|

ON THE WARPATH.

War in the congenial

occupation of the red man as it is the delight of the white man. On the

field of battle there is an outlet for ambition, and courage is seen to

advantage. Every nation has its distinctive uniform and implements of

warfare as well as its military tactics, and the red race is not lacking

in these elements of pride and strength. The rude flint-headed arrow

gave place to the flint-lock gun, and this to the later inventions of

civilized life, until to-day the natives of the plains are well armed

with Snider rifles, and boast of their prowess in battle. During the

second Riel Rebellion the Government stopped the sale of ammunition to

the western Indians, •and instead of resorting to the flint arrow-head,

they made the heads of their arrows from iron hoops. I have seen the old

men in the camps busily engaged in this work while the young men were

absent as spies.

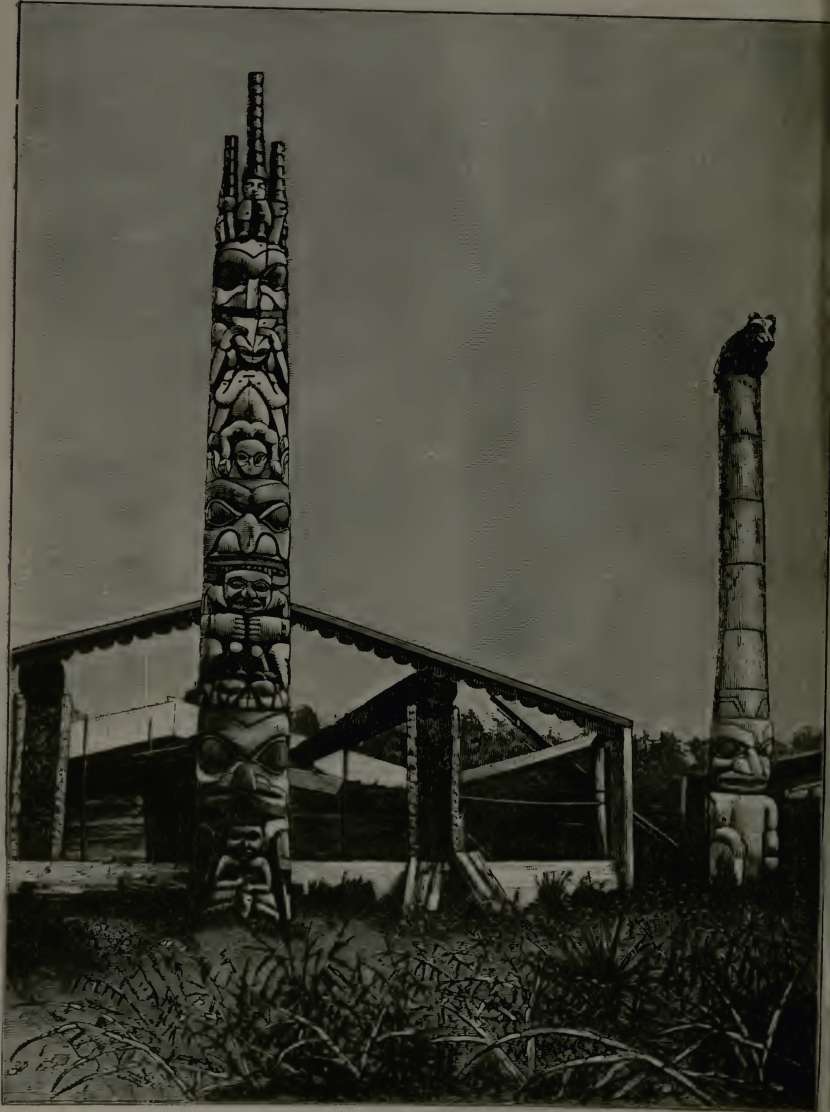

Flint arrow-heads have

been found in great abundance in the Province of Ontario, less

frequently in Manitoba and the Territories, and seldom have they been

discovered in British Columbia. Only one specimen of a chipped

arrow-head or spear-head having been found on the Queen Charlotte

Islands, and the Haidas, to whom it was shown, expressed surprise, as

they said they had never seen or heard of such a thing before. Instead

of donning bright colored garments to distinguish them in the field of

battle, every vestage of clothing is discarded except the breech-cloth,

moccasins and war bonnet. The warrior paints his body in a fantastic

fashion, and there is something appalling to the eye of civilized man on

beholding a body of painted savages. The war paint is significant. The

western Indians fought single-handed on the prairie under the direction

of the war chief or leader of the war party, spending no time in the

erection of works of defence; but upon the plain, in a river bottom or

ravine, or in any place where the combatants met they engaged in battle.

In the eastern provinces it was different, as the natives erected strong

earthworks of defence, where they were safe from the attacks of their

foes.

Parkman, basing his

statements upon Lafitau, says, in reference to the works of defence

erected by the Iroquois: "Their dwellings and works of defence were far

from contemptible, either in their dimensions or in their structure; and

though by the several attacks of the French, and especially by the

invasion of De Nouville in 1687, and of Frontenac nine years later,

their fortified towns were levelled to the earth, never again to

reappear ; yet, in the works of Champlain and other early writers, we

find abundant evidence of their pristine condition. Along the banks of

the Mohawk, among the hills and hollows of Onondaga, in the forests of

Oneida and Cayuga, on the romantic shores of Seneca Lake and the rich

borders of the Genesee, surrounded by waving maize fields, and encircled

from afar by the green margin of the forest, stood the ancient

strongholds of the confederacy. The clustering dwellings were

encompassed by palisades, in single, double or triple rows, pierced with

loopholes, furnished with platforms within for the convenience of the

defenders, with magazines of stones to hurl upon the heads of the enemy,

and with water conductors to extinguish any fire which might be kindled

from without. The area which these defences enclosed was often several

acres in extent, and the dwellings ranged in order within were sometimes

more than a hundred feet in length."2 The plan

of the Iroquois villages was usually circular or oval, and in one

instance Frontenac found an Onondaga village built in an oblong form,

with four bastions, having a wall formed of three rows of palisades, the

outer row being forty or fifty feet high. The bastions were doubtless

erected upon the advice of some European friend.

War was declared by a

harangue to the assembled natives and the delivery of an axe, from which

arose no doubt the figurative expression of "digging up the hatchet." A

painted hatchet was sometimes used to express strong determination to

fight, and to notify to their enemies their bitter enmity and resolution

to destroy. It is the object of war to destroy, and the red man will

seek to gain the complete overthrow of his foes by any strategy, without

incurring any needless risks. He believes that all means are honorable,

and he will strive to circumvent and subdue his adversary by any kind of

artifice.

The causes of war

between the native tribes and between the red and white races are

similar to those among civilized races. The invasion of territory,

hunting upon the grounds claimed by another tribe, the killing of a

native in cold blood, the breaking of treaties, and the compulsory

removal of the Indians (as in the case of the Nez Perces), the wholesale

robbery of the Indians by the agents of the Government, and their harsh

treatment by white men, the hatred of the tribes and feuds among

themselves, unfulfilled promises by Government officials and the bad

influence of immoral white men. The Minnesota and Custer massacres and

the Riel Rebellion can be traced to some of these causes. War is not a

mere pastime even among savages, for there must be some pretext, and

sometimes it is a poor one, before the tribes will go on the warpath

Among the western

tribes of our Dominion there are peace chiefs and war chiefs, the former

performing the duties of civil head of the tribe, and the latter

assuming the responsibilities of his office in times of war. This

important military officer is elected on account of his bravery and

success, and his influence is almost unlimited among his people. White

Calf, the war chief of the Blood Indians, is a typical Indian, hating

the language, customs and religion of the white men. As lie sees the

gradual decrease of his people, and their dependence upon the Government

for support since the departure of the buffalo, and the encroachments

and haughty spirit of the white men, remembering the freedom of the old

hunting days and the valor of the young men, and seeing them transformed

into a band of peaceful farmers, he mourns the loss of the martial

spirit and pristine liberty, and longs for the return of the heroic

days. The war chief is the native general, yet he is not absolute, for

even a chief must obey the laws of they tribe.

It was necessary to

secure allies to assist the tribes in a general war, and for the purpose

of securing them, messengers were sent by the eastern tribes to the

distant tribes, bearing the long, and broad war-belt of wampum and the

red-stained tomahawk. Visiting each tribe, the sachems and old men

assembled in council, when the chief of the embassy threw down the

tomahawk on the ground and delivered the speech which he had been

instructed to make. When the assemblage were in favor of war the belt of

wampum was accepted and the tomahawk snatched up as a token of their

pledge. The natives, of the west sent their messengers with tobacco, and

upon addressing the council of the tribe visited, when the warriors

decided to unite in war the tobacco was accepted. Red Crow, the peace

chief of the Blood Indians, refused the tobacco offered him by the

messengers of the rebels during the Riel Rebellion, and when Pakan,

chief of the Crees, was importuned by the messengers of Big Bear to

accept the tobacco and join the rebels, he shot one of the messengers

dead. Large war parties were not as likely to be successful as small

bodies of men, owing to their lack of discipline, individual liberty and

mode of action. The war chief could not punish those who wished to stay

at home, as they were essentially volunteers in the service, and were

bound to him by a moral tie and an interest in the enterprise. Pride and

jealousy sometimes broke out in feuds among his followers, or among the

different tribes engaged as allies, and then desertions were frequent.

