|

THE CARIBOO

(.Rangifer, Hamilton Smith; Rangifer Caribou, Audubon and Bachman.)

Muzzle entirely covered

with hair; the tear bag small, covered with a pencil of hairs. The fur

is brittle; in summer, short; in winter longer, whiter; of the throat

longer. The hoofs are broad, depressed, and bent in at the tip. The

external metatarsal gland is above the middle of the leg. Horns, in both

sexes, elongate, subcylindric, with the basal branches and tip dilated

and palmated; of the females smaller. Skull with rather large nose

cavity; about half as long as the distance to the first grinder; the

intermaxillary moderate, nearly reaching to the nasal; a small, very

shallow, suborbital pit.

The above diagnosis,

taken from Dr. Gray’s article on the Buminantia in the Knowsley

menagerie, seems to embrace the chief characteristics of the reindeer of

the sub-arctic regions. The colour, habits, &c., of the variety

designated above will be found succeeding the following general

considerations. As a species subject to but slight local variation (with

one possible exception in the case of the barren ground cariboo) the

reindeer, Cervus tarandus of Linnaeus, rangifer of Hamilton Smith,

inhabits both the old and the new worlds under similar circumstances of

climate and natural productions. Its range across the Northern

continents of Asia, Europe and America is almost unbroken; whilst in the

North Atlantic, which presents the only serious interruption to its

circumpolar continuity, it occurs in Iceland, Greenland and

Newfoundland. Sometimes preferring the barren heights of the Norwegian

fells, or the elevated plateaux of Newfoundland, at others the seclusion

of the pine forest (as with the woodland cariboo of America), its haunts

and boundaries are always-determined by the distribution of those mosses

and lichens which almost exclusively constitute its food—the Cladonia

rangiferina or reindeer lichen, with two or three, species of

Cornicu-laria and Cetraria.

When we consider the

great antiquity of the reindeer, and its occurrence as a true fossil

mammal coeval with the mammoth and other gigantic animals now extinct,

in connection with its singular adaptation to feed on lichens—those

representatives of a primitive vegetation which are still engaged in

preparing a soil for higher forms in northern latitudes—we cannot fail

in recognising its mission as an animal of the utmost importance in

affording food and clothing to the primitive races of mankind of the

stone age. With its remains discovered in the bone caves and drift beds

of that period are associated stone arrow-heads and bone implements ;

whilst a resemblance of the animal, fairly wrought upon its own horn,

leaves no room to doubt its uses as a beast of the chase, though

probably not (in those savage times) of domestication.

Even in Caesar’s day

ancient Gaul was a country of gloomy fir forests and extensive morasses,

and its climate more like that of Canada at present. The reindeer also

was still abundant throughout central Europe (though probably it had

long since disappeared from Great Britain and the south of France), and

was in a state of gradual migration to its present northern haunts. A

more essentially arctic deer than the elk, the reindeer, in its southern

extension, is found with the latter animal co-occupant of the wocfded

regions which succeed the desert plains on the shores of the Polar

ocean, termed “barren grounds” on the American continent, and “Tundras”

in Europe and Asia. Its most southern limit in the Old World is reached

in Chinese Tartary in lat. 50°. A fact mentioned in the Natural History

Review, in an article on the Mammalia of A moor land, may be here quoted

as showing a singular meeting of northern and southern types of animal

life. It is stated that the Bengal tiger, ranging northwards

occasionally to lat. 52°, there chiefly subsists on the flesh of the

reindeer, whilst the tail-less hare (pika) a polar resident, sometimes

wanders south to lat. 48° where the tiger abounds.

Following an ascending

isotherm through Siberia and Northern Russia, the reindeer comes down on

the elevated table-lands of Scandinavia to latitude 60°, “ wherever,” as

Mr. Barnard observes in “Sport in Norway,” “the altitude is above the

limit of the willow and the birch.” From the latter country the animal

was successfully introduced into Iceland in 1770 (a similar attempt

being made at the same time to acclimatize it in Scotland, which ended

in failure), and has since so multiplied as to be regarded with

disfavour by the inhabitants, who care little for it as a beast of the

chase, on account of the damage it does to the grasses and Iceland moss

on the plains. According to Professor Paijkull, author of “A Summer in

Iceland,” the desert plains south of Lake Myvatn are its principal

resort.

Crossing the Atlantic

to the south of Greenland, which is inhabited by the variety (or species

R. Groenlandicus, the American reindeer, now termed ‘the cariboo, is

first met with in Newfoundland. It is abundant on the elevated plateaux

and extensive savannahs of this great island, and is sometimes seen on

the cliffs even at Cape Race.

