|

Objective of Aubers and

Festubert—Allies’ co-operation—Great French offensive—Terrific

bombardment—British support —Endless German fortresses—Shortage of

munitions —Probable explanation—Effect of Times disclosures— Outcry in

England—Coalition Government—After Ypres—The Canadian

advance—Disposition of Canadians—Attack on an Orchard—Canadian

Scottish—Sapper Harmon’s exploits—Drawback to drill-book tactics—A

Canadian ruse —“Sam Slick”—The Orchard won—Arrival of Second Brigade—The

attempt on “Bexhill”—In the German trenches—Strathoona’s Horse—King

Edward’s Horse— Cavalry fight on foot—Further attack on “Bexhill”—

Redoubt taken—“ Bexhill ” captured^—“ Dig in and hang on ”—Attack on the

“ Well ”—Heroic efforts repulsed— General Seely assumes command—A

critical moment— Heavy officer casualties—The courage of the cavalry—

Major Murray’s good work—Gallantry of Sergt. Morris and Corpl. Pym—Death

of Sergt. Hickey—Canadian Division withdrawn—Trench warfare till June.

“In records that defy

the tooth of time.”—The Statesman’s Creed.

To many minds the

battle of Festubert, sometimes called the battle of Aubers, in which the

Canadians played so gallant and glorious a part, represents only a vast

conflict which raged for a long period without any definite objective,

any clearly defined line of attack, and with no decisive result from

which clear conclusions can be drawn.

This unfortunate

impression is largely due to the fact that it is impossible at the

opening of a great battle for the commander to give any indication of

his intentions; that newspaper correspondents are debarred from

discussing them; and that the official despatches which reveal the

purpose and the plan of a battle, are only issued when the engagement

has already passed into history and has been lost sight of among newer

feats of arms.

As a matter of fact,

the battle of Festubert is, in all its aspects, one of the most clearly

defined of the war, notwithstanding the length of time that it covered

and the numerous and confused individual and sectional engagements

fought along its front. Its aim was clear, and it was a portion of a

definite scheme on the part of the Allies. The actual fight is perfectly

easy to follow, and the results are important, not only from the

military point of view (although in this respect Festubert must be

counted a failure), but from the political changes they produced in

England—changes designed for the better conduct of the war.

As I have already

explained, if we had completely broken the German lines at the battle of

Neuve Chapelle, we should have gained the Aubers Ridge, which dominates

Lille, the retaking of which would have completely altered the whole

aspect of the war on the Western front.

General Joffre had

determined on a great offensive movement in Artois, in May, for which

purpose he concentrated the most overwhelming artillery force up to this

time assembled in the West. It was on a par with the terrific masses of

guns with which von Mackensen was, about the same time, blasting his way

through Galicia. The French made wonderful progress, and only a few of

the defences of Lens, the key of the whole French objective, remained in

German hands. But the Germans were pouring reinforcements into the

south, and it was then that Sir John French, in conjunction with General

Joffre, moved his forces to the attack. This British offensive was

designed to hold up the German reinforcements destined for Lens, and at

the same time to offer the British a second opportunity for gaining the

Aubers Ridge, from which Lille and La Bassee could be dominated. If the

British could gain the ridge, which they hoped to secure at the battle

of Neuve Chapelle, and if the French could win through to Lens, the

Allies would then be in a position to sweep on together towards the city

which was their common goal.

The attack on the

German positions began on May 9th,1 and

continued through several days and nights, and waned, only to be renewed

with redoubled fury on May 16th. On May 19th, the 2nd and 7th Divisions,

which had suffered very severely, were withdrawn, and their places taken

by the Canadian Division and the 51st Highland Division (Territorial).

With the share of the battle which fell to the lot of the Canadians I

will deal in detail directly.

The British attack

failed to clear the way to Lille, which still remains in German hands.

With the reasons which resulted in our check at Neuve Chapelle I have

already dealt, and it is now necessary to consider the two principal

reasons which may be assigned for our second failure to secure the

all-important Aubers Ridge.

The first reason is

definite and explicable. The second reason is debatable.

At various points along

this sector of the front, and on many occasions, the German lines were

pierced—pierced but not broken. Again and again the British and Canadian

troops took the first, the second, and the third line German trenches.