The native warrior hates subordination, and delights.

to gain power by means

of personal bravery, so that his individuality is a burner to concerted

action, and sometimes before the country of the enemy is reached discord

has divided the bands, and a remnant of the host is left to contend

against the foe.

When war has been

declared the warriors spend a few days singing war songs, boasting of

their valor, calling upon their gods to help them, and getting their

accoutrements in readiness. They engage in a war dance, feasting,

dancing, singing and praying; and then with their bodies painted they

advance toward the enemy's country regardless of order. Usually they

depart at night. If the distance is long they will travel by day and

rest at night, but should there be any danger they will travel

cautiously at night and rest during the day. The western natives always

take care to go upon the warpath when there is no snow on the ground,

lest they should be tracked, and in a season when there is good feed for

their horses. If there is any chance of defeat they will make

arrangements for the safety of their women and children. There is no

likelihood of another Indian war, as there is no refuge for the helpless

folks of the camps.

Some of the natives are

adepts at tracking on the prairie, being able to tell by signs around

the camping place the number of white men and Indians in the party,

whether they are hostile or' friendly, and even the names of the persons

known to them. They are experts also at concealing their tracks by

crossing, recrossing and returning upon the prints made by the moccasin

or horse-hoof, so as to baffle and elude their pursuers, even when the

snow is on the ground. The Iroquois chiefs wore tall plumes, and arrayed

themselves in times of war in bucklers and breastplates made of cedar

wood, covered with interwoven thongs of hide; and the Hurons carried

large shields, wore greaves for the legs and cuirasses made of twigs

interwoven with cords. The scalp lock is a thing of the past among the

western warriors, if they ever wore it, and defensive armour is unknown

to them. Their only defence is the song and divination of the medicine

man and the amulet worn on the person.

Stealing cautiously

into the camp of the enemy, the single warrior enters a lodge, stirs the

dying embers of the tin4 and quietly scans the

sleeping occupants. Suddenly dealing a death-thrust to each of his

victims and securing the bleeding scalps, he hurries from the scene of

destruction and, elated at his success, is lost in the darkness. From

our standpoint of military virtue there is no exhibition of courage, but

rather an evidence of cowardice in such a dastardly feat; but the code

of honor 011 the plains agrees with their method of fighting, which

implies a wariness and coolness in the presence of danger and the defeat

of their enemies by stratagem.*

Rushing suddenly upon

their foes in battle, the war-whoop is given, which sends a deep thrill

of excitement through the camp. White men and women who have heard it

when attacked by the Blackfeet have told me, that when once it is heard

it will never be forgotten. It strikes terror to the hearts of the

unprotected, and men brace themselves for battle as women seek a place

of refuge.

It was the custom of

the natives to retain some of their prisoners to find pleasure in

mutilating them, and in early Canadian history, there are sad tales of

cannibalism, when the Indians, even in the presence of the French

soldiers, killed their enemies, cooked and eat their flesh. Sometimes

they were slain after enduring excessive tortures, but after their

vengeance was appeased they would spare the remainder, and distribute

them among the tribes, 01* allow them to be adopted by some of the

families. A young man would sometimes be chosen by a native to supply

the place of a dead son, and even a woman might obtain a husband for the

one deceased. The Blackfeet and Crees have always spoken with intense

abhorrence of cannibalism, and whenever it has been discovered, as it

has in one or two instances, through starvation, the perpetrators have

been ostracised. It is singular that those children who have been

captured and brought up in the camp have become deeply attached to their

foster parents, and have loved intensely the customs of the people, so

that it was well-nigh impossible to induce them to return to civilized

life or the home of their relations. John Tanner, the scout, who spent

many years in Michigan, Western Ontario and Manitoba returned to his

savage haunts after tasting the pleasures of civilized life. The

fascination of forest and prairie and the wild ways of the red men was

stronger than the joy and comfort of civilization for this strange man

as it has been for other men in later years. Adoption among the Crees

lias been practised within the knowledge of men still living, as in the

case of James Evans, the missionary. Having gone upon a missionary tour,

his native companion accidentally shot himself, and the missionary

returned to the family of the young man, and was adopted in his place,

so that he was always recognized as the son of the parents of the

deceased.

In times of peace, as

well as war, the natives employ the art of signalling, in which they are

very skilful. It is possible to see a long distance upon the prairie,

and it is easy to send communications in times of distress. By means of

lighted arrows shot through the air at night, a message can be sent and

understood twenty miles away. The smoke of the fire can be ,so directed

that it will relate its own story to anxious watchers. During the day

the solitary rider will pace backward and forward upon a high bluff, or

ride in a circle, or perform well-understood and significant evolutions.

The single warrior will tell his tale through the sign language with his

hands, or by means of his blanket, or again with a small looking-glass,

he will send a flash of light across the plain, which will be easily

interpreted by his people. This native system of telegraphy enables the

red men to remain secluded, and yet keep one another informed on matters

affecting them in times of war, by means of scouts.

When the war expedition

is ended and the warriors return home, messengers are despatched when

they are approaching the camp, to inform the people of their success.

The war-whoop is given a certain number of times corresponding to the

number of scalps taken, and with a song of victory they enter the camp.

The old men, women and children go out to meet them, and with sad wails

from the women who have been bereft of husbands, fathers, sons and

brothers, and shouts of victory on the part of those who have not

suffered, the party is honored on account of the success of the

enterprise. Since the advent of the white settlers the war expeditions

have been few, and have only been undertaken to recover stolen horses.

Silently they departed, and then the party was composed of only a few

young men. Eight young men started about 1888, for the home of the Gros

Ventre Indians in the south, to recover some horses which were stolen

from the Reservation of the Blood Indians. Two of them became separated

from the others, and these alone returned, the rest of them being slain

and scalped by their enemies. There was great excitement in the camps

for a few weeks, but the Government used its influence, and by a wise

compensation to the bereaved families, a war between the two tribes was

averted.

It was the custom of

the Algonquins to cut off the heads of their enemies, which they carricd

home as trophies; and among the Indians of Nova Scotia the head was cut

off and carried away and afterward scalped. The practice of scalping was

in existence before the French arrived in Canada, as Jacques Cartier, in

1535, saw five scalps at Quebec, dried and stretched on hoops. Sometimes

dead bodies left on the field of battle were scalped. In their anxiety

to secure scalps, the conquerors did not always wait until their victims

were dead, and it sometimes happened that they were only wounded

slightly. Some of these persons have lived after they were scalped,

which proves that scalping did not always end in death. The object of

securing scalps seems not to have arisen from cruelty, but rather to

give evidence of success in war. The Indian might boast in the camp of

his bravery, assuring his auditors of the number of men he had slain,

but there were always some who were suspicious, and believed not the

statements of the young warrior. As it was not always convenient for him

to secure the head of his enemy, and he could not well preserve it

afterwards, the easiest way for him to substantiate his assertions was

to take the scalp, which he could show to his people.6

1 have seen the lodges of half-breeds and Indians painted, having the

life story of their owners depicted upon them and the scalp-locks

fastened to the outside, which were tangible proofs of the military

prowess of the occupants. One of my friends gave me a scalp, when it was

no longer customary to hang them on the lodges, and this scalp may still

be seen in the museum of the Canadian Institute, Toronto. Some of the

eastern Indians were accustomed to burn their enemies at the stake, but

I have never learned of this being done by the natives in the west.

During the war between

the English and the French, when the Indians were engaged as allies,

bounties were offered by the civilized governments for scalps, although

more humane treatment afterward prevailed. Indeed, during this war some

of the white soldiers outstripped the red men in their anxiety to secure

the scalps of the Indians. It was an advantage to feign insanity among

the natives who are superstitious on this matter, believing such persons

as are so afflicted to be special favorites of the gods. Heckewelder

mentions the case of a trader, named Chapman, who was made prisoner by

the Indians at Detroit. Having determined to burn him alive, he was tied

to the stake and the fire kindled. One of the Indians handed him a bowl

of broth which was made scalding hot so as to give pleasure to the

onlookers by the increased tortures of their victim. When the poor man

placed it to his lips it produced intense pain, and in his anger he

threw the bowl and its contents into the face of his tormentor.