The most southerly

range attained by the species on the Atlantic seaboard of North America

is determined at Cape Sable in Nova Scotia, in lat. 43° 30', or about

that of Marseilles. In this province the cariboo is becoming very

scarce, and almost altogether restricted to the high lands of Cape

Breton, and the Cobequid range of hills. It is not found in Prince

Edwards Island or in Anticosti.

Tolerably abundant in

New Brunswick and the adjoining portion of Canada south of the St.

Lawrence to the latitude of Quebec, of rarer occurrence in the State of

Maine, we find the home of the woodland cariboo in the great belt of

coniferous forest which in Upper and Lower Canada extends northwards

from the basin of the St. Lawrence over an immense wilderness country,

and embraces the southern area of the Hudson's Bay basin. From the

western shore of Lake Superior, and at some distance back from the

prairie country, the line of its range across the continent curves to

the northwest, following the rapidly ascending isotherm into the Valley

of the Mackenzie, and thence crossing the Rocky Mountains, passes into

the American territory of Alaska.

According to Mr. Lord

it inhabits the high ridges of the Cascade Mountains, the Galton range

and western slope of the Rocky Mountains in British Columbia.

In evidence of the

transmission of the cariboo into Eastern Asia, it is stated by Dr.

Godman that it crosses from Behring's strait to Kamschatka by the

Aleutian islands.

Closely associated with

man in a state of semidomestication in Siberia and Lapland, the wild

rein-deer also largely contributes to the support of the various nomadic

tribes of these countries, by whom it is slaughtered on the paths of its

two great annual migrations. In America likewise, though no attempt has

been made to convert the cariboo into a beast of burden, its flesh is

the mainstay of many wandering Indian tribes who inhabit the subarctic

forest region from Labrador to the northern spurs of the Rocky

Mountains, and its skin their principal resource for clothing. In its

distribution across the American continent, indicated above, it is

pursued in the chase by the Montagnais and Nasquapee Indians of

Labrador, the Crees and Chipewyans of Hudson’s Bay, and the Dog-ribs and

other tribes of the Mackenzie Valley. To the Micmacs, Malicites and

others, south of the St. Lawrence, it is no longer indispensable as a

staple of subsistence; they are now intimately associated with the

civilisation of the white man, who completely possesses their

hunting-grounds, and with whose mode of life they partially comply; but

to the wilder races designated above, its gradual disappearance must

bring starvation and a corresponding progress towards extinction.

With regard to the

barren ground cariboo (E. Groenlandicus) being distinct from the larger

animal of the forests, the separation of the two as species by Professor

Baird of the Smithsonian Institution at Washington in the description of

North American mammals, which accompanies the War Department Reports of

the Pacific Route, joined with the opinion expressed by Sir John

Bichardson in his “Journal of a Boat Voyage through Rupert’s Land and

the Arctic Sea," and the further testimony of Dr. King, surgeon to

Back's expedition, appears to leave no room for doubt. Mr. Baird says “

the animal is much smaller than the woodland reindeer; the does not

being larger than a good sized sheep/’ The average weight of ninety-four

deer shot in one season by Captain M'Clintock’s men, when cleaned for

the table, was sixty pounds. “A full-grown, well-fed buck,” says Sir J.

Bichardson, “seldom weighs more than one hundred and fifty pounds after

the intestines are removed. The bucks of the larger kind which were

mentioned as frequenting the spurs of the Rocky Mountains, near the

Arctic circle, weigh from two hundred pounds to three hundred pounds,

also without the intestines.” He also states that “ this kind does not

penetrate far into the forest even in severe seasons, but prefers

keeping in the isolated clumps or thin woods that grow on the skirts of

the barren grounds, making excursions into the latter in fine weather.”

Dr. King mentions that the barren-ground species is peculiar not only in

the form of its liver, but in not possessing a receptacle for bile. This

species ranges along the shores of the Arctic Ocean and of Hudson’s Bay,

above the northern limit of forest growth; it inhabits Melville and

other islands of the Arctic archipelago, and is found in Greenland.

The cariboo of the

forests of Lower Canada, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, which we now

proceed to describe, seems to attain in this portion of America, the

finest development of which the species is susceptible. It is a

strongly-built, thick-set animal, (that is by comparison with the more

graceful of the Cervidae), yet far from being as ungainly and slouching

as the Norwegian reindeer is commonly depicted in drawings, though these

are probably generally taken from domesticated specimens, which they

resemble much more closely than they do the wild deer of the mountains.

