|

THE BROOK TROUT

Salmo Fontinalis (Mitchell.)

The following description

of this fish—and I believe the latest—appears in the “Transactions of

the Nova Scotian Institute of Natural Science for 1866/’ and is due to

Dr. J. Bernard Gilpin, M.D.—

“The trout, as usually

seen in the lakes about Halifax, are in length from ten to eighteen

inches, and weight from half a pound to two pounds, though these

measurements are often exceeded or lessened. The outline of back,*

starting from a rather round and blunt nose, rises gradually to the

insertion of the dorsal fin, about two-thirds of the length of the head

from the nose ; it then gradually declines to the adipose fin, and about

a length and a half from that runs straight to form a strong base for

the tail. The breadth of the tail is about equal to that of the head.

Below, the outline runs nearly straight from the tail to the anal fin;

from thence it falls rapidly, to form a line more or less convex (as the

fish is in or out of season), and returns to the head. The

inter-maxillary very short, the maxillary long with the free end

sharp-pointed, the posterior end of the opercle is more angular than in

the S. Salar, the lower jaw shorter than upper when closed, appearing

longer when open. The eye large, about two diameters from tip of nose;

nostrils double, nearer the snout than the eye. Of the fins, the dorsal

has ten or eleven rays, not counting the rudimentary ones, in shape

irregularly rhomboid, but the free edge rounded or curved outward: the

adipose fin varies, some sickle-shaped with free end very long, others

having it very straight and short. The caudal fin gently curved rather

than cleft, but differing in individuals. Of the lower fins they all

have the first ray very thick and flat, and always faced white with a

black edge, the other rays more or less red. The head is blunt, and back

rounded when looked down upon. The teeth are upon the inter-maxillary

bone, maxillary bones, the palatine, and about nine on the tongue. There

are none so-called vomerine teeth, though now and then we find one tooth

behind the arch of the palate, where they are sometimes irregularly

bunched together. The colour varies; but through all the variations

there are forms of colour that, being always persistent, must be

regarded as typical. There are always vermilion spots on the sides;

there are always other spots, sometimes decided in outline, in others

diffused into dapples, but always present. The caudal and dorsal fins

are always spotted, and of the prevailing hue of the body. The lower

fins have always broad white edges, lined with black and coloured with

some modification of red. The chin and upper part of the belly are

always white. With these permanent markings, the body colour varies from

horn colour to greenish-grey, blue-grey, running into azure, black, and

black with warm red on the lower parts, dark green with lower parts

bright yellow; and, lastly, in the case of young fish, with vertical

bands of dusky black. The spots are very bright and distinct when in

high condition or spawning ; faint, diffused, and running into dapples

when in poor condition. In the former case all the hues are most vivid,

and heightened by profuse nacre.' In the other the spots are very pale

yellowish-white, running on the back into vermicular lines. The iris m

all is dark brown. I have seen the rose or red-coloured ones at all

times of the year. The young of the first year are greenish horn colour,

with brown vertical stripes and bright scarlet fins and tail, already

showing the typical marks and spots, and also the vermilion specs. Fin

rays D. 13, P. 13, Y. 8, A. 10 ; gill rays 12. Scales very small; the

dorsal has two rudimentary rays, ten or eleven long ones, varying in

different fish. Typical marks—axillary plate nearly obsolete, free end

of maxillary sharp, bars in young, vermilion specs, both young and adult

lower fins red with white and black edge.”

To the above description

I would add that the numerous yellow spots which prevail in every

specimen of S. Fontinalis vary from , bright golden to pale primrose,

that the colour of the specs inclines more to carmine than vermilion,

and that in bright, well-conditioned fish, the latter are surrounded by

circlets of pale and purest azure.

It will thus be seen that

the American brook trout is one of the most beautiful of fresh-water

fishes. Just taken from his element and laid on the moist moss by the

edge of the forest stream, a more captivating form can scarcely be

imagined. His sides appear as if studded with gems. The brilliant brown

eye and bronzy gill-covers reflect golden light; and the gradations of

the dark green back, with its fantastic labyrinthine markings, to the

soft yellow beneath, are marked by a central roseate tinge inclining to

lavender or pale mauve.

This species abounds

throughout the Northern States and British provinces, showing a great

variety as to form and colour (both external and of the flesh) according

to locality. In the swampy bog-hole the trout is black ; his flesh of a

pale yellowish-white, flabby and insipid. In low-lying forest lakes

margined by swamp, where from a rank soft bottom the water-lilies crop

up and almost conceal the surface near the shores, he is the same coarse

and spiritless fish. Worthless for the camp frying-pan, we leave him to

the tender mercies of the mink, the eel, and the leech. The bright, bold

trout of the large lakes, is a far different fish. His comparatively

small and well-shaped head, followed by an arched, thick shoulder, depth

of body, and brilliant colouring; the spirited dash with which he seizes

his prey, and, finally, the bright salmon-pink hue of his delicate

flesh, make him an object of attraction to both sportsman and epicure.

Such fish we find in the clearest water, where the shores of the lake

are fringed with granite boulders, with beaches of white sand, or

disintegrated granite, where the rush and the water-weeds are only seen

in little sheltered coves, where the face of the lake is dotted with

rocky, bush-covered islands, and where there are great, cool depths to

which he can retreat when sickened by the heat of the surface-water at

midsummer.

Though more a lacustrine

than a river fish, seldom attaining any size if confined to running

water between the sea and impassable falls, the American trout is found

to most perfection and in greatest number in lakes which communicate

with the sea, and allow him to indulge in his well ascertained

predilection for salt, or rather brackish tidal-water. A favourite spot

is the debouchure of a lake, where the narrowing water gradually

acquires velocity of current, and where the trout lie in skulls and give

the greatest sport to the fly-fisher.

In a recent notice of S.

Fontinalis from the pen of an observant sportsman and naturalist

appearing in “Land and Water,” this fish is surmised to be a char. Its

claim to be a member of the Salveline group is favoured by reference to

its similar habits in visiting the tidal portions of rivers on the part

of the char of Norway and Sweden, its similar deep red colouring on the

belly, and general resemblance. I am quite of “Ubique’s” opinion

touching this point, and think the common name of the American fish

should be char. Indeed, I find the New York char is one of the names it

already bears in- an American sporting work, though no comparison is

made. Besides its sea-going propensities, its preferring dark, still

waters, to gravelly shallow streams, and its resplendent colours when in

season, a most important point of resemblance to the char would seem to

be the minuteness of its scales.

The American trout spawns

in October and November in shallow water, and on gravel, sand, or mud,

according to the nature of the soil at the bottom of his domains.

In fishing for trout

through the ice in winter to add to our camp fare, I have taken them at

the “run in” to a large lake, the females full of spawn apparently ready

to drop at the end of January, and all in firm condition. This would

seem a curious delay of the spawning season : my Indian stated that

trout spawn in early spring as well as in the fall. They congregate at

the head of a lake in large numbers in winter, and readily take bait, a

piece of pork, or a part of their own white throats, let down on a hook

through the ice. In such localities they get a good livelihood by

feeding on the caddis-worms which crawl plentifully over the rocks under

water.

TROUT FISHING

Before the ice is fairly

off the lakes—and then a few days must be allowed for the ice-water to

run off— there is no use in attempting to use the fly for trout fishing

in rivers or runs, though eager disciples of Walton may succeed in

hauling out a few ill-fed, sickly looking fish from spots of open water

by diligently tempting with the worm at an earlier date. Indeed trout

may be taken with bait through the ice throughout the winter, but they

prove worthless in the eating. But after the warm rain storms of April

have performed their mission, and the soft west wind has coursed over

the surface of the water, then may the fisher proceed to the head of the

forest lake and cast his flies over the eddying pool where the brook

enters, and where the hungry trout, aroused to appetite, are congregated

to seek for food.