Instantly the crowd shouted, " He is mad ! he is mad!" and as speedily

as possible the fire was extinguished and the sufferer was set at

liberty. Believing in destroying their enemies in any manner, the

natives resorted to treachery, getting inside of forts under the

pretence of friendship, and even giving pledges of protection in time of

war, only to kill their foes when they had secured the advantage. There

are some notable examples of honorable dealing by chiefs and warriors,

who would not stoop to such acts of meanness; but when exasperated the

average Indian will not in war abide by his promises, and he cannot be

trusted.

The scalp dance is a

significant native institution, which has passed away. The scalp having

been prepared according to the native ceremonial, was fastened to a

pole, which was carried through the camp, the people dancing around it,

singing wildly and uttering unearthly yells.

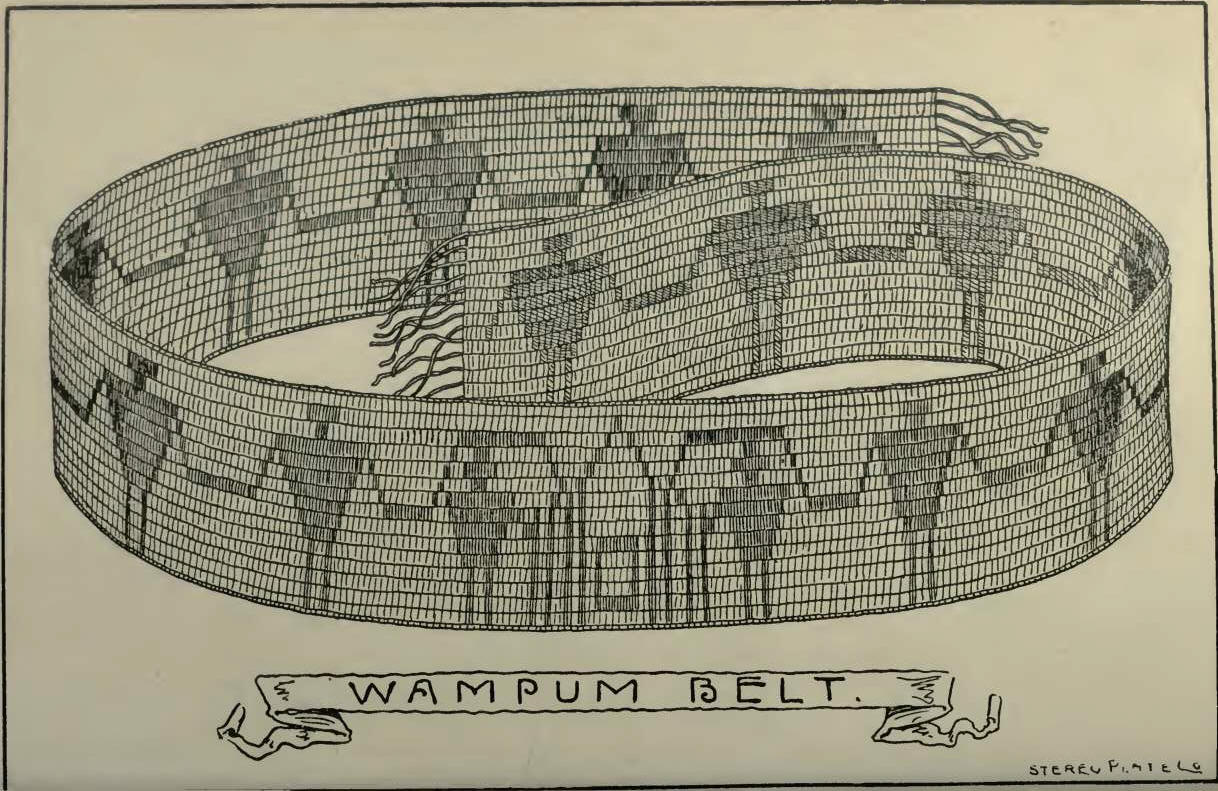

Upon the declaration of

war black wampum belts were given by the messengers to those allies who

agreed to fight, and these were pledges of unity in war, and when

treaties of peace were made, belts made of white wampum were given and

accepted as solemn pledges. Wampum was used by the Indians of the

Eastern Provinces, especially the Six Nation Indians, but is unknown

even in the traditions of the prairie tribes. At first the wampum was

made of porcupine quills dyed, then of colored pieces of wood, again

from the thick and blue parts of clam shells, and finally of glass

beads. It was used as money by the tribes and as a pledge in solemn

transactions. As late as 1844, it was extensively manufactured by the

Indian women of New Jersey, who sold it to the country merchants at

twelve and a half cents a string, The wampum shell beads were strung on

hempen strings about a foot in length each, and one woman could make

from five to ten strings a day.

At a great assembly

held on July 12th, 1644, at Three Rivers, in the open square of the

fort, presided over by the Governor-General, a treaty of peace was made

between the Indian tribes themselves, and between the Indians and the

French. There were present representatives from the Iroquois, Algonquin,

Montagnais, Huron, Attikamegues and Mohawk tribes. In the middle of the

open space the Iroquois planted two poles, having a cord stretched

between them, upon which were placed seventeen wampum belts. Each belt

was used for a specific purpose. Kiotsaeton, the famous Iroquois orator,

holding the first belt of wampum, and with many significant gestures and

an impressive

speech, presented it to

Onontio, the Governor-General, for rescuing Tokrahenchiaron from the

Hurons. The second belt was fastened around the arm of Couture, a young

Frenchman, who was a prisoner among the Iroquois, as a pledge that he

was set at liberty ; the fourth belt was a pledge of peace between the

Iroquois and Algonquins : the fifth belt drove the enemies' canoes away

: the sixth smoothed the rapids on the way to the country of the

Iroquois: the eighth was to build a road ; the tenth belt, larger and

finer than the other belts, proclaimed peace between the French,

Algonquins and Mohawks, and as the orator addressed the assembly he took

a Frenchman and an Algonquin and bound their arms together with the

belt. The eleventh belt promised hospitable board to their friends, and

this part of his speech closed with the suggestive sentences, " We have

fish and game in plenty; our forests teem with stags, moose, deer, bears

and beavers. Drive away the filthy hogs that defile your houses and feed

only on filth." The twelfth belt banished all suspicions of

deceitfulness which were ascribed to them, and as the orator beat the

air, as if to scatter and drive away the clouds, he cried, " Let the sun

and truth shine everywhere." The thirteenth and fourteenth belts were

pledges of peace between the Iroquois and Hurons : the fifteenth was a

justification of their treatment of the missionaries, Jogues and

Bressani; and the seventeenth was a present from the mother of

Honateniate, who had been kept as a hostage by the Governor-General,

requesting him to set her son free.

The pipe of peace has

been smoked in recent times by representatives of the tribes of the

plains as a token of peaceful relations and unity, the hatchet has been

buried by the eastern tribes as a pledge of friendship, and with the new

conditions of existence, the progress of settlement upon the prairies,

and the growing sentiments of kindness and justice, there can never

again fall upon our ears the war-whoop of the savage or the boom of

cannon in the Indian camp.

RUNNING THE GAUNTLET.

The arrival of

prisoners in the camps is received with great rejoicings on account of

the victory, and indignities are heaped upon them by the old men, women

and children, and sometimes they are subjected to excessive tortures.

When they are tried for their lives by the council, and they are not

adopted by any persons in the camp, or are not distributed among the

tribes, but are doomed to die, they may be burned at the stake, as was

customary among the Iroquois and other eastern tribes, or speedily

despatched by the tomahawk. Desirous of relieving the monotony of their

lives and obtaining pleasure at the expense of the sufferings of the

captives, a chance was oftentimes given them of saving themselves by

"running the gauntlet." Hunter, in the "Memoirs of his Captivity," says

that in every native village there was a prisoner's place of refuge,

designated by a post uniformly painted red in times of war, planted near

the council-house. Two rows of women and children armed with clubs,

switches and missiles were stationed within a short •distance from the

post, and the prisoners were compelled to pass between them. If they

were able to run quickly and arrive in safety at the post, they were

placed in charge of guards until the council decided their fate. Some

were saved and became members of the tribe, but others were condemned to

death. Sometimes the captives were'bound hand and foot, and burned with

pieces of touchwood, or whipped severely, A brave man would taunt his

captors, daring them to do their utmost to injure them, and with the

death song on his lips would teach them how to die. As the prisoners ran

between the ranks, it sometimes happened that some of them would

intentionally slacken their pace, that they might die on the way,

knowing that a more cruel fate awaited them. "The return of the Kansas

with their prisoners and scalps was greeted by the squaws, as is usual

on such occasions, by the most extravagant rejoicings ; while every

imaginable indignity was practised on the prisoners. The rage of the

relict of Kiskemas knew no bounds; she, with the rest of the squaws,

particularly those who had lost any connections, and the children,

whipped the prisoners with green briars and hazel switches, and threw

firebrands, clubs and stones at them as they ran between their ranks to

the painted post, which is a goal of safety for all who arrive at it

till their fate is finally determined in a general council of the

victorious warriors."9 The custom of

compelling prisoners to run the gauntlet was enforced at two, if not all

the mission villages in Canada down to the end of the French domination.

