size and variety of timber, and richness of soil,

is perhaps the most favoured locality in Newfoundland. The condition of

the inhabitants in moral and social circumstances stands in strong and

unhappy contrast; and they do not generally appear to know even how to

turn to account their natural advantages. Several families were found in

a state of deplorable destitution. Others, more prosperous or more

careful, were not less ignorant and unmindful of any concerns or

interests beyond the provision for this life. The Church Ship remained

the rest of the week, four days, in the Bay; and every day was fully

occupied in visiting the people from house to house, baptizing and

admitting into the Church the children under fifteen years of age, and

giving to young and old such exhortation and advice as seemed best

suited to their unhappy state.

“It was a melancholy

thing to leave them to their former darkness and destitution, but there

was too much reason to expect that others would be found in a similar

condition, along the shore.

“The Church Ship left

the Bay of Islands at midnight, on Saturday, August 4th, and at 9

o’clock the next morning called off a settlement at Trout River, were,

without coming to anchor, the Bishop and his Clergy celebrated Divine

Service on shore. Morniug Service was celebrated on board after the

Bishop’s return. By four o’clock the Church Ship was anchored in Rocky

Harbour, at the mouth of Bonne Bay, and, after holding Evening Service

on board, the Bishop and Clergy went on shore, and baptized and received

into the Church a large number of interesting children :—and thus four

full Ser vices were celebrated on that Sunday, two on board, and two on

shore. No Clergyman of our Church had ever before visited these

settlements: but in each of them the patriarch, or head of the

settlement, was an Englishman, and could read, and hail brought and used

both his Bible anil Prayer-book, and the difference, in their favour,

between them and their neighbours at the Bay of Islands, was very

perceptible.

“Monday, August C.— The

Church Ship reached Cow Cove, another settlement never before visited by

a clergyman, and too much resembling in moral misery and degradation the

Bay of Islands. On the Tuesday such religious services were performed as

were required, and could properly be allowed under the circumstances of

the people. The settlements of Cow Harbour, Bonne Bay, Trout Cove, and

Bay of Islands, would together afford abundant occupation for a diligent

and devoted Missionary. They number at least three hundred souls.

“Wednesday morning,

August 8.—The shores of Labradoi came in sight, and the same evening the

Bay of Forteau again saw and received the Church Ship, according to

promise given last year.

“Thursday, August

11th.—The Bishop with his whole party visited L’Anse Amour and L’Anse a

Loup, and on the following day consecrated a grave-vard in the first

named settlement. Here the Rev. Mr. Gifford was introduced to his

mission, and was most kindly welcomed by Mr. Davies, and provided

immediately with a comfortable lodging. It was the Bishop’s wish,

however, that he should visit some other chief settlements in his

mission in the Church Ship, to have the benefit of a proper

introduction.

“Saturday, August

11.—The Church Ship sailed to Blanc Sablon, where the Messrs. Do

Quetetville, of Jersey, have a large establishment. Here a small river

divides the dependencies of Newfoundland on this coast from Canada, and,

of course, limits the Bishop’s Diocese. It was said to be the first

limit or end of his Diocese his lordship ever saw. In a store kindly

furnished by the agent (who seemed desirous to promote in every way the

objects of the Bishop’s visit), divine service was celebrated twice on

Sunday, August 12. The Holy Communion was administered. The Bishop

preached in the morning, and Mr. Gifford in the afternoon. The

congregation was large on each occasion, and consisted almost entirely

of the men connected with the establishment, and employed on the room.”

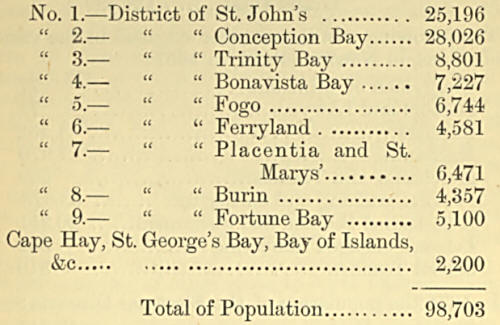

Recapitulation of the

Population of the Districts, 1849 :—

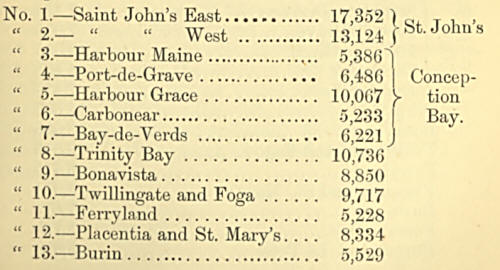

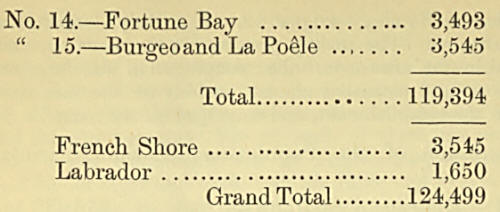

Population of the

Districts in 1857 :—

The following was the

number engaged in the various professions, in Newfoundland, in 1857 :

Clergymen or

Ministers............... 77

Doctors and Lawyers...................... 71

Farmers............. ......................... 1,552

Mechanics. . ................................ 1,970

Merchants and Traders...................... 689

Persons catching and curing fish......... 38,578

Able-bodied Seamen and Fishermen...... 20,311

Persons engaged lumbering................ 334

School Teachers ........................... 310

In 1874 the population

of the Electoral Districts:—

St. Johns,

East.-............................. 17,811

St. Johns, West.............................. 12,763

Southern Division...................... 7,174

Port-de-Grave............................ 7,918

Harbour Grace.......................... 13,055

Carbonear.................................. 5,488

Bay De Verds........................... 7,434

Trinity....................................... 15,667

Bonavista.................................... 13,008

Twillingate and Fago................... 13,643

Ferryland................................... 6,419

Placentia and St. Mary’s ................ 9,974

Burin.......................................... 7,678

Fortune Bay................................... 5,788

Burgeo and La Poele.................... 5,098

Total..............148,919

French Shore 8,651

Labrador 2,416

The census taken in

1869, show the following returns: Population, 146,596, consisting of,

Catholics, 61,040; Church of England, 55,184; Congregationalists, 338;

Wesleyans, 28,900; Presbyterians, 974; other denominations, 10. The

number of churches was 235. No less than 136,378 of the population are

returned as born in the Colony. Of the children, 16,249 are reported as

attending school, and 18,813 as non-attendants, but this would include

many of very tender years. The census also shows 37,259 to be engaged in

the fisheries, 20,617 as seamen, and 1,784 as farmers, while 99 are

clergymen, 24 are lawyers, 591 merchants, and 2,019 mechanics. The land

under culture amounted to 41,715 acres; the growth of turnips to 17,100

bushels; of potatoes, to 308,357 bushels; of other roots, to 9,847

bushels; of hay, to 20,458 tons; and of butter, to 162,508 lbs. The

vessels numbered 986, with a tonnage of 47,413 tons; boats, 14,755; nets

and seines, 26,523: seal nets, 4,761; persons engaged in the fisheries,

37,259; and seamen, 20,647. The horses numbered 3,764 ; horned cattle,

13,721; sheep, 23,044; goats, 6,417; and swine, 19,081. The product of

the fisheries was given in the census of 1869 as follows:—Cod, 1,087,781

quintals; salmon (cured), 33,149 tierces; herrings 97,035 barrels; other

fish (cured), 10,365 barrels; fish oil, 840,304 gallons; and seals,

333,056. The manufactures, on the other hand, amounted only to $72,675

in value.