“Now, when the first foul

torrent of the brooks,

Swell’d with the vernal rains, is ebbed away,

And, whitening down their mossy-tinctur’d stream

Descends the billowy foam: now is the time,

While yet the dark-brown water aids the guile,

To tempt the trout.”

About the 10th of May in

Nova Scotia, when warm hazy weather occurs with westerly wind, the trout

in all the lakes and streams (an enumeration of which would be

impossible from their extraordinary frequency of occurrence in this

province) are in the best mood for taking the fly; and, moreover, full

of the energy of new found life, which appears in these climates to

influence such animals as have been dormant during the long winter,

equally with the suddenly outbursting vegetation. A few days later, and

the great annual feast of the trout commences—the feast of the May-fly.

Emerging from their cases all round the shores, rocky shallows, and

islands, the May-flies now cover the surface of the lakes in multitudes,

and are constantly sucked in by the greedy trout, which leave their

haunts, and disperse themselves over the lake in search of the alighting

insects. Although the fish thus gorge themselves, and, for some days

after the flies have disappeared, are quite apathetic, they derive much

benefit in flesh and flavour therefrom. The abundance of fish would

scarcely be credited till one sees the countless rises over the surface

of the water constantly recurring during the prevalence of the May-fly.

“It’s a steady boil of them,” says the ragged urchin with a long

“troutin’-pole,” as he calls his weapon, in one hand, and a huge cork at

the end of a string with a bunch of worms attached, in the other.

There is now no one more

likely place than another for a cast. Still sport may be had with the

artificial May-fly, especially in sheltered coves, where the fish resort

when a strong wind blows the insects off the open water. Some anglers of

the more patient type will take fish at this time on the lake by sitting

on rocks, and gently flipping out a very fine line with minute hooks, to

which the living May-fly is attached by means of a little adhesive fir

balsam, as far as they can on the surface of the water, where they float

till some passing fish rises and sucks in the bait. However the best

sport is to be obtained on the lakes a few days after the “May-fly

glut,” as it is termed, is over.

The May and stone flies

of America, which make their appearance about the same time, much

resemble the ephemeral representatives of their order found in the old

country. The May-fly of the New World is, however, different to the

green drake, being of a glossy black colour.

With the exception of

these two insects, we have no .representatives of natural flies in our

American fly-books. The scale is large and the style gaudy; and, if the

bunch of bright feathers, which sometimes falls over the head of Salmo

fontinalis, were so presented to the view of a shy English trout, I

question whether he would ever rise to the surface again. Artificial

flies are sold in most provincial towns in the Lower Provinces, and are

much sought for by the rising generation, who, however, often scorn the

store-rod, contenting themselves with a good pliable wattle cut in situ.

It is surprising to see the bunches of trout the settlers' “sonnies"

will bring home from some little lake, perhaps only known to themselves,

which they may have discovered back in the woods when hunting up the

cows; and the satisfaction with which the little ragged urchin will show

you barefoot the way to your fishing grounds, skipping over the sharp

granite rocks strewed in the path, and brushing through fir thickets

with the greatest resolution, all to become possessed of a bunch of your

flies and a small length of old gut.

The cast of flies best

adapted for general use for trout-fishing in Nova Scotia consists of the

red hackle or palmer, a bright bushy scarlet fly, with perhaps a bit of

gold twist or tinsel further to enhance its charms, a brown palmer, and

a yellow-bodied fly of wool with mallard wings. The latter wing on a

body of claret wool with gold tinsel is also excellent. Many other and

gaudier flies are made and sold to tempt the fish later on in the year :

they are quite fanciful, and resemble nothing in nature. I cannot

recommend the artificial minnow for use in this part of the world,

though trout will take them. They are always catching on submerged

rocks, and are very troublesome in many ways. The most successful minnow

I ever used was one made on the spot by an Indian who was with me after

moose—a common large trout-hook thickly bound round with white worsted,

a piece of tinfoil covering the under part, and a good bunch of

peacock’s herl inserted at the head, bound down along the back, and

secured at the end of the shank, leaving a little projection to

represent the tail. It was light as a feather, and could be thrown very

accurately anywhere—a great advantage when you find yourself back in the

woods and wish to pull a few trout for the camp frying-pan from out a

little pond overhung with bushes. The fish took it most greedily.

The common trout is to be

met with in every lake, or even pond, throughout the British Provinces.

One cannot walk far through the depths of a forest district before

hearing the gurgling of a rill of water amongst stones beneath the moss.

Following the stream, one soon comes on a sparkling forest brook

overhung by waving fern fronds, and little pools with a bottom of golden

gravel. The trout is sure to be here, and on your approach darts under

the shelter of the projecting roots of the mossy bank. A little further,

and a winding lane of still water skirted by graceful maples and

birches, leads to the open expanses of the lake, where the gloom of the

heavy woods is exchanged for the clear daylight. This is the “run in,”

in local phraseology, and here the lake trout resort as a favourite

station at all times of the year. A basket of two or three dozen of

these speckled beauties is your reward for having found your way to

these wild but enchanting spots.

Though, as has been

observed, the trout of America is more a lake than a river fish, yet the

gently running water at the foot of a lake just before the toss and

tumble of a rapid is reached is a favourite station for trout. Such

spots are excellent for fly-fishing ; I have frequently taken five dozen

fine fish in an hour, in the Liverpool, Tangier, and other noble rivers

in Nova Scotia, from rapid water, weighing from one to three pounds.

Towards midsummer the

fish begin to refuse fly or bait, retiring to deep pools under the shade

of high rocks, sickened apparently by the warmth of the lake water. As,

however, the woods, especially in the neighbourhood of water, are at

this season infested with mosquitoes and black flies, a day’s “outing”

by the lake or river side becomes anything but recreative, if not

unbearable. The twinge of the almost invisible sand-fly adds, too, to

our torments. In Nova Scotia the savage black-fly (Simulium molestum)

disappears at the end of June, though in New Brunswick the piscator will

find these wretches lively the whole summer. They attack everything of

life moving in. the woods, being dislodged from every branch shaken by a

passing object. No wonder the poor moose rush into the lakes, and so

bury themselves in the water that their ears and head are alone seen

above the surface. In Labrador the flies are yet worse, and travelling

in the interior becomes all but impracticable during the summer.

In August the trout

recover themselves under the cooling influence of the frosty atmosphere

which now prevails at night, and will again take the fly readily,

continuing to do so until quite late in the fall, and even in the

spawning season.

THE SEA TROUT

(Salmo Canadensis (Hamilton Smith).

Closely approximating to

the brook trout in shape and colouring—especially after having been some

time in fresh water—the above named species has been pronounced

distinct. They have so near a resemblance that until separated by the

careful comparison of Dr. Gilpin, I always believed them to be the same

fish, especially as the brook trout as aforesaid is known to frequent

tidal waters at the head of estuaries. The following description of the

sea trout is taken from Dr. Gilpin’s article on the Salmonidee before

alluded to, and is the result of examination of several fish taken from

fresh water, and in the harbour :—

“Of those from the

tide-way, length from twelve to fourteen inches; deepest breadth,

something more than one quarter from tip of nose'to insertion of tail.