Parkman says, "The practice was common, and must have had the consent of

the priests of the mission." When Hannah Dustan and her nurse, Mary

Neff, were taken prisoners by the Abenakis, as they journeyed toward a

native village, after Hannah's infant had been dashed to death against a

tree, the warriors amused themselves by telling the women that when they

arrived at their destination, they would be stripped and made to run the

gauntlet.

The Iroquois sometimes

led their prisoners through the tribes embracing their confederacy,

compelling them at every village to undergo this torture, and seldom did

they escape without the loss of a hand, finger or eye, and many of them

perished as they ran toward the goal. General Stark, when a young man,

was captured by the Indians, and made to run the gauntlet. As he ran, he

knocked down the nearest warrior, snatched the war-club from his hands,

and used it so dexterously that he reached the goal in safety, while his

companion was nearly beaten to death. During the Pontiac conspiracy some

prisoners were taken and forced to follow this Indian custom. Parkman

says: "The women having arranged themselves in two rows, with clubs and

sticks, the prisoners were taken out, one by one, and told to run the

gauntlet to Pontiac's lodge. Of sixty-six persons who were brought to

the shore, sixty-four ran the gauntlet and all were killed. One of the

remaining two, who had had his thigh broken in the firing from' the

shore, and who was tied to his seat, and compelled to row, had became by

this time so much exhausted that he could not help himself. He was

thrown out of the boat and killed with clubs. The other, when directed

to run for the lodge, suddenly fell upon his knees in the water, made

the sign of the Qross on his forehead and breast, and darted out into

the stream. An expert swimmer from the Indians followed him, and having

overtaken him, seized him by the hair, and crying out, ' You seem to

love water, you shall have enough of it,' he stabbed the poor fellow,

who sank to ris<> no more."

In an old diary of

colonial times, kept by the Rev. Christopher Hozen, who was the pastor

of a small settlement of whites and Indians in Pennsylvania, there is an

account of a novel race, suggestive of running the gauntlet, gotten up

by the white settlers. In the spring of 1763 there were frequent

quarrels between the Indians and white people, which culminated

apparently in the murder of a white man named Murdock, with his wife and

child. Upon the wall of the cabin of Ninpo, an Indian, was found the

rude drawing of an arrow in blood, and at once suspicion rested upon him

as the perpetrator of the murderous act. The pastor of the small

community believed firmly in the innocence of his dusky friend, who was

not a Christian, but a shrewd, industrious and affectionate red man.

Sheinah, the Indian's wife, was an especial favorite of Patience, the

wife of the good missionary, who taught the dusky mother domestic

duties, and trained her in the use of the English language. Concerning

Ninpo, the pastor writes: " The young man I believe to be as innocent as

my own little child of this dreadful deed. He is too shrewd a fellow,

and the last person likely to sign his name to such a work of blood. I

do not think either that my townspeople really believe him guilty. But

they thirst for vengeance and must have a victim." Mr. Hozen managed to

put the time of trial off from month to month, while the poor man was

closely guarded in the fort.

The prisoner was almost

forgotten through pressure of colonial affairs, until the arrival of

Judge Poindexter, a coarse, burly man, with a rough voice, who hated the

Indians with intense hatred. He would have hanged Ninpo without a trial,

as he did not believe in giving justice to the red skins. As the

missionary remonstrated with him in relation to the Indian with his wife

and child, the surly minister of justice replied, in a loud tone of

voice, "Better hang her and the young cub. Stamp out a nest of snakes is

my way. He is not entitled to a trial, as you know very well, pastor.

He's a red skin. He has been kept there on our expense long enough. I

mean to have him out and put out. of the way next week." When Mr. Hozen

said, "You do not believe that he murdered Mr. Murdock?" The judge

replied, " No, I don't say that I do, but he's none too good to do it.

He's a worthless red devil, and I hold that the sooner we put an end to

him, and all of his color, the better." One of the friends of the

missionary, Seth Jarrett, knew how to manage this strange dispenser of

justice, and he suggested that they might have some fun at the expense

of Ninpo. The young men of the village were going to have some

hurdle-races and jumping matches, and Seth proposed to the judge that

the Indian be given a chance for his life, that he be allowed to run in

the races, and if he should lose one he should be hung, but if he won

all, he should be granted his liberty. The proposal pleased Judge

Poindexter, who knew that it would suit the rough tastes of the

villagers. The day of sport came round, and upon the field prepared for

the contests were groups of white men and women, and one solitary

Indian, namely the man who was to run for his life. The contest was

hardly a fair one, as the prisoner's joints were stiffened with three

month's confinement in prison. In the standing jump feat, an English

youth, named George Notting, defeated the Indian by three inches, and

the judge raised his rifle, when Seth interposed, remarking that he had

a chance in the race. In the dispute which ensued, some of the villagers

wishing to give him another chance for his life, and others willing to

prolong the sport, the decision was given in favor of Ninpo. Three men

stood abreast in a hundred yards race—Ninpo, John Gabberly and Abraham

Cutting. The judge, supported by a group of men, stood with his rifle

ready to shoot the Indian as lie ran. The runners started, Cutting ahead

and Ninpo close behind. Slowly the Indian gained, and then passed

Cutting, and as the people became excited, the whizz of a bullet sped

close to the ear of Ninpo from Poindexter's rifle. With a bound the

Indian rushed to the goal, and turning swiftly struck the judge heavily

in the stomach with his head, causing the fat man to roll over on the

grass amid the laughter of the spectators. It was the work of a moment

for Ninpo to reach the wood, where unseen stood the missionary's wife

with a horse, upon which he sprang and vanished from the presence of his

persecutor. Sheinah and her child, with the shrewd and nimble Ninpo,

found a home and safety in the western forests among their friends. A

year afterward the murderer of Murdock was discovered to be a white man

from another settlement. The bloody arrow upon the wall of the cabin was

the name of Ninpo, signifying Red Arrow. The red man's ideas of the

white man's laws and religion could not be elevated by hfe treatment,

and some of these have been transmitted to posterity.

The western Indians

enforced the custom of running the gauntlet as well as the tribes of the

east. The Blackfeet were accustomed to resort to it for sport, finding

pleasure in the attempts of their prisoners to reach a place of safety.

One of the most striking instances which happened among the Black-feet

was the thrilling experience of John Colter, a trapper, who had been a

member of the Lewis and Clarke expedition. Breaking loose from the

expedition at the headwaters of the Missouri, in the country inhabited

by the Gros Ventre, Crow and Blackfoot Indians, he began the lonely work

of a trapper with all the hardihood of this daring class of men. Meeting

another trapper named Potts, a partnership was formed, and along the

creeks and rivers they paddled, setting their beaver traps at the fall

of night and securing them before daybreak. Hiding in the daytime and

toiling during the night, they managed to elude the craftiness of the

Blackfeet. These men were well versed in prairie craft and Indian

customs; yet they were leading a dangerous kind of life for the sake of

the peltries they could obtain. As they were paddling softly at daybreak

in their canoe on a branch of the Missouri called Jefferson Fork, Colter

heard the trampling of feet, and instantly gave the alarm of Indians ;

but Potts assured him that it was a herd of buffalo, and they continued

their journey. The banks of the river were high and precipitous, and

although apprehensive of danger, there was apparent safety. Suddenly, as

they were stealing cautiously along the river, they were aroused with

hideous yells and war-whoops from both sides of the river. They were

entreated to come on shore, and as they complied, Colter stepped out of

the canoe, and Potts, when about to follow, was disarmed. Colter

snatched the gun from the hands of the Indian who had taken it and gave

it to Potts, who now distrusted the Blackfeet and determined to run the

chance of saving himself in his canoe. Pushing it from the shore, he had

not gone far when he called to his companion that he was wounded. Colter

entreated him to come on shore and trust to the Indians, as the only

chance of safety ; but he would not follow the instructions of his

friend. Determined to pay the Indians for their craftiness, he levelled

his gun and shot one of the Blackfeet dead. In a moment his body was

pierced with many arrows. Colter was led away to the camp of the

Blackfeet, about six miles distant, where the warriors deliberated as to

the treatment of their captive. The poor man, having a slight knowledge

of the language, listened intently to the schemes proposed which would

give them the greatest amusement. Some of the natives were anxious to

have him set as a mark 011 the prairie, at which they could test their

skill in shooting. One of the chiefs, seizing the captive by the

shoulder, asked him if he could run, and with the keen scent of an old

trapper he knew at once the purport of the question, that he would have

a chance of running for his life. Although noted among the trappers as a

good runner, he felt that his life now depended upon his skill, and he

informed the chief that he was a bad runner. Stripped naked, he was led

out on the prairie about four hundred yards, and at the sound of the

war-whoop the savages bounded after him at full speed.