A very large buck in Newfoundland will exceed four hundred pounds in

weight, and measure over four feet in height at the shoulder. I have

seen a cariboo in Nova Scotia that must have considerably exceeded four

feet six inches in height, and was thought by the Indian at a distance

off to have been a moose.

Reindeer of a similar

development, and in colour closely resembling the cariboo of Eastern

America, were met with by Erman in Eastern Asia, where they are used for

the saddle (placed on the shoulder—the only part of the back where the

deer can support a load) by the Tunguzes. He states that the Lapland

reindeer of menageries and museums appeared to him but dwarfs in

comparison with those of Northern Asia, and with their size and strength

seemed also to have lost much of their beauty of form. Certainly the

cariboo of Nova Scotia or New Brunswick, as I have seen them, gracefully

trotting over the plains on light snow, and in Indian file, or, when

alarmed, circling round the hunter with neck and head braced up and scut

erect, stepping with an astonishing elasticity and spring, is a noble

creature in comparison with the specimens of the reindeer of Northern

Europe that have appeared in the Society's gardens at Regent's Park:

they are, nevertheless, indubitably the same species and simply local

variations.

The colour of the

American cariboo, as described by Audubon and Bachman, is as follows :—

“Tips of hairs light

dun gray, whiter on the neck than elsewhere ; nose, ears, outer surface

of legs and shoulders brownish. Neck and throat dull white; a faint

whitish patch on the side of shoulders. Belly and tail white; a band of

white around all the legs adjoining the hoofs.” From this general

description there is, however, considerable variation. Bucks in their

prime are often of a rich, rufous-brown hue on the back and legs, having

the neck and pendant mane, tail and rump, snow-white. A patch of dark

hair, nearly black, appears on the side of the muzzle and cheek. As the

hair grows in length, towards the approach of winter, it lightens

considerably in hue: individuals may frequently be seen in a herd with

coats of the palest fawn colour, almost white. Young deer are dappled on

the side and flank with light sandy spots. The white mane, reaching to

over a foot in length in old males, which hangs pendant from the neck

with a graceful one of the handsomest of animals; for when one sees a

Tunguze sit, with the proudest deportment, on his reindeer, they both

seem made for each other, and it is hard to decide whether the reindeer

lends grace to the rider or borrows it from him.”—Travels in Siberia, by

Adolph Erman.

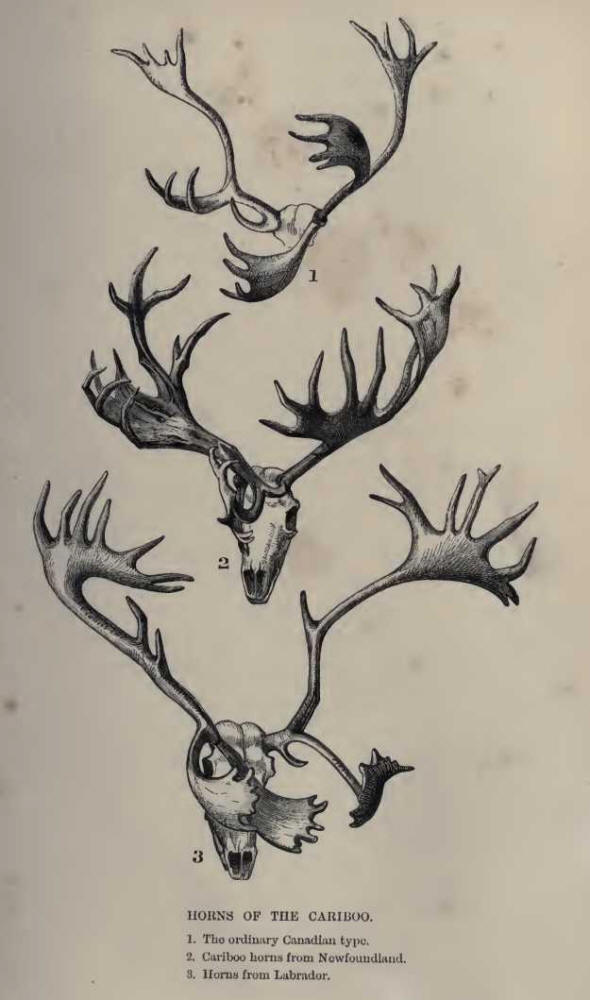

The horns of different

specimens vary greatly in form both as regards the development of

palmation and the position of the principal branches. As a general rule,

the horns of the Norwegian reindeer are (according to my impression)

less subject to palmation of the main shaft, which is longer, and

broadens only at the top where the principal tines are thrown off. I

have, however, met with precisely the same form in antlers from the

Labrador. The accompanying figures will illustrate the forms alluded to.