The outline rounds up rather suddenly from a small and arched head to

insertion of dorsal; slopes quickly but gently to adipose fin; then runs

straight to insertion of caudal; tail gently curved rather than cleft;

lower line straight to anal, then falling rather rapidly to make a very

convex line for belly, and ending at the gills. The body deeper and more

compressed than in the brook trout. The dorsal is quadrangular; the free

edge convex ; the lower fins having the first rays in each thicker and

flatter than the brook trout. The adipose fin varies, some with very

long and arched free end, in others small and straight. The specimen

from the fresh water was very much longer and thinner, with head

•proportionally larger. The colour of those from the tide-way was more

or less dark greenish blue on back shading to ash blue and white below,

lips edged with dusky. They all had faint cream-coloured spots, both

above and below the lateral line. With one exception, they all had

vermilion specs, but some only on one side, others two or three. In all,

the head was greenish horn colour. The colour of the fins in pectoral,

ventral, and anal, varied from pale white, bluish-white, to pale orange,

with a dusky streak on different individuals. Dorsal dusky with faint

spots, and caudal with dusky tips—on some a little orange wash. The

lower fins had the first ray flat, and white edged with dusky. In the

specimen taken on September the 10th from the fresh water, the blue and

silver had disappeared, and dingy ash colour had spread down below the

lateral line; the greenish horn colour had spread itself over the whole

gills except the chin, which was white. The silvery reflections were all

gone, tlie cream-coloured dapples were much more decided in colour and

shape, and the vermilion specs very numerous. The caudal and all the

lower fins had an orange wash, the dorsal dusky yellow with black spots,

the lower fins retaining the white flat ray with a dusky edging, and the

caudal a few spots. The teeth of all were upon the inter-maxillary,

maxillaries, palatine, and the tongue; none on the vomer except now and

then one tooth behind the arch of palate. Fin rays, D. 13, P. 13, V. 8,

A. 10 ; gill rays 12. Axillary scale very small. Dorsal, with two

rudimentary rays, ten or eleven long ones, free edge convex; first ray

of lower fins flat, scales very small, but rather larger than those of

brook trout.’’

Dr. Gilpin sums up as

follows on the question of its identity with brook trout:—

“We must acknowledge it

exceedingly closely allied to Fontinalis—that it has the teeth, shape of

fins, axillary plate, tail, dapples, vermilion specs, spotted dorsal,

alike; that when it runs to fresh water it changes its colour, and, in

doing this, approximates to its red fin and dingy green with more

numerous vermilion specs, still more closely. Whilst, on the other hand,

we find it living apart from Fontinalis, pursuing its own laws,

attaining a greater size, and returning year after year to the sea. The

Fontinalis is often found unchanged under the same circumstances. The

former fish always preserves its more arched head, deeper and more

compressed body, and perhaps shorter fins. In giving it a specific name,

therefore, and using the appropriate one given by Colonel Hamilton

Smith—so far as I can discover the first de-scriber—I think I will be

borne out by all naturalists.”

The size attained by this

fish along the Atlantic coasts rarely exceeds five pounds : from one to

three pounds is the weight of the generality of specimens. The favourite

localities for sea trout are the numerous harbours with which the coasts

of the maritime provinces (of Nova Scotia in particular) are frequently

indented. First seen in the early spring, they affect these harbours

throughout the summer, luxuriating on the rich food afforded on the sand

flats, or amongst the kelp shoals. On the former localities the

sand-hopper (Talitrus) seems to be their principal food; and they pursue

the shoals of small fry which haunt the weeds, preying on the smelt (Osmerus)

on its way to the brooks, and on the caplin (Mallotus) in the harbours

of Newfoundland and Cape Breton. They will take an artificial fly either

in the harbour or in fresh water.

When hooked by the

fly-fisherman on their first entrance to the fresh water, they afford

sport second only to that of salmon-fishing. No more beautiful fish ever

reposed in an angler s basket. The gameness with which they prolong the

contest—often flinging themselves salmon-like from the water—the

flashing lights reflected from their sides as they struggle for life on

removal of the fly from their lips, their graceful form, and colouring

so exquisitely delicate—sides molten-silver with carmine spangles, and

back of light mackerel-green —and, lastly, the delicious flavour of

their flesh when brought to table, entitle the sea trout to a high

consideration and place amongst the game-fish of the provinces.

In some harbours the

trout remains all the summer months feeding on its favourite grounds,

but in general it returns to its native fresh water at distinctly marked

periods, and in large detachments. In the early spring, before the snow

water has left the rivers, a few may be taken at the head of the

tide—fresh fish from the salt water mixed with logies, or spent fish

that have passed the winter, after spawning in the lakes, under the ice.

The best run of fish occurs in June—the midsummer or strawberry run, as

it is locally called—the season being indicated by the ripening of the

wild strawberry. As with the salmon, there is a final ascent, probably

of male fish, late in the fall. The spawning fish remain under the ice

all winter in company with the salmon, returning to sea as spent fish

with the kelts when the rivers are swelled by freshets from the melting

snow.

SEA TROUT FISHING

A more delightful season

to the sportsman than “strawberry time” on the banks of some fine river

entering an Atlantic harbour and well known for its sea trout fishing,

can hardly be imagined. With rivers and woods refreshed by recent rains,

the former at a perfect state of water for fishing, and the river-side

paths through the forest redolent with the aroma of the summer flora,

and the delicious perfume of heated fir boughs, the angler’s camp is, or

should be, a sylvan abode of perfect bliss. Or even better — for then we

are free from the persistent attack of mosquito or black fly — is the

cabin of a comfortable yacht, in which we shift from harbour to harbour,

anchoring near .the mouth of the entering river. The flies and sea fog

are only drawbacks to the pleasant holiday of a trouting cruise along

shore. The former seldom venture from land (even on the forest lake they

leave the canoe or raft at a few yards’ distance from the shore) and, if

the west wind be propitious, the cold damp fog is driven away to the

north-east, following the coast line, several miles out to sea.

Nothing can exceed the

beauty of scenery in some of the Atlantic harbours of Nova Scotia; their

innumerable islands and heavily-wooded shores fringed with the golden

kelp, the wild undulating hills of maple rising in the background, the

patches of meadow, and the neat little white shanties of the fishermen’s

clearings, are the prettiest and most common details of such pictures,

w^hich never fade from the memory of the lover of nature. How easily are

recalled to remembrance the fresh clear summer mornings enjoyed on the

water; the fir woods of the western shores bathed in the morning

sunbeams, the perfect reflections of the islands and of the little

fishing schooners, the wreaths of blue smoke rising from their cabin

stoves, and rendered distinct by the dark fir woods behind, and the roar

of the distant rapids, where the river joins the harbour, borne in

cadence on the ear, mingled with the cheerful sounds of awakening life

from the clearings. The bald-healed eagles (H. leucocephalus) sail

majestically through the air, conspicuous when seen against the line of

woods by their snow-white necks and tails. The graceful little tern

(Sterna hirundo) is incessantly occupied, circling over the harbour,

shrilly screaming, and ever and anon dashing down upon the water to

clutch the small fry; whilst the common kingfisher, as abundant by the

sea-shore as in the interior, thinking

MUSQUODOBOIT HARBOUR.

all fish, salt or fresh

water, that come to his net, equally good, shoots over the harbour with

jerking flight, and uttering his wild rattling cry; now and then he

makes an impetuous downward dash, completely burying himself beneath the

surface in seizing his prey.

If there is a run of

trout, and we wish to fish the river, we go to the sea-pools, which the

fish enter with the rising tide, and where we may see their silvery

sides flashing as they gambol in the eddies under the apparently

delightful influence of the highly-aerated water of a large and rapid

stream, or as they rush at the dancing deceit which we agitate over the

surface of the pool. Here, in their first resting-place on their way up

the river, they will always take the fly most readily; and with good

tackle, a propitious day, and the by no means despicable aid of a smart

hand with the landing-net, the mossy bank soon glitters with a dozen or

two of these delicious fish.

Should they not be

running, or shy of rising in the fresh water from some of the many

unaccountable humours in which all game fish are apt to indulge, harbour

fishing is our resource, and we betake ourselves to the edge of the sand

flats where the fish, dispersed in all directions during high water, now

congregate and lie under the weeds which fringe the edge of the tide

channels. Half-tide is the best time, and the trout rush out from under

the kelp at any gaudy fly, temptingly thrown towards the edge, with a

wonderful dash, and may be commonly taken two at a time. The

trout-beaches in Musquodoboit Harbour, lying off Big Island, of which an

engraving is given, may be a pleasant remembrance to many who may read

these lines.