Hew over the prairie

with the speed which gives fear to man, and although the prairie was

thickly studded with the prickly-pear cactus, which injured his feet, he

left his pursuers far behind. It was six miles to the Jefferson Fork,

and toward the river lie ran with might and main. Half-way across the

plain the swiftest runners were scattered, and Colter, looking round for

a moment, saw a single warrior about one hundred yards behind him, armed

with a spear. Through the excessive exertion the blood gushed from the

mouth and nostrils of Colter and streamed down his breast; still he ran

on. When within a mile of the river the sound of approaching footsteps

was distinctly heard, and the captive saw behind him, not more than

twenty yards, his pursuer armed with the spear. Suddenly turning round

and throwing up his

FLATHEAD MODEL CANOE.

arms lie faced the

savage, who became disconcerted through this act and the bloody

appearance of Colter. Stopping to hurl the spear, he fell forward

through exhaustion, the spear stuck in the ground and the shaft broke in

his hand. Colter rushed forward, seized the pointed part and pinned the

warrior to the ground. Continuing his flight toward the river, he

improved the delay caused by the Indians, who found their companion dead

and, with horrid yells, waited for the rest of the warriors to arrive.

Fainting and exhausted, Colter succeeded in gaining the fringe of

Cottonwood trees which skirted the river, through which he ran and

plunged into the stream. He swam to an island, against the upper end of

which a mass of driftwood had lodged, forming a natural raft, under

which he dived several times until, among the floating trunks of trees,

he found a place covered over with branches and bushes several feet

above the water," which secured for him a snug place of refuge.

Scarcely had he found

this temporary retreat than his pursuers arrived at the river, yelling

wildly, and madly rushing into the water swam toward the raft, which

they examined carefully and long. The poor man, suffering intensely,

could see the Blackfeet searching for him as he watched through the

chinks of the raft. The terrible thought that they were going to set the

raft on fire came to his mind, and increased his torture. All through

the day his pursuers searched, and not until night fell and no longer

was heard the sounds of the Indians did Colter leave his place of

safety. When silence reigned he dived again and came up beyond the raft,

and in the darkness swam quietly down the river for a considerable

distance. He landed upon the opposite bank and continued his flight

during the night, anxious to get beyond the reach of the Blackfeet, and

as far as possible from their country. Naked, without food or clothing,

with injured feet and exhausted strength, there still lay before him

several days' journey before he could reach a trading-post of the

Missouri, on a branch of the Yellowstone River. With heroic endeavor he

pursued his course over the prairies, his body smarting with the heat of

the sun by day and chilled with the dews of night, without a companion

to sustain or the means of securing game to support, living on roots or

berries, which he found by the way, until, after enduring many hardships

and overcoming all difficulties, he arrived at the trading-post, and

found shelter, sustenance and friends. Colter lived to relate his

discovery of the wonders of the famous Yellowstone Park and, like many

of the trappers of the west, spent his years with the Indians, and

passed away from earth " unwept, unhonored and unsung."

INDIAN CAIRNS.

Tablets of adamant!

Books of stone! Is it possible that savage man could make enduring

records upon materials so hard, or that facts and fancies belonged to

uncultured races of so great importance as to cause the bards of the

wigwams and lodges to write in characters indelible the story of bygone

years. A merry company was seated around the blazing lodge fire in the

home of Calf-Shirt as we entered, listening tostorios of valor told by

the aged warriors. Old .Medicine-Sun was finishing a story which we had

often heard, and after giving our quota of praise to our old friend for

his loyalty and courage, we said to the principal speaker at the lodge

fire, " Tell us the story of the writing stone." The question remained

unanswered, as some of the members of the company placed their hands

upon their mouths. Unable to gain the object of our visit, we determined

to be more discreet, and glean more carefully in other lodges the

secrets of the old days. A few uneventful days passed by, when,

sitting-alone by a favorite mound on the prairie, we were aroused from

our meditations by the voice of Peta. He was accompanied by a friend we

had known in earlier years. Alighting from their horses they took out

their pipes and began to smoke. The conversation turned upon the

pictured rocks of the Missouri, which my friend said wei;e wonderful. "

Many years ago," said he, " more than any of us can tell, the spirits

held a secret meeting relating to matters affecting the welfare of the

tribes. One of their number was delegated to make known the message of

the assembly of the spirits. Scattered far and wide were the tribes over

the Canadian North-West and the land of the Big Knives, but distance was

as nothing to a god. The wise men of the tribes would, however, die, and

there might be a time when the story of the meeting of the gods would be

forgotten, and darkness would then settle upon the red mem A more

enduring record must be left to guide the children of the wilderness,

such a record as unfaithful hands could not destroy, so, far aloft upon

the rocks of the Missouri, beyond the reach of mortals, the wisest of

the gods wrote out the divine message to all the tribes. I have gone

there and gazed upon that stone book, but could not understand it. Only

a few of the wisest men, one or two in each tribe, can interpret the

sayings of this wonderful record. They treasure its truths-carefully, as

they must not be told to unwilling or immoral ears. Whenever a wise man

has received the secret of this tablet of stone he becomes grave, and

rises quickly in the estimation of his tribe through the wisdom of his

counsels."

Peta finished his tale,

and his friend acquiesced in its truthfulness by an interjection of

frequent occurrence among the natives. The silence having been broken by

this exclamation of assent upon the part of our friend, he told us the

tale of his wanderings, how, when a youth among the Ojibways of Lake

Superior, he had travelled westward on an hunting expedition with a few

companions, but being suddenly cut off by a hostile band, he had fled

for safety to the bush, and became separated from his companions, whom

he never saw again. Several days he journeyed, living upon roots and

berries, but becoming exhausted, he determined to enter the first camp

of Indians he could find. As he wandered along the banks of one of the

rivers, he came upon an Indian trail, which he followed until he reached

a camp of Western Indians, who treated him kindly, and with whom he

remained until he found a home among the Blackfeet, near the Rocky

Mountains. Said he, " I remember when I was a boy, the old men of the

tribe telling me the story of the stone book on the great lake." We

parted, musing upon the fears and fancies of the red men. Gleams of

fancy shot across our path, as we wandered toward the western hills,

fragments of song and story, to which we had listened in the early days

among the lodges, and as in a vision we saw again the writing stones of

the South, which stand upon the prairie. Strange stories have the red

men told of these stones. The wonderful writing is there, the record of

the gods, and woe to that man who goes near them, unable to interpret

the strange words. Never again shall horse and rider return to dwell in

the land of the living. Young men and middle-aged men have gone there,

through idle curiosity, but never has one returned to tell the secret he

had discovered, or to relate his story of a visit to the land of

mystery. Wonderful story! It is a land of mystery ! Man of the earth,

mortal, not conversant with the things of the spiritual world, unable to

penetrate the shadows which hide us from the invisible, beware of

treading the soil of the gods, for it is an enchanted land, and if thou

utterest an impure word, or conceivest a carnal thought, thou shalt

inevitably die.

Riding carelessly over

the prairie with a young man who had lately arrived from the Old World,

my companion called my attention to a circle of stones. "That is a

mark," said he, "placed there to commemorate a great battle that was

fought between different tribes of Indians." Oftentimes had 1 seen these

circles on the prairie, and knowing the cause of their construction, I

was amused at this display of apparent wisdom. These circles are to be

found on our western prairies. As the Indians travelled on their hunting

expeditions, they placed stones around the edges of the lodges when they

camped, to prevent the wind from overturning them, and to keep them

warm. This is shown by the outer circle of stones. In the centre of the

lodge the fire was made, and to keep the fire from spreading and to

adapt it for cooking purposes, a small circle of stones was placed which

confined the fire. When the camp was moved the circle of stones was

left, and that which we saw was one of these circles. In the bush

fringing the rivers of the west stone circles, deeply imbedded in the

soil, are found, linking the past with the present. North-east of the

cemeteries of the town of Macleod, there are several cairns erected by

the Indians. I counted seven cairns of stone, one alone remaining

perfect, the others being deeply imbedded in the soil, and almost level

with the •surface of the prairie. The Indians have not been able to give

me any exact dates relating to the erection of the cairns, but native

tradition asserts that Southern Alberta was the home of the Snake, Nez

Perce, Crow, Flathead and Pend Oreille Indian tribes. The Cree and

Stoney Indians were the first of the tribes to obtain guns and

ammunition from the traders, which gave them superiority over their

enemies. The tribes comprising the Blackfoot Confederacy were living in

the north, and through contact with the white men they, too, become

possessors of firearms, and marching southward drove the Crow and Pend

Oreille tribes across the border. The Snake, Nez Perce and Flathead

tribes were driven across the mountains; and then directing their

attention to the Stoney and Cree tribes, tlicy extended their domain by

compelling them to retreat northward, until the district of Southern

Alberta, inhabited by the bullalo, became the undisputed territory of

the Blood, Piegan and Black-foot tribes. Several great battles were

fought, and these cairns were placed there to commemorate these events,

and probably to mark the spot where some of their greatest warriors

died. When a great chief or warrior died a lodge was placed over him,

and when this was thrown down by the wind, the body of the deceased was

laid upon the ground, and a cairn of stones erected over it. There is a

cairn called by the Indians the "Gamblers' Cairn," near the store of I.

