|

Canadians’ valuable

help—A ride in the dark—Pictures on the road—Towards the enemy—At the

cross-roads—“Six kilometres to Neuve Chapelle”—Terrific bombardment—

Grandmotherly howitzers—British aeroplanes—Fight with a Taube—Flying

man’s coolness—Attack on the village— German prisoners—A banker from

Frankfort—The Indians’ pride—A halt to our hopes—Object of Neuve

Chapelle—What we achieved—German defences underrated—Machine gun

citadels—Great infantry attack— Unfortunate delays—Sir John French’s

comments—British attack exhausted—Failure to capture Aubers Ridge—

“Digging in”—Canadian Division’s baptism of fire—

“Casualties’’-Trenches

on Ypres salient.

“The glory dies not, and the grief is past.”—Brydges.

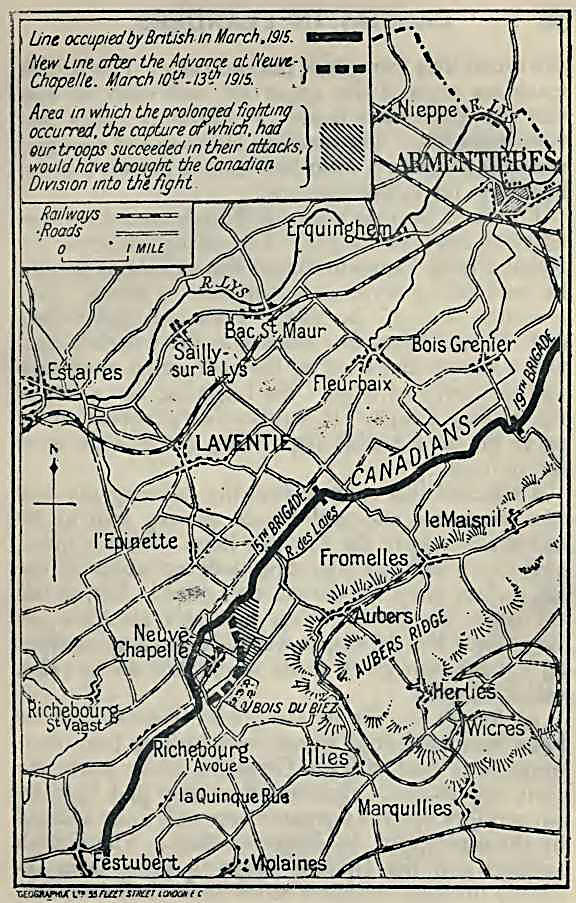

“During the battle of

Neuve Chapelle the Canadians held a part of the line allotted to the

First Army, and, although they were not actually engaged in the main

attack, they rendered valuable help by keeping the enemy actively

employed in front of their trenches.”—Sir John French's Despatch on the

Battle of Neuve Chapelle, which began on March 10th, 1915.

It was night when I

left the Candian Divisional Headquarters and motored in a southerly

direction towards Neuve Chapelle. It was the eve of the great attack,

and in the bright space of light cast by the motor lamps along the road,

there came a kaleidoscopic picture of tramping men.

Here at the front there

is no need of police restrictions on motor headlights at night as there

is in London and on English country roads. The law under which you place

yourself is the range of the enemy’s guns. Beyond that limit you are

free to turn your headlights on, and there is no danger. But, once

within the range of rifle fire or shell, you turn your lights on at the

peril of your own life. So you go in darkness.

As we rode along with

lamps lit, thousands of khaki-clad men were marching along that road—

marching steadily in the direction of Neuve Chapelle. The endless stream

of their faces flashed along the edge of the pave in the light of our

lamps. Their ranked figures, dim one moment in the darkness, sprang for

an instant into clear outline as the light silhouetted them against the

background of the night. Then they passed out of the light again and

became once more a legion of shadows, marching towards dawn and Neuve

Chapelle. The tramp of battalion after battalion was not, however, the

tramp of a shadow army, but the firm, relentless, indomitable step of

armed and trained men.

Every now and then

there came a cry of “Halt,” and the columns came on the instant to a

stand. Minutes passed, and the command for the advance rang out. The

columns moved again. So it went on—halt—march—halt—march—hour by hour

through the night along that congested road—a river of men and guns.

For while in one

direction men were marching, in the other direction came batteries of

guns, bound by another route for their position in front of Neuve

Chapelle. The two streams passed one another— legions of men and

rumbling, clattering lines of artillery, all moving under screen of the

dark, towards the line of trenches where the enemy lay.