A deserted clearing, with

soft grassy banks positively reddened with wild strawberries, is a most

tempting spot for a picnic, and we go ashore with pots and pans to

bivouac on the sward. “ Boiled or fried, shall be the trout ? ” is the

question ; we try both. Perhaps the former is the best way of cooking

the delicate and salmon-flavoured sea trout (especially the larger

fish), but in camp we generally patronise a fry, and this is our mode of

proceeding. The fire must be bright and low, the logs burning without

smoke or steam; the frying-pan is laid on with several thick slices of

the best flavoured fat pork, and, when this is sufficiently melted and

the pan crackling hot, we put in the trout, split and cleaned, and lay

the slices of pork, now sufficiently bereft of their gravy, over them. A

little artistic manoeuvring, so as to lubricate the rapidly browning

sides of the fish, and 'they are turned so soon as the under surface

shows of a light chestnut hue. Just before taking off, add the seasoning

and a tablespoonful of Worcester. The tin plates are now held forth to

receive the spluttering morsels canted from the pan, and we fall back on

the couch of maple boughs to eat in the approved style of the ancients,

whilst the fresh midday breeze from the Atlantic modifies the heat, and

drives away to the shelter of the surrounding bushes the fisherman’s

most uncompromising foes—the mosr quitoes and black flies.

In Nova Scotia the best

localities for pursuing this attractive sport are the harbours to the

eastward of Halifax—Musquodoboit, Tangier, Ship, Beaver, Liscomb, and

Country harbours. In Cape Breton the beautiful Margarie is one of the

most noted streams for sea trout, and its clear water and picturesque

scenery, winding through intervale meadows dotted with groups of witch

elm, and backed by wooded hills over a thousand feet in height, entitle

it to pre-eminence amongst the rivers of the Gulf.

Prince Edward's Island

affords some good sea-trout fishing, and, further north, the streams of

the Bay of Chaleurs and of both shores of the St. Lawrence are so

thronged with this fish, in its season, near the head of the tide, as

seriously to impede the salmon fisher in his nobler pursuit, taking the

salmon fly with a pertinacity against which it is useless to contend;

nor is he free from their attacks until a cascade of sufficient

dimensions has intervened between the haunts of the two fish.

THE SALMON

(Salmo Salar.)

The Salmon of the

Atlantic coasts of America not having been as yet specifically separated

from the European fish, a scientific description is unnecessary, and we

pass on to note the habits of this noble game fish of our provincial

rivers.

From the once productive

rivers of the United States —with the exception of an occasional fish

taken in the Penobscot, or the Kennebec in Maine—the salmon has long

since been driven, the last recorded capture in the Hudson being in the

year 1840. Mr. Roosevelt, a well-known American sportsman and author,

states that “the rivers flowing into Lake Ontario abounded with them,

even until a recent period, but the persistent efforts at their

extinction have at last prevailed ; and, except a few stragglers, they

have ceased from out our waters.”

Cape Sable being, then,

the south-easternmost point in the salmon's range, we first find him

entering the rivers of the south coast of Nova Scotia very early in

March, long before the snow has left the woods; thus disproving an

assertion that he will not ascend a river till clear of snow water. At

this time he meets the spent fish, or kelts, returning from their dreary

residence under the ice in the lakes, and these gaunt, hungry fish may

be taken with most annoying frequency by the angler for the new comers.

As a broad rule, with,

however, some singular exceptions, the run of salmon now proceeds with

tolerably progressive regularity along the coast to the eastward and

northward, the bulk of the fish having ascended the Nova Scotian rivers

by the middle of June. The exceptions referred to occur in the case of a

large river on the eastern coast of Nova Scotia—the Saint Mary—and some

of the tributaries of the Bay of Fundy, in which there is a run of fish

in March, as on the south-eastern coast. This fact militates somewhat

against the theory of the salmon migrating in winter to warmer waters to

return in a body in early spring and ascend their native rivers,

entering them progressively.

In the Bay of Chaleurs

the season is somewhat more delayed ; the fish are not fairly in the

fresh water before the middle of June, which is also the time for their

ascending the rivers of Labrador.

At midsummer in Nova

Scotia, and in the middle of July higher up in the gulf, the grilse make

their appearance in fresh water in company with the sea trout. They are

locally termed jumpers, and well deserve the title from their liveliness

when hooked. With a light rod and fine tackle they afford excellent

sport, and take a small bright, yellowish fly with great boldness.

The American salmon

spawns very late in the fall, not before November, and for this purpose

affects the same localities as his European congener—shallow waters

running over beds of sand and gravel. The spawning grounds occur not

only in the rivers, but around the large parent lakes, at the entrance

of the little brooks that feed them from the forest, and where there are

generally deltas formed of sand, gravel, and disintegrated granite

washed down from the hills. The spent fish, as a general rule, though

some return with the last freshets of the year, remain all winter under

the ice (particularly if they have spawned in lakes far removed from the

sea), returning in the following spring, when numbers of them are taken

by the settlers fishing for trout with worm in pools where the runs

enter the lakes. They are then as worthless and slink as if they had but

just spawned. In May the young salmon, termed smolts, affect the

brackish water at the mouth of rivers, and fall a prey to juvenile

anglers in immense numbers—a practice most destructive to the fisheries,

as these little fish would return the same season as grilse of three or

four pounds weight. The salmon of the Nova Scotian rivers vary in weight

from seven to thirty pounds, the latter weight being seldom attained,

though a fair proportion of fish brought to market are over twenty

pounds. Those taken in the St. Mary are a larger description of fish

than the salmon of the southern coast. In the Bay of Chaleurs, in the

Restigouche, salmon of forty and fifty pounds are still taken; in former

years, sixty pounds and over was not an uncommon weight. The salmon of

the Labrador rivers are not remarkable for size: the average weight of

two hundred fish taken with the fly in the river St. John in July, 1863,

was ten pounds, the largest being twenty-three; and the largest salmon

ever taken by the rod on this coast weighed forty pounds.

The average weight of the

grilse taken in Nova Scotia and the Gulf appears to be four pounds. Fish

of seven or eight pounds which I have taken in American rivers are, to

my thinking, salmon of another years growth, and present an appreciable

difference of form to the slim and graceful grilt. In the latter - part

of November, the time when the salmon in the fresh water are in the act

of spawning, a run of fish occurs along the coast of Nova Scotia. They

are taken at sea by nets off the headlands, and are, as affirmed by the

fishermen, proceeding to the southward. Brought* to market, they are

found to be nearly all females, in prime condition, with the ova very

small and in an undeveloped state, similar to that contained in a fish

on its first entrance into fresh water. Where can these salmon be going

at the time when the rest of their species are busily engaged in

reproduction ? Another of the many mysteries attached to the natural

history of this noble fish ! In fresh running water the salmon takes the

artificial fly or minnow, whether from hunger or offence it does not

clearly appear; in salt water he is not unfrequently taken on the coast

of Nova Scotia by bait-fishing at some distance from shore, and in sixty

or seventy fathoms water. The caplin, smelt, and sand-eel, contribute to

his food.

Dr. Gilpin, of Nova

Scotia, speaking of many instances of marvellous captures of salmon,

tells the following authentic story; the occurrence happened in his own

time and neighbourhood—Annapolis :—

“Mr. Baillie, grandson of

the ‘Old Frontier Missionary' was fishing the General’s Bridge river up

stream for trout, standing above his knees in water, with an old negro

named Peter Prince at his elbow. In the very act of casting a trout fly

he saw, as is very usual for them, a large salmon lingering in a deep

hole a few yards from him. The sun favoured him, throwing his shadow

behind. To remain motionless, to pull out a spare hook and penknife, and

with a bit of his old hat and some of the grey old negro’s wool to make

a salmon fly then and there, he and the negro standing in the running

stream like statues, and presently to land a fine salmon, was the work

of but a few moments. This fly must have been the original of Norris’s

killing £ silver grey.’”