G. Baker, in the town of Macleod. Several years ago a Piegan camp of

Indians located on this spot was attacked with small-pox, and the

disease proved so fatal that fifty dead lodges were left standing. Among

those who died was Aikfitce; i.e., the Gambler, head chief of the Piegan

tribe. His people placed a lodge over him, and when that had been blown

down by the western winds, he was reverently laid upon the ground, and

the cairn of stones erected. The original cairn was three or four feet

in diameter, with rows of stones between forty and fifty feet each in

length, leading to the cairn. Only one row of stones remains, and the

cairn is worn nearly level with the street. This simple monument is of

little interest to the passing stranger; but the Indian riding past will

turn to his comrade and quietly say, "Aikfttce."

These stone monuments

are to be found in widely scattered districts of the North-West, telling

their own simple story of other days. There are several rows of stones

several miles in length on the northern side of Belly River, near the

Blood Indian Reserve, and within three miles of the Slide Out Flat,

which can be seen when the prairie is burned. The Indians are unable to

give any account of their history. A line of boulders may still be seen

stretching from St. Mary's River northward for more than one hundred

miles. In some places they are quite close together, and at intervals

are separated by several miles. Some of them have been worn smooth by

the action of the weather, and by the buffalo using them as

rubbing-posts.

Indeed, you may see

some of them lying in hollow spots on the prairie, the soil having been

loosened by the tramping of the buffalo, and then blown away by the

wind.

Upon the summit of a

limestone hill on Moose Mountain, Assiniboia, there is a group of

cairns. The central cairn is composed of loose stones, and measures

about thirty feet in diameter and four feet high. This is surrounded by

a heart-shaped figure of stones, having its apex toward the east, and

from this radiate six rows of stones, each terminating in a small cairn.

Four of these radiating lines nearly correspond with the points of the

compass, and each of the lines of different lengths terminate in a

smaller cairn. The Indians know nothing of the origin of these lines and

cairns, but state that they were made by the spirit of the winds. In the

Lake of the Woods region there are numerous boulders grooved, polished

and marked by glacial action, and in the vicinity of Milk River are

boulders of various shapes and sizes. Within a few miles of Toronto, in

the Township of Vaughan, there was found a few years ago a flattened

oval granite cobble, resembling in shape and size a shoemaker's

lap-stone, having cut upon one side the date, "1641." This has been

called the "Jesuit's stone." In the spring of 1641, Brebeuf and

Chaumonot, Jesuit missionaries, left the country of the Neutrals for

their home among the Hurons, and were compelled to remain at the Indian

village of Teotongniaton, or St. Williams, where they were entertained

by a woman, probably belonging to the Aondironnons, a clan of the

Neutrals, for nearly a month. Dean Harris, of St. Catharines, who has

investigated the matter, thinks that probably during this journey the

missionaries commemorated the event by cutting the date in this stone.

Although not belonging

specially to the natives of the country, nor to Indian lore, yet as it

relates to the land of the red men, and is of interest to some of my

readers, I cannot help referring to the amethyst mines which I lately

visited. Accompanied by a few friends I had the pleasure of exploring

the mines where the beautiful amethysts are found, which are located

about fifteen miles east of Port Arthur and within two miles of the bay.

Some fascinating stories have-been told of the wealth of the mines, the

abundance of amethysts and the size of single amethysts, one of them

reputed to have been nearly one hundred pounds in weight, which sold for

fifteen hundred dollars. Whether the narrators drew upon their

imagination or not in telling these stories I cannot say, yet the deep

excavations reveal great labor which must have repaid the workers.

Numerous holes in the ground, from twenty to thirty feet in depth, and

from ten to twelve feet wide, were partially filled with debris, rich in

tiny amethysts of purple and brown, and the sides of the rocky caverns

glistened with thousands of beautiful specimens. Those found in the

rocks were, however, of little value, as they were destroyed in

blasting, but there were layers of clay wherein the single amethysts

were found in great profusion. Some years ago the mines were abandoned,

apparently on account of the heavy labor and the glutting of the market.

Beautiful stones of various colors are still found in abundance at Isle

Royale and along the shores of Lake Superior, which are sent to Germany

and made into ornaments. The traveller is enraptured when he beholds

their beauty and prizes them as. treasures of land and sea.

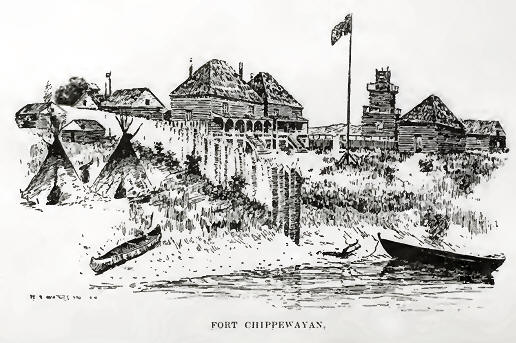

THE MOUNTED POLICE.

The southern portion of

the North-West Territories in the old buffalo days witnessed many an

exciting scene when the whiskey traders visited the Indian camps to

trade their goods, for the hides of the buffalo. The trade in buffalo

robes assumed such proportions that several traders from the United

States, were induced to enter the country of the Blackfeet to carry on

their trade. Some of these traders were not anxious to give or sell

whiskey to the natives, but they found others more successful in dealing

with them through the gift and sale of liquor that they felt compelled

to imitate their example. In trading with the red men the temptation

proved too strong to evade the liking for liquor shown by the men of the

western lodges.

and accordingly whiskey

of the worst kind was introduced, and some terrible scenes followed.

Many of the Indians drank the liquor until they died, and murders were

frequent. Fifty thousand robes, worth two hundred and fifty thousand

dollars, constituted the annual trade, and much of the proceeds, the

greater part the missionaries said, was spent in whiskey. The natives

sold their horses to the traders, crime increased, the native population

decreased, and the Blackfeet and Crees, beholding the fearful

consequences of the traffic, became anxious for its suppression. The

missionaries, by interviews and letters, sought the aid of the

Government, and at a meeting called George McDougall and Chief Factor

Christie, of the Hudson's Bay Company, a petition was drawn up to be

sent to the Dominion authorities requesting measures to be adopted for

the overthrow of the liquor trade among the Indians, and the maintenance

of law and order, suggesting that a military force be sent to the

country for that purpose. In 1871 Mr. Christie brought this matter

before Governor Archibald, and Chief Sweet Grass, head chief of the

Crees, in his message sent to the Governor at the same time, said, among

other things, "We want you to stop the Americans from coming to trade on

our lands and giving fire-water, ammunition and arms to our enemies, the

Blackfeet." The Dominion authorities issued a proclamation prohibiting

the traffic in spirituous liquors to Indians and others, and the use of

strychnine in the destruction of animal lift but the evils of the liquor

traffic still existed. In 1873 the Dominion Parliament passed an Act to

establish a military force in the North-West. This force, known as the

North-West Mounted Police, comprised three hundred men with the

proportionate complement of officers. In September, 1873, three

divisions of the force were organized at the Stone Fort, ne^ar Winnipeg,

and proceeded to Dufferin to await reinforcements from Montreal and

Toronto. Upon the arrival of the other three divisions from the east,

the preparations for the trip across the prairies were made, and on July

8th they left Dufferin on the famous march of 1874, under the command of

Eaeutenant-Colonel French. About the middle of September, the main

column, after many hardships, reached the Old Man's River, near the

present site of Macleod. A, B, C and F divisions being left there under

the Assistant-Commissioner, Lieutenant-Colonel Macleod proceeded at once

to erect log buildings as a police fort, which was named Fort Macleod. A

dozen men, under Colonel Jarvis, parted from the main column at Roche

Percee for Edmonton, where they arrived on the .second day of November.