The middle snag of the cariboo’s horn is also more developed than in the

case of the European variety.

In most instances there

is but one well-developed brow antler, the other being a solitary curved

prong; sometimes, however, as shown in the illustration, very handsome

specimens occur of two perfect brow snags meeting in front of the

forehead, the prongs interweaving like the fingers of joined hands.

Except in the case of

the does and young bucks, which retain theirs till spring, it is seldom

that horns are seen in a herd of cariboo after Christmas. The reason to

which the retention of the horns by the female reindeer during winter

has been attributed by some speculative writers—namely, in order to

clear away the deep encrusted snow, and enable her fawns to get at the

moss beneath —is simply wrong. The animal never uses any other means

than its hoofs to scrape for its moss; whilst the thin sharp prongs of

the doe would prove anything but an efficient shovel. The latter and

true mode of proceeding I have often watched when worming through the

bushes

round the edge of a

barren to get a shot. Both Mr. Barnard, and the author of “ Ten Years in

Sweden,” allude to the female reindeer using her horns in winter to

protect the fawns from the males, thus rightly accounting for this

singular provision of nature in the case of a gregarious species in

which the males, females, and young herd together at all seasons.

Another

misrepresentation has appeared with regard to the reindeer : it has been

compared, when obliged to cross a lake on ice, to a cat on

walnut-shells! I cannot conceive any variation in a point so intimately

connected with its winter habits on the part of the European reindeer,

if the two are, as I believe, identical in configuration and

subservience to existence under precisely similar circumstances; but for

the cariboo I can aver that its foot is a beautiful adaptation to the

snow-covered country in which it resides, and that on ice it has

naturally an advantage similar to that obtained artificially by the

skater. In winter time the frog is almost entirely absorbed, and the

edges of the hoof, now quite concave, grow out in thin sharp ridges;

each division on the under surface presenting the appearance of a huge

mussel-shell. According to “The Old Hunter,” who has kindly forwarded to

me some specimens shot by himself in Newfoundland in the fall of 1867

for comparison with examples of my own shot in winter, the frog is

absorbed by the latter end of November, when the lakes are frozen ; the

shell grows with great rapidity, and the frog does not fill up again

till spring, when the antlers bud out. With this singular conformation

of the foot, its great lateral spread, and the additional assistance

afforded in maintaining a foot-hold on slippery surfaces by the long

stiff bristles which grow downwards at the fetlock, curving forwards

underneath between the divisions, the cariboo is enabled to proceed over

crusted snow, to cross frozen lakes, or ascend icy precipices with an

ease which places him, when in flight, beyond the reach of all enemies,

except perhaps the nimble and untiring wolf.

The pace of the cariboo

when started is like that of the moose, a long, steady trot, breaking

into a brisk walk at intervals as the point of alarm is left behind. He

sometimes gallops, or rather bounds, for a short distance at first; this

the moose never does. When thoroughly alarmed, he will travel much

further than the moose; the hunter having disturbed, missed, or slightly

wounded the latter, may, by following him up, very probably get several

chances again the same day. Such is seldom the case in cariboo hunting,

even in districts where the animals are rarely disturbed. Once off,

unless wounded, you do not see them again.

The cariboo feeds

principally on the Cladonia rangi-ferina, with which barrens and all

permanent clearings in the fir forest are thickly carpeted, and which

appears to grow more luxuriantly in the subarctic regions than in more

temperate latitudes. Mr. Hind, in “ Explorations in Labrador,” describes

the beauty and luxuriance of this moss in the Laurentian country, “with

admiration for which,” he says, “the traveller is inspired, as well as

for its wonderful adaptation to the climate, and its value as a source

of food to that mainstay of the Indian, and consequently of the fur

trade in these regions—the caribou.” The recently-announced discovery by

a French chemist who has succeeded in extracting alcohol in large

quantities from lichens, and especially from the reindeer moss

(identical in Europe with that of America), is interesting? and readily

suggests the value of this primitive vegetation in supporting animal

life in a Boreal climate as a lieat-producing food. Besides the above,

which appears to be its staple food, the cariboo partakes of the tripe

de roche (Sticla pulmonaria) and other parasitic lichens growing on the

bark of trees, and is exceedingly fond of the Usnea, which grows on the

boughs (especially affecting the top) of the black spruce, in long,

pendant hanks. In the forests on the Cumberland Hills, in Nova Scotia, I

have observed the snow quite trodden down during the night by the

cariboo, which had resorted to feed on the “ old man's beards ” in the

tops of the spruces felled by the lumberers on the day previous. In the

same locality I have observed such frequent scratchings in the first

light snow of the season at the foot of the trees in beech groves, that

I am convinced that the animal, like the bear, is partial to the rich

food afforded by the mast.