This was no time to

risk a block in traffic, and my motor, swerving off the paved centre of

the road, sank to her axles in the quagmire of thick, sticky mud at the

side. The guns passed, and we sought to regain the paved way again, but

our wheels spun round, merely churning dirt. We could not move out of

that pasty Flemish mud, until a Canadian ambulance wagon came to our

aid. The unhitched horses were made fast to the motor, and they heaved

the car out of her clinging bed.

In the early morning I

came to the cross roads. The signpost planted at the crossing and

pointing down the road to the south-east bore the inscription “Six

kilometres to Neuve Chapelle.”

This was the road that

the legions had taken. It led almost in a straight line to the trenches

that were to be stormed, to the village behind them that was to be

captured, and to the town of La Bassee, a few kilometres further on,

strongly held by the Germans.

“Six kilometres to

Neuve Chapelle”—barely four miles; one hour’s easy walking, let us say,

on such a clear, fresh morning; or five minutes in a touring car if the

time had been peace. But who knew how many hours of bloody struggle

would now be needed to cover that short level stretch of “Six kilometres

to Neuve Chapelle”! Between this signpost and the village towards which

it pointed the way, many thousands of armed men—sons of the Empire— had

come from Britain, from India, from all parts of the Dominions Overseas,

to take their share in driving the wedge down to the end of this six

kilometres of country road, and through the heart of the German lines.

Here for a moment they paused. What hopes, what fears, what joys, what

sorrows, triumphs and tragedies were suggested by that austere signpost,

pointing “like Death’s lean-lifted forefinger” down that little stretch

of road marked “Six kilometres to Neuve Chapelle”!

I went on foot part of

the way here, for so many battalions of men were massed that motor

traffic was impossible. These were troops held in reserve. Those

selected for the initial infantry attack were already in the trenches

ahead right and left of the further end of the road, waiting on the

moment of the advance.

I had just passed the

signpost when the comparative peace of morning was awfully shattered by

the united roar and crash of hundreds of guns.

This broke out

precisely at half-past seven. The exact moment had been fixed beforehand

for the beginning of a cannonade more concentrated and more terrific

than any previous cannonade in the history of the world. It continued

with extraordinary violence for half-an-hour, all calibres of guns

taking part in it. Some of the grandmotherly British howitzers hurled

their enormously destructive shells into the German lines, on which a

hurricane of shrapnel was descending from a host of smaller guns. The

German guns and trenches offered little or no reply, for the enemy were

cowering for shelter from that storm.

I turned towards the

left and watched for awhile the good part which the Canadian Artillery

played in that attack. The Canadian Division, which was a little further

north than Neuve Chapelle, waited in its trenches, hoping always for the

order to advance.

Then I passed down the

road until I came to a minor crossways where a famous general stood in

the midst of his Staff. Motor despatch riders dashed up the road,

bringing him news of the progress of the bombardment. The news was good.

The General awaited the moment when the cannonade should cease, as

suddenly as it had begun, and he should unleash his troops.

Indian infantry marched

down the road and saluted the General as they passed. He returned the

salute and cried to the officer at the head of the column, “Good luck.”

The officer was an Indian, who, with a smile, replied in true Oriental

fashion: “Our Division has doubled in strength, General-Sahib, since it

has seen you.”

While the bombardment

continued, British aeroplanes sailed overhead and crossed over to the

German lines. The Germans promptly turned some guns on them. We saw

white ball-puffs of smoke as the shrapnel shells burst in front, behind,

above, below, and everywhere around the machines, but never near enough

to hit. They hovered like eagles above the din of the battle, surveying

and reckoning the damage which our guns inflicted, and reporting

progress.

Once a German Taube

rose in the air and lunged towards the British lines. Then began a

struggle for the mastery, which goes to the machine which can mount

highest and fire down upon its enemy. The Taube ringed upwards. A couple

of British aeroplanes circled after it. To and fro and round and round

they went, until the end came. The British machines secured the upper

air, and soon we saw that the Taube was done. Probably the pilot had

been wounded. The machine drooped and swooped uneasily till, like a

wounded bird, it streaked down headlong far in the distance.

I walked over to where

a British aeroplane was about to start on a flight. The young officer of

the Royal Flying Corps in charge was as cool as though he were taking a

run in a motor-car at home. “ As a matter of fact,” he said, “ I wanted

change and rest. I had spent five months in the trenches, and was worn

out and tired by the everlasting monotony and drudgery of it all. So I

applied for a job in the Flying Corps. It soothes one’s nerves to be up

in the air for a bit after living down in the mud for so long.”

I watched him soar up

into the morning sky and saw numerous shrapnel bursts chasing him as he

sailed about over the German lines. What a quiet, easy-going holiday was

this, dodging about - in the air, a clear mark for the enemy’s guns !