The main column, under Colonel French, crossed the plains northward to

Fort Pelly by way of Qu'Appelle, but finding their intended headquarters

not ready returned to Dufferin. In four months the main column had

travelled one thousand, nine hundred and fifty-nine miles, besides the

distance covered by detachments on special service. Colonel Macleod

succeeded Colonel French as commissioner, and under his efficient

administration law and order were established in the country, the

whiskey traffic among the Indians wholly suppressed and life made

secure. I have listened to the genial commissioner as he related his

account of the march across the prairies, the vast herds of buffalo

seen, and adventures of great interest. The force consisted of six

divisions, named A, B, C, D, E, F. Fort Macleod was built in the form of

a square upon an island in the Old Man's River, the buildings consisting

of cotton-wood logs, filled in with mud, and subsequently with lime. It

was a frail-looking structure for defence in the country of the

Blackfeet, but the brave-hearted men trusted to their courage and honest

dealing with the Indians to maintain order more than to works of defence.

Fort Walsh was established in 1874 by Major Walsh. Considerable feeling

in the east and west wras manifested when it became known that a

military force was being organized for the Territories. Old soldiers of

the Imperial army settled in Canada, youthful aspirants to military

honors, college graduates and the sons of gentlemen of wealth and

political influence anxious to hunt the buffalo and take some scalps,

and worthless adventurers sought admission to the ranks. It was reported

that the whiskey traders were building fortifications to oppose the

police and many of the people were apprehensive of danger but the

whiskey traders were just as anxious as the friends of the police, for

they were ever on the alert, in expectation of the coming of the force,

assured that it meant the destruction of their business and, if caught,

the confiscation of their property.

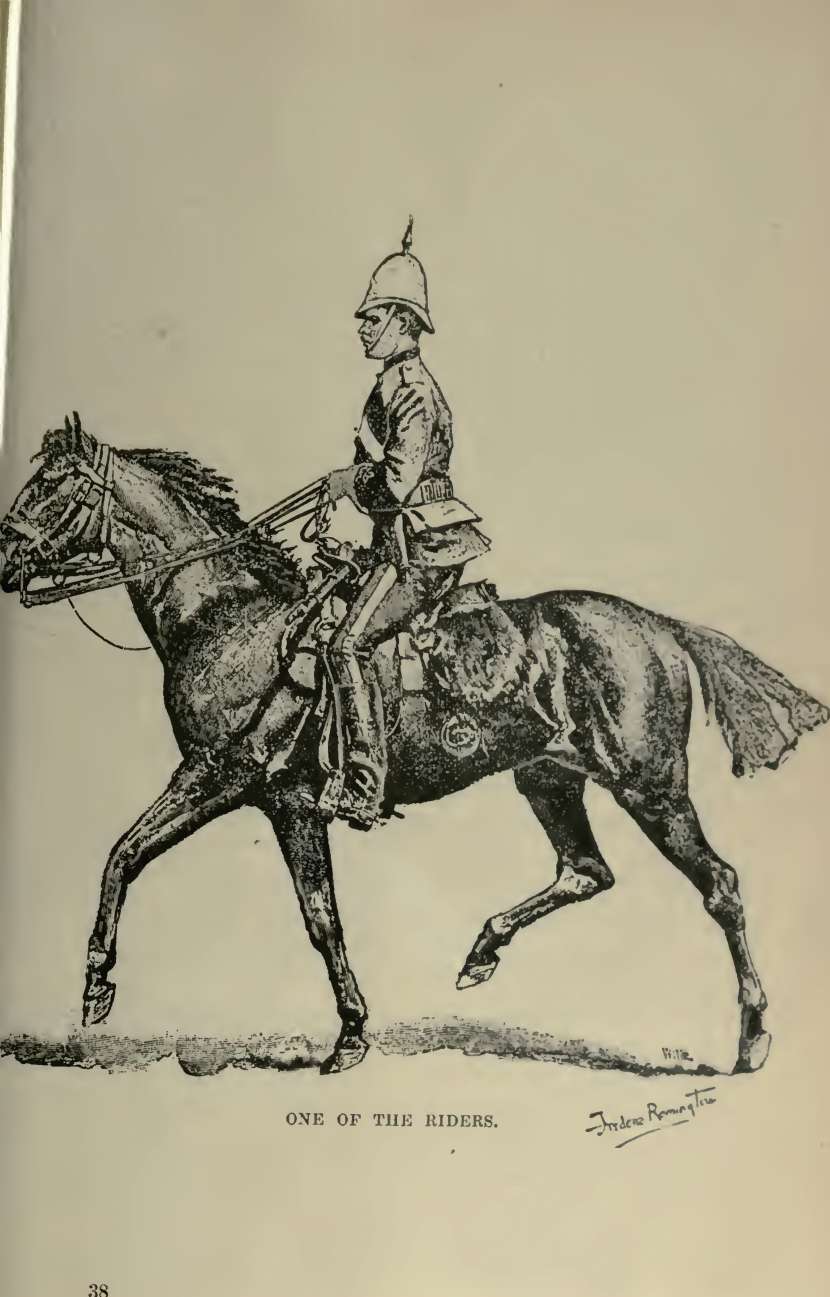

The force is graded as

commissioner, assistant-commissioner,, superintendent, inspector and

constable. One half of the force was armed with Winchester carbines and

Adams revolvers,, and the other half with Snider carbines and the same

revolver. Non-commissioned officers carried swords. The uniform was

scarlet tunic and serge, faced with yellow, black breeches with wide

yellow stripes and top boots. In summer white helmets and gauntlets were

worn, and in winter short buffalo coats, fur caps, mitts and moccasins.

The routine duties at the police forts were : Stables three times a day,

one hour of artillery and another of riding drill in the morning, and

one hour of riding drill in the afternoon. Men were told off as stable

orderlies,, regimental fatigue and room orderlies. Such a small force to

maintain peace in a country as large as all our Eastern Provinces

combined, inhabited by more than twenty thousand Indians-arid

half-breeds and numerous lawless persons, had no small task before them,

but their presence established order, and peaceful relations among all

classes were speedily made.

Shortly after the

police had stationed themselves at Fort Macleod some of the Blackfeet

paid a visit to the fort and were kindly treated by Colonel Macleod,

whom they named " Stamiksotokan," meaning Bull's Head, significant of

wise administration and military prowess. The genial commissioner

treated them kindly and with dignity. He invited them to inspect the

cannon, and then pointing to a tree more than a mile distant, told them

to look at it. Suddenly were they surprised as they saw the thick branch

of the tree carried away by the cannon ball, and the boom and smoke

startled them, leaving an indelible impression on their minds of the

strength and wisdom of the men who had arrived to govern the country.

From the beginning the riders of the plains gained the respect of the

natives, and ever since that period they have retained the confidence

imposed in them. It could not but happen that hostile relations would

exist at times, as the men of the scarlet tunic enforced justice, and

sought out and punished the criminals in the camps. The feuds among the

native tribes called for the interference of the police, and they were

able by their tact, energy and courage to prevent wars between the

tribes.

An incident

characteristic of this period happened at Fort Walsh in June, 1877. A

Saulteaux chief, named Little Child, came to Fort Walsh, and reported

that his people, numbering about fifty souls, were camped with a large

party of Assiniboines, and when they decided to move their camp an

Assiniboine, named Crow's Dance, formed a war lodge with two hundred of

his warriors, and then declared that the Saulteaux would not be allowed

to leave until lie gave them permission. Little Child protested, saying

that he would inform the White Mother's chief, and upon making

preparations to leave, the Assiniboines attacked the Saulteaux, killing

some of their dogs and threatening to work serious damage to the people.

When the bands separated, the Saulteaux chief went to Fort Walsh and

laid a complaint against Crow's Dance and his party. Major Walsh started

with a guide and fifteen men, at eleven o'clock in the forenoon, and

rode until three o'clock next morning, before they reached the camp of

the Assiniboines. Major Walsh, in Ium report of the affair, says, "The

camp was formed in the shape of a war camp, with a war lodge in the

centre. In the latter I expected to find Crow's Dance with his leaders.