This may have destroyed the mathematical precision of the German line,

but it only succeeded in splitting it up into a series of absolutely

impregnable fortins. It must be remembered that the Germans fought a

defensive battle, and in this they were greatly assisted by the nature

of the ground, which was dotted with considerable hummocks, cleft with

ravines and indented with chalk pits and quarries, and was, moreover,

abundantly furnished .with pitheads, mine-works, mills, farms, and the

like, all transformed into miniature fortresses, to approach which was

certain death. They had constructed trenches reinforced by

concrete-lined galleries, and linked them up with underground tunnels.

The battle of the miniature fortresses proved the triumph of the machine

gun. The Germans employed the machine gun to an extent which turned even

a pig-stye into a Sebastopol. Only overwhelming artillery fire could

have shattered this chain of forts, bound by barbed wire and everywhere

covered by machine guns.

Our artillery fire was

not sufficient to reduce them, and the British attack slowly weakened;

and finally the battle died out on the 26th, when Sir John French gave

orders for the curtailment of our artillery fire.

This brings me to the

second reason which has been assigned for our failure to clear the way

to Lille at the battle of Festubert, and that is the debatable one of

“shortage of munitions.”

The military

correspondent of The Times, who had just returned from the front,

affirmed in his journal on May 14th that the first part of the battle of

Festubert had failed through lack of “high explosives.”

The English public was

profoundly disturbed at the failure of an engagement on which it had set

high hopes, and, rightly or wrongly, it fastened on this accusation of

The Times as an indictment of the Government at home. Both the Press and

the public settled down with a grim tenacity to discover what was wrong.

They were alike determined that the British Army in the future should

lack nothing which it required to achieve success.

Amid the hubbub to

which The Times disclosure gave rise, the undercurrent of the reply of

officials at home was never heard, and certainly was never understood.

Probably the answer of Lord Kitchener was this : that the requirements

of those in command in the field, based on the calculations of the

artillery experts there, had been faithfully fulfilled so far as our

resources permitted.

In any case, Festubert

led us to believe that high explosives must determine the issue of

similar battles in the future, and the outcry in England against the

“shortage of munitions” produced the crisis from which emerged the

Coalition Government.

It may therefore be

said that the political effects of Festubert were infinitely greater

than its military results. The munitions crisis cleared the political

atmosphere and gave England a better understanding of the difficulties

of the war and a steadier determination to see it through. It paved the

way for the War Committee, and, finally, for the Allies’ Grand Council

of War in Paris.

I will now proceed to

deal with the battle of Festubert as it concerns the fortunes of the

Canadians. The record is a bald one of work in the trenches by our own

people. It is couched almost in official phrases, but now and then I

have interpolated some personal anecdote which may help to show you what

triumph and terror and tragedy lie behind the smooth, impersonal stage

directions of this war. . .

After the second battle

of Ypres the Canadian Division, worn but not shattered, retired into

billets and rested until May 14th, when the Headquarters moved to the

southern section of the British line in readiness for new operations.

During that time reinforcements had poured in from the Canadian base in

England, where were gathered the Dominion troops, whose numbers we owe

to the large vision and untiring energy of the Minister of Militia and

Defence.

On May 17th the remade

infantry brigades advanced towards the firing line once more.