But, to tell the truth, the British flying men and machines are very

rarely hit. Flying in war-time is not so perilous as it looks, though it

needs much skill and a calm, collected spirit.

At length the din of

the gunfire ceased, and we knew that the British troops were rushing

from their trenches to deal with the Germans, whose nerve the guns had

shaken. Astounded as they had been by our artillery fire, the Germans

were still more amazed by the rapidity of the infantry attack. The

British soldiers and the Indians swept in upon them instantly till large

numbers threw down their weapons, scrambled out of their trenches, and

knelt, hands up, in token of surrender.

The fight swept on far

beyond the German trenches, through the village, and beyond that again.

The big guns occasionally joined in, and the chatter of the machine-guns

rose and broke off. Now the motor ambulances began to come back—up that

road down which the finger pointed to Neuve Chapelle. They lurched past

us as we stood by the signpost in an intermittent stream, bearing the

wounded men from the fight.

Presently the cheerful

sight of German prisoners alternated with the saddening procession of

ambulances. Large squads of prisoners went by, many hatless and with

dirt-smeared faces, their uniforms looking as though dipped in mustard,

the effect of the bursting of the British lyddite shells among them in

their trenches. The dejection of defeat was on their faces.

Some of them were

halted and were questioned by the General. One man turned out to be a

Frankfort banker, whose chief concern later was what would become of his

money, which he said had been taken charge of by some of his captors. He

was also anxious to know where he would be imprisoned, and seemed

relieved, if not delighted, when he heard that it would be in England.

Another prisoner had

been a hairdresser in Dresden. The General questioned him, and he gave

an entertaining account of his experiences as a soldier.

“I am a Landwehr man,”

he said. “I was in Germany when I was ordered to entrain. Presently the

train drew up and I was ordered to get out, and was told I had to go and

attack a place called Neuve Chapelle. So I went on with others, and soon

we came into a hell of fire, and we ran onwards and got into a trench,

and there the hell was worse than ever. We began to fire our rifles.

Suddenly I heard shouting behind me, and looked round and saw a large

number of Indians between me and the rest of the German Army. I then

looked at the other German soldiers in the trench and saw that they were

throwing their rifles out of the trench. Well, I am a good German, but I

did not want to be peculiar, so I threw my rifle out also, and then I

was taken prisoner and brought here. Although I have not been long at

the war, I have had enough of it. I never saw daylight in the

battlefield until I was a prisoner.

Some of the prisoners

were brought along by the Indian troops who had captured them. They

complained bitterly that they, Germans, should be marched about in the

custody of Indians! They did not understand the grimly humorous reply :

“ If the Indians are good enough to take you, they are good enough to

keep you.55

The Indians smiled with

delight, for they are particularly fond of making prisoners of Germans.

Most of them brought back their little trophies of the fight, which they

held out for inspection with a smile, crying, “Souvenir!"

The stream of prisoners

and of wounded passed on. The fury of battle relaxed. Now and then some

of the guns still crashed, but the machine guns rattled further and

further away, and the crackle of the rifle fire came from a distance.

The British Army had

traversed in triumph those “six kilometres to Neuve Chapelle.”

At Neuve Chapelle it

halted, and there halted, too, the hopes of an early and conclusive

victory for the Allied forces.

The enemy’s outposts

had been driven in, but beyond these, their fortified places bristled

with machine guns, which wrought havoc on our troops, and, indeed,

brought the successful offensive to a close. Controversy has arisen over

the disappointing results which were achieved. For a month after the

battle, Neuve Chapelle was heralded by the public as a great British

victory. But doubt followed confidence, and in a few weeks the “victory”

was described as a failure. The truth lies between these extremes.

The object of this

battle of Neuve Chapelle was to give our men a new spirit of offensive

and to test the British fighting machine which had been built up with so

much difficulty on the Western front. Besides, if this attack succeeded

in destroying the German lines, it would be possible to gain the Aubers

ridge which dominates Lille. That ridge once firmly held in our hands,

the city should have been ours. That would have been a great victory. It

would probably have meant the end of the German occupation of this part

of France. In any case it must have had a marked effect upon the whole

progress of the war.

That was what we hoped

to do. What we actually accomplished was the winning of about a mile of

territory along a three-mile front, and the straightening of our line.

The price was too high for the result.

It was the first great

effort ever made by the British to pierce the German line since it had

been established after the open field battles of the Marne and the

Aisne. The British troops had faced the German lines for months, and

while the fundamental principles of the German defences were fairly well

understood, their real strength was very much underrated.