THE RIVERS OF NOVA SCOTIA

AND THE GULF.

Rivers and streams of

varying dimensions, but nearly all accessible to salmon, succeed each

other with wonderful frequency throughout the whole Atlantic Sea-board

of Nova Scotia. In former years, when they were all open to the ascent

of migratory fish, the amount of piscine wealth represented by them was

incalculable. The salmon literally swarmed along the coast. Their only

enemy was the spear of the native Indian; and the earlier annals of the

province show the prevalence of a custom with, regard to the hiring of

labourers similar to that once existing in some parts of England—a

stipulation that not more than a certain proportion of salmon should

enter into their diet. Now, the salmon having passed the ordeal of

bag-nets, with which the shores of the long harbours are studded, and

arrived in the fresh water, vainly loiters in the pool below the

monstrous wooden structure called a mill-dam, which effectively debars

his progress to his ancestors’ domains in the parent lakes, and before

long falls a prey to the spear or scoop-net of the miller. FronjL

wretchedly inefficient legislation the salmon of Nova Scotia is on the

verge of extinction, with the gaspereaux and other migratory fish, which

once rendered the immense extent of fresh water of .this country a

source of wealth to the province and of incalculable benefit to the poor

settler of the backwoods, whose barrels of pickled fish were his great

stand-by for winter consumption.

One of the noblest

streams of the Nova Scotian coast is the Liverpool river, in Queen’s

County, which connects with the largest sheet of fresh water in the

province, Lake Eossignol, whence streams and brooks innumerable extend

in all directions through the wild interior, nearly crossing to the Bay

of Fundy. All these once fruitful waters are now a barren waste. The

salmon and gaspereaux are debarred from ascent at the head of the tide,

where a series of utterly impracticable mill-dams oppose their progress

to their spawning-grounds. A pitiful half dozen barrels of salmon taken

at the' mouth is now shown against a former yearly take of two thousand.

A few miles to the

eastward we come to the Port Medway river, nearly as large as the

preceding, which, not being so completely closed against the salmon,

still affords good sport in the beginning of the season, in April and

May. This is the furthest river westwardly from the capital of the

province—Halifax—to which the attention of the fly-fisher is directed.

There are some excellent pools near the sea, and at its outlet from the

lakes, twenty miles above. The fish are large, and have been taken with

the fly in the latter part of March. The logs going down the stream are,

however, a great hindrance to fishing.

Proceeding to the

eastward, the next noticeable salmon river is the La Have, the scenery

on which is of the most picturesque description. There are some

excellent pools below the first falls. The run of fish is rather later

than at Port Medway, or at Gold River, which is further east. On the 4th

of May, when excellent sport was being obtained in these waters, I have

found no salmon running in the La Have. About the 10th of May appears to

be the beginning of its season.

We next come to Mahone

Bay, an expansive indentation of the coast, studded with islands, noted

for its charms of scenery, and likewise commendable to the visitor in

search of salmon-fishing. About six miles west of the little town of

Chester, which stands at its head, is the mouth of Gold River. Until

very recently this was the favourite resort of sportsmen on the western

shore. Its well-defined pools and easy stands for casting added to its

inducements; and a throng of fish ascended it from the middle of April

to the same time in May. The increase of sporting propensities amongst

the rising generation of the neighbouring villages proves of late years

a great drawback to the chances of the visitor. The pools are

continually occupied by clumsy and undiscerning loafers, who infest the

river to the detriment of sport, and do not scruple to come alongside

and literally throw across your line. Though dear old Isaac might not

possibly object to rival floats a yard apart, another salmon-fly

careering in the same pool is not to be endured, and of course spoils

sport. Still, however, without such interruptions, fair fishing may be

obtained here, and a dozen fish of ten to twenty pounds taken by a rod

on a good day. Excessive netting in the salt water is, however, fast

destroying all prospects of sport here as elsewhere.

There are two fair sized

salmon rivers entering the next harbour, Margaret’s Bay, which, being

the nearest to the capital of the province, are over-fished. With the

exception of a pretty little stream, called the Nine-mile River, which

is recovering itself under the protection of the Game and Fish

Preservation Society, these conclude the list of the western-shore

rivers of Nova Scotia.

The fishing along this

shore is quite easy of access by the mail-coach from Halifax, which

jolts somewhat roughly three times a week over the rocks and fir-pole

bridges of the shore-road through pretty scenery, frequently emerging

from the woods, and skirting the bright dancing waters of Margaret’s Bay

and Chester Basin. The woodland part of a journey in Nova Scotia is

dreary enough; the dense thickets of firs on either side being only

enlivened by an occasional clearing with its melancholy tenement and

crazy wooden out-buildings, and by the tall unbarked spruce-poles stuck

in a swamp or held up by piles of rocks at their base, supporting the

single wire along which messages are conveyed through the province

touching the latest prices afloat of mackerel, cod-fish, or salt, on the

magnetic system of Morse.

Indian guides to the

pools, who are adepts at camp-keeping, canoeing, and gaffing the fish

for you, as well as at doing a little stroke of business for themselves,

when opportunities occur, with the forbidden and murderous spear, reside

at the mouths of most of these rivers. Their usual charge, as for

hunting in the woods, is a dollar per diem.

The flies for the western

rivers of Nova Scotia are of a larger make than those used in New

Brunswick and Canada, owing to the turbidity of the water at the season

when the best fishing is to be obtained. They may be procured in several

stores in Halifax, where one Connell ties them in a superior style, and

will forward them to order anywhere in the provinces or in Canada. A

claret-bodied (pig’s wool or mohair) with a dark mixed wing is good for

the La Have. Green and grey are good colours for Gold River. With the

grey body silver tinsel should be used, and wood-duck introduced into

the wing. An olive body is also good. There is no feather that sets off

a wing better than wood-duck. It is in my estimation more tempting to

fish than the golden pheasant tippet feather. Its broad bars of rich

velvety black and purest white give a peculiarly attractive and soft

moth-like appearance to the wing.

The harbour of Halifax,

nearly twelve miles in length, has but one stream, and that of

inconsiderable dimensions, emptying into it. The little Sackville river

was, however, once a stream affording capital sport at Midsummer, its

season being announced, as the old fisherman who lived on it and by it,

generally known as “Old Hopewell,” told me, by the arrival of the

fireflies. He has taken nineteen salmon, of from eight to eighteen

pounds weight, in one morning with the fly. It offers no sport to speak

of now; the saw mills and their obstructive dams have quite cut off the

fish from their spawning grounds.

To the eastward, between

Halifax and Cape Canseau, occurs a succession of fine rivers, running

through the most extensive forest district in the province. The salmon

rivers of note are the Musquodoboit, Tangier river, the Sheet Harbour

rivers, and the St. Mary's. There are no important settlements on the

sea-coast, which is very wild and rugged to the east of Halifax, and

consequently they are less looked after and more poached. Formerly they

teemed with salmon. Besides the mill-dams, they are netted right across,

and the pools are swept and torched without mercy by settlers and

Indians. The St. Mary’s is the noblest and most beautiful river in Nova

Scotia, and its salmon are the largest. The nets overlap one another

from either shore throughout the long reaches of intervale and wild

meadow, dotted with groups of elm, which constitute its noted scenic

charms, and the lumbermen vie with the Indians in skill in their nightly

spearing expeditions by the light of blazing birch-bark torches.

There are many other fine

rivers besides those mentioned discharging into the Atlantic, which the

salmon has long ceased to frequent, being completely shut out, and which

would swell the dreary record of the ruin of the inland fisheries of

Nova Scotia. In these waters, at a distance from the capital, “Halifax

law,” as the settlers will tell you, is “no account’ The spirit of

wanton extermination is rife ; and, as it has been well remarked, it

really seems as though the man would be loudly applauded who was

discovered to have killed the last salmon.