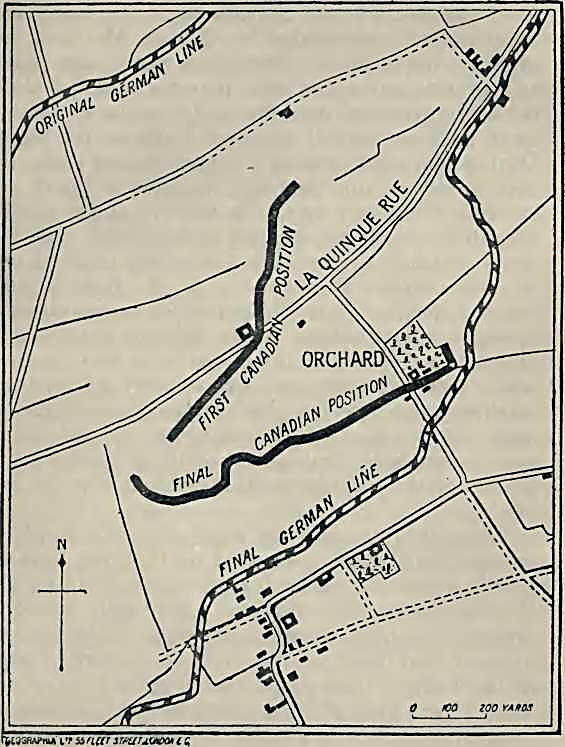

It must be understood

that on the afternoon of May 18th, the 3rd Brigade occupied reserve

trenches, two companies of the 14th (Royal Montreal) Battalion,

commanded by Lieut.-Colonel Meighen, [Lt.-Colonel Meighen led his troops

with capacity and judgment. He had already won distinction at Ypres. In

accordance with the English custom of recalling men who have acquired

experience in the field for training purposes at home, Colonel Meighen

has been sent to Canada, and given charge of the instructional scheme of

the Canadian Forces from the Atlantic to the Pacific, with the temporary

rank of Brigadier-General.] and two companies of the 16th (Canadian

Scottish), under Lieut.-Colonel (now Brig.-General) Leckie, being

ordered to make an immediate advance on La Quinque Rue, north-west of an

Orchard which had been placed in a state of defence by the enemy. One

company of the 16th Canadian Scottish was to make a-flanking movement on

the enemy’s position in the Orchard by way of an old German

communicating trench, and this attack was to be made, of course, in

conjunction with a frontal one.

Little time was

available to make dispositions, and as there was no opportunity to

reconnoitre the ground, it was very difficult to determine the proper

objective. The flanking company of the 16th Battalion reached its

allotted position, but after the advance of the remaining company of

that regiment, and the 14th, under very heavy shell fire, the proper

direction was not maintained. The. detachments reached part of their

objective, but owing to the lack of covering fire it was undesirable at

the moment to make an attack on the Orchard. The companies were told to

dig themselves in and connect up with the Wiltshire Battalion on their

right and the Coldstream Guards on their left. They had then gained 500

yards. Lieut.-Colonel Leckie sent up the other two companies of the 16th

to assist in the digging and to relieve the original two companies at

daybreak. During the night the companies of the 14th Battalion (Royal

Montreal) were also withdrawn, and the trench occupied by these was

taken over by stretching out the Coldstream Guards on one flank and the

16th Canadian Scottish on the other.

[Our men were very

anxious to get to grips with the enemy on this day (May 18th), as it was

the birthday of Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, who had issued an order

that no prisoners were to be taken. Some idea of the efforts made to

incite the enemy’s forces to further outrages against the conventions of

war may be gathered from the following paragraph extracted from the

Lille War News, an official journal issued to the German troops :—

“Comrades, if the enemy were to invade our land, do you think he would

leave one stone upon another of our fathers’ houses, our churches, and

all the works of a thousand years of love and toil? . . . and if your

strong arms did not hold back the English (God damn them I) and the

French (God annihilate them I) do you think they would spare your homes

and your loved ones? What would these pirates from the Isles do to you

if they were to set foot on German soil?”]

On the morning of the

20th orders were issued for an attack on the Orchard that night. A

reconnaissance of the position was made by Major Leckie, brother of

Lieut.-Colonel Leckie, when patrols were sent out, one of which very

neatly managed to escape being cut off by the enemy, and another

suffered a few casualties. This showed the Germans were in force, and

that an attack on the Orchard would be no light work. That night the

Canadian Scottish occupied a deserted house close to the German lines,

and succeeded in establishing there two machine guns and a garrison of

thirty men. The enemy were evidently not aware that we were in

possession of this house, for although they bombarded all the British

trenches with great severity throughout the whole of the next day, this

little garrison was left untouched. The attacking detachment under Major

Rae consisted of two companies of the Canadian Scottish, one commanded

by Captain Morison, the other by Major Peck. The attack was to take

place at 7.45 p.m., and at the same time the 15th Battalion (48th

Highlanders) were directed to make an assault on a position several

hundred yards to the right. During that afternoon the Orchard was very

heavily bombarded by our artillery, the bombardment increasing in

severity up to the delivery of the attack. Promptly to the minute, the

guns ceased, and the two companies of the 16th Canadians climbed out of

their trenches to advance. At the same instant the two machine guns

situated in the advanced post opened on the enemy. As the advance was

carried out in broad daylight, the movements were at once seen by the

Germans, and immediately a torrent of machine gun, rifle fire, and

shrapnel was directed upon our troops. Their steadiness and discipline

were remarkable, and were greatly praised by the officers of the

Coldstream Guards who were on our left.