Fearing they might offer resistance (Little Child said they certainly

would) I halted, and had the arms of my men inspected and pistols

loaded. Striking the camp so early, I thought I might take them by

surprise; so I moved west along a ravine about half a mile. This brought

us within three quarters of a mile of the camp. At a short trot we soon

entered the camp and surrounded the war lodge, and found Crow's Dance

and nineteen warriors in it. I had them immediately moved out of camp to

a small butte half a mile distant, and then arrested Blackfoot and

Bear's Down, and took them to the butte. It was now 5 a.m. I ordered

breakfast and sent the interpreter to inform the chiefs of the camp that

I would meet them in council in an hour. The camp was taken by surprise,

arrests made and prisoners taken to the butte, before a chief in the

camp knew anything about it. At the appointed time the following chiefs

assembled: Long Lodge, Shell King and Little Chief. I told them what I

had done, and that I intended to take the prisoners to the Fort and try

them by the law of the White Mother for the crime they had committed;

that they, as chiefs, should not have allowed such a crime to be

committed. They replied that they tried to stop it but could not. At 10

a.m. I left council and arrived at the Fort at 8 p.m., a distance of

fifty miles. If the Saulteaux, when attacked by the Assiniboines, had

returned the shot, there would in all probability have been a fearful

massacre." Lieutenant-Colonel Irvine, when reporting this affair to the

Government, wrote: "I cannot too highly write of Inspector Walsh's

prompt conduct in this matter, and it must be a matter of congratulation

to feel that fifteen of our men can ride into an enormous camp of

Indians, and take out of it as prisoners some of the head men. The

action of this detachment will have great effect on all the Indians

throughout the country." The Indians learned to trust the officers and

men of the force, who won their confidence, not through a false

sentimentality or through a laxity in discipline, but by enforcing

justice to red and white. During my residence at Fort Macleod a small

party of Blood Indians proceeded northward and stole some horses from

the camp of the Stoney Indians. Returning about midnight, as the horses

were being driven across the Old Man's River, an Indian woman residing

in the town aroused William Gladstone, the interpreter, who informed the

police, and in a few moments a mere handful of the red-coats were in hot

pursuit toward the Blood Indian Reserve. The night was dark, but they

gained rapidly upon the natives, and when they reached the band of

horses the red men had disappeared. A search through the camp during the

day resulted in the capture of an Indian named Jingling Bells. He was

taken to the Fort, and at the regular session of the court was tried by

jury and sentenced. Some of the natives vowed that he would never be

taken to Stoney Mountain Penitentiary, for Jingling Bells was a favorite

in the camp. When the time came for his removal he had to be <1 riven

across the prairie to Fort Walsh, about three hundred miles, and the

rumor from the camp of an attempt to release the prisoner having reached

the ears of the police, they had to resort to stratagem to get him

safely out of the country. One evening a small party of police left Fort

Macleod, but this caused 110 surprise, as it was a circumstance of

frequent occurrence. The party travelled until dark, and then camped for

the night. About midnight another party of police left the fort with the

prisoner and arrived at the police camp at sunrise, and Jingling Bells

was speedily transferred and hurried onward to prison without any delay.

The treaty at Blackfoot

Crossing in 1878, between the Government and the tribes inhabiting

Alberta, including the Black-feet, Bloods, Piegans, Sarcees, and Stoneys

was made successfully, and the presence of the police promoted peace,

allayed the fears and encouraged the hopes of the red men. Every year

the annual treaty payments made the transfer of a very large sum of

money in one-dollar bills a necessity, and this duty was faithfully

performed by the red-coats. During the payments their presence was

necessary on the Reserves, in the interests of the Government, the white

people and the Indians. When Sitting Bull and the hostile Sioux lied

from the United States and camped in the vicinity of Fort Walsh, the

energy, firmness and diplomacy of Major Crozier and his brother

officers, sustained by the police, prevented serious complications. I

well remember a disturbance at Blackfoot Crossing, when alxnit a dozen

men wrere stationed there under Captain Dickens, a son of Charles

Dickens, the novelist. One of the Black feet had committed some

depredation and the police attempted to arrest him, but the Indians

fired over their heads to intimidate them, and released the prisoner.

Trouble of a more serious nature was expected, and two policemen were

speedily despatched during the night to Fort Macleod for reinforcements.

Without a moment's delay Major Crozier, with a small detachment of

police, started for the sfoene of the disturbance. The distance was

about one hundred miles and by forced marches they arrived at Black-foot

Crossing at night. The sacks of oats were ranged inside the walls of the

frail log-buildings which served as police-quarters, and works of

defence were thrown up on the outside. When Crowfoot and his warriors

arose from their slumbers they were surprised to see the preparations

which had been made while they slept. The old chief held a conference

with Major Crozier, •and the brave soldier said he must have the

prisoner to take to Fort Macleod. When Crowfoot asked him what he would

do if he could not get him, he quietly said that then he must fight

until he got him. Crowfoot saw at once the determined attitude of his

friend, who now seemed his opponent, and he significantly turned to the

Major and said, "We will fight, then." With these words upon this lips

he retired, and the police made ready for action. It* needed the

utterance of a single word from Crowfoot and the entire camp would be

transformed into a war camp. The wise old chief understood men and

matters better than the Indians, and after weighing the circumstances

with the probable effects upon his people, he concluded that discretion

was the better part of valor, and in a short time he returned with the

prisoner, who was handed over to the minister of justice, who took him

to Fort Macleod, where he was tried and punished. I need not refer to

the heroism of the riders of the plains at Duck Lake, and indeed during

the whole of the rebellion. They were always ready to defend their

country and were ever foremost at the call of duty when danger stared

them in the face.

The police expected to

find in the haunts of the whiskey traders imposing fortifications and

fear was mutual, for the traders had heard of the advance of the men of

the scarlet tunic. The traders had their Spitzi Cavalry organized for

justice among themselves and defence against the Indians. There were

forts scattered over the country—the Old Bow Fort, about twelve miles

beyond Morley, in the valley of the Bow; a fort at Sheep Creek, a small

trading-post in the Porcupine Hills, between Mosquito Creek and the

Leavings of Willow Creek; Slide-Out, in one of the "bottoms" of the

Belly River; Stand-Oft', at the Junction of the Kootenay with the Belly

River, and Whoop-Up, at the Junction of the Belly and St. Mary's rivers.

The most formidable of these trading-posts was Whoop-Up. There was no

fighting, however, to be done, as the whiskey traders quietly gave up

their business and traded with the Indians without liquor. For some time

the police were satisfied with the erection of large forts, which were a

necessity during their first years in the country, and from these posts

they kept a sharp look-out on the administration of law in the country.

With the progress of settlement, consequent upon the extinction of the

buffalo, the peaceful attitude of the Indians and the establishment of

stock raising, it became necessary to locate small detachments in

different parts of the country. Some of these posts were named after the

officers, as Walsh and Macleod had been, and thus old Fort Kipp was

known as Fort Winder, and after the affair at Blackfoot Crossing, the

place of the parley was known amongst us as Fort Dickens. These names

have passed away never to return.

Long and lonely rides

over the prairie in the depth of winter were made by the members of the

force. Thrilling adventures could be told by some of the men of '74, but

they have made history without recording it. My first sad duty upon my

arrival in Macleod was

to bury a young policeman named Hooley, the son of an English Church

clergyman, who was drowned in Belly River when returning from a trip in

the discharge of his duties. I have seen the young man fresh from the

city, the child of luxury, start in the night when the thermometer was

thirty degrees below zero, to bear a despatch to a post thirty-five

miles distant; but he flinched not, for underneath the red coat there

beat a patriotic heart. Owe of these brave men went southward, bearing

an important message, but he never returned, and some of us thought lie

had taken advantage of the trust imposed in him by his officers and had

deserted. When the spring came, with its genial winds and sunshine, the

body of the faithful rider was found 011 the shore of the river where he

had disappeared, with no friendly aid to help in the hour of distress.

In the depth of winter another brave man, named Parker, started on his

errand of justice for the post on the St. Mary's River above the mouth

of Lee's Creek. It was an easy matter to lose the trail leading to the

police camp, and Parker missed it. He wandered around, suffering keenly

from the intense cold, and, becoming snow-blind, was unable to reach any

place of safety. For six days, without food, he travelled aimlessly 011

the prairie, eating snow to quench his thirst, and, removing the saddle

from his horse, he lay down 011 the bare spots made by the dumb animal

pawing the snow to obtain grass. With the instinct of a faithful friend

the horse would not leave him, although he turned it loose that it might

find its way to camp, but it stood near as if to encourage him. After

the days and nights of suspense he was found by the stage-driver of thv

mail waggon, and brought to the camp, where he was cared for until he

had partially recovered, when he was removed to the hospital in Macleod.

He was badly frozen and emaciated, but he finally regained his strength,

and his horse, Custer, became the hero of the fort.

Volumes could be

written of the heroic deeds and stirring adventures of the riders of the

plains. Officers and men were liberal in their gifts. A peculiar freak

of superstition or of self-interest was apparent in the fact that when a

long journey had to be undertaken, almost invariably they started on

Sunday. Sometimes there existed a partisan feeling among the citi/.eiLs

and police, which broke out at the public dance at Kamusi's Hotel, in

Macleod, where not a single white lady was present— as there were only

five within a radius of several hundred miles— and the dancers had to

find partners among the Indians and half-breed women. There was not a

dressmaker or milliner in the country, and the aspirants to the honors

of the ball-room would beg the white ladies to sell their dresses and

bonnets, and they were quite willing to pay big prices for them.

There were clever

schemers among the policemen, as might be expected where so many were

located, and one of these was a sergeant who had severed his connection

with the force and was engaged in farming. Driving into the fort with an

empty waggon he went to the storehouse and filled his waggon with sacks

of grain, and when about ready to start with his stolen goods he was

confronted by the officer in charge, who asked him what he was doing.

The wily ex-policeman replied that he wanted to exchange grain, as he

wished to get a new kind for seed for his farm. The officer summarily