I am not aware that a

favourite item of the diet of the Norwegian reindeer—Ranunculus

glacialis—is found in America, and the woodland cariboo has no chance of

exhibiting the strange but well-authenticated taste of the former animal

by devouring the lemming; otherwise the habits of the two varieties are

perfectly similar as regards food.

The woodland cariboo,

like the Laplander s reindeer, is essentially a migratory animal. There

are two well-defined periods of migration—in the spring and

autumn—whilst throughout the winter it appears constantly seized with an

unconquerable desire to change its residence.

The great periodic

movements seem to result from an instinctive impulse of the reindeer

throughout its whole circumpolar range. Sir J. Richardson, in America,

Erman and Yon Wrangell, in Northern Europe and Asia—the three

distinguished savants who have contributed so largely to the natural

history of the northern regions— all affirm the regularity of its

migrations to the open steppes, barren grounds, and bare mountains, and

point to the chief cause—a desire to escape the insupportable torments

of the flies which swarm in the forest. In Newfoundland the cariboo acts

in a manner precisely similar to that described by Wrangell, in speaking

of the reindeer of the Aniui. They leave the lake country and broad

savannahs of the interior for the mountain range which covers the long

promontory terminating at the Straits of Belleisle, at the commencement

of summer, and return when warned by the frosts of September to seek the

lowlands. At this time the deer passes, and valleys at the head of the

Bay of Exploits may be seen thick with deer moving in long strings; and

here the Red Indians of a past age, like the hunters of the Aniui, would

congregate to kill their winter's supply of venison.

With regard to the

restlessness of this animal at intervals in the forest country in winter

time, I have frequently observed a sudden and contemporary shift of all

the cariboo throughout a large area of country. One day quietly feeding

through the forest in little bands, the next, perhaps, all tracks would

show a general move in a certain direction; the deer joining their

parties after a while, and entirely leaving the district, travelling in

large herds towards new feeding-grounds, almost invariably down the

wind. The little Arctic reindeer of North America is far less migratory

in its habits than the larger species, and with the musk-sheep (ovibos)

remains in the same localities throughout, the year.

In forest districts, in

many parts of its range over the Northern American continent, the

cariboo is found together with the moose in the same woodlands. They

appear, however, to avoid each other's company; and I have observed in

following the tracks of a travelling band of cariboo, that, on passing a

fresh moose-yard, they have broken into a trot—a sure sign of alarm. In

many districts, especially those in which the existing southern limits

of the cariboo are marked, this animal is gradually disappearing, whilst

the moose is taking its place. To a great extent this is the result of

an increasing settlement of the country by man. The moose is a much more

domestic animal in its habits, and will remain and multiply in any small

forest district, however the latter may be surrounded by roads or

settlements ; whereas the cariboo is a great wanderer, and requires long

and unbroken ranges of wild country in which he can uninterruptedly

indulge his vagrant habits. Being moreover more jealous of the advance

of civilisation than the moose, he is surely disappearing as his old

lines of periodic migration are encroached upon and broken by new

settlements and their connecting roads.

In winters of great

severity the cariboo always travel to the southernmost limits of their

haunts, which they occasionally exceed and enter the settlements. Some

years ago, during an unusually cold winter, the deer crossed in large

bands from Labrador into Newfoundland over the frozen straits. As

assumed by Dr. Gray, a variety appears to be established in the case of

the Newfoundland

cariboo. These deer certainly attain a greater development than the

generality of the specimens shot on the continent: I have heard of bucks

weighing six hundred pounds, and even over. The general colour of the

former animals is lighter—to be accounted for, perhaps, by the fact that

Newfoundland is a far more open country than the eastern parts of Canada

and the Lower Provinces. The herds are moreover comparatively

undisturbed, and the moss grows in the greatest profusion. I have seen

the fat taken off the loins of a Newfoundland deer o the depth of two

inches. Further particulars concerning the cariboo on this island and

its migrations will be found in a chapter on Newfoundland. |