When they reached the

edge of the Orchard an unexpected obstacle presented itself in the form

of a deep ditch, and on the further side a wired hedge. Without

hesitation, however, the men plunged through the ditch, in some places

up to their necks in water, and made for previously reconnoitred gaps in

the hedge. Not many Germans had stayed in the Orchard during the

bombardment. The bulk of the garrison, according to the usual German

method under artillery fire, had evidently retired to the support

trenches in the rear. A few had been left behind to man a machine gun

redoubt near to the centre of the Orchard with the idea of holding up

our advancing infantry till the enemy, withdrawn during the bombardment,

could return in full strength; but these machine guns retreated when the

Canadians came. On the far side of the Orchard, however, the Germans,

following their system indicated above, came up to contest the position,

but the onset of the Canadians forced them to beat a hasty retreat.

Although double our numbers, they could not be induced to face a

hand-to-hand fight. Three platoons cleared the Orchard, while a fourth

platoon, advancing towards the north side, were hampered by a very

awkward ditch, which forced them to make a wide detour, so that they did

not reach the Orchard until its occupation was complete.

One company did not

enter the Orchard, but pushed forward and occupied an abandoned German

trench running in a south-westerly direction, to prevent any flank

counter-attack being made by the enemy. They then found themselves in a

very exposed position, and consequently suffered heavily. The

casualties, in proportion to the number of men employed in the attack,

were heavy for all engaged, but the position was a very important one,

and had twice repulsed assault by other regiments.

Had our advance been

less rapid the enemy would no doubt have got back into this position,

and our task might have been impossible. They argued, as I have said,

that any attack might be held up by the machine guns in the redoubt and

in the fortified positions on the flank for long enough to enable them

to return to the Orchard after our bombardment had ceased, and then

throw us back. The speed with which our assault was carried out

altogether checkmated this plan.

The 16th Battalion

(Canadian Scottish) included detachments from the 72nd Seaforths of

Vancouver, the 79th Camerons of Winnipeg, the 50th Gordons of Victoria,

and the 91st Highlanders of Hamilton; so all Canada, from Lake Ontario

to the Pacific Ocean, was represented in the Orchard that night.

It was in the course of

the struggle in the Orchard that Sapper Harmon, of the ist Field

Company, C.E., performed one of those exploits which have made Canadian

arms shine-in this war. He was attached to a party of twelve sappers and

fifty infantrymen of the 3rd Canadian Battalion which constructed a

barricade of sandbags across the road leading to the Orchard, in the

face of heavy fire. Later, this barricade was partially demolished by a

shell, and Harmon actually repaired it while under fire from a machine

gun only sixty yards away ! Of the party, in whose company Harmon first

went out, six of the twelve sappers were wounded, and of the fifty

infantrymen six were killed and twenty-four wounded. Later, he remained

in the Orchard alone for thirty-six hours constructing tunnels under a

hedge, with a view to further operations. Sapper B. W. Harmon is a

native of Woodstock, New Brunswick, and a graduate of the University of

New Brunswick.

The drawback to

drill-book tactics is that if one side does not keep the rules the other

suffers. And a citizen army will not keep to the rules. For example, not

long after the affair of the Orchard, a Canadian battalion put up a

little arrangement with the ever-adaptable Canadian artillery in its

rear, The artillery opened heavy fire on a section of German trenches

while the battalion made ostentatious parade of fixing bayonets, rigging

trench ladders and whistling orders, as a prelude to attack the instant

the bombardment should cease. The Germans, who are experts in these

matters, promptly retired to their supporting trenches and left the

storm to rage in front, ready to rush forward the instant it stopped, to

meet the Canadian attack. So far all went perfectly. Our guns were

lifted from the front trenches and shelled the supporting trench, in the

manner laid down by the best authorities, to prevent the Germans coming

up. The Germans none the less came, and crowded into the front trenches.

But there was no infantry attack whatever. That deceitful Canadian

battalion had not moved. Only the guns shortened range once more, and

the full blast of their fire fell on the German front trench, now

satisfactorily crowded with men. Next day’s German wireless announced

that “a desperate attack had been heavily repulsed,” but the general

sense of the enemy was more accurately represented by a “hyphenated”

voice that cried out peevishly next evening: “Say, Sam Slick, no dirty

tricks to-night." But to resume.

At seven o’clock in the

evening of the 20th the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders) of the 3rd

Brigade, under Lieut.-Colonel Loomis, advanced across the British

trenches, under heavy shell fire and with severe losses, in support of

the 16th Battalion Canadian Scottish.

The attack on the

Orchard having succeeded, three companies of the 13th Battalion (Royal

Highlanders) immediately marched forward. As four officers of one

company, including the officer commanding, had been severely wounded,

the command was taken over by Major Buchanan, the second in command of

the regiment.

A fourth company

marched to a support trench immediately in the rear. The position was

then consolidated, and the 16th Battalion, after its hard work and

brilliant triumph, withdrew.

Next afternoon the

enemy in their trenches made a demonstration fifty yards north of the

Orchard, but our heavy fire soon drove them off the parapets. During the

night the disputed ground between the trenches was brightly lighted by

the enemy’s flares and enlivened by the rattle of continuous musketry.

None the less, our working parties went on with their improvements and

left the position in good shape for the 3rd (Toronto) Battalion of the

1st Brigade, which relieved the Royal Highlanders on Saturday.

On the night of May

19th, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade took over some trenches which

had recently been captured by the 21st Brigade (British), and also a.

section of trenches from the 47th Division. The 8th and ioth Battalions

occupied the front-line trenches, the 5th Battalion went into Brigade

Reserve, with one company near Festubert, and three companies bivouacked

in the vicinity of Willow Road; and the 7th Battalion was posted in

Divisional Reserve.

On May 20th, at 7.45

p.m., the 10th Canadian Battalion, under Major Guthrie, who joined the

Battalion at Ypres as a lieutenant after the regiment had lost most of

its officers, made an attempt to secure a position known as “Bexhill.”

This attack was a failure, as no previous reconnaissance had been

carried out, and the preliminary bombardment had been quite ineffectual.

Moreover, our troops were in full view of the enemy when crossing a gap

in the fire trench, and as the only approach to “Bexhill” was through an

old communicating trench swept by machine guns, the leading men of the

front company were all shot down and the 10th Battalion retired. [The

casualties of the 10th Battalion during the fighting in April and May

were 809. The casualties at Ypres alone were 600 of all ranks.]

During the night a

further reconnaissance of the enemy’s position was carried out and

repairs were effected in the gap in the fire trenches, which assured

covered communication to all parts of our line.

On the evening of May

21st an artillery bombardment opened under direction of

Brigadier-General Burstall, and went on intermittently until 8.30, when

our attack was launched. The attacking force consisted of the grenade

company of the ist Canadian Brigade and two companies of the ioth

Canadian Battalion. This attack was met by overwhelming fire from the “

Bexhill ” redoubt, and our force on the left was practically annihilated

by machine guns; indeed, against that steady stream of death no man

could advance. On the right the attackers succeeded in reaching the

enemy’s trench line running south from “ Bexhill,” and, preceded by

bombers, drove the enemy 400 paces down the trench and erected a

barricade to hold what they had won. During the night the enemy made

several attempts to counterattack, but was successfully repulsed. [Coy.

Sergt.-Major G. R. Turner (now Lieutenant), of the 3rd Field Company,

Canadian Engineers, who served with courage and coolness throughout the

second battle of Ypres, and particularly distinguished himself on the

nights of April 22nd and 27th by bringing in wounded under severe

artillery and rifle fire, again attracted the attention of his superior

officers by his courageous conduct at Festubert. From May 18th to 22nd

he was in command of detachments of sappers employed in digging advanced

lines of trenches, and generally constructing defences. This work was

carried through most efficiently, although under fire from field guns,

machine guns, and rifles.]

In our attack, which

was only partially successful, Major E. J. Ashton, of Saskatoon, who was

slightly wounded in the head on the previous night, refused to leave his

command. He was again wounded, and Privates Swan and Walpole tried to

get him back to safety, and in so doing Swan was also wounded. During

the same night Corporal W. R. Brooks, one of the ioth Battalion snipers,

went out from our trench under heavy fire and brought in two men of the

4/7th Camerons who had been lying wounded in the open for three days.

At daybreak of May 22nd

the enemy opened a terrific bombardment on the captured trench, which

continued without ceasing through the whole day and practically wiped

the trench out. [It was during this bombardment that Captain McMeans,

Lieut. Smith-Rewse, and Lieut. Passmore were killed, and Lieut. Denison

was wounded. The fate of Captain McMeans was particularly regrettable as

he had on all occasions borne himself most gallantly. Such was the force

of his example that, when he himself, and all the other officers, as

well as half the men of the Company, had been killed or wounded, the

remainder clung doggedly to the position. The conduct of Captain J. M.

Prower also calls for mention. He was wounded, but returned to his

command as soon as his wounds were dressed, and though again buried

under the parapet, continued to do his duty. He is now Brigade Major of

the 2nd Infantry Brigade. On the same day Coy. Sergt.-Major John Hay

steadied and most ably controlled the men of his Company after all the

officers and 70 men out of the 140 had been put out of action.] After

very heavy casualties the southern end of the captured trench was

abandoned, and a second barricade was erected across the portion that

remained in our hands.

In the afternoon the

enemy’s infantry prepared for an attack, but retired after coming under

our artillery and machine gun fire. During the night the trenches were

taken over by a detachment of British troops and a detachment of the ist

Canadian Infantry Brigade, and by 2nd King Edward’s Horse and

Strathcona’s Horse. These latter served, of course, as infantry, and it

was their first introduction to this war, though Strathcona’s Horse took

part in the South African campaign.

The 2nd King Edward’s

Horse took over the trench held up to that time by the 8th Battalion.

[Casualties of 8th Battalion.—About 90 per cent, of the original

officers and men of the 8th Battalion have been casualties. Only three

of the original officers of the battalion have escaped wounds or death.]

On the right of Strathcona’s Horse were the Post Office Rifles, of the

47th Division; but the Post Office Rifles’ machine guns were manned by

the machine gun detachment of the Strathconas.

May 23rd passed without

incident, although the enemy threatened an attack upon 2nd King Edward’s

Horse, but broke back in the face of a heavy artillery fire searchingly

directed by the Canadian artillery brigades. [This was an attack made by

the 7th Prussian Army Corps which had been very strongly reinforced. The

German efforts to break through the Canadian lines were very determined,

and they advanced in masses, which, however, melted away before our

fire.]

At 11 p.m. on the night

of May 23rd the 5th Canadian Battalion received orders from the General

Officer Commanding the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade to take the

“Bexhill” salient and redoubt, on which our previous attack had failed.

The force detailed for the fresh attack then consisted of two companies

of the Battalion, numbering about 500 men, under Major Edgar, together

with an additional 100 men furnished by the 7th (British Columbia)

Battalion, divided into two parties—fifty to construct bridges before

the attack, and fifty to consolidate whatever positions were gained. The

bridging party was commanded by Lieut, (now Captain) R. Murdie, and he

took his men out at 2.30 a.m. on the morning of May 24th. In bright

moonlight, and under machine gun and rifle fire, he managed to throw

twelve bridges across a ditch 10 ft. in width and full of water, which

lay between our line and the objective of the attack. This party

naturally Suffered heavy casualties. The attack itself went over at

2.45, and in it many of the bridging party joined; at the same time the

battalion bombers under Lieut. Tozer forced their way up a German

communication trench leading to the redoubt. Extremely stiff fighting

followed, but in the face of heavy machine gun fire the redoubt was

occupied shortly after four in the morning. In addition to the redoubt,

the attacking party gained and held 200 yards of trenches to the left of

it, and a short piece to the right, driving the Germans out and back

with heavy losses.

“Bexhill” proper,

however, had still to be taken, and to that end the two companies of the

5th Battalion, which were in reality inadequate to capture so strong a

position, were reinforced by a company from the 7th Battalion and a

squadron of Strathcona’s Horse. [Casualties of 5th Battalion during

Ypres, Festubert, and Givenchy about 60 per cent. Casualties at

Festubert alone, 380, all ranks.] With this reinforcement the attack was

immediately pressed home, and “Bexhill” and 130 yards of trenches

towards the north fell into our hands at 5.49 a.m.

Further progress,

however, was impossible owing to the unbreakable positions of the enemy.