Salmon are abundant in

the Bay of Fundy, which washes a large portion of Nova Scotia, but its

rivers are generally ill adapted for sport. Running through flat

alluvial lands, and turbid with the red mud, or rather, fine sand, of

the Bay shores, they are generally characterised by an absence of good

stands and salmon pools. The Annapolis river was once famous for salmon

fishing. On its tributary, the Nictaux, twenty or thirty might be taken

with the fly in an afternoon ; and the Gaspereau, a very picturesque

stream entering the Basin of Minas at Grand Pre, the once happy valley

of the French Acadians, still affords fair sport.

We will now turn to the

rivers of the Gulf which enter it from the mainland on the shores of New

Brunswick, Lower Canada, and Labrador, commencing with those of the

former province.

Proceeding along the

eastern shore of New Brunswick from its junction with Nova Scotia, we

pass several fine streams with picturesque scenery and strange Indian

names, which, once teeming with fish, now scarcely afford the resident

settler an annual taste of the flesh of salmon. The Miramichi, however,

arrests our attention as being a noble river; its yield and exportation

of salmon is still very large. Winding sluggishly through a beautiful

and highly cultivated valley for nearly one hundred miles from tlie

Atlantic, tlie first rapids and pools where fly-fishing may be practised

occur in the vicinity of Boiestown; here the sport afforded, in a good

season, is little inferior to that which may be obtained on the

Nepisiguit. One of its branches, also, the north-west Miramichi, is

worth a visit; and I have known some excellent sport obtained on it in

passing through to the Nepisiguit, from which river the water

communication for a canoe is interrupted but by a short portage through

the forest. .

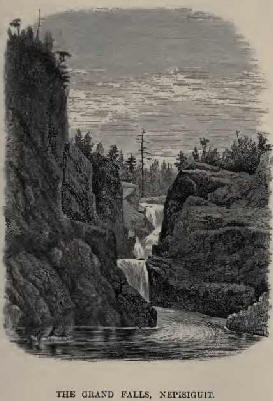

It is, however, on

entering the southern expanses of the beautiful Bay of Chaleurs that we

first find the paradise of the salmon-fisher; and here still, despite of

many foes—innumerable stake-nets which debar his entrance, the sweeping

seine in the fresh water, the torch and spear of the Indian tribes, and

lastly, and perhaps the least destructive agent, the tackle of the

fly-fisher-man—the bright foamy waters of the Nepisiguit, the

Restigouche, the Metapediac, and many others, repay the visitor and

sportsman, whence or how far soever he may have come, by the sport which

they afford, and by the wild scenery which surrounds their long course

through the forests of New Brunswick.

And, first, of the

Nepisiguit. This now famous river, which of late years has attracted

from their homes many visitors, both English and American, to spend a

few weeks in fishing and pleasantly camping-out on its banks, discharges

its waters into the Baie des Chaleurs at Bathurst, a small neat town,

easily accessible from either Halifax, St. John, or Quebec, and by

various modes of conveyance—coach, rail, and steamboat. Rising in the

centre of northern New Brunswick, in an elevated lake region which gives

birth to the Tobique and Upsal-quitch, rivers of about equal size, the

Nepisiguit has an eastward course of nearly one hundred miles through a

wilderness country, where not even a solitary Indian camp may be met

with. It is one of the wildest of American rivers; sometimes contracted

between cliffs to the breadth of a few yards, coursing sullenly and

darkly below overhanging forests, and sometimes, though rarely,

expanding into broad reaches of smoothly-gliding water—its most common

feature is the ever-recurring cascade and rapid.

The adventurous fisherman

will do well to supplement his sport on the river by embarking on a long

journey through the solitudes of the interior to its parent lakes. A

short portage of a couple of miles, and the canoe floats on the Tobique

lakes, and thence descends the Tobique through another hundred miles of

the wildest and most beautiful scenery imaginable. At the junction of

this latter river with the broad expanse of the upper St. John,

civilisation reappears; the traveller changes his conveyance for the

steamer or coach, and the frail canoe returns, with her hardy and

skilful sons of the river, to battle with the rocks and rapids of the

toilsome route.

The whole of this tour

is, however, fraught with interest to the sportsman and lover of wild

scenery. Moose, cariboo, and bear are invariably met with; the two

former being generally seen bathing in the water in the evenings, whilst

a visit from a bear at night is by no means an uncommon occurrence at

some camp or another on the way; or, perchance, Bruin may be surprised

when gorging in the early morning, breakfasting amongst the great

thickets of wild raspberries which abound on the banks. A little search,

up the tributary brooks will discover the wonderful works of beaver now

in progress; and other frequenters of the river, mink, otters, and

musquash, are plentiful, and frequently to be seen. In July and August

the young flappers of many species of duck form an agreeable change in

the daily bill of fare ; and though salmon do not ascend the Nepisiguit

beyond the Grand Falls, twenty-one miles from Bathurst, they may be

taken at the head waters of the Tobique; whilst river trout of large

size, and affording excellent sport, will greedily rise at an almost

bare hook throughout the whole extent of water.

Reclining in the bottom

of the canoe, the position of the traveller is most comfortable, and he

may make notes or sketches, as fancy leads him, with ease; indeed, from

the facility with which all necessaries and even luxuries may be

conveyed, but little hardship need be anticipated in a canoe voyage

through the rivers of northern New Brunswick.

The length of the journey

just described much depends on the state of the water and the number of

the party. With good water a canoe will get through with two sportsmen,

two canoe men, and all their goods —camps, blankets, and provisions—in

ten or twelve days; but should the rivers be low, two canoes must be

employed by the same number. A few years since I took a still more

northern route to the upper St. John, vid the Restigouche and Grand

River; the head-waters were so shallow that we literally had to drag our

canoe, fixed on long protecting slabs of cedar, for some days over the

rocky bed; we were, moreover, nearly starved, and occupied nearly three

weeks in reaching Fredericton on the St. John, down whose broad, deep

stream, however, we paddled at the rate of fifty miles a day.

The scenery on this line

of water-communication with the St. John, is grander, but not so wild as

on the former route, which I recommend as possessing many advantages,

particularly in the way of sport.

Mais revenons d nos

saumons—to describe the capabilities of the Nepisiguit to afford sport

to the salmon-fisher, and direct the visitor. The ascent of salmon in

this river is restricted to twenty-one miles of water by an insuperable

barrier—the Grand Falls ; but from the head of the tide, two miles above

the town, to this point, are a succession of beautiful pools with every

variety of water, so stocked with fish, and with such picturesque

surrounding scenery, that the eye of the sportsman who may happily

combine the love of nature with the lust of sport drinks in constant and

ever-varying delight as he is introduced to these bewitching spots. And

now of the pools seriatim.

Two miles above Bathurst

we come to the “Rough Waters,5’ where there is good fishing. No camp is

needed here ; for it is so near the accommodation of a comfortable

hotel, that I question whether any one would care to experiment, except

for novelty. It is a pretty spot, and the dark water here and there

breaks into pure white foam as it passes over a ledge which crosses the

channel from the steep red sandstone cliffs opposite. A short distance

above are the “Round Rocks,” with little falls and intervening pools,

where the river begins to show its true character; and here, as at the

last-mentioned spot, a good day’s fishing may be obtained from the town.

But one is now-a-days liable to interference, however, for of late years

the little ragged urchins from the Acadian settlement on the south shore

have imbibed a strong love of sport in addition to their hereditary

poaching propensities, and with a rough pole, a few yards of coarse

line, and a bait in appearance anything but a salmon fly, they will hook

some dozen or more salmon in a day when they are running freely, of

course losing nearly every fish.