Things went badly from

the beginning of the action. The artillery “preparation” represented

quite the most formidable bombardment the British had so far made, but

even so, it was ineffective along certain sections of the line. After

the way had been paved by shrapnel and high explosive, the British

infantry moved forward in a splendid offensive to secure what everyone

believed would be a decisive victory; and trained observers of the

battle were under the impression that the gallant British infantry had

won their end. This is an impression, too, which was shared by some of

the men for a time.

For many months the

British had been almost entirely on the defensive, and over and over

again had been called on to repulse heavy, massed German attacks. The

casualties sustained in repulsing

prevent his massing

reinforcements to meet the main attack, two other supplementary attacks

were also to be made—one attack by the ist Corps from Givenchy, and the

other by the 3rd Corps— detailed from the 2nd Army for that purpose—to

the south of Armentieres.

these attacks first

revealed our shortage of machine-guns. What they lacked in machine-guns,

however, the British troops made up for in a deadly accuracy of rifle

fire, which was at once the terror and the admiration of the Germans.

The British had thus come to an exaggerated idea of the efficacy of

rifle fire, and a consequent over-estimate of the importance of the

German first line trenches. Over these they swarmed, and the word went

forth that the day was won.

It was only when the

British troops had occupied the enemy’s first and second line trenches,

they discovered that, in actual fact, they had not done more than drive

in the outposts of an army. Close at hand, the Germans’ third line

loomed up like a succession of closely interlocked citadels. Nay, more,

those citadels were so constructed that the trenches from which our men

had ousted the enemy with so much heroism and loss were deathtraps for

the new tenants. The circumstances were such that to retire meant

acknowledgment of failure, and to hang on, a grisly slaughter.

Even so, there were

features of the situation which made for hope. There were positions to

be won which would very seriously jeopardise the whole German scheme of

defence; but, at the critical moment of the battle, the advanced troops

seem to have passed beyond the control of the various commanders in the

rear on account of the misty weather.

The real tragedy,

however, was the non-arrival of the supports at a point and at a time

when the appearance of reserves might have made all the difference to

the fortunes of the day. The enemy was still bewildered and demoralised,

and, but for the delay, might have been completely routed.

Unfortunately, the British front was in great need of straightening out.

The 23rd Brigade continued to hang up the 8th Division, while the 25th

Brigade was fighting along a portion of the front where it was not

supposed to be at all. Units had to be disentangled and the whole line

straightened before further advance could be made.

The fatal result was a

delay which, Sir John French says, would never have occurred had the

“clearly expressed orders of the General Officer commanding the 1st Army

been more carefully observed.”

Sir Douglas Haig

himself hurried up to set things right, but it was then too late to

retrieve the failure which had been occasioned by delay. The attack was

thoroughly exhausted, its sting was gone, and the enemy had pulled

himself together. Night was falling, and there was nothing to be done

but “dig in” beneath the ridge above Lille, the capture of which would

have altered the whole story of the campaign on the Western front.

As I have said, the

Canadian infantry took no part in the battle, though the troops waited

impatiently and expectantly for the order to advance, but the activity

of the Canadian artillery was considerable and important. The Canadian

guns took their full share in the “preparation” for the subsequent

British infantry attack, and the observation work of our gunners was

good and continuous.

After Neuve Chapelle,

quiet reigned along the Canadian trenches, though the battle raged to

the north of us at St. Eloi, and the Princess Patricia’s Battalion was

involved. Early in the last days of March our troops were withdrawn and

retired to rest camps.

The Canadians had

received their baptism of fire, and in extremely favourable

circumstances. They had not been called on to make any desperate attacks

on the German lines. Nor had the Germans launched any violent assaults

upon theirs. The infantry had sustained a few casualties, but that was

all; while German artillery practice against our trenches had been

curtailed on account of the violent fighting both to the south and the

north.

On the other hand, we

had been surrounded by all the circumstances of great battles. We had

watched the passage of the giant guns, of which the British made use for

the first time at Neuve Chapelle, and we had moved and lived and stood

to arms amid all the stir and accessories of vehement war. The guns had

boomed their deadly message in our ears, we had seen death in many

forms, and understood to the full the meaning of “Casualties" while, day

by day, the aeroplanes wheeled and circled overhead, passing and

re-passing to the enemy’s lines.

The Canadians had come

to make war, and had dwelt in the midst of it, and after their turn in

the trenches many of them, no doubt, accounted themselves war-worn

veterans. Little they knew of the ordeals of the future. Little they

dreamt, when towards the middle of the month of April they were sent to

take over French trenches in the Ypres salient, that they were within a

week of that terrible but wonderful battle which has consecrated this

little corner of Flanders for Canadian generations yet unborn. |