Forty minutes later, at about 6.30 a.m., further reinforcements were

received in the form of a platoon from the 5th Battalion, and with their

arrival came orders to “dig in and hang on,” but not to attempt the

taking of any more ground. It was about this time that Major Odium,

commanding the 7th Battalion, took charge of the 5th, as Colonel Tuxford

was ill and Major Edgar had been wounded soon after the launching of the

attack. The losses among the officers of Major Edgar’s little force had

been terrible. Major Tenaille and Captain Hopkins, who commanded the two

companies, were killed, as were also Captains Maikle, Currie, McGee, and

Mundell, while Major Thornton, Captain S. J. Anderson, Captain Endicott,

Major Morris, Lieut. Quinan, and Lieut. Davis were wounded. Matters were

made worse by the fact that Major Powley was wounded just as he came up

with his reinforcing company from the 7th. All through the morning the

enemy’s artillery was exceedingly active, although the Canadian

artillery surrounded our troops, who were holding on in the redoubt,

with a saving ring of shrapnel, and, at the same time, distracted the

enemy’s guns with accurate fire upon their positions. Canada had good

reason to be proud of her gunners that day.

The captured trenches

were held all day, but only at great cost, by the forces which had won

them; and at night the Royal Canadian Dragoons and the 2nd Battalion of

the 1st Brigade arrived, and took them over.

The total losses of the

2nd Brigade amounted to 55 officers and 980 men.

The hostile shelling

was the most severe that the Brigade ever experienced, but the ordeal

was borne unshakenly.

On the night of May

24th, at 11.30 p.m., while the troops which had taken “Bexhill” were

still hanging on to what they had won, the 3rd Battalion, commanded by

Lieut.-Colonel (now Brigadier-General) Rennie, attacked a machine-gun

redoubt known as “The Well,” which was a very strongly fortified

position. The attacking force gained a section of trench in the position

with fine dash; but to take the redoubt, or to hold their line under the

pounding of bombs and the pitiless fire of the machine guns in the

redoubt, was more than flesh and blood could accomplish. To remain would

have been to die to a man—and win nothing. This heroic attack was

repulsed with heavy losses.

On the following day

(May 25th) at noon, Brigadier-General Seely, M.P., assumed command of

the troops which had won “Bexhill.” General Seely had already endeared

himself to the Canadians by his personality, and now he was to win their

confidence as a leader in the field. He arrived at a perilous and

critical moment, and he at once fastened on the situation with

understanding and vigour. He remained in command until noon on May 27th,

and through two extremely trying and hazardous days and nights,

displayed soldierly qualities and a gift for leadership. Some idea of

the severity of the fighting may be gathered from the fact that the

losses among officers of General Seely’s Brigade included, Lieut. W. G.

Tennant, Strathcona’s Horse, killed; Major D. D. Young, Royal Canadian

Dragoons, Major J. A. Hesketh, Strathcona’s Horse, Lieuts. A. D.

Cameron, D. C. McDonald, J. A. Sparkes, Strathcona’s Horse, Major C.

Harding and Lieuts. C. Brook and R. C. Everett, 2nd King Edward’s Horse,

wounded. The casualties in other ranks, killed, wounded, and missing,

were also very heavy.

An inspiring feature of

the fighting at this particular period was the dash, gallantry, and

steadiness of the regiments of horse which, to relieve the terrible

pressure of the moment, were called on to serve as infantry, without any

fighting experience, and flung into the forefront of a desperate and

bloody battle.

It is impossible to

record all the acts of heroism performed by officers and men, but the

narrative would be incomplete without a few of them.

Major Arthur Cecil

Murray, M.P., of 2nd King Edward’s Horse, for instance, distinguished

himself by the determined and gallant manner in which he led his

squadron, held his ground, and worked at the construction of a parapet

under heavy machine gun fire. The considerable advance made on the left

of the position was in a large measure due to his efforts. Lieut, (now

Captain) J. A. Critchley, of Strathcona’s Horse, armed with bombs, led

his men in the assault on an enemy machine gun redoubt with notable

spirit. Corporal W. Legge, of the Royal Canadian Dragoons, went out on

the night of May 25th and located a German machine gun which had been

causing us heavy losses during the day, and so enabled his regiment to

silence it with converging fire.

It was on May 25th,

too, that Sergeant Morris, of 2nd King Edward’s Horse, accompanied the

Brigade grenade company, who were sent to assist the Post Office Rifles

of the 47th London Division in an attack on a certain position on the

evening of that day.