Distant eight miles from

Bathurst, and accessible by a fair waggon road, are the Pabineau Falls,

one of the choicest fishing stations on the river. The scenery here is

most beautiful; the forest has now claimed the banks, and, as the.

stranger emerges from its shade, and stands on the broad, smooth

expanses of light grey and pink rocks which slope from him towards the

brink of the stream, viewing its clear grass-green waters rolling in

such fierce undulations over long descents, and thundering, enveloped in

mist, through various contracted passes into boiling pools, with

congregated masses of foam ever circling over their black depths, he

becomes impressed with the idea of irresistible power, and is

constrained to acknowledge that he stands in the presence of no ordinary

stream, but of a mighty river.

I have here stood by the

margin of the water, where hundreds of tons momentarily rushed past my

feet in a compact mass, and watched the bright gleam of the salmon' as

they would dart up from below like arrows to encounter the fall; a

slight pause as they near the head; another convulsive effort, and they

are safely over; but many fall back, at present unequal for the contest,

into the dark pool.

There are several

well-built bark shanties on the rocks above the falls, for the fine

scenery, and the ease with which the numerous pools in the neighbourhood

of the Pabineau can be fished, have made this a favourite haunt for

anglers.

THE PABINEAU FALLS, RIVER NEPISIGUIT.

Two miles above are the

Beeterbox Pools, where there is some swift, deep water at a curve in the

river, and at the foot of a long reach of rapids. It is a very good

station to fish, en passant, but not of sufficient extent to induce more

than an occasional visit.

“Mid-landing” is the next

spot where good sport may be obtained, particularly at the end of July,

when the river becomes low. The great depths of water here, shaded by

high rocks, induce large fish to remain long in these cool retreats.

Very small, dark flies, and the most transparent gut must be used; and

with these precautions, when other pools have been failing in a dry

season, I have taken half a dozen salmon a day from the deep waters of

Mid-landing, and from the long, rough rapid which runs into the pool.

Three miles above are the

“Chains of ^Rocks,” the great and the little. A camp below the last fall

of the lower chain will command all the pools. This range of pools

contains an abundance of fish. Below the fall is a long expanse of

smooth water, at the head of which salmon congregate in great numbers

preparatory to ascending the rough water above ; they lie in several

deep, eddying pools, where projecting ledges narrow the channel, and may

be seen flinging themselves out of water throughout the day. Above this

long series of cascades which fall over terraces of dark rocks, for

nearly half a mile, there is some evenly-gliding water, in which fish

may be taken from stands on the left bank. Here, and at the little chain

just above, is my favourite resort at this part of the river; there is

excellent camping-ground in the tall fir-woods on the north shore, and

bold jutting rocks command the pools admirably.

Between this spot and the

Basin, two miles above, there are but few spots where the fly may be

cast profitably ; and, taking the bush-path which skirts the river, we

may now shoulder our rods, and trudge up to the Grand Falls, our canoes

following, spurting through the rapid water in long strides as they are

impelled by the vigorous thrusts of the long iron-shod fir-poles. The

Basin is a broad and deep expansion of the river, and a reservoir where

the salmon congregate in multitudes, ultimately spawning at the entrance

of numerous gravelly brooks which flow into it from the surrounding

forest, and daily making sorties to the Falls, a mile above, to enjoy

the cool water which flows thence to the lake between tall, overhanging

cliffs, sometimes completely shaded from the sunlight save during a very

limited portion of the day.

In this mile of deep

swift water, which winds in a dark thread from the Basin to the foot of

the falls between lofty walls of slate rock, salmon lie during the day

in thousands; there are certain spots which they prefer, found by

experience to be the best pools, where the splash of the fish and the

voice of the angler awaken echoes from the cliffs throughout the season.

Fine fishing, and fine tackle for these—aye, and a good temper, too—for

it is the most favoured resort for rods, and we may often be compelled

to cease awhile from our sport, whilst a canoe (here the only mode of

conveyance from pool to pool) with its scarlet-shirted paddlers, creeps

through the water by the opposite shore.

There are but one or two

places in the cliffs here where a camp may be pitched, and, if these are

occupied, we must drop down-stream again to some less-frequented

locality. The best of these is a green sloping bank, over which a cool

brook courses between copses of hazel and alder into the river below. It

is a charming situation, and from a grassy plateau overhanging the

river, where the camps are usually placed, we may look down into a clear

pool, some seventy feet below, and watch the salmon which occupy it,

dressed in distinct ranks.

The Grand Falls are

rather more than 100 feet in height. The river, here greatly contracted,

descends into a deep boiling pool, first by a succession of headlong

tumbles, and then in a compact and perpendicular fall of forty feet. The

first fishing pool is just below the eddying basin at the foot of the

fall, which is seldom entered by the canoe men, as currents both of air

and water sweep round it towards the pitch; besides, the fish here are

so engaged in battling with the heaving water, in their vain attempts to

surmount the falls, that they will not regard the fly.

All this portion of the

Nepisiguit must be fished from a canoe, excepting a few rocky stands,

where almost every cast is made at the risk of the hook snapping against

the cliffs behind; and this leads us to say a few words on the canoe men

of the river. They are a hardy and generally intelligent race of

Acadian-French, apparently a good deal crossed with Indian blood,

exceedingly skilful in managing their bark canoes, and in getting fish

for the sportsman; they have great experience in the requirements of a

camp in the woods, and are, withal, very merry, companionable fellows.

For a fishing camp anywhere above the Pabineau, a canoe and three men

(one to act as cook and camp-keeper), are indispensable; and on arriving

at Bathurst, the services of any of the following men of good character

should be secured : The Chamberlains, the Yineaus, David Buchet? Joe

Young, and others; Baldwin, the landlord of the little hotel, knows them

all well. Their wages are a dollar a day for the canoe men ; the cook

may be hired for half a dollar, but he will grumble, and most likely

succeed in getting three shillings. If a voyage through to the St. John,

vid the Nictaux and Tobique lakes, be contemplated, selection should be

made of those men who have taken parties through before. All provisions

necessary for a sojourn on the river—everything, from an excellent ham

to a tin of the best chocolate—are to be had at the store of Messrs.

Ferguson, Rankin, and Co., in Bathurst, obliging people, very moderate

and liberal; they will deduct for all the cooking utensils, supplied by

them, which may be returned on coming down the river.

Notwithstanding the

immense destruction of fish in the Nepisiguit in every possible

way—netting and torching in fresh water, whenever the nature of the

stream allows of such proceedings, wholesale sweeping and spearing on

their spawning beds by tribes of Indians, even into the month of

November, when they are quite black and slimy, extensive netting at its

mouth, and the number taken by fiy-fishers—even yet the river swarms

with salmon; a favourable condition of the water and the command of a

few pools will insure good sport. The fish are not very large, as in the

more northern rivers of the bay; the average of the weights, of seventy

salmon killed by one rod at the Grand Falls a few seasons since, was

11lb. 8oz.; and of thirty grilse, 41b. The fish commence running up in

June, but, from the height of the water, there is rarely good fishing

before July; the 10th is about the best time, and by that time they have

gone up as high as the Grand Falls. The flies for the Nepisiguit should

be small and neat, and of three sizes to each pattern, for different

states of water. As mistakes are often made from the different mode of

numbering by different makers, it will be sufficient to say that the

length of the medium fly should be 1-fin. from the point of the shank to

the extreme bend, measuring diagonally across. The patterns should be

generally dark, and all mixed wings should be as modest as possible; no

gaudy contrasts of colour, as used in Norway or Scotland, will do here.