Morris led the attack

down the German communication trench, and all the members of his party,

with the exception of himself, were either killed or wounded. He got to

a point at the end of the trench and there maintained himself—to use the

cold official phrase—by throwing bombs and by the work of his single

rifle and bayonet. By fighting single-handed he managed to hold out

until the extreme left of the Post Office Rifles came up to his relief.

On the following day,

the 26th, Corporal Pym, Royal Canadian Dragoons, exhibited a

self-sacrifice and contempt for danger which can seldom have been

excelled on any battlefield. Hearing cries for help in English between

the British and German lines, which were only sixty yards apart, he

resolved to go in search of the sufferer. The space between the lines

was swept with incessant rifle and machine gun fire, but Pym crept out

and found the man, who had been wounded in both thigh-bones and had been

lying there for three days and nights. Pym was unable to move him

without causing him pain which he was not in a state to bear. Pym

therefore called back to the trench for help, and Sergeant Hollowell,

Royal Canadian Dragoons, crept out and joined him, but was shot dead

just as he reached Pym and the wounded man.

Pym thereupon crept

back across the fire-swept space to see if he could get a stretcher, but

having regained the trench he came to the conclusion that the ground was

too rough to drag the stretcher across it.

Once more, therefore,

he recrossed the deadly space between the trenches, and at last, with

the utmost difficulty, brought the wounded man in alive.

Those were days of

splendid deeds, and this chapter cannot be closed without recording the

most splendid of all—that of Sergeant Hickey, of the 4th Canadian

Battalion,1 which won for him the recommendation for the Victoria Cross.

Hickey had joined the Battalion at Valcartier from the 36th Peel

Regiment, and on May 24th he volunteered to go out and recover two

trench mortars belonging to the Battalion which had been abandoned in a

ditch the previous day. The excursion promised Hickey certain death, but

he seemed to consider that rather an inducement than a deterrent. After

perilous adventures under hells of fire he found the mortars and brought

them in. But he also found what was of infinitely greater value—the

shortest and safest route by which to bring up men from the reserve

trenches to the firing line. It was a discovery which saved many lives

at a moment when every life was of the greatest value, and time and time

again, at the risk of his own as he went back and forth, he guided party

after party up to the trenches by this route.

[The 4th Canadian

Battalion was under continuous fire at Festubert through ten days and

eleven nights. On the morning of May 27th all communication wires

between the fire-trench and the Battalion and Brigade Headquarters were

cut by enemy fire, and at nine o’clock Pte. (now Lieutenant) W. E. F.

Hart volunteered to mend the wires. Hart was with Major (now

Lieut.-Colonel) M. J. Colquhoun at the time, and they had together twice

been partially buried by shell fire earlier in the morning. Pte. Hart

mended eleven breaks in the wires, and re-established communication with

both Battalion and Brigade Headquarters. He was at work in the Orchard,

under shrapnel, machine-gun, and rifle fire, without any cover, for an

hour and thirty minutes. Hart, who is now signalling officer of the 4th

Battalion, is a young man, and the owner of a farm near Brantford,

Ontario. He has been with the. Battalion since August, 1914.]

Hickey’s devotion to

duty had been remarkable throughout, and at Pilckem Ridge, on April

23rd, he had voluntarily run forward in front of the line to assist five

wounded comrades. How he survived the shell and rifle fire which the

enemy, who had an uninterrupted view of his heroic efforts, did not

scruple to turn upon him, it is impossible to say; but he succeeded in

dressing the wounds of all the five and conveying them back to cover.

Hickey, who was a

cheery and a modest soul, and as brave as any of our brave Canadians,

did not live to receive the honour for which he had been recommended. On

May 30th a stray bullet hit him in the neck and killed him. And so there

went home to the God of Battles a man to whom battle had been joy.

On May 31st the

Canadian Division was withdrawn from the territory it had seized from

the enemy and moved to the extreme south of the British line. Here the

routine of ordinary trench warfare was resumed until the middle of June.

[1 The following is Sir John French’s official reason for bringing the

battle of Festubert to a close:—“I had now reasons to consider that the

battle which was commenced by the ist Army on May 9th and renewed on the

16th, having attained for the moment the immediate object I had in view,

should not be further actively proceeded with. . . .” “In the battle of

Festubert the enemy was driven from a position which was strongly

entrenched and fortified, and ground was won on a front of four miles to

an average depth of 600 yards.”] |