A dark fly, tied as follows, is a great favourite: body of black mohair,

ribbed with fine gold thread, black hackle, very dark mallard wing, a

narrow tip of orange silk, and a very small feather from the crest of

golden pheasant for a tail. Then I like a rich claret body with dark

mixed wing and tail, claret hackle, and a few fibres of English jay in

the shoulder. Small grey-bodied flies ribbed with silver, grey legs, and

wing mixed with wood-duck and golden pheasant, will do well. Many other

and brighter flies may be used in the rough water, and a primrose body,

with black head and tip, and butterfly wing of golden pheasant, will

prove very tempting to grilse, which, late in July, may be taken in any

number in many parts of the river, particularly at the Pabineau and

Chain of Rocks. These flies will do anywhere in New Brunswick.

At the head of the Bay of

Chaleurs, and about fifty miles from Bathurst, we come to the

Restigouche, one of the largest rivers of British North America, 220

miles in length, and formerly teeming with salmon from the sea to its

upper waters. So abundant were the fish some twenty-five years ago, that

Mr. Perley, Her Majesty's Commissioner for the Fisheries, states that

3000 barrels were shipped annually from this river, and in those days

salmon of 60lb. weight were not uncommon. Of late years there has been a

sad falling-off, and instead of eleven salmon going to a barrel of

200lb., more than twice the number must now be used. Unfortunately for

the preservation of the fish, and the prospects of the fly-fisher, the

character of this beautiful river is very different to that of the

Nepisiguit. For 100 miles the Restigouche runs in a narrow valley

between wooded mountains with an almost unvarying rapid current, with

but few deep pools and no falls. Hence the chances of rod-fishing are

greatly diminished, whilst settlers and Indians torch and spear

everywhere. The channel is much used by the lumberers for the

water-conveyance of provisions to the gangs employed in the woods at its

head-waters—scows {i.e., large flat-bottomed barges) being employed,

drawn by teams of horses which find a natural tow-path in its shingly

beaches by the edge of the forest. High up the river there are many

rifts and sand-beaches, partly exposed in a dry season, through which

the channel winds ; and the scow is often dragged through shallow

places, thus ploughing up the spawning grounds of the salmon.

A few years since, after

a fortnight’s fishing on the Nepisiguit, during which my companion and

myself took eighty salmon, notwithstanding an unprecedented drought, we

visited the Restigouche, more for the sake of enjoying its fine scenery

than expecting sport. Staying for a day, however, at the house of a

hospitable farmer who dwelt by the river-side, at the junction of the

Matapediac with the main stream, I had the pleasure of hooking the first

salmon ever taken with a fly in the Restigouche water, a fine clean fish

of twelve pounds. In an hour’s fishing I had taken three salmon, each

differently shaped, and at once pronounced by my host to be frequenters

of three separate rivers which here unite—the two already mentioned and

the Upsal-quitch.

The Matapediac has a

course of sixty miles from a large lake in Rimouski, Lower Canada, and

the Upsal-quitch runs in on the New Brunswick side. They are both fine

rivers, and ascended by salmon in large numbers; the latter is stated to

be very like the Nepisiguit in character—full of falls and rapids, and I

believe it would afford equal sport. It looked most tempting as we

passed its mouth on our long canoe voyage up the main river, but we had

not time to stay and test its capabilities. About sixty miles from the

sea we discovered a salmon pool in the Restigouche, and took eight small

fish from it in an afternoon ; but such pools are few and far between,

and I would not recommend any one to ascend this river for sport above

the Upsalquitch. The flies we used here were dark clarets and reds; I

believe any fly will take, recommending, however, larger sizes than the

Nepisiguit flies, as the Restigouche salmon run much larger, and even in

these days commonly weigh thirty pounds.

Campbelltown, a neat

little village at the head of the tide, twenty miles from the sea, is to

be reached from Bathurst by coach; and here the traveller or sportsman

intending to ascend the Restigouche or its before-mentioned tributaries,

will find a large settlement of Indians of the Micmac tribe. They all

have canoes, and many of them are good guides, and trustworthy. There is

a good store at which to purchase provisions, and a very comfortable

little hotel kept by a Mr. M‘Leod.

We now leave the rivers

of New Brunswick: the Restigouche being the dividing line between the

two provinces, the rivers of the north shore of Chaleurs Bay are

Canadian. About thirty miles from the head of the bay we come to the

Cascapediac, a large river running in a deep chasm through the mountains

of Bonaventure. It is frequented by salmon of large size, and I have

been told by Mr. R. EL Montgomery, who resides near its mouth, that the

average weight is between thirty and forty pounds. He offered to procure

me good Indians and canoes for ascending to the first rapids, which are

some distance up the river. The whole district of Gaspe is intersected

by numerous and splendid rivers, abounding in salmon and sea trout, the

latter of four pounds to seven pounds in weight. The mountain scenery

through which they flow is magnificent, and many of them have never been

thrown over with a fly rod. Amongst the largest may be noticed the

Bonaventure, the Malbaie, and the Magdeleine.

On the south shore of the

St. Lawrence, from Gaspd to Quebec, these are several streams which

formerly abounded in salmon, but of late years have been so unproductive

that attention need not be directed to them. From the Jacques Cartier, a

few miles above Quebec, to the Labrador, the north shore of the St.

Lawrence is intersected by innumerable rivers ; in many of these the

salmon fishery has been nearly destroyed, but the energy of the Canadian

Government is fast remedying the evil. The process of reproduction by

artificial propagation under an able superintendent, and the

preservation of the rivers, are bringing back the salmon to comparative

plenty in many a worn-out stream; and the visitor to Quebec will soon be

enabled to obtain sport on the beautiful Jacques Cartier and other

rivers in the neighbourhood, without having to seek the distant fishing

stations of the Labrador. The Saguenay, too, with its thirty

tributaries, is improving; for many years past this noble river has

scarcely proved worth a visit, except for its wonderful scenery. In

fact, the legislature, aided by an excellently constituted club for the

protection of fish and game, have taken the matter up in earnest;

fish-ways are placed on those rivers which have dams or slides upon

them; netting and spearing in the fresh water is prevented; an able

superintendent of fisheries, and several overseers, have been appointed

; and, finally, an excellent measure has been adopted—the annual leasing

of salmon rivers to gentlemen for fly-fishing, for small rents—on

condition of their aiding and carrying out the proper preservation of

the fisheries.

Amongst the largest and

most notable salmon rivers which are passed in proceeding from the

Saguenay along the northern shore are the Escoumins, Portneuf,

Bersia-mits, Outardes, Manacouagan, Godbout, Trinity, St. Margaret,

Moisie, St. John, Mingan, Natashquan, and Esquimaux. Salmon ascend all

these rivers, and take the fly readily. Whether they will rise in the

rivers of the north-eastern coast, past the straits of Belle-Isle,

remains to be proved. It has been affirmed that they will not do so in

the Labrador rivers of high northern latitude, thus evincing the same

peculiarity which has been observed on the part of the true sea salmon

of Siberian rivers flowing into the Arctic Ocean. I have heard, however,

that they will rise at a piece of red cloth trailed on a hook over the

water from the stem of a boat.

In conclusion, the salmon

rivers of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, though they offer no extraordinary

sport, possess the charms of wild and often noble scenery; life in the

woods, in a summer camp, will agreeably surprise those who hold back for

fear of hard work, and the discomforts of “ roughing it.” Any point,

excepting the extremes of Labrador, may be reached with ease from either

Quebec or Halifax ; whilst the economy which may be practised by a party

of two or three, will be found to be within the means of most sportsmen.

At the termination of the fishing season a few weeks may be spent in

tourising through the Canadas or the States; and in the nionth of

September the glowing forests of Nova Scotia or New Brunswick may be

traversed in search of moose, cariboo, or bear. Between the Ottawa and

the great lakes there is excellent duck-shooting, and the woods abound

in deer (Cervus Yirginianus), whilst the vast expanses of wilderness in

Newfoundland teem with cariboo, ptarmigan, and wild fowl; the former so

abundant as sometimes to tempt the sportsman (?) to kill more than

he